The Patterns Behind Book Bannings Throughout History

As long as books have existed, certain books have riled the public for some reason or another. Such books have been contested, disputed, denounced, repudiated, outright banned, and sometimes even burned. Some texts have been ignominiously bowdlerized — certain passages rewritten or removed for censorship purposes — a word coined in reference to 19th-century editor Thomas Bowdler who took it upon himself to rewrite whole passages of Shakespeare in order to remove "indelicate or offensive passages." In other words, Bowdler was offended by Shakespeare's often bawdy, sexual humor and supposedly indecorous references to body parts. Such changes help explain the reasons why some books tend to draw ire, as well as the motivations behind many book bannings.

Often a book is banned simply because of the subject matter. Sexual, racial, religious, political, and violent content tends to provoke people and pull attention away from the artistry or purpose of a work. As sites like The Guardian describe, advocates or activists might even count the number of specific, objectional words contained in a book, like Mark Twain's 1885, period-accurate "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn." Sometimes, challenges to books seem reasonable. Other times they seem ludicrous. But in all cases, book bannings ironically raise the profile of a book and make people more interested in it. And within the past couple of years, NPR reports that the number of book bannings in the U.S. has skyrocketed, and even includes beloved authors like Toni Morrison and Roald Dahl.

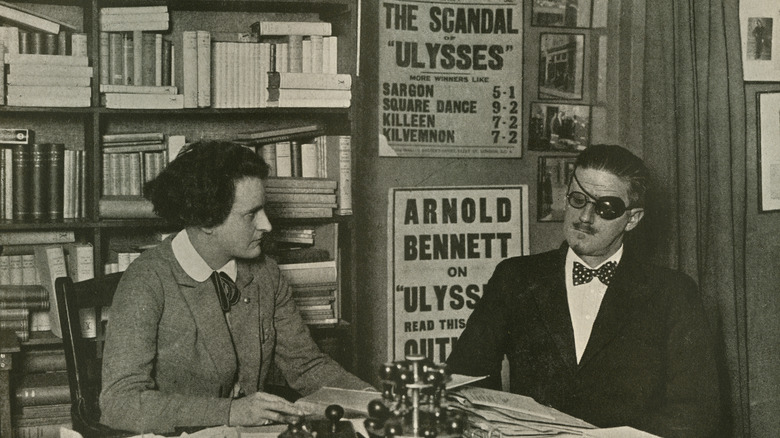

Obscenity case study: Ulysses

1922's "Ulysses" by Irish author James Joyce provides a good historical example of one big reason books get challenged: perceived obscenity. "Ulysses," a reimagining of the Greek epic poem "The Odyssey," is widely regarded as an unparalleled 20th-century masterpiece. Like some of Joyce's other works — "Finnegan's Wake" in particular — it's full of obscure, sometimes difficult-to-understand passages. But in the case of "Ulysses," such passages, and Joyce's overall authorial prowess, formed a critical legal precedent that protected later books facing challenges from the public: the value of artistic merit.

As The Conversation discusses, "Ulysses" is a book that very much inhabits its characters' bodies and focuses on their physical lives. It's also a book that many at the time considered profane, obscene, and even pornographic. Passages include a man on a beach masturbating while staring at a 17-year-old, graphic sex acts between a man and sex worker, and a woman thinking about how much she loves rough sex. Supporters like the poet Ezra Pound said that realistic portrayals were needed for a book to represent the real world.

"Ulysses" eventually went to court, and in 1933's "The United States vs. One Book Called Ulysses" Judge John M. Woolsey deemed that copies of "Ulysses" should not be destroyed because the book held great literary value. When reading the book the judge didn't detect "the leer of the sensualist," and believed that Joyce was undertaking "a serious experiment in a new, if not wholly novel, literary genre."

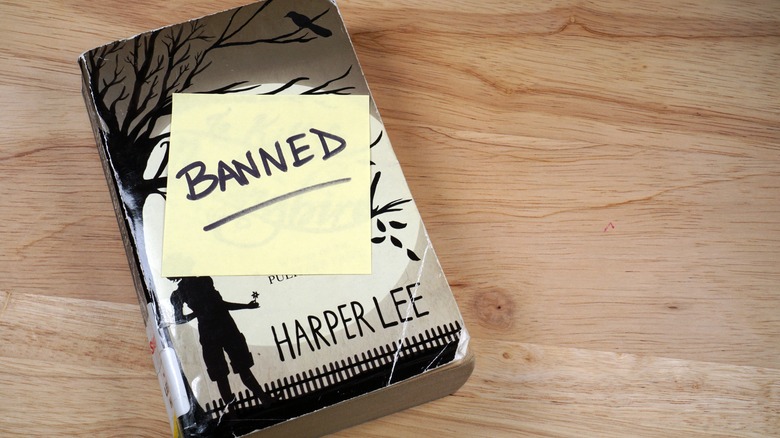

Racism case study: To Kill a Mockingbird

1960's much-adored "To Kill a Mockingbird" has been continually challenged and banned over the course of its existence for a reason still very familiar to folks nowadays: perceived racism. It's been banned despite selling 40 million copies worldwide since its release, winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1961, and topping PBS' reader-voted The Great American Read list of top 100 American books. In fact, "To Kill a Mockingbird" illustrates a key point about book bannings: if a book is well-known and passes more eyes, it's more likely to upset someone somewhere. This is especially true if the book gets assigned in school.

Harper Lee's novel, as readers might know, centers on the story of lawyer Atticus Finch defending a man in court, Tom Robinson, who is accused of rape. Set in the American South, the book very directly tackles the issue of race by making the lawyer white and the defendant Black, and the story itself is about people receiving fair treatment under the law. Ironically, and arguably absurdly, the book still gets called out for racism. CrossCut explains that some claim it portrays a "white savior" narrative and that students shouldn't have to "endure embarrassing and offensive language" in classrooms. The Banned Books Project discusses several specific conflicts regarding the book, even as recently as 2017 and 2018. "To Kill a Mockingbird" has been variously removed from curriculums, kept in circulation, had its text bowdlerized, or required parental permission to read.

Blasphemy case study: The Satanic Verses

If any text provides a perfect example of how religious issues can cause a book to get banned, it's Salman Rushdie's "The Satanic Verses." As The Guardian describes, Rushdie suspected his book might cause a bit of a stir in Muslim-majority countries, but he couldn't have predicted causing such an absolute deluge of outrage. Like many of the author's novels, "The Satanic Verses" published in 1988, is a story about immigration told like a magical fable, in this case featuring two men who fall from an airplane crash. One becomes the angel Gabriel, the other becomes the devil. The book also features a retelling of the prophet Muhammad's early days when founding Islam.

"The Satanic Verses" caused literal riots around the world in places like Kashmir and Srinagar. Muslim-majority countries banned it one after the other. Rushdie hired a bodyguard amidst death threats and canceled trips. On February 14, 1989, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini declared a fatwa on Rushdie, demanding his holy execution and the deaths of anyone involved in the book's publishing. As The Evening Standard explains, Rushdie had to go into hiding for almost a decade. Even as recently as 2022 — 33 years after the fatwa was issued — Rushdie was attacked by 24-year-old Hadi Matar while speaking on stage. The author was stabbed, lost an eye, and nearly lost the use of one hand, as the BBC explains. He's currently undergoing therapy and recovering bit by bit, both physically and psychologically.

Violence case study: The Color Purple

Like the other books that this articles cites, 1982's "The Color Purple" by Alice Walker represents just one instance of a commonly cited reason for book banning — violence. "The Color Purple" has the distinction of being banned not only for violence in general, but violence against women and violence amongst the Black community, which ties into gender and race issues. It also contains homosexuality between women, which is an entire issue unto itself. Like "To Kill a Mockingbird," "The Color Purple" won the Pulitzer Prize, this time in 1983. And like "To Kill a Mockingbird," "The Color Purple" won further fame — and scrutiny — through a movie adaptation.

As The Banned Books Project explains, "The Color Purple" has been challenged relentlessly since being published, and banned from library after library. The Washington Post cites Jackson County, North Carolina board member Bernard King as saying, "It could lead to different sex games and violence and other things." LitCharts describes numerous scenes likely to give parents pause if the book is assigned in school: a Black character beaten by white police, spousal abuse, attempted rape, lynchings, and Olinka tribespeople in Africa murdered en masse by a white land owner. Much like other banned books, Walker uses necessary evils to teach and explain greater themes — in this case the cyclical nature of suffering. But as usual, objectors focus almost exclusively on the presence of subject matter alone.

Age inappropriate case study: children's books

We round out our list of book banning patterns by looking at children's literature in general. As the reader could imagine, any of the aforementioned reasons that adult books get banned can factor in to why a children's book is banned. All in all, banning children's books boil to one notion: age-inappropriate material. Parents can debate eternally over what age is what information suitable for what child, but in the end books designed for children make easy targets no matter what.

In many cases, children's literature is challenged because it appears to encourage defiance against authority figures, which speaks much more about the fears of authority figures than anything. As Tiny Beans explains, Dr. Seuss' "Hop on Pop" provides an example of such an objection, as well as Shel Silverstein's "Where the Sidewalk Ends." Similarly, Marshall Libraries tells us that books in the "Captain Underpants" series have been banned for "encouraging disruptive behavior," amongst other things.

Per Tiny Beans, other examples of banned children's books include "Where the Wild Things Are" and "Hansel and Gretel" because of "dark" content. "Charlotte's Web" has been challenged because some believe that talking animals are religiously offensive. "Harriet the Spy" has been banned because it teaches kids to "lie, spy, talk back and curse." "A Wrinkle in Time" and "The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe" have been challenged for mystical, occult content. On and on it goes, and on it on it's likely to go.