Operation Mincemeat: How The Allies Tricked Germany With A Dead Body

Desperate times call for desperate measures, the saying goes — and recent history has seen few times as desperate as the long, dark days of World War II. By 1942, the Allies were finally in a position where they could consider delivering a well-placed thrust into German-held territory, but there was a massive "but" when it came time to talk targets on the way to gaining a foothold into Italy.

It was Winston Churchill who succinctly summed up the problem (via the BBC): "Everyone but a bloody fool would know that it's Sicily." And it pretty much had to be Sicily, so the Allies knew that they had one weird choice: Make Germany believe that they weren't going after the obvious target.

And that's when Operation Mincemeat was hatched, and the entire thing is just as bizarre as the name suggests. It's unlikely, audacious, and the sort of thing that seems like it would only work in a spy movie, but it didn't just work, it worked perfectly. And then, it was all but forgotten about for a long time. Although there was a book written about it — "The Man Who Never Was" — that was served up with a healthy helping of propaganda and redaction. It wasn't until historian and author Ben Macintyre started doing some serious digging that he discovered that Jeremy Montagu — the son of one of the masterminds behind the plan — still had all his father's once-classified documents. And they told a whopper of a tale.

The Trout Memo and James Bond

One of the strangest pieces of prep work that was done in the first days of the war was something that came to be known as the Trout Memo, and it likened the idea of misdirection and counterintelligence to the idea of fly fishing. The memo was, in theory, sent from the British director of naval intelligence, a man named Admiral John Godfrey. Only, like many higher-ups, he seems to have outsourced the actual work to one of his assistants, and as Ben Macintyre says in his book, "Operation Mincemeat," it's not entirely surprising that the assistant was one Ian Fleming. And yes, that Ian Fleming, of James Bond fame.

The memo included 51 suggestions for "introducing ideas into the heads of the Germans," and it was some bizarre stuff. No one idea was perhaps more bizarre than the one they went with, as Fleming had written for one suggestion: "... a corpse dressed as an airman, with despatches in his pockets, could be dropped on the coast, supposedly from a parachute that had failed."

It sounds like the stuff of fiction, and that's a good reason for that: Fleming actually gave a hat tip to the author he'd gotten the idea from. Basil Thomson was a former WWI spy hunter turned writer, who used the idea of falsified documents planted on a dead man in his 1937 book "The Milliner's Hat Mystery." Thomson never lived to see his idea become reality — he died in 1939.

The Allies turned to an unlikely duo

British intelligence absolutely knew how far outside the box the ideas were, with Admiral John Godfrey writing, "World War II offers us far more interesting, amusing, and subtle examples of intelligence work than any writer of spy stories can devise." Still, they needed agents capable of the right kind of mental gymnastics needed to make the wild idea into reality, and for that, British intelligence turned to two men.

"Operation Mincemeat" says that Charles Cholmondeley was uniquely suited to the task, capable of what was referred to as "corkscrew thinking." He had washed out of his dreams of becoming a pilot — poor eyesight kept the RAF intelligence officer at a desk — and he'd been assigned to an ultra-classified XX (Twenty) Committee tasked with overseeing Allied double agents and coming up with off-the-wall ideas for subterfuge. It was Cholmondeley who framed Fleming's plan to deliver falsified documents to German hands via a corpse as a serious idea, and surprisingly, it wasn't the worst thing they'd heard.

Recruited to help him put the plan into action was the fantastically wealthy Ewen Montagu. (He'd been born into a banking dynasty, and grew up in the sort of house that had somewhere around 20 servants at any given time.) A lawyer by trade, he was recruited by Godfrey, promoted through the ranks of Naval Intelligence, and given his own department: 17M.

They needed a body ... but not just any body

Operation Mincemeat seemed incredibly straightforward: Find a corpse, plant some documents on it confirming that the Allies were going to invade somewhere that definitely wasn't Sicily, then drop the body somewhere it would be discovered by the right people. But once the team led by Ewen Montagu and Charles Cholmondeley started working, it ended up being surprisingly complicated.

Historian and author Ben Macintyre explained to NPR that although they'd thought finding a body in the middle of one of the bloodiest wars in history was going to be easy, it wasn't. "The body had to look as if it had died in an air crash. That was the center of the ruse. The body would be floated ashore at a particular point, wearing a life jacket, but it had to look as if it had died at sea."

The Los Angeles Times says that the Operation Mincemeat team ended up pushing the boundaries of legalities in obtaining the body they needed. After reaching out to a London coroner with the unlikely name of Bentley Purchase, they found their body. The remains of a Welsh man named Glyndwr Michael had been found in a London warehouse, and although the official report claimed that he had died by suicide, Macintyre believes (via the BBC) that he was so desperately hungry he had eaten bread laced with rat poison. Either way, he passed into the hands of Naval Intelligence, who put him on ice while they crafted their ruse.

Baiting the hook

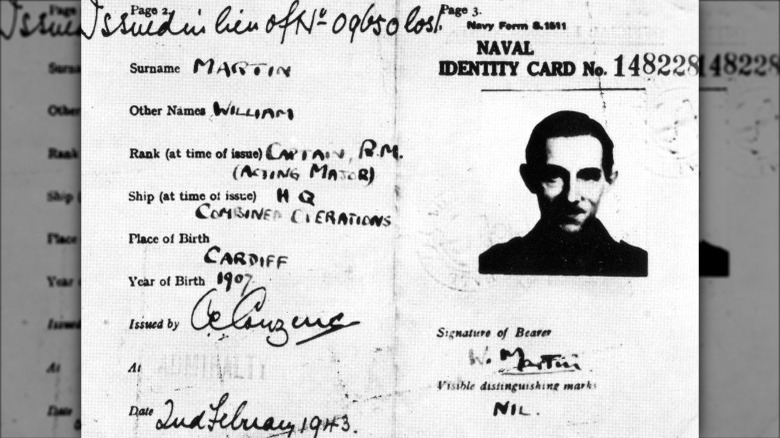

It wasn't going to be good enough to put a life jacket on the dead man and chuck him into the water, and the Operation Mincemeat team spent a shocking amount of time and effort crafting the Welsh man's new identity. That was Captain (Acting Major) William Martin of the Royal Marines, and they pulled out all the stops. Historian Ben Macintyre spoke to the BBC about his research, and was shocked at the effort put in.

Along with the fake top-secret documents, the body was also carrying the sort of debris one might expect to find a person carrying: receipts, some keys, cigarettes, and matches. He was also carrying letters, including one that was supposedly sent by his father, mailed from a hotel. Macintyre went to the hotel, found the register on the day the letter was supposedly mailed, and there was a Mr. Martin, signed in on the day in question.

The kind of detail needed to convince the notoriously thorough Germans took a while, and Glyndwr Michael sat on ice for months while the agents crafted his backstory. According to Macintyre, the thing that made "William Martin" real and entirely believable was his fiancée, Pam. Pam, he wrote in "Operation Mincemeat," was an amalgamation of several of the department's female employees. The photo "Martin" carried (pictured) was actually of secretary Jean Leslie, and the love letters that were folded up with the photo were written by another secretary, Hester Leggett. Add in a disapproving father and a whirlwind, wartime romance, and William Martin was ready to go ... almost.

Looking to a real-life Q for help

Glyndwr Michael/William Martin may have been ready to go, but the Operation Mincemeat team ran into another huge problem: How to get the body to the right offshore location without being seen, and without destroying the body. According to Ben Macintyre's "Operation Mincemeat," most of the solutions that were pitched were too risky, too complicated, or just didn't seem plausible. The option deemed to be the best — using a submarine — had problems, too, starting with the fact that chugging along with a rotting corpse on board was the sort of thing that a crew was likely to protest.

Enter Charles Fraser-Smith, the British Secret Service man who spent the war years with an official title and position on the Ministry of Supply's Clothing and Textile Unit, while really holding an unofficial, top-secret position as an inventor and supplier of gadgets. Sound familiar? It should, because he worked closely with Ian Fleming and is believed to have been the very real inspiration for the not-so-fictional-after-all Q.

In addition to a slew of inventions that included things like shoelaces that concealed a steel garrote, he came up with a torpedo-like canister for transporting the unfortunate corpse. Air was removed, dry ice was used to keep the body in the right state of freshness, and as it was labeled "Optical Instruments," it was unlikely to cause a fuss. The canister — which did, in fact, fit into a torpedo hatch — was built, a reliable submarine captain was found, and it was go-time.

Drop-off ... and the pick-up

Finally, the body of the so-called William Martin was set adrift off the coast of Spain. It was no overnight trip: According to the BBC, it took the HMS Seraph (pictured are the sub's officers) 10 days to deliver their strange cargo, and along the way, they were attacked twice. Once they were in position, the body was released. Then, on April 30, 1943, "William Martin" was found.

As bizarre as the entire plan was, there was nothing that was done accidentally. The body was released off the coast of Huelva, Spain, a medium-sized city that The National WWII Museum says had a few important things: A German consulate, a British Consul named Francis Haselden, and several people associated with the Abwehr.

All of those pieces ended up being invaluable. The British Consul was able to fast-track the autopsy and the funeral, ensuring that there was minimal investigation into the state of the body before it was buried on May 2. Then, another epic bit of subterfuge. The briefcase that had been attached to the corpse was recovered by the Spanish military, who absolutely let Germany know they'd recovered what seemed to be a top-secret message carried by an ill-fated courier. Meanwhile, those in-the-know in London sent a series of increasingly concerned messages to Haselden stressing the importance of the documents and letting him know that they needed to be recovered. Counting on the Germans intercepting the messages about the important documents, they used a code that they knew had already been broken.

The misinformation settled an Axis debate

When the Spanish finally returned the briefcase, British agents confirmed that yes, the documents had been opened and read. What, exactly, did they read? According to The New Yorker, the letter in the briefcase was apparently destined for the desk of General Harold Alexander, who was serving alongside Eisenhower in Tunisia. It outlined everything: The Allies were going to use their foothold in North Africa to attack German-occupied areas of Greece and, in particular, Sardinia.

One of the reasons the plan worked was that it supplied an answer to a question the Germans had been mulling over for some time. They knew the Allied armies were going to use North Africa as a jumping-off point, that was just a given. And Sardinia was one of the logical choices for them to land, particularly because it was a hard place to defend. And while some — including Benito Mussolini and many of the German higher-ups — thought that Sicily was the likelier target for an invasion, Sardinia had supporters in the German Army, too. In fact, Adolf Hitler himself thought Greece was higher on the Allied hit list than Italy, partially because of the territory's vulnerability to air attacks, and partially because of the rich resources that were being funneled into the Nazi war machine. All the Allies had to do was tell Hitler what he wanted to hear.

Documents were legitimized by a Nazi ... who hated Hitler

So, here's the elephant in the room: How on earth could this possibly have worked? According to Ben Macintyre's "Operation Mincemeat," the Allied intelligence agents may have had some help from the other side. Reports of the courier's untimely death, and the recovery of the documents he carried, found their way to a German intelligence agent named Lieutenant Colonel Alexis Baron von Roenne. Von Roenne was, at a glance, everything the Nazis could possibly want in an ally, and was appointed to his position by Hitler himself.

Von Roenne not only confirmed that the contents of the letter were legit and referenced an imminent attack at Sardinia, but he added that any mentions of an attack on Sicily were simply Allied attempts at misdirection. He relayed that the so-called Sicily hoax was code-named Brimstone, and wrote: "The circumstances of the discovery, together with the form and contents of the despatches, are absolutely convincing proof of the reliability of the letters."

But here's the thing: Von Roenne actually hated Hitler, the Nazi party, and everything that they stood for. Macintyre suspects that he knew the whole Sardinia thing was fake, and legitimized it as a way to sabotage the Nazis in a massive way. Von Roenne was also responsible for passing along false information fed to him regarding the D-Day invasion, and his end wasn't a happy one: He was executed as an anti-Nazi conspirator in October of 1944, hung from a meat hook and left to die.

The culmination in Operation Husky

As bizarre as it was, Operation Mincemeat was a resounding success. When the Allies did, in fact, attack Sicily on July 9/10, 1943, they found it vastly under-defended. According to the Imperial War Museums, it was that lack of defense that allowed for a blindingly fast take-over: Those troops that were stationed there had no idea that anything was coming their way, and 38 days later, Sicily was under complete Allied control.

It's impossible to stress just how important it was: Even before the German troops that were on Sicily retreated to the Italian mainland, Benito Mussolini and his government were overthrown and replaced with a new regime looking to make peace with the Allies. Securing Sicily meant having a stepping stone on the way to cutting a swath through Nazi-occupied Europe, and without a doubt, Operation Mincemeat helped make that happen.

It was only much later — when it became clear just how much of an impact the plan had — that Ewen Montagu was quoted as giving a less-than-kind but perhaps honest appraisal of the life of the man they'd turned into William Martin, saying (via the BBC), "The only worthwhile thing that he ever did, he did after his death."

The true story was forgotten for a long time

It's not a stretch to say that the outlandish plan involving a dead man and some fake documents had a huge impact on the outcome of the war, and just as shocking is the fact that it was nearly forgotten. Charles Cholmondeley stayed with MI5 until 1952, when he decided to go the route of marrying, moving to the countryside, and selling agricultural equipment. He died in 1982, and didn't even tell his wife what he'd done during the war.

Ben Macintyre's extensive research for "Operation Mincemeat" found that although Ewen Montagu had revealed the heart of the operation in his book "The Man Who Never Was," there was a lot that was left out, changed, or overlooked — including the identity of perhaps the most important man in the story: the corpse. Montagu died in 1985, and with his death it was believed that the identity of the man who had saved countless lives with his own ignominious end would remain a mystery.

It wasn't until 1998 that an amateur historian named Roger Morgan was sifting through pages and pages of documents, and found a single instance where military censors had missed redacting his name. It was only then that he was identified as Glyndwr Michael, and his name was finally completed on his gravestone, marking his final resting place in Huelva, Spain's Cementerio de la Soledad.