The Life And Career Of Mickey Rooney

He wasn't always known as Mickey Rooney. Born Joseph Yule Jr. in 1920, he headed to the stage and then the big screen — and by the time he was 6 years old, he had become so firmly associated with his first big character that he took that character's name in real life: Mickey McGuire.

Stardom can be touch-and-go after being so strongly associated with a single role, but after that show ended, it seemed like it was only going to be up, up, and away for Rooney's career. He made a name for himself playing Andy Hardy in the long-running film series, and he was an incredibly popular co-star for Judy Garland. For years, he was one of MGM's highest-grossing stars. It seemed he had it all.

But behind the scenes, Rooney lived a very different life than the sort of characters he became famous for playing. Never having known a life out of the spotlight, Rooney's off-screen struggles would only get worse as he aged out of the teen roles he played for a shocking amount of time. Confronted with shifting attitudes and the relentless march of time, Rooney's real-life story was the sort of roller coaster that only child stars can experience.

He was born... and headed to the theater

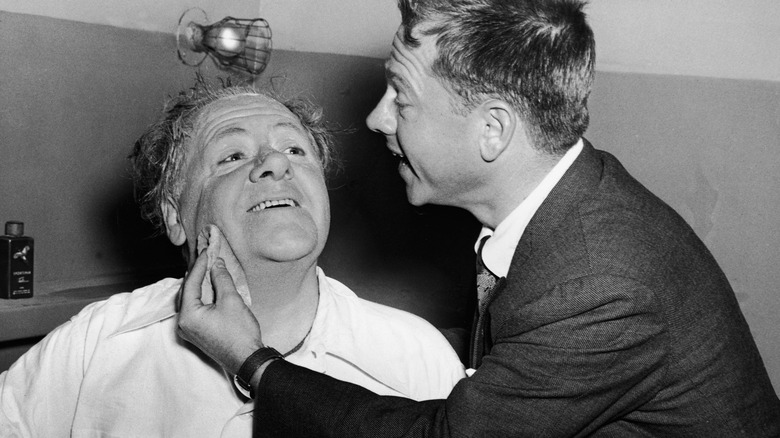

It's not unusual for children to follow in their parents' footsteps, and that's precisely what Mickey Rooney did. His father (left) was a comedian and his mother was a dancer in the same vaudeville troupe that both had joined under similar circumstances. While his father had emigrated from Scotland and his mother had been born in Arkansas, they both found their way to the stage after being orphaned incredibly young.

Rooney wrote in his memoir, "Life Is Too Short," that his parents were back on the road performing just weeks after he was born. And he went with them; he wrote that when he was born, the doctor had told him, "Okay, kid, you've been resting for nine months. Now get to work." (To say that he'd been resting is only part of the story, because his mother had been dancing all the way up to six weeks before she gave birth.)

Rooney recalled, "I spent a good deal of time backstage, sleeping in a tray in a baggage trunk and waking when the spotlights flashed around me. ... It's no wonder, then, that I've always enjoyed the lights of the theater, no wonder that even now, when I open a refrigerator door, I feel like performing."

He was onstage at 17 months old

While the term "child star" might bring to mind images of precocious little tots warming the hearts of miserly adults, Mickey Rooney's life as a child star started well before he was that old. According to his memoir, "Life Is Too Short," life as a performer started when he was barely able to walk.

Rooney was just 17 months old when he found himself toddling around the vaudeville stage, and he wrote that his very favorite spot was under the stage. It was there that he sat and watched the grown-ups, and crouched with his favorite toy: a mouth organ, tied around his neck. That's where he was when one of those adults caught him, telling him that if he was so interested in what was going on above, he could get out and perform. Shoved out onto the stage, he played his little instrument and promptly ran off, crying.

The audience loved him, and for the promise of an extra three dollars a week, his parents agreed that he would be on the stage. He was given a tiny tuxedo and paired with one of the other adults: "When I put on the tuxedo, I became a little adult," he wrote. "I started talking like an adult. Talk, talk, talk. ... This was a new game for me, the talk game. ... I was eighteen months old, and I was making my first professional appearance on the stage."

Ava Gardner became his first wife after he relentlessly pursued her

Mickey Rooney was already an established star by the time he met the actress who would become his first wife. He wrote in his memoir that he was on the set of "Babes on Broadway" when he met Ava Gardner: "I had known many beautiful women in my lifetime, but this little lady topped them all." When she turned down his offer to take her to dinner, he wrote that while he was shocked, he also didn't give up. He'd become bored of the adoration he got from most women, and asked her again, and again... and again, until she said yes.

After they started dating, he asked her daily to marry him, too. She finally agreed, but not everyone was sold on the idea. When they went to MGM head Louis B. Mayer, Rooney wrote that he was so angry "Ava was cringing in the corner. She'd never met Louis B. Mayer before this... she'd never seen me any better than this, standing my ground against the most powerful man in my world."

The wedding went ahead, but the marriage wasn't a happy one. In "Love Is Nothing," Gardner's biographer, Lee Server, recounted that it wasn't long before she grew sick of his gambling habits and having others in their circle telling her about the latest woman he was cheating on her with. Soon, she left.

He had a heartbreaking amount of tragedy in common with Judy Garland

Mickey Rooney charmed the nation in his Andy Hardy films, and he wasn't acting alone. Judy Garland was in several of them, too, and as recounted by the podcast You Must Remember This (via Slate), they had a lot in common. They had been working from their earliest days, were supporting their single mothers, and had complicated feelings about their absentee fathers.

Garland reportedly fell madly in love with Rooney, but even as she played his always-platonic friend onscreen, she stayed that way in real life, too... even as she watched him chase every other woman he saw. In the same year she starred in "The Wizard of Oz," they appeared in "Babes in Arms" together, and were sent off on a grueling PR tour that had them performing as many as 34 shows a week. As recounted by Jane Ellen Wayne in "The Golden Guys of MGM," it had a devastating effect on Garland. Already insecure and bullied by the studio for her appearance, she took Rooney's friend-zoning as proof there was something wrong with her.

At the same time Rooney got his draft notice for World War II, Garland was starting down the road of addiction to alcohol and pills. Rooney would later gain some valuable perspective, saying that he had bought into the Hollywood hype and chased the women who were renowned for their beauty... while overlooking Garland.

Louis B. Mayer was fanatical about Mickey Rooney's reputation

Louis B. Mayer was the famous — or infamous — studio head of MGM. It wasn't long after signing Mickey Rooney that it became clear the studio had struck gold, but Mayer saw a massive problem with everyone's favorite all-American teen. Even as the nation loved him for his portrayal of the innocent Andy Hardy, the media had a field day with his drinking, gambling, and tendency to have a different woman on his arm every time someone snapped a picture.

It was such a big deal that according to "The Golden Guys of MGM," Mayer had a sit-down with Rooney to tell him that he needed to be every bit as lovable as his onscreen perona — and Mayer took some extreme measures to make sure that happened. Rooney was assigned a PR guy named Les Peterson, whose only job was to make sure Rooney behaved.

Still, even after Peterson started working his magic, there was another problem: Rooney's father had come back into his life, and happened to be billing himself as "Mickey Rooney's Father" in his own live show in Los Angeles. That may have been acceptable... had it not been a burlesque show. After threats of lawsuits failed, Mayer ended up hiring Rooney's father at a $100-a-week salary. The job? Nothing — just stay out of trouble.

His WWII service wasn't without perks

Everything changed when World War II broke out, and that went for Mickey Rooney as well as the rest of the country. He was filming "National Velvet" at the time, and he wrote in his memoir, "Life Is Too Short," that even though Louis B. Mayer assured him that he had contributed to the war effort by appearing in a patriotic film, he wanted to do something more. After initially washing out and being refused because of his high blood pressure, he asked to be retested, was accepted, and in May of 1944, headed into the military.

He went from movie star to Army recruit in just three days, and it wasn't easy at first. Fights broke out between Rooney and guys who were convinced he was getting special treatment, and no one pulled any punches. But even though Rooney said he earned the respect of his fellow soldiers, those perks were definitely there. By the time he made it to the European front, he had spent a lot of time peeling potatoes. But he also wrote that instead of being in the line of fire, he was deployed as part of a unit tasked with entertaining the troops. Among their biggest worries were coming up with entertaining shows and moving their unit through dangerous territory. He also wrote about finding meaning in visiting wounded soldiers, and even running into one of them again years later in San Francisco.

His career floundered after the war

Mickey Rooney may have found some surprising purpose to his military career, but he struggled to find meaning post-war. It wasn't easy: In the years leading up to the war, his movies grossed somewhere in the neighborhood of $3 billion. And while he did eventually find his footing as an adult actor, it was a big adjustment.

The problem, observes Time, is that the war had changed not only the world's geopolitical landscape, but also the people who had survived to live in it. They didn't want to see the wide-eyed innocence that Rooney had become famous for depicting — that ship had sailed in favor of a grittier sort of feeling that innocence was gone. His career wasn't helped by the fact that he decided to jump ship from MGM, the company that had made him famous. When he tried to do it on his own, the only things he starred in were low-quality films that no one really wanted to see. Even his attempt at playing his signature character, Andy Hardy, as an adult was a flop, and he had no delusions about the work he was putting out. He would write of his 1950s and '60s-era films, "Most of them were crap."

Mickey Rooney was married eight times

The most famous of Mickey Rooney's eight wives was undoubtedly his first, Ava Gardner. His divorce from Gardner was followed by his 1944 marriage to Betty Jane Rase, and he would describe the marriage as a generally unhappy one, where they had nothing in common: "I gave her what she seemed to want, the old-fashioned, male chauvinist pig solution: I kept Betty Jane home, barefoot and pregnant, literally."

Their divorce was finalized in 1949, and six hours after the papers were in-hand, Rooney wed again. His marriage to Martha Vickers got just a few pages in his memoir, and shortly after they divorced he was married again. Rooney tied the knot with Elaine Mahnken in 1952; his gambling was the downfall there, as her ex-husband had been shot and killed over his own gambling debts. That marriage lasted six years, until he met and moved in with the woman who would become his fifth wife, Barbara Ann Thomason.

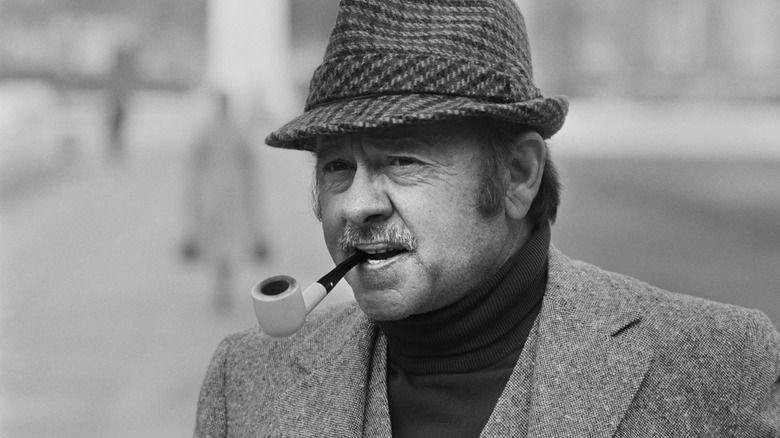

Of his sixth wife, Margie Lane, Rooney wrote in his memoir, "I was so drugged out then that I hardly remember her now. I'm told we were married one hundred days." Next was Carolyn Hockett (pictured), a customer relations rep Rooney met in Miami. Things ended in 1974, when she asked him to sign divorce papers. Finally, he married country singer Jan Chamberlin, and in his memoir he was quick to debunk the oft-repeated story that when they met, Chamberlin had been dating his son.

Wife number five was murdered by a jealous lover

In 2005, The Guardian sat down to talk to Mickey Rooney's son Michael, a successful choreographer. The interview didn't entirely go as planned. When the reporter apologized for not knowing which of Mickey's many wives was Michael's mother, Michael waved off the apology and explained, "What happened was — the story is kind of intense: My mother was murdered."

He went on to explain that what unfolded during the period his parents were getting divorced was a murder-suicide that involved a man his mother had been dating. Barbara Ann Thomason (pictured) had been killed at home, and he continued, "We [Michael and his siblings] were in the house when it happened. But I don't remember a thing. We were scurried out and told we were going to see the movie 'Mary Poppins.' It wasn't like, oh, your mother's dead upstairs."

The children were adopted by their grandparents, and Michael credited them with giving them a solid upbringing that had nothing to do with show business. Only a toddler when his mother died, Michael said that he didn't know the truth until about a decade later. He reflected, too, that his own normal upbringing was in a sharp contrast to his father's world: "Up until 10 years ago, show business was all he talked about. ... He always feels like there's a camera in front of him, or a spotlight, and he is number one."

He saw nothing wrong with his notorious Breakfast at Tiffany's role

By the time of Mickey Rooney's death in 2014, Paramount had officially denounced his "Breakfast at Tiffany's" role as being so toxic that it needed to be addressed in a documentary included with the film's rerelease. The Wall Street Journal went a step further and condemned the role as being the one that normalized the sort of racial stereotypes and film portrayals that minorities have been subjected to for years. And Rooney was largely unrepentant.

Deseret News spoke to him in 2008 after a California film series decided not to show "Breakfast at Tiffany's" because of his role, and his comments were less than apologetic. Claiming that it was just supposed to be funny, Rooney said, "Never in all the more than 40 years after we made it — not one complaint. Every place I've gone in the world people say, '...you were so funny.' Asians and Chinese come up to me and say, 'Mickey, you were out of this world.'"

Rooney addressed it in his memoir, "Life Is Too Short," although not in quite the way that might be expected. Rooney wrote that he was "downright ashamed" of the role, adding, "I was too cute as, get this, an eccentric Japanese fashion photographer living in a posh New York apartment."

His eighth wife and her son were accused of elder abuse

In 2011, Mickey Rooney testified at the request of the Senate Special Aging Committee, saying that he had been forced to turn over all control of his affairs to his eighth wife, Jan, and her son, Chris Aber. According to The Hollywood Reporter, she responded to accusations like this: "Mickey was a 90-year-old man who was in and out of it mentally and was easily influenced by other people."

THR uncovered a slew of abuse charges, along with witnesses who had come forward to claim that they had seen Jan hitting her husband. Along with that were accusations that Aber had been behind the theft of $8.5 million — an accusation that had ended with a $2.8 million settlement the year before Mickey's death. (As of 2015, Aber had yet to pay anything toward the settlement.)

Problems allegedly started in 1998, when Mickey was prescribed medications that Jan was in charge of administering. Even as Mickey kept working, witnesses testified that his pay — usually in cash — was handed directly to Aber. Mickey would allegedly be forced to read from written scripts and to live in a filthy home while his wife's family reaped the benefits of his decades of work, and the same year that he died, seven of his children filed papers with the court attempting to gain access to their father. Mickey passed away before things could be settled, and his final wife continued to claim his pension.

If you or someone you know is dealing with elder abuse, you can find resources and support at the National Adult Protective Services Association website.

Conflict and confusion ensued after his death

Mickey Rooney passed away in 2014 at the age of 93. According to his obituary, his death came after a long illness. The Hollywood Reporter claims things were far more complicated than mainstream news outlets let on. Rooney's eighth wife, Jan, and her son, Chris Aber (who also had acted as Rooney's manager) were almost immediately in court, fighting seven of his children for his estate. Although he left a will, it didn't really help clear things up to anyone's satisfaction.

According to The Guardian, the will cut everyone out of his estate except for one stepson, who stood to inherit all that Rooney had left: $18,000. Indignities followed: He lay in a morgue for weeks while the family fought, and when the funeral was finally held, it was a tiny affair with only one star in attendance. That was Mickey Rourke, who recalled, "It was a pathetic sight to see him in what looked like a ... $85 polyester gray suit, with his little hands folded, looking so tiny and all alone" (per The Hollywood Reporter).

It's perhaps appropriate, then, that The Guardian recalled this particular quote for his obit: "The American public is my family. I've had fun with them all my life."