Hedda Hopper: Old Hollywood's Most Notorious Gossip Columnist

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Hedda Hopper was the queen of Old Hollywood gossip. She wielded unparalleled influence over the film industry and even its biggest stars lived in fear of what she might write next. At the height of her power, she had millions of devoted fans all around the country. An article or radio broadcast from Hedda Hopper could blast an aspiring performer into superstardom, but she could also destroy careers – and frequently did. She was a zealous conservative and reserved her harshest criticism for anyone who disagreed with her.

Hopper's mass appeal coincided with broader changes in media during the Golden Age of Hollywood. As described in Jennifer Frost's "Hedda Hopper's Hollywood: Celebrity Gossip and American Conservatism" before the 1940s, the majority of published stories were news. Throughout the 1940s-60s, gossip about the personal lives of celebrities became the most popular stories in newspapers, on the radio, and on television. Hedda Hopper, who had been created by the studio system and yet viewed Hollywood as a den of vice, was uniquely poised to dominate this changing media landscape.

She was born a Quaker

While Hedda Hopper would go on to be known as an extremely powerful figure in Old Hollywood, she had humble beginnings. Born in 1885, she lived on a farm in rural Pennsylvania for the first years of her life. Her family were Quakers, and she was one of nine children.

When Hopper was three years old, her family sold the farm and moved to the city of Altoona, where her father became a butcher. Thinking of Hopper in her famously glamorous clothes and extravagant hats, it can be hard to imagine her working in a butcher shop, but after she left school in 8th grade, Hopper worked full-time in her father's store. While she was willing to work, Hopper always believed that she would be better suited to a different life, and she was willing to steal from her family to get it. When her father refused to pay her for working in his shop, considering it part of her responsibility to the family, Hopper took it upon herself to pilfer the money that she felt she deserved for her work. Secretly, she saved this money as a fund to begin her new life – one that she hoped would take her to the stage.

She changed her name so her husband could remember it

The name "Hedda Hopper" would become infamous in Hollywood, but she wasn't born with it. Originally, her name was Elda Furry. Like many women, Hopper changed her last name when she got married. Strangely, she changed her first name for her husband, too.

Hopper began her career as an actress in New York City, performing in musicals. She was reportedly not a particularly gifted singer or dancer, but Hopper's long legs landed her a job as a chorus girl. She fell in love with the show's star, DeWolf Hopper. As described in Hopper's 1952 book "From Under My Hat" her family was appalled by the relationship. He was older than her father, completely bald, and had unsettlingly blue skin because he gargled with silver nitrate, believing it had health benefits. Hopper, however, found him dazzling.

As described in Hopper's 1963 book "The Whole Truth and Nothing But" her new husband had four ex-wives, Ella, Ida, Edna, and Nella, and struggled to keep their names straight. To try to make things easier for him, the new Mrs. Hopper consulted a "numerologist" or believer in the mystical power of numbers, to select a new first name for her. They settled on Hedda. As bizarre as it might seem to turn to magic for a new name, it was not unusual for Hopper. She also pretended to have been born on a different date based on a numerologist's advice.

She wouldn't tolerate sexual harassment and her career suffered

There was a pervasive culture of sexual harassment in Old Hollywood. It was more or less expected that aspiring actresses would have to dodge the advances of men on set. If they wanted to get ahead, it was likely that they would have to cater to powerful male producers who assumed that they would be willing to go on dates and provide sexual favors to get a good role in a film. Hedda Hopper, however, had strong moral views about sex and wouldn't compromise them.

After years of working in theater, Hopper finally landed a role in a film: "The New York Idea." Her success made her husband extremely jealous, and ultimately led to their divorce. Hopper arrived in Hollywood alone with her son. She made some silent films, but eventually lost her MGM contract altogether and struggled to make a living that would support her and her child. This was very likely because she was unwilling to tolerate the sexual harassment and expectation of sexual quid pro quo for roles that were common in Hollywood.

Despite her profound distaste for sex outside of marriage, Hopper was desperate enough to consider working as the manager for an all-men escort service. Soon, however, she found a niche that would make her one of the most powerful people in Hollywood: writing a gossip column.

She was of the most feared people in Hollywood

In 1937, an MGM publicist suggested that Hedda Hopper might make a good columnist, even though she didn't have much experience writing. He had unwittingly set Hopper on a path that led to almost unprecedented power and influence in Hollywood. Although she held no official role in the film industry, Hopper became one of most feared people in Hollywood, and was proud of it. As quoted in the Saturday Evening Post, when she earned enough money to buy a mansion in Beverly Hills, she called it "the house that fear built."

The studios understood that Hopper's venomous column could be a weapon – one they could use. While damaging information about their stars getting out could jeopardize a film's success, the studios used the threat of a scandal to control the actors that worked for them. Morality clauses in the stars' contracts allowed the studios to unceremoniously fire them if they stepped out of line – and columnists like Hopper were always looking for the next shocking story about a star's transgressions.

Hopper didn't work for the studios, however, and she chose her own targets. She could be merciless. While positive reviews from her could make a young actor into a star, when an actor did something that she considered amoral, she wouldn't hesitate to obliterate them in the press, and delighted in destroying careers.

She was known for her hats

Hedda Hopper was famous for her unique fashion sense. Typically, Hopper wore suits in feminine pastels, but her trademark was a vast collection of extremely extravagant hats. In the documentary "Hedda Hopper: Hollywood's Gossip Queen" Hopper describes hats as her obsession.

Hopper's interest in clothes predated her fame, and the body type that made it difficult for her to get roles as a leading lady made her perfect for the world of fashion. Hedda Hopper was 5'7, which was considered tall for an actress. In her book "From Under My Hat" Hopper recounted taking off her heels and talking to the casting director in her torn stockings so that she wouldn't seem to tower over the leading man. When Hedda Hopper arrived in Hollywood, MGM's head of costuming, the famous Adrian Adolph Greenberg, was not put off by her height and thought she was the perfect model for costumes. Hopper always had an interest in clothing, even writing articles about fashion before finding her niche in gossip. While she would never be a particularly successful performer, her sense of style, and hats in particular, would become famous.

Hopper concealed Hollywood secrets

Hedda Hopper's columns could be malicious and personal, revealing the most intimate details of a star's private life to the public, but there were some lines that she did not cross, and those lines were mostly drawn by the studios. That didn't mean that she was entirely under the thumb of Hollywood producers, however. When she had a particularly damaging piece of gossip about a particularly profitable star, studio execs would have to negotiate with Hopper to keep it quiet. As noted by Hollywood expert Gavin Lambert (via Vanity Fair) they had to offer Hopper something she valued more than that particular scoop. Once, it was a small role in a film. Sometimes it was money. Often, it was an even more scandalous story about an actor the studio was willing to leave out to dry.

While Hopper's columns revealed shocking secrets about movie stars, they never went behind the scenes on how movies were actually made. In fact, Hopper intentionally kept the details of filmmaking from her fans. In an interview with Daily Beast, film critic Loreena Longworth explained that the studios preferred that audiences not know how the film industry worked, because they feared it would ruin the immersion. Everything from the business of how the studios financed their films to the fact that professional stuntmen stepped in for performers in dangerous scenes was considered off-limits for gossip columnists. Hopper might have had complex feelings about Hollywood, but she kept its secrets.

She had a famous feud

While some people believe that the MGM publicist who first recommended that Hedda Hopper become a gossip columnist did so purely to help out a former star, others believe it was an intentional attempt to undermine the power of Hollywood's reigning gossip queen: Louella Parsons. Whether or not it was part of the plan, Hedda Hopper certainly did challenge Parsons's hold on Hollywood. Today, Parsons is probably best remembered for her infamous feud with Hopper.

There is some debate over whether or not Parsons and Hopper really hated each other as much as it seemed. As described in "The First Lady of Hollywood: A Biography of Louella Parsons," some believed that the two were actively working against each other and hoping the other's career would fail, while others thought that the two were working together to make it seem like there was conflict and that the feud was entirely manufactured for headlines. The truth was likely somewhere in between. The two certainly resented each other's success but clearly benefited from the publicity of fighting with each other.

While her dislike of Parsons was real, it would not have been out of character for Hopper to manufacture a fight for attention. In fact, she was regularly fighting with all kinds of Hollywood personalities. In George Eels's "Hedda and Louella" one of her acquaintances is quoted as saying, "Hedda was shrewd in picking fights with people who were more important than she was. It increased her stature."

She was extremely conservative

While Hedda Hopper's critics often referred to her as a fascist, as noted in Jennifer Frost's "Hedda Hopper's Hollywood: Celebrity Gossip and American Conservatism," Hopper's views were more closely aligned with extremely far-right Libertarian politics. She was a believer in what she considered traditional values and used her power and influence over Hollywood to enforce her beliefs. Her most vicious attacks were reserved for those who she perceived as gay, foreign, Black, or politically left-leaning. Hopper was highly ambitious and above all was striving to expand her reach with fans around the country, but she also had a distinct moral agenda, one which she was highly adept at promoting to her followers.

Many of Hopper's colleagues, particularly Louella Parsons, were also conservative, but as described by film critic Loreena Longworth, Hopper was "committed to far-right politics with religious fervor." Hopper may have been a part of the entertainment industry, but she saw herself as a political activist and moral authority.

A lot of her stories were lies

Some of Hedda Hopper's gossip was true. She had tipsters all over Hollywood and, as noted in her autobiography, she would sometimes spy on celebrities herself for stories. She lived across the street from leading man Errol Flynn, who had a famously fraught love life, and after getting in loud arguments with his wife, would knock on her door to ask her not to publish anything she had overheard. Despite this, she often made up stories completely. When "Wuthering Heights" star Merle Oberon demanded to know why Hopper was targeting her, Hopper admitted that she had no real reason, saying that she was doing it for "sheer bitchery."

Famously, Hopper ran nonstop stories claiming that Joseph Cotten (a frequent collaborator of Orson Welles) was about to divorce his wife due to an affair with the young star Deanna Durbin, despite the fact that the two had never dated and Cotten had no intention of leaving his wife.. According to Cotten's autobiography, "Vanity Will Get You Somewhere" he responded by forcefully kicking the bottom of her seat at a political event they were both attending. Hollywood historian Laurie Jacobson states that Cotten sent Hopper "flying across the room," though Cotten himself said that he had only managed to "disturb the flower garden on top of one of the outrageous hats for which she was renowned."

She believed strongly in the Hollywood Blacklist

During the Red Scare, there was a moral panic that communist influences were infiltrating the film industry. The resulting witch hunt forced many industry professionals out of Hollywood. Hedda Hopper, who had always used her influence to harass stars who she felt were too left-leaning, approved of this censorship and did everything in her power to stoke the anti-communist fires already burning in Hollywood. She even communicated directly with infamous FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and attempted to get him to leak her confidential information that she could publish.

"Naming names" or outing others as communists was something that the government encouraged accused communists to do through a series of hearings by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) but it was something Hopper had already been doing for years. As described in "Hedda Hopper's Hollywood," she considered publicly accusing stars of being communist sympathizers not only a good way to rile up her audience but her civic duty. While HUAC and Hollywood executives alike generally considered former communists who gave up the names of their former friends to be absolved, Hopper was not so forgiving and would do her best to end the career of anyone who she viewed as ever having been too liberal, regardless of their current politics.

Hedda Hopper began the campaign against Citizen Kane

In 1941, it was widely believed that "Citizen Kane" would never be released. In satirizing the media mogul William Randolph Hearst, screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz and writer-director Orson Welles had made themselves many powerful enemies – including Hedda Hopper.

As described in David Nasaw's biography of Hearst, "The Chief" Welles arranged for Hopper to have a private screening of "Citizen Kane" before it was released. Although there were rumors that the film was based on Hearst, at that time, everyone involved with the film had denied it. When Hopper saw "Citizen Kane" she knew immediately that her staunch anti-communist ally Hearst was the target. Hopper told Welles directly that he would never get away with this, to which he replied, "Oh, yes I will."

Hopper got word to her sometimes rival and devout Hearst supporter Louella Parsons, and what followed was an aggressive campaign against "Citizen Kane" and its director. As described by The New Yorker, Hopper threatened to investigate and expose anyone involved with the film and even attempted to force anyone involved who wasn't an American citizen out of the country. The FBI itself came to consider "Citizen Kane" a communist attack on Hearst and American industry, driving Welles out of Hollywood and the United States altogether within the decade. "Citizen Kane" however would come to be known as the greatest movie ever made.

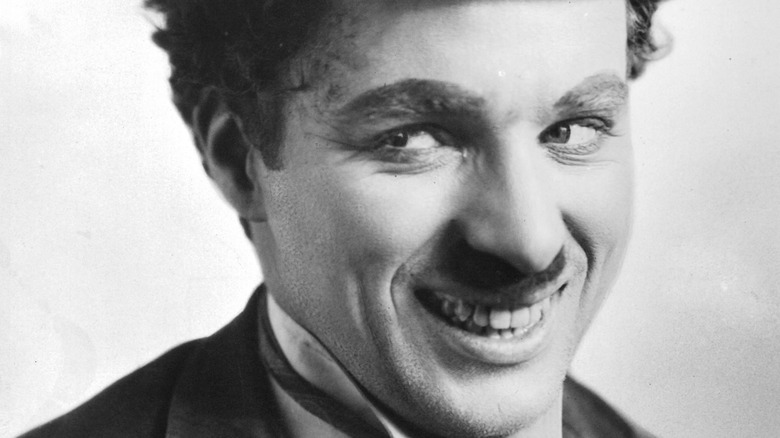

She forced Charlie Chaplin out of the country

Although he was twice her age, young actress Joan Barry had a brief, passionate relationship with revolutionary filmmaker and comedian Charlie Chaplin. The relationship is believed to have ended when Barry broke into his home brandishing a gun. Joan Barry wasn't willing to let the relationship go, so she turned to the most powerful woman in Hollywood: Hedda Hopper.

Barry claimed that Chaplin was the father of her child, something which a blood test would refute. For Hopper, however, the truth was irrelevant. She was famously opposed to promiscuity and wanted to make a public example of Chaplin, showing what would happen to people that she caught having extramarital affairs. Hopper wielded her influence against Chaplin, and he found himself at the center of a very public scandal and paternity trial, which he lost, causing him to pay child support to Barry.

The trial was over, but Hopper never gave up the crusade against Chaplin. As described by Jennifer Frost's 2007 article in the Australasian Journal of American Studies, Hopper stirred up her base and collaborated with Red Scare anticommunist forces, including J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI, to harass Chaplin. The furor she created directly led to Chaplin's U.S. visa being revoked while he was overseas promoting a film. Chaplin never returned to Hollywood.

Hedda Hopper targeted foreign and Black film stars

In addition to targeting anyone with even slightly liberal politics, Hedda Hopper saved her most vitriolic attacks for foreign and Black stars, and would often work to humiliate them publicly. She was particularly enraged if they attempted to date white American stars.

When Grace Kelly dated the famous Russian Italian designer Oleg Cassini, Hopper attacked them both, writing that Kelly would be better off with an American man. Hopper also disapproved of Elizabeth Taylor's relationship with British actor Michael Wilding, and as described in "Hedda and Louella" even had them both over to her home to try to persuade them not to marry. She tried desperately to convince Taylor that he was too old. When that didn't work, she attempted to spread rumors that he was secretly gay – a favorite tactic of Hopper's. As recounted in Donald Bogle's biography of Black film star Dorothy Dandridge, Hopper targeted Dandridge simply for dancing with a white man, an act that Hopper claimed would lead to "race riots."