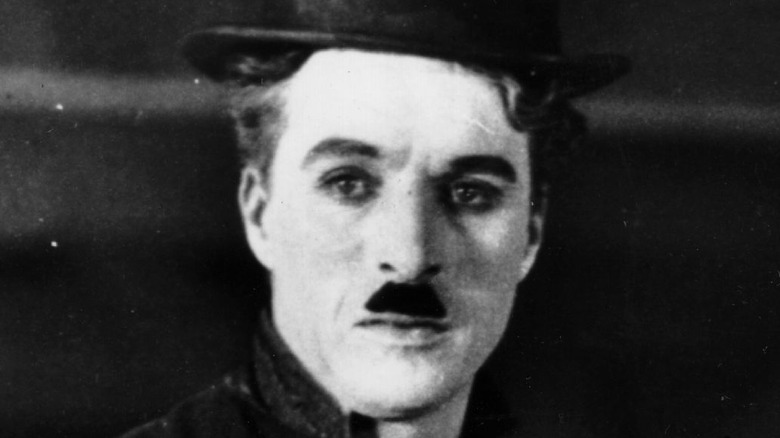

The Untold Truth Of Charlie Chaplin

Charlie Chaplin is one of the 20th century's most famous comedic icons. He was born in London in 1889 — near the end of the Victorian era.

Chaplin's parents separated when he was young, and his mother struggled to provide for her children. Chaplin spent much of his early life in and out of workhouses and on the streets. Things changed dramatically in 1915. According to History, that's when he signed a massive contract with Essanay, making a whopping $1,250 a week. Adjusted for inflation, that comes out to around $34,655 — and that was just the start. Another company raised that to $10,000 a week the following year — or about $257,660 in today's market.

It was only onward and upward from there, and along the way, Chaplin was also able to negotiate complete creative control over the films he released. The result is that what you see on the screen is exactly what he wanted audiences to see, and it led to him being lauded as one of cinema's greats.

His life wasn't without tragedy and controversy, though. Let's look at some of the lesser-known moments that shaped the life of one of the world's most famous comedic actors.

A caring foster mother taught him right from wrong

Charlie Chaplin was onstage at a young age. According to History, he was 5 years old when his mother, a music-hall artist, found herself unable to sing during a performance, so he was shoved into the spotlight to cover for her. But it wasn't all smooth sailing, and his early life was a series of struggles.

He didn't forget those who helped him the most, though, and according to a recently unearthed interview, that included the aunt of one Effie Wisdom. The Guardian reports that Wisdom was 92 when she gave her 1983 interview, which was only discovered by the British Film Institute about four decades later. In it, she recalled how her aunt had become something of a foster mother to the destitute Chaplin — and when he started going down the wrong path, she corrected him.

"He used to go up Lambeth Walk and pinch," Wisdom recalled. "He'd come home with four eggs one day in his pocket. He came home with a pair of boots one day he'd nicked." While he couldn't exactly return the eggs, Chaplin was made to return the boots amid reminders about where the life of a thief was bound to end up: intersecting with law enforcement.

Wisdom's aunt promised Chaplin's mother that she would care for Chaplin and his brother, and did. She fed and clothed them, and Chaplin never forgot it. Once he hit it big, Wisdom remembered: "He used to send my aunt so much money because she used to look after him."

His memories from the workhouse are heartbreaking

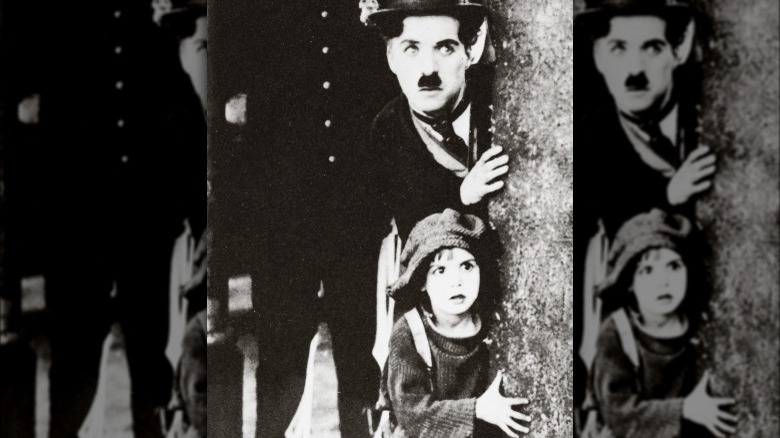

According to records kept by the city of London, Charlie Chaplin and his older brother, Sydney, first entered Newington Workhouse in 1896. By then, they were the sole responsibility of their mother, Hannah, a theater performer who was suffering from the loss of her voice and an inability to find work onstage. Chaplin wrote about their time in London's workhouses in his autobiography. It inspired the events of Chaplin's 1921 film "The Kid" (pictured above), but it's heartbreaking stuff.

Chaplin didn't really understand what was happening... until the family entered Lambeth Workhouse later, and authorities there separated him and his brother from their mother, as was the typical practice. After just a few weeks at Newington, the brothers — then 7 and 11 years old — were transferred to another facility, called Hanwell Residential School.

Chaplin wrote: "At Hanwell we were well looked after, [but] it was a forlorn existence. Sadness was in the air."

Chaplin recalled that one of the only times he saw Sydney during their time at the school was when the older boy brought him buttered rolls, smuggled out of the kitchen. Sydney was eventually transferred to a training ship designed to prepare navy recruits, while Chaplin stayed behind. The boys eventually returned to their mother.

Lambeth Workhouse was later the home of the Cinema Museum, and in 2017, The Guardian reported that Chaplin's family issued an open letter to the people of London, asking for their support in keeping the museum open.

Charlie Chaplin's first gig was clog dancing

Historian AJ Marriot is the author of "Chaplin — Stage by Stage," and during the course of extensive research for the book, he found that Chaplin's first big, paying gig was a surprising one: He was hired by the clog-dancing panto group the Eight Lancashire Lads (via the Lancashire Post).

Marriot wrote that Chaplin joined up with the troupe in Manchester, and by the time the traveling group made it back home, he was well established and made his Blackpool Pavilion debut in June of 1899. It would have been an exotic foray into show business, but historians over at Spitalfields Life suggest that it wasn't easy for the young Chaplin.

Chaplin later wrote: "After practicing for eight weeks, I was eligible to dance with the troupe. But now that I was past 8 years old, I had lost my assurance and confronting the audience for the first time gave me stage fright. I could hardly move my legs." Still, he now knew what he wanted to do. "I would like to have been a boy comedian," he later wrote, "but that would have required nerve, to stand on the stage alone."

Newspaper reviews from Chaplin's shows lauded the boys for their clog-dancing prowess and their singing skills, and it wasn't long before Chaplin moved on to other stage shows that included a run with a production of "Sherlock Holmes" (pictured).

His solo debut was a disaster

According to the Lancashire Post, biographer AJ Marriot says that Chaplin toured quite a bit with groups like Casey's Circus and in a series of traveling plays. It wasn't until 1907 that Chaplin took the stage by himself, going back to a long-standing dream of becoming a stand-up comedian. It didn't go well.

Spitalfields Life reports that his very first gig was in Whitechapel, at the Foresters' Music Hall. It was a trial run — he was booked for a week and agreed to perform without pay, but he left after the first night.

London, he later recalled, was enamored with Jewish comedians. Chaplin thought he'd hop on that bandwagon, don a beard, and perform some Jewish satire. He wrote: "Although I was innocent of it, my comedy was most anti-Semitic and my jokes were not only old ones but very poor."

Chaplin had only told a few jokes when the heckling started, and it wasn't long before the audience was throwing things at him. He continued on, not realizing what might be making the largely Jewish audience so angry, until it finally clicked. He walked off-stage, took off his makeup, left the theater, and never went back.

He would later write: "I did my best to erase the night's horror from my mind, but it left an indelible mark on my confidence. The ghastly experience taught me to see myself in a truer light."

He worked to lose his accent

It was silent film expert Kevin Brownlow who interviewed Effie Wisdom — one of Charlie Chaplin's childhood friends — as he was making a three-part documentary series in 1983. Her interview came too late to be included, but The Guardian reports that Brownlow recognized the importance of her memories of Chaplin.

In the interview, she talks about knowing Chaplin as a child, and says that at the time, he loved performing slapstick routines for the local kids. He had also been determined to do whatever it took to become rich and famous, and that included losing his cockney accent. When Wisdom met him post-fame, they talked about it: "I said to him, 'You're talking all posh. What made you?' He said, 'I had to, I went to elocution classes, they made me.'"

Interestingly, he didn't seem to like his voice all that much. In 2021, POV spoke with Peter Middleton and James Spinney, the directors of "The Real Charlie Chaplin." When they started research for their documentary with the goal of giving an inside look at who Chaplin really was, they found that very few recordings of his natural, unrehearsed speaking voice exist. That was in large part because Chaplin hated giving interviews and almost never allowed them to be recorded. There were some notable exceptions — like a 1966 interview with Life — but they're few and far between.

He buried his first million

According to PBS, extensive research has explored how growing up in poverty might impact people into adulthood, and it's undeniable that it does. Experts cite chronic issues such as continued worries about homelessness and going without, all the way to the development of health problems. Charlie Chaplin definitely grew up poor, and according to Jane Scovell, author of a biography about Chaplin's fourth wife called "Oona: Living in the Shadows," Chaplin's ongoing fear of poverty was what led him to take his first million dollars and bury it under a tree in their yard (via Ozy).

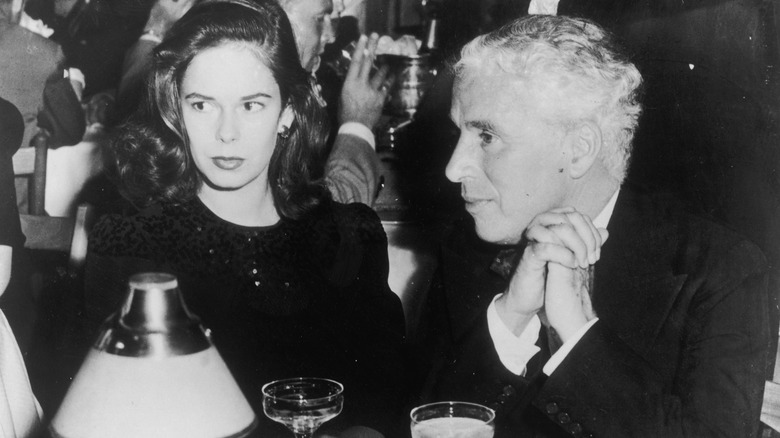

That was fine... for a while. In 1948 — five years after Chaplin married Oona O'Neill (pictured above, with Chaplin) — the actor was targeted in Senator Joseph McCarthy's Communist witch hunt. Chaplin was subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee, and he was so upset by the accusations that while he was on his way to visit England for the first time in a few decades, he decided he and Oona weren't going to live in the U.S. anymore.

But what about the money? Scovell says there's no way to tell if the story Chaplin's friends and family told was true. But according to their version of events, Chaplin sent his wife back to the U.S. with instructions to dig up the cash, sew the $1,000 bills into the lining of her mink coat, and wear it back to England.

Charlie Chaplin did a WWI fundraising film that was never finished

According to The History Press, historian and author Roger Foss says that by 1916, Britain's entertainment industry had set its sights on raising funds to support the country's war effort. Foss — who is the author of "Till the Boys Come Home: How British Theatre Fought the Great War" — says that fundraisers ranged from selling autographed postcards to staging special shows. In 1917, they included the efforts of Harry Lauder's Million Pound Fund for Maimed Men, Scottish Soldiers, and Sailors.

The idea was to get some seriously big names to stage performances and make films to help fund an assortment of welfare groups and war charities. One of the short films made for Lauder's project was done by Charlie Chaplin. (Lauder, it's worth mentioning, had a major stake in this: His son died on the front lines in 1916.)

Film historian Kevin Brownlow says that Chaplin and Lauder started on a film that featured the two men visiting Chaplin's movie studio (via Charlie Chaplin). Pieces of the film exist, but Brownlow says that it seems to be unfinished and was apparently never shown.

He's not sure why it remained uncompleted, but at the time, attitudes about Chaplin were split. Many believed his comedy was an important morale booster, but others thought he should be out there fighting instead of getting what was viewed as special treatment. There were even parody songs about his lack of service, but many believed Chaplin was more valuable doing what he was already doing.

He had a half brother who had to fight to be recognized

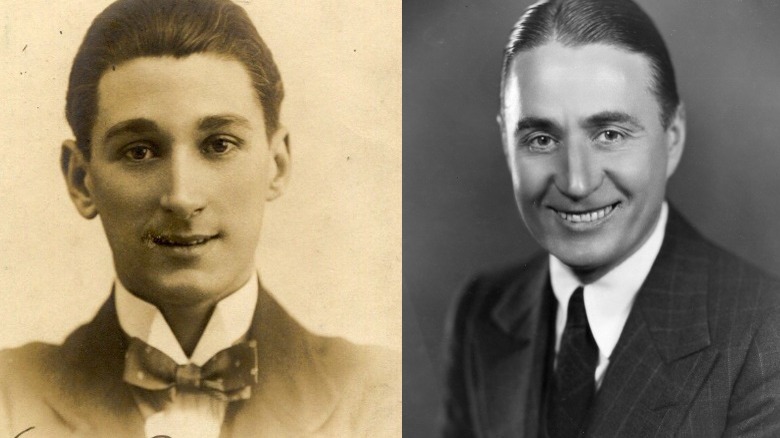

Charlie and Sydney Chaplin (right) spent their childhood in and out of workhouses, and while the brothers leaned on each other throughout those trying times, there was another half brother who was removed from their mother's custody by his father, a vaudeville comedian named Leo Dryden.

According to Charlie Chaplin, Wheeler Dryden (left) was just a baby when his father took him away from his mother. It wasn't until he was an adult that he found out Chaplin was his half-brother, and after repeatedly failing to get in touch with him, he wrote a 1917 letter to Chaplin's then-costar, Edna Purviance.

The letter has been preserved by the BFI, and in it, Dryden explained that his father didn't tell him about his relationship to Chaplin until 1915. Over the next two years, he said he had written multiple letters to Chaplin in an attempt to get in touch with his long-lost brother. "I don't want his money," he wrote to Purviance. "I only want his friendship and brotherly interest and encouragement. Surely I am not asking much?"

Wheeler Dryden traveled to the U.S. in 1920 and finally met his brothers.

His innate musical talent went unrecognized

According to American Songwriter, the first time Charlie Chaplin's voice was heard on-screen was in a gibberish song that his character, the Tramp, was forced to make up on the spot after losing the cuff of his sleeve — which had his lyrics written on them.

That's perhaps not entirely surprising, given Chaplin's background on the stages of London. But what is surprising is that, according to The Guardian, that was only one small part of Chaplin's musical skill.

It started when he was a teenager and taught himself how to play both the violin and the cello. Strangely, what he never learned was to read or write music, and when it came time for him to compose, he sang to an arranger who would then transcribe Chaplin's vision. He composed most of the music for his movies, writing in his autobiography that he had never been happy with composers who wanted to assign his movies happy, upbeat, comedic sounds: "I wanted the music to be a counterpoint of grave and charm, to express sentiment."

Chaplin often claimed that some of the songs came to him in dreams, and composers have recognized homages to greats such as Gershwin, Brahms, and Debussy in his work, lauding him for an innate skill that was often overlooked.

His perfectionism must have been unbearable

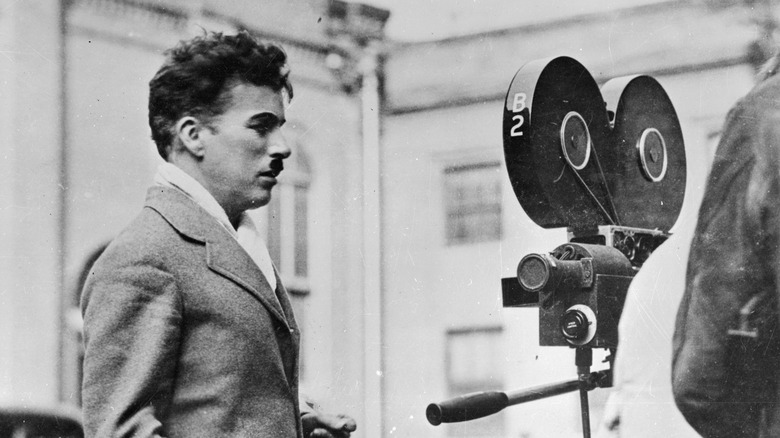

History reports that when Charlie Chaplin signed his 1917 deal with Mutual, he didn't just get a ton of money — he also negotiated absolute creative control.

He took that authority over his work very seriously, and there are a few examples that demonstrate just how much of a perfectionist he was. CNN recounts the story of his work with Virginia Cherrill in "City of Lights" (pictured). Cherrill plays a blind flower-seller who says the line, "Flower, sir?" to Chaplin's Tramp. Chaplin insisted on 342 takes of her delivery of the line before he felt it was right... for the silent film.

That wasn't an isolated incident. According to documentation from the Library of Congress, Chaplin tended to shoot a heck of a lot of footage. His 11th film for Mutual was "The Immigrant," and the final version was a two-reel movie contained on about 2,000 feet of film. While filming, though, he went through continuous attempts to make it perfect, and the result was a whopping 90,000 feet of film.

Part of his drive came from the fact that he was both directing and acting in the movie, so he would record his performance to review it, then go back to make adjustments. His perfectionism was so front-and-center, in fact, that at one point he attempted to make a film that involved literally only himself doing everything.

It's believed Charlie Chaplin knew a lot about what was going on in Nazi Germany

Charlie Chaplin's Tramp character and Adolf Hitler share some physical similarities, particularly in the moustache area. DW reports that Nazi propaganda was denouncing Chaplin as Jewish as far back as 1926. Even though he wasn't Jewish, he refused to go on record as publicly distancing himself from the Jewish faith.

And then came "The Great Dictator," and here's where things get weird. According to Vanity Fair, Chaplin started filming in September of 1939, and got some pushback. According to the BBC, Britain was fresh out of its "appeasement" position, and the U.S. hadn't entered the war yet. Making fun of Hitler in such a big way was still something that most countries were hesitant to do, but Chaplin had no such reservations.

He released the film in 1941 to outstanding success. But here's the thing: Amid the slapstick comedy is some serious stuff, including a depiction of Nazi concentration camps. That knowledge hadn't been made public yet, but according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Chaplin had some of the details right.

Chaplin claimed that he wouldn't have made the film if he had known what was going on in the camps, but that leads to another fact: Chaplin financed thousands of Jewish people fleeing from Nazi Germany, so much so that he was given the nickname "The 20th-Century Moses." How much did he really know? It's unclear.

Lita Grey's story was ignored for a long time

There's a lot of Charlie Chaplin's personal life that gets overlooked, and that includes the story of ex-wife Lita Grey. "The Real Charlie Chaplin" directors Peter Middleton and James Spinney found that, when the couple divorced, Grey was "vilified not only by the media, but by prominent intellectuals because of Chaplin's status as 'a genius'" (via POV).

Grey died in 1995, and her Los Angeles Times obituary reminded everyone that not only had Grey met Chaplin when she was 12, but that she was pregnant at 15 and married to him at 16. She reportedly said that he had long promised to marry her if she happened to get pregnant, but that when it happened, he tried to convince her to have an abortion.

When they divorced in 1927, it was a nine-month-long process, and she was granted a settlement for $825,000. (Adjusted for inflation, that's about $13.4 million in today's money.) It was thought to be the largest ever granted at the time, but the media still insisted on taking his side of the story, which involved lies and money. She, on the other hand, came forward with a slew of what The Guardian called "proto-Me Too accusations." While the courts ruled in her favor, the court of popular opinion did not, leading her to make the observation: "Awe is a kind of fear."