Hawaii's Red Hill Water Contamination Fiasco Explained

For 75 years, an underground military fuel storage facility in Hawaii was leaking. Sometimes the leaks were just a few gallons, and other times they amounted to tens of thousands of gallons. And with the island's aquifer nearby, it was only a matter of time before the leaking jet fuel contaminated the water supply. Even when the nearby drinking water was confirmed to be contaminated, the Navy refused to admit there was a problem. It took numerous leaks and countless protests by organizations like Kaʻohewai and Oahu Water Protectors for the Navy to finally agree to shut down the fuel storage facility.

But even this is turning out to be an arduous battle. And the longer it takes to defuel Red Hill, the longer people will be exposed to contamination. Every time one leak is plugged up, another one pops up in its stead. But this militarized exploitation is nothing new to the people of Hawaii. After the United States occupied Hawaii in the late 19th century, the island and its people were used in service of military aspirations. This continues to this day, as Indigenous Hawaiians watch the military contaminate the water and deny any responsibility.

As of June 2023, Red Hill has yet to be defueled. But the Navy maintains that defueling will begin by October 2023. Until then, the residents of Hawaii must hold their breath and hope there aren't any further contaminations. This is Hawaii's Red Hill water contamination fiasco explained.

What is Red Hill?

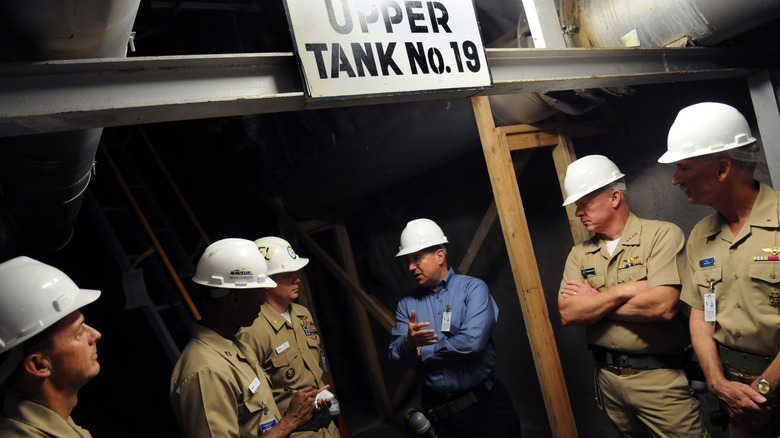

The Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility, also known as Kapūkakī, is a fuel storage facility in Honolulu, Hawaii, that is owned and operated by the U.S. military. Construction began in December 1940 (one year before the attack on Pearl Harbor) and was completed within three years. Nearly 4,000 workers were brought in from across the United States, laboring for hours in caves with temperatures of up to 120 degrees Fahrenheit. Civil Engineering writes that many workers described it to be like working in hell. But despite the vast number of workers that it took to construct Red Hill, only four Navy members work to keep it operational.

Built underground in a volcanic rock formation, a total of 20 fuel tanks make up the largest underground military fuel storage facility in the United States, with a capacity that exceeds 250 million gallons. The fuel tanks are connected to Pearl Harbor through three pipelines that run several miles through the island of Oahu. And roughly 100 feet below the fuel tanks is Oahu's fresh water aquifer, which provides water to almost 25% of the people on Oahu.

Although Red Hill was only used briefly in the second half of World War II, it remained operational as a fuel storage and transfer point and was considered to be instrumental in military campaigns like the Gulf War.

Leaking 27,000 gallons

In January 2014, the U.S. Navy confirmed that there was a leak at Red Hill, but it maintained that the leaking jet fuel didn't contaminate the drinking water. It wouldn't be until a few weeks later that the Navy would confirm that roughly 27,000 gallons of jet fuel had leaked and contaminated the groundwater. By June, the Navy was still finding tiny holes that were causing jet fuel to leak out.

Honolulu Civil Beat reports that although the Navy tried to blame the 2014 leak on contractor errors, in fact the Navy knew about the leak and was deliberately ignoring it and its potential to contaminate the island's drinking water well before the leak was publicized by the media. In response to the leak, the Navy agreed to an Administrative Order on Consent with the EPA, the Hawaii Department of Health, and the Defense Logistics Agency, according to The Georgetown Environmental Law Review, which involved upgrading the tanks in accordance with health and environmental safety measures. But there continued to be leaks, which the Navy suppressed information about in order to protect its image.

After samples revealed contamination in the groundwater, drinking water was also tested, but was reported to be within federal and state limits.

A long history of leaks

In May 2014, four months after Red Hill leaked 27,000 gallons of jet fuel, an article in Civil Engineering described Red Hill design as "so sound that few major alterations have been necessary." But in fact, the leak in 2014 wasn't Red Hill's first leak, so the designs clearly weren't as sound as people thought. And the leaks may have started as soon as five years after the storage facility was completed.

There is a lot of conflicting information as to how many leaks and spills Red Hill has experienced. And part of the uncertainty is due to the Navy's own poor record-keeping. According to Hawaii Business Magazine, up to six of the tanks showed no records whatsoever over the course of almost 50 years. Meanwhile, the Navy claimed after the 2014 leak that it started keeping adequate records as soon as the EPA started requiring more oversight of underground fuel storage facilities. (It's worth noting that underground fuel storage units also played a role in the Camp Lejeune water contamination fiasco.)

In total, it's believed that Red Hill has leaked at least 200,000 gallons of fuel over the course of 76 spills since it was constructed. But even this estimate might be conservative, with the Navy itself estimating that the number might be as high as 1.2 million gallons of fuel.

Oil in the harbor

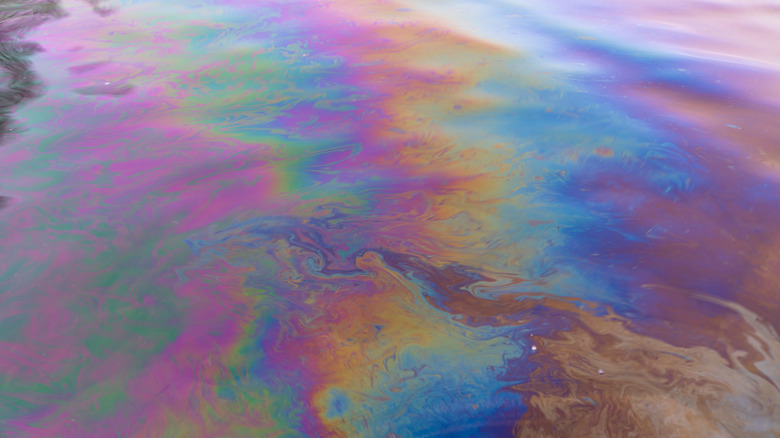

In March 2020, oil was noticed in the water of Pearl Harbor outside of the Hotel Pier. The same month, Honolulu Star Advertiser reported that the tank at Red Hill that had previously leaked 27,000 gallons of jet fuel was being brought back into commission after extensive repairs.

But clearly it wasn't just one tank that was the problem. One year later, during a clean-up of a smaller spill of around 100 gallons, the Navy revealed to Hawaii Public Radio that by March 2020, 7,700 gallons of fuel had leaked from Red Hill into the soil and water, and stated that the leak wasn't completely addressed until February 2021.

According to Honolulu Civil Beat, although Navy spokeswoman Lydia Robertson claimed that the oil outside the Hotel Pier wasn't directly connected to Red Hill, the Department of Health directly attributed the oil to Red Hill during its assessment. But the Navy tried to diminish the impact and severity of the leaks because at the time it was trying to get a permit to operate underground fuel storage facilities – a permit that was being contested by the Honolulu Board of Water Supply and the Sierra Club of Hawaii.

Leaking thousands more gallons

In May 2021, the Navy reported that over 1,500 gallons of jet fuel had leaked from Red Hill, but an investigation revealed that there had actually been a leak of over 19,000 gallons. The fuel went into the fuel suppression system and sat there for months, even causing the pipes to bend from the weight, reports CNN. A few months later in November, the pipes burst open, spilling fuel everywhere. But the Navy insisted that the liquid was diluted jet fuel and that it couldn't get out of the concrete tunnel and cause contamination.

But by the end of November, people who lived in military housing started complaining that their water smelled like jet fuel. At the same time, the Navy was insisting that the fuel didn't make it into the wells or the drinking waters. But as more and more people started experiencing nausea, vomiting, and skin-related issues, it became clear that some contamination had occurred.

One of the many lawsuits filed against the United States for negligence alleges that this leak in May is what "triggered a catastrophic spill that injected jet fuel into the Red Hill well, the drinking water source for the plaintiffs," per Feindt v. United States.

Contaminating the water supply

Despite the fact that the Navy constantly maintained that the drinking water supply wasn't contaminated by the repeated leaks at Red Hill, even the Hawaii Department of Health released an advisory by the end of November 2021 telling people to not drink or use the water. The Department of Health later reported that the water contained gasoline and diesel hydrocarbons up to 350 times higher than the standard acceptable levels. In March 2023, it was also revealed that the November 2021 contamination may have also included an anti-icing additive like antifreeze.

Affected areas included Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Aliamanu Military Reservation, and various military housing areas. Up to 4,000 families who lived in the affected housing were given temporary accommodations in hotels. But the military base isn't the only facility on the island that uses that water. In addition to affecting civilian areas, there were legitimate concerns about the aquifers being contaminated and affecting the water of up to 500,000 people on Oahu.

But despite shutting down the Red Hill well and the Aiea-Halawa well, the latter of which supplies water to 20% of urban Honolulu, the Navy continued to deny that the Aiea-Halawa well was contaminated. And according to The Guardian, some people, like Army Major Amanda Feindt, chose not to go against the U.S. Navy and continued to use the water until the Navy announced that it planned to stop using the storage tank facility.

Water contamination in civilian housing

While the Navy continued to deny that the Red Hill jet fuel leak had contaminated the water, the contamination continued to seep through the island, affecting civilian residences as well. According to Hawaii News Now, Kapilina Beach Homes in Ewa Beach, once a military housing area, remained connected to the Navy's water system without residents' knowledge, despite now being civilian housing. In addition, up to seven public elementary schools are connected to the Navy's waterline. Up to 93,000 people living on or near the military base were affected by the contaminated water, including Indigenous Hawaiians as well as settlers.

And while the Navy acknowledged that the water shouldn't be drunk, it continued to maintain that it wasn't responsible for contaminating the water supply. And while those who fell sick from the water on the military base were able to access military medical facilities, civilians living in Hawaii were denied the same resources. It would take until March 2022 for the Hawaii Department of Health to state that the drinking water affected by the Navy's jet fuel contamination was safe for consumption.

Sick from contaminated water

It didn't take long for the people who interacted with the contaminated water to report a variety of symptoms and illnesses. In a survey of 14% of the households affected by the contamination, 87% of people said that they had a symptom associated with the contamination. The most common symptoms included nausea, headaches, and skin rashes. Some of the children who were exposed to the contaminated water also experienced seizures and ended up in the emergency room.

Some people experienced severe swelling after using the shower. Jayden Bonilla, who was 17 at the time, told Hawaii News Now that, "My eyes were like puffed out. They tried to look at the back of my throat and they couldn't see anything because it was so swollen on the inside." Dr. Wendy Heiger-Bernays has also noted to Task and Purpose that toxic exposures of this kind can lead to a wide variety of illnesses, including effects "on the gastrointestinal, the digestive system, blood-forming cells, the neurological system, and certainly irritations with the skin."

It's estimated that at least 2,000 people fell ill because of the contaminated water, but the number is likely much higher considering how Red Hill has been leaking for almost 75 years. And when the Navy finally acknowledged that the water was contaminated, CBS reports that officials claimed to have initially misread the tests.

Finally agreeing to defuel

In December 2021, the Hawaii Department of Health ordered the Navy to shut down and defuel all of the storage tanks at Red Hill. But despite all the evidence that the jet fuel was contaminating the water and the pressure from activist organizations like Kaʻohewai and Oahu Water Protectors, the Navy dug its heels in and filed an appeal to continue operating Red Hill.

Although the Navy had claimed that it would address the leaking jet fuel, it resisted the order to close Red Hill because it claimed there were no immediate threats to people. Even though thousands of people had already sought treatment from injuries they sustained by using the contaminated water. And despite repeatedly claiming that there were plans to defuel, the Department of Defense continued to stall at giving a specific plan for defuelment.

In May 2022, the state of Hawaii was forced to issue another emergency order for Red Hill to defuel and shut down. And this time, the Navy was ordered to provide a specific plan for defueling and closing the storage facility within the year. The state rejected the Navy's initial plan on the grounds that it overlooked key details. In a revised plan submitted in September, the Navy announced its intentions to remove 104 million gallons of jet fuel at Red Hill by July 2024.

Leaking fire-suppression foam

Despite the plan to shut down Red Hill, the storage facility continued to be operational as the Navy dragged its feet. And in November 2022, there was another spill. This time, over 1,000 gallons of fire-suppression foam known as AFFF concentrate leaked into the nearby soil and underground facility.

Although it was stated that the drinking water wasn't compromised in any way, a worrying aspect of the leak was the fact that the Navy didn't know exactly how the leak happened. According to Honolulu Civil Beat, Navy Admiral John Wade simply claimed that, "Whatever happened, it is stopped." This also wasn't the first time that fire suppression foam leaked at Red Hill. In September 2020, roughly 5,000 gallons of AFFF concentrate leaked, but when confronted, the Navy lied to the Hawaii Department of Health about it, Honolulu Civil Beat reports. The EPA also reportedly didn't even know about the spill until 2022.

In December 2022, the Hawaii Department of Health maintained that there was no evidence of AFFF concentrate in the water. However, it stated that it will continue to "hold the Navy and Department of Defense accountable to provide more information on the spill."

Class action

In January 2022, a class-action lawsuit was filed against the Navy by civilians whose water was contaminated by the jet fuel leak. Another class action was filed in April 2022, which claimed that "after the spill, the Navy's modest efforts at remediation and 'assistance' have only compounded Plaintiffs' injuries and frustration. Their lives may never be the same," per Honolulu Civil Beat.

In August 2022, it was estimated by Navy spokeswoman Lydia Robertson that there were at least 186 claims under the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA), but this number continues to grow. And as more and more information that the Navy tried to suppress continues to come out, like the fact that the drinking water may have been contaminated with antifreeze as well as jet fuel, the lawsuits continue to be revised and updated. According to Stars and Stripes, some of the lawsuits also allege medical gaslighting by the Navy, claiming that its repeated denial of contamination was an active denial of the health issues that people were facing.

And it's not just civilians who are trying to hold the Navy accountable. In March 2023, three service members filed claims related to the contamination. Although a legal precedent known as the Feres doctrine typically prevents service members who are injured while on duty from suing the government under the FTCA, the plaintiffs maintain that the doctrine "cannot be used against off-duty service members that showered in and drank water poisoned by the Navy in their own homes," per CBS News.