Here's What Happens To Your Blood When You Die

In the hours and days following our deaths, the body breaks down and goes through many phases, changing color several times to produce a gruesome rainbow, and eventually rotting away to a pile of bones. The position and consistency of our blood also change quite a bit during this process, and the different stages can help morticians work out when you might have died.

Unless some whip-smart murderer has hidden your body far from view, or you've died in some remote location far from civilization, chances are this process will also be artificially interrupted by some arm of the funeral service. If your corpse will be viewed, your body will be tidied up, and the blood removed to make your grim carcass more palatable to your grieving loved ones.

The process of breakdown begins pretty much immediately when our hearts stop beating. On average, adults have at least six quarts of blood in their bodies and the flow of that life force throughout our body keeps our organs working. Of course, in death, the regular circulation of blood to our extremities and organs grinds to a halt and the temperature of your now useless meat suit will begin to cool rapidly.

The first phase of decomposition is known as pallor mortis and it will turn a corpse that deathly pale shade we find so chilling, in just 15 to 20 minutes. Algor mortis, the cooling-off process that accompanies it, will also make the body's normally balmy blood stone cold. The body cools down at a rate of about 1.5 degrees centigrade per hour, under normal conditions (per Florida State University).

Livor Mortis and the morgue

As the blood in your body begins to settle, gravity causes it to pool in certain areas, resulting in a blotchy discoloration of the skin (via Florida State University). This process is called Livor Mortis and it takes about two to four hours to occur. Investigators doing autopsies will often use the lividity of a corpse to work out the time of death by pressing on the surface of the skin to check if it leaves a white mark. This so-called blanching will cease to happen eventually when the blood has completely settled and become "fixed" at the surface, which only takes about six hours or so. After that, natural biological changes conspire to hold the blood where it pooled and settled even if the body's position changes. That part of the process is called fixation of lividity.

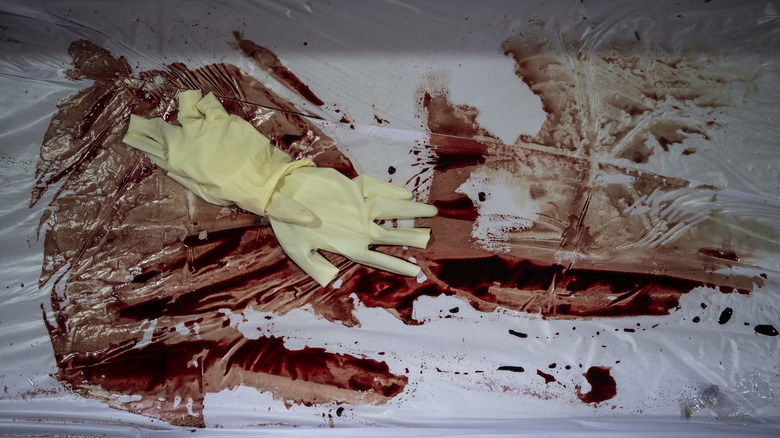

In the morgue, if you are not being cremated, morticians bring this unsightly process to a halt by removing the blood during the embalming procedure, thus ensuring that you do not turn into a pile of goo before the funeral. They do this by draining your body and replacing your blood with a formaldehyde solution. This remarkable fluid will freeze time and halt the process of rot, at least for a little while, keeping you looking fresh for the funeral or wake. During the procedure, the jugular vein is held open with forceps, and the blood is siphoned away.

Food for worms

Once so precious, the now useless leftover blood can present something of a problem for mortuaries, which are typically left with a gallon or two of the stuff after draining a corpse. The blood is unceremoniously washed down the drain, like other waste materials, and it can even clog up wastewater treatment plants if they aren't suitably alerted to the incoming torrent.

Assuming there is no human interference, though, after the first 48 hours, the body enters the late phases of decomposition. A corpse will eventually turn a frightening shade of zombie-like blackish green as the hemoglobin in the blood combines with gases and turns into sulfhaemoglobin — which is a "green pigment" created during that chemical reaction and is "found in putrefied organs and cadavers," according to the Merriam-Webster definition. The veins that once constantly ferried blood around the living body in particular will also begin to turn black, creating a marble-like appearance as the body falls apart.

How quickly the green tint occurs is dependent on temperature — in more temperate climates it takes just two to three days (via the National Library of Medicine). From here, the body begins to rot and microorganisms and insects will start to break the body down.

The process of decomposition is normally pretty uniform but there are some exceptional circumstances that can change how the blood appears as the body decays. For example, if the body has suffered massive blood loss the corpse will be uncharacteristically pale. On the other hand, nitrate poisoning can make a body turn brown during livor mortis, and carbon monoxide poisoning will make it appear bright red.