Religions You May Not Have Heard Of

Religion is a tricky thing. On the one hand, it helps people get through the train wreck that is everyday life, but on the other hand, it's been one of the most divisive factors in human history. People do amazing things in the name of their religion, and that goes both ways: amazing-incredible and amazing-terrible. When it comes to what religions, that's actually pretty well-established: It's estimated that about 85% of the world's population belongs to a religion, and of those people, the overwhelming majority — around 95% — belong to one of the three Abrahamic religions (Christianity, Islam, and Judaism), one of the main Indian religions (including Hinduism and Buddhism), or one of the major East Asian religions (which include Taoism and Shinto).

But these wildly popular religions aren't the only options out there, and less than 1% of the world's population subscribes to a faith that's a little more obscure — and it's been that way throughout history.

Some of those smaller religions are pretty familiar. While most people have heard of Wicca or Zoroastrianism, for example, there are tons of faiths that are less well-known. Religion — defined as a well-defined belief system in a higher power, recognized and honored with worship and adherence to a code of conduct — comes in many, many forms.

Coconut Religion

The Coconut Religion was established in Vietnam in the 1960s, and although it was also known by the seemingly harmless name of the Religion of Congeniality, the area's government deemed it highly suspicious and persecuted followers with a vengeance. At the head of the religion was the so-called Coconut Monk: Nguyen Thanh Nam was the son of a wealthy family who found his beliefs living in the shadow of the Seven Mountains.

He quickly became known for his religious practices: He survived solely on coconuts, encouraged others to perform acts of kindness, and meditated beneath imagery from other religions, including Christianity and Buddhism. Of the highest importance were ideas of peace — and at a time when tensions between North and South Vietnam were at their highest, it's easy to see how few in power would want to hear what he had to say.

Among those who studied with the Coconut Monk was John Steinbeck IV, who followed in the footsteps of his more famous father when he wrote about his experiences there. He wrote (via Tricycle), "[The Coconut Monk] was the true embodiment of the classic 'Don't Worry — Be Happy' posture that is eternally endearing and mystifying in a world gone mad." The monk's attempts at reaching out to authorities — including the government of Saigon — to encourage peace ended in 1990. He was killed in a fight between his followers and law enforcement, and afterward, those followers found themselves in court. Exactly what happened to them is shrouded in mystery.

[Image by Cserbell via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

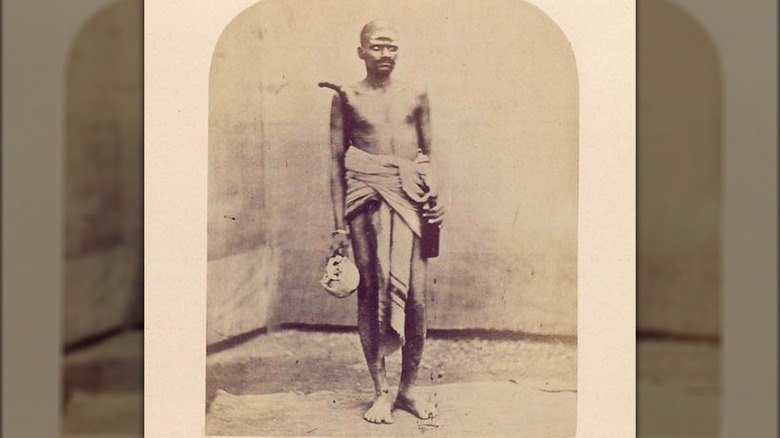

Aghori

When religious rites get into the sort of territory that mainstream society deems taboo, it's easy for things to devolve into little more than rumors and fear-mongering. That's what's happened to the Aghori of India — they've been around since some time in the 5th century BC, and anyone who has heard of them may have heard of rumors of a religion obsessed with eating the dead... with a little bit of necrophilia thrown in for good measure. How much of that is the truth?

Photographer Tamara Merino wanted to find out, so she headed to northern India to live alongside them for a month. First, the basics: Aghor is sort of adjacent to Hinduism in that they believe in and worship Shiva, the god of destruction. She explained to Refinery 29: "This is why they immerse themselves in environments where death surrounds them as a part of their daily routine. They eat human flesh for specific rituals and use human skulls and bones for ceremonies and jewelry."

But Merino also said that she learned there was more to their practices than a quick glance revealed. Not only were the rituals she witnessed deeply respectful, but they were rooted in the idea that life is sacred and that everyone is equal. Their connection with death, in fact, is credited with also giving them the power to heal and conduct exorcisms. "I was struck by how very human it all was," she observed. "They are a people full of endless love and respect."

John Ballou Newbrough's Faithists

John Ballou Newbrough may have continued being content as a dentist had he not found himself visited by an angel who dictated an entirely new version of the Bible to him. He published his Oahspe bible in 1882, and essentially, it taught that every prophet that had come before had preached the same universal truths. Once those words were passed on to man, they became corrupted... which, honestly, it's easy to see how that would happen.

Newbrough attracted a small group of followers, who headed into the remoteness of the American southwest to establish a commune where believers lived off the land and adopted orphans. Not a bad deal, right? Unfortunately, a series of misfortunes that included massive crop failures, disease outbreaks, and disagreements over doctrines meant that things never really took off. The Universal Faithists of Kosmon are still around, though, with a few hundred members and a temple in Brooklyn: They were profiled in The New York Times in 2018.

The Oahspe text (which isn't taken literally) is notable for having one of the first descriptions of an extraterrestrial spacecraft within its pages, and it also has some fascinating interpretations of other ideas. God, the Faithists believe, is an elected position temporarily given to a highly ascended soul — and any soul has a chance of getting to God-like heights if life is lived according to testaments that include abstaining from meat and being a generally good and thoughtful person.

Atenism

The Pharaoh Akhenaten was the father of the more famous King Tutankhamun, which is slightly ironic. Akhenaten took massive strides to make his mark on Egypt, but a lot of what he did was undone after his death — including overhauling the pantheon of familiar Egyptian gods and elevating a single figure, Aten, to the head of his new religion, Atenism. He was so intent on erasing worship of the other gods that during his 17-year rule, names and images of the pantheon were chipped and scratched off countless monuments. However, his would-be new Egyptian religion is shrouded in mystery today: Many of the writings and monuments he made and built were similarly destroyed.

According to the experts over at the American Research Center in Egypt, Aten was a figure that wasn't precisely representative of the sun but of the life-giving light that came from the sun. (His own name, changed from Amenhotep IV, meant "Effective for Aten.") One probable reason for the overhaul suggests that claiming he was the prophet of the nation's only god would — in theory — give him a massive power boost that set himself and his family up as direct conduits to this newly-elevated deity.

Interestingly, Akhenaten's new religion was clearly depicted in his generation's art: Images of the pharaoh and his wife, Nefertiti, have a distinctive appearance. They're elongated and otherworldly, which is thought to be a conscious decision to reflect a touch of the divine. Things reverted to the norm after his death.

Thelema

Aleister Crowley is perhaps most famously associated with the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, but he left the order in 1900. Four years later, he was honeymooning in Cairo when he sat down and, in just a few days, wrote "The Book of Law" and outlined the principles and beliefs that would become his religion, Thelema.

Crowley claimed that the book wasn't his, precisely, but instead that an otherworldly entity named Aiwass had dictated it to him. From the book, Crowley plucked three verses that were going to form the backbone of his religion: chiefly, "Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law." In other words, Crowley preached that it was up to each individual person to set and then follow their own ethical and moral guidelines. Dangerous? Tempting? Absolutely!

Crowley and his adherents practiced his religion at a communal home in Sicily before being kicked out by Benito Mussolini — and like many things, it sounded better in theory than it was in practice. Betty May's autobiography recounted seeing cats killed in ceremonies that included drinking their blood, while surrounded by murals that would make the illustrators of the "Kama Sutra" blush. Things really went sideways when one of their own died a bit mysteriously. The cause of his death is alternately given as complications from drinking cat's blood or a nasty case of typhoid from drinking from the abbey's polluted water source, but either way, it spelled the end of Crowley's Sicilian religious nightmare.

Raelism

In 2018, The Irish Times interviewed Moya Henderson, who had grown disillusioned with the Catholic faith she had been born and raised in; since becoming Raelian, she's risen to the head of the Irish movement. She summed up the religion as teaching that humankind's ancient ancestors were extraterrestrial and that those extraterrestrials would return once humans got organized enough to build an embassy and open Earth's door.

It was created by a French racecar driver named Claude Vorilhon, and Henderson explained that he'd based it on the Bible: "He talked of how the Bible was written in old Hebrew and then translated into Greek, Latin, and other languages, but that the word 'God' was mistranslated. The word in the original Bible was 'Elohim,' [and] the Elohim means 'those who came from the sky' and it was they who made us and the world as we know it."

Believers are expected to live a lifestyle designed to bring them closer to their alien ancestors, and it includes things like going vegetarian, skipping caffeine, undergoing a baptism, and practicing things like meditation and tithing to the church in order to fund the aforementioned embassy. Key are free attitudes toward sex, which include bans on homophobia and discrimination based on sex and gender. It seems pretty harmless, but it hasn't been without controversy: Supposedly in line with their promotion of world peace, their original symbol was a combination of a swastika and a Star of David. It didn't go over well.

[Image by Kmarinas86 via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Tengrism

Tengrism is difficult to describe, as it's meant many things to many different people. As it's explained by the Central Asian Bureau for Analytical Reporting, it's the religion of the nomadic people who have lived in the Asian steppe for centuries, and it's changed a lot over the years — particularly with the influence of Islamic missionaries.

Different groups believed different things, and because of the changes in theology, it's difficult to tell exactly what ancient nomadic beliefs looked like. It's generally thought that Tengrism is rooted in the idea that everyone and everything coexisted — as opposed to having humans on Earth and a deity up in heaven — and the spirits of ancient ancestors remained with their descendants. That made it accessible to everyone, instead of restricting the divine to priests. It also meant that everyone was responsible for living in a way that was respectful to the natural world and other life around them: Anyone who violated that wasn't condemned to hell, but would instead condemn their bloodline to a cursed existence.

Tengrism features a pantheon of spirits and demigods, and in charge of it all is Tengri, the sky. He's not only all-knowing, he's extremely tolerant, too: Tengrism could comfortably coexist alongside other religions, and not be bothered by sharing the room, as it were. Modern-day Tengrism is just as complicated, and while many Western people may not have heard of it, they have heard of one of the religion's most famous practitioners: Genghis Khan.

Summum

The tiny religion of Summum made national news way back in the ye olde times of 2008, when they went to court over the right to erect a monument that included their version of the Ten Commandments, called the Seven Aphorisms. The issue, reported by The New York Times, is that there was already a monument sporting the Ten Commandments in a public space, and representatives of Summum stated they wanted the same right. The case went to the Supreme Court, which sided with the city.

Reports at the time were mostly concerned with issues of freedom of speech and didn't really get into just what Summum was — which is a shame. The second of the Seven Aphorisms is perhaps the most interesting — "As above, so below; as below, so above" — particularly considering they observe the age-old practice of mummification — with a bit of an update.

As in traditional mummification, organs are removed and treated separately but are ultimately replaced. The entire body is treated in what's described as "a baptismal font filled with a special preservation solution made up of certain liquids, some of which are chemicals used in genetic engineering." Remains are wrapped and covered with layers of cotton, polyurethane, fiberglass, and resin, placed in a bronze or steel sarcophagus, and then filled with resin. Summum philosophy perhaps unsurprisingly deals with the cycle of the souls through life, death, and advancement of knowledge, teaching that personal experience is the only true way to acquire knowledge.

[Image by Summum via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.5]

I AM Activity

In 1930 — so the story goes — Guy Ballard (pictured, with wife Edna) was hiking on California's Mount Shasta when he was approached by a man who claimed to be the divine Saint Germain. He explained that he was an ascended Master of the I AM, and so, the I Am Activity was born, outlined in the pages of a text called "Unveiled Mysteries." In it, Ballard preached that wealth and energy went hand-in-hand, claiming that adherents would learn how to harness the divine energy that flowed through the universe, channeling that into personal gain and, ultimately, spiritual ascension.

Ballard — who claimed to be George Washington, reincarnated — headed the movement that asked followers to make the church their beneficiaries in all sorts of financial matters, which ended about as expected. After Ballard died nine years after his mountainside vision, his inner circle was accused of fraud. In the midst of claiming that they actually had done things that had averted national tragedy, Ballard's widow and I AM co-founder Edna didn't do herself any favors. According to the Los Angeles Times, she responded directly to an elderly woman who wanted her jewelry back: "If she'd brought as much love and blessing into the world as I have, she wouldn't be in this fix."

The movement took a bit of a less high-profile role as that all went down, but it's still around. By the 2000s, the I AM movement had morphed into a handful of different societies and had several hundred sanctuaries worldwide.

[Image by Vaivasvata via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Mithraism

The mystery religions of ancient Greece and Rome are fascinating examples of how people can keep a secret after all... unfortunately for anyone who wants to know what they were actually about. Characterized by rites and rituals that individuals had to be initiated into, the secrecy surrounding them has left modern historians to try to piece together exactly what they believed. It's not always easy, even for religions — like Mithraism — where some things have been unearthed.

No actual texts from anyone who was initiated into the Mithraic religion exist, so that's left a lot up in the air. It's even debated about whether or not Mithraism was an instance of Roman people adopting an Iranian god, which, if we all can't agree on that, what can we agree on? Not much, aside from the fact that Mithraism petered out as Christianity took over, generally swept under the rug and stamped out of existence with other cults and religions.

What we do have is imagery, and it's weirdly specific. Mithras is depicted as killing a bull by stabbing it in the shoulder and letting it bleed out, the blood running out to be consumed by a dog and a snake. Oh, and as if that's not a bad enough day for the bull, he's also got a scorpion poised to sting his very personal, delicate bits. Why? Who knows! There are plenty of theories about fertility and the cycle of life, but at the end of the day, no one's really sure.

Prince Philip Movement

It's the sort of thing that pops up on a meme on Facebook, seems unlikely, gets all kinds of snarky comments, then gets scrolled past — but it's absolutely true: There is a religion where, in a remote corner of the world, Britain's Prince Philip was worshiped as a god. When Philip died in 2021, the BBC profiled the members of two villages on the island of Tanna, who had revered him as what anthropologist Kirk Huffman once explained as a "recycled descendant of a very powerful spirit or god that lives on one of their mountains."

It's also worth noting that not everyone believed, and at the time of his death, his worshipers had dwindled to just a few hundred people. The idea was that Philip's marriage to Elizabeth II was the fulfillment of a prophecy that said one of their own was going to head out overseas, marry into power, and work to bring world peace. How did Philip get assigned the starring role in this powerful narrative? No one actually knows, but it is known that it was already a thing when he first visited the islands in the 1970s.

When his son, the then-Prince Charles, visited in 2018 after an elaborate mourning period, the rumor was that they were going to replace Philip with Charles. During Charles' coronation, villagers hosted the Acting British High Commissioner Mike Watters during a day of ceremonial drinking, dancing, and celebration.