12 Of The Worst Generals Of The American Civil War

It's hard to imagine, but it's only been just over 160 years since the American Civil War commenced in 1861. In the end, the war caused the deaths of more than 600,000 individuals and left an indelible mark on our country that can never and will never be erased. While much attention has been given to some of the top generals of the Civil War, like Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, and Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson, there were also some less-than-adequate performers, whose military ineptitude resulted in huge losses of life, among other things.

Looking back, even though the Union won the war, they were saddled with their fair share of poor generals like Benjamin "Beast" Butler and James Ledlie. Then again, the Confederates weren't all world-beaters, as the troops of Braxton Bragg and Gideon Pillow would have surely attested to. The Civil War was hell, and poor generalship only makes it worse.

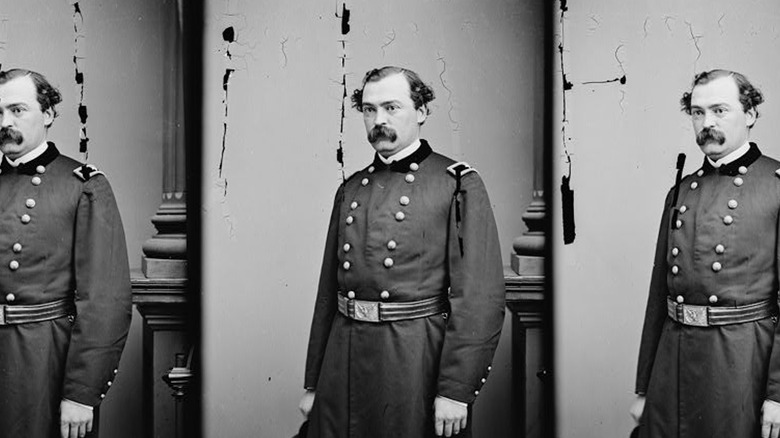

Union Maj. Gen. George McClellan

Among Civil War historians, Union Maj. Gen. George McClellan has a very controversial reputation. He became the commanding general of the Union Army in late 1861, but his tenure was rife with problems. While McClellan certainly gets credit for some early victories and for deftly organizing the Army of the Potomac, his actual command on the battlefield left a lot to be desired.

One of his most infamous blunders was early in the war, when he had the Confederates outnumbered by 75,000 men, yet he still refused to attack. McClellan overestimated the enemy's strength by 105,000 and was fooled by fallen tree trunks painted as guns — later sarcastically called "Quaker Guns" by his detractors. McClellan was often too timid to actually push his troops into battle, infinitely preparing his army for an attack he would refuse to order.

At one point, he was even given a captured copy of Gen. Robert E. Lee's battle plans, but his failure to send in his troops quickly allowed Lee to save his army from complete destruction at Antietam. President Abraham Lincoln took McClellan out of command for good after that. Though considered a victory, Antietam resulted in massive casualties, with McClellan failing to press the Confederates for more gains. McClellan would later run against Lincoln in the 1864 election, but he lost that, too.

Union Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler

To his detractors, he was known as "Beast Butler" of New Orleans, but to everyone else he was simply the ineffective Union Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler. Unfortunately for the Union, his nickname was less related to his battlefield prowess than it was to his contemptible policies during his time as military governor. Prior to the Civil War, Butler had served in both houses of the Massachusetts State Legislature and was also a longtime member of the state militia, too.

A born politician, Butler was better at negotiating in the halls of Congress than he was commanding troops on the battlefield. Things got off to a bad start for him at Big Bethel, where he and his troops were soundly defeated by the Confederates in one of the first battles of the war. His main claim to fame was taking over as the military governor of New Orleans following its successful capture by famed Adm. David G. Farragut. Yet, this is where he earned his nickname after instituting a law that practically legalized the abuse of Southern women by Union troops.

His remaining action as commander included failures during the Bermuda Hundred campaign and at Fort Fisher. During the Bermuda campaign, Butler didn't maximize on the potential advantage of a practically undefended Petersburg and instead led a series of uncoordinated attacks that lost the city. He was all but relieved from duty after a failed naval bombardment on Fisher in 1864. Unsurprisingly, Butler reentered politics following the war's end, later serving as both the governor of Massachusetts and in the U.S House of Representatives.

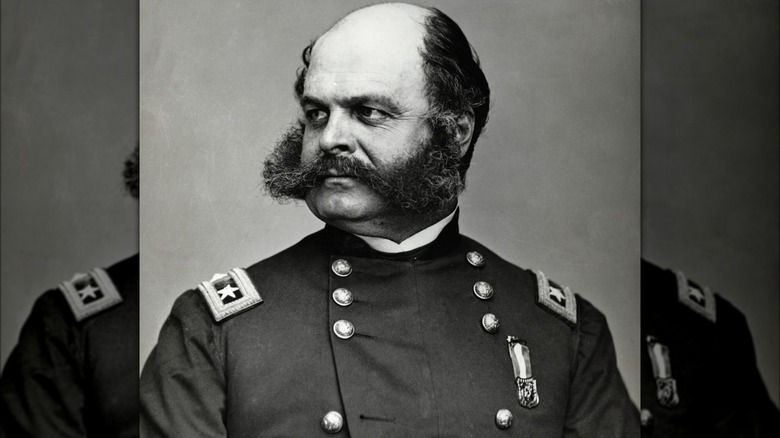

Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside

If awards were given for the best possible facial hair in the Civil War, Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside would have surely been a top contender. Sadly, his ability to style his sideburns was much greater than his skill in commanding soldiers during battle. When the Civil War broke out, Burnside — a West Point graduate — quickly rose to become a colonel, yet he refused command of the Army of the Potomac two times, acknowledging his own lack of experience, before finally accepting in late 1862.

Maybe his superiors should have listened to Burnside before promoting him. He delayed attacking Confederate forces during the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, before leading his troops into suicide at the Battle of Fredericksburg a few months later. Fredericksburg led to nearly 13,000 Union casualties, many of them due to reckless and futile frontal assaults on Burnside's orders.

His later conduct during the Vallandigham Affair was also controversial after he ordered the arrest and suspension of habeas corpus against Ohio antiwar Democrat Clement L. Vallandigham. While Burnside successfully liberated East Tennessee, his epic failure during the Battle of the Crater that left his soldiers to essentially become sitting ducks led to his final departure from the army. Burnside's reputation has been somewhat rehabilitated over the years as history has looked upon him more kindly, and postwar he served in both the U.S. Senate and as governor of Rhode Island.

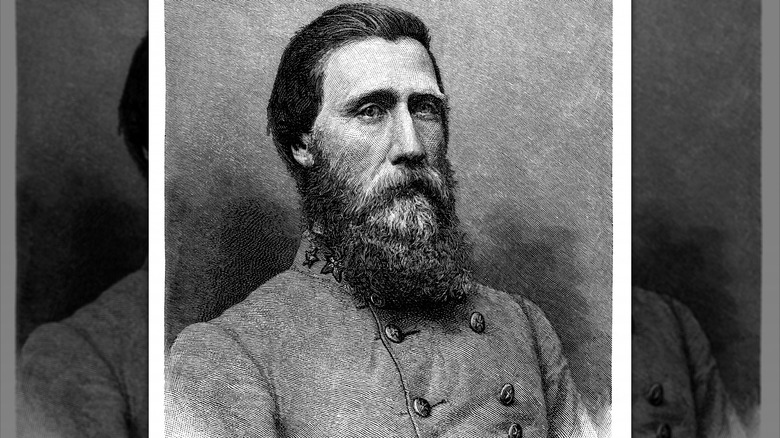

Confederate Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood

A commissioned officer of the Union Army, Confederate Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood resigned when the war began. He preferred to join the Confederacy, even though he was from Kentucky — a state that was split but remained officially loyal to the Union.

Hood performed exceptionally well during the early part of the war, particularly in Virginia and Maryland. He showed impeccable courage leading his troops and had success leading flanking maneuvers and assaults. However, he later lost the use of his arm and had his leg amputated following Gettysburg and Chickamauga, and the remainder of his career was marked by ineptitude and failure.

After pressuring Confederate officials, he was given command of the Army of Tennessee, but he promptly destroyed it in Atlanta and Nashville. In Atlanta, he lost more than 30,000 men after four separate assaults on Union Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman's troops were all repulsed in brutal fashion. Then, in Tennessee, he led "Pickett's Charge of the West" in 1864, during which he foolishly tried to have his troops overrun a strong Union position in Franklin, leading to incredible loss of Confederate life.

His army disintegrated after the Battle of Nashville, when he oversaw another 6,000 casualties after failing to repel another Union assault. He was then relieved of duty and transferred to Mississippi to report on military affairs. Upon arriving there and after realizing the cause was truly lost, he surrendered himself to federal officials in May 1865 and was immediately paroled.

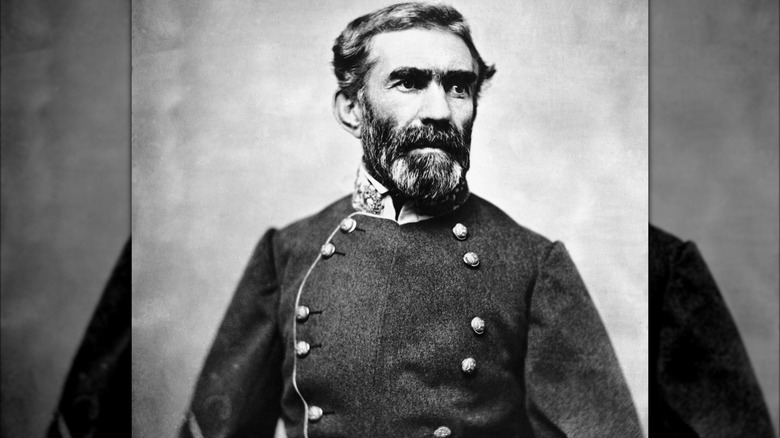

Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg

If you were to take a poll of the least-liked Confederate generals among the men in the Civil War, there's a pretty good chance that Gen. Braxton Bragg would have won first prize every time. A native of North Carolina, graduate of West Point, and a slave owner, Bragg fit right in as major general in the Confederate Army. He performed well at the Battle of Shiloh, showing grit and tenacity in spite of defeat, and he was also exceptional at organizing and drilling his men into fighting form.

However, Bragg's men detested and loathed his rancorous style of leadership, and at one point they even tried to assassinate him with an explosive. He was known for being salty and arrogant, and he controversially ordered the execution of a teenage soldier, ignoring appeals from the Confederate governor.

The biggest negative marks on Bragg's record come from his inability to follow up on his victories. During the Battle of Chickamauga in 1863, Bragg let a Confederate victory go to waste when he decided to retreat instead of pursuing the fleeing Union soldiers. This led to his subordinates petitioning the Confederate president for Bragg's removal, but he stayed in command.

He had done a similar move earlier in 1862 at the Battle of Perryville, when instead of following up on the Confederate gains he backtracked to safety. Both of these failures let Union armies escape, allowing them to eventually regroup and defeat the Confederates.

Confederate Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow

Many Civil War historians consider Confederate Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow to be one of the worst leaders in the entire war on either side. From Tennessee, Pillow was both a lawyer and a veteran before the Civil War broke out, and he stayed loyal to his native state and the Confederacy. Like other leaders, he initially performed well early in the war at the Battle of Belmont against Ulysses S. Grant, which led to his promotion. However, the wheels fell off almost as quickly as they were put on.

Pillow's commands at Fort Donelson and during the Battle of Stones River (Murfreesboro) were historically inept. At Donelson, Pillow's inexplicable decision to retreat following a hard-fought victory against Union troops under Grant completely undid all of the Confederate gains. Not only that, but when the defenses of the fort collapsed, Pillow decided to abandon most of the men and flee rather than stand with them and be taken prisoner, displaying exceptionally poor leadership.

Yet, all of that still pales in comparison to his alleged cowardice during Stones River. Pillow allegedly took cover behind a tree during the fighting, once again essentially abandoning the men under his command, which left them and troops under Maj. Gen. John C. Breckenridge to get eaten alive by Union guns. A stunning display of pusillanimity for a general, this was predictably the last time Pillow was given command of a Confederate field unit.

Union Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel

Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel was perhaps the most unique general on either side of the American Civil War. A native of the Grand Duchy of Baden in what is now Germany, Sigel received his education at a German military academy, graduating as a teenager. He came to the United States following the 1848 revolutions, setting up a school and joining the New York Militia.

Soon after the war broke out, he became a brigadier general in the Union Army after showing bravery at the Battle of Wilson's Creek in the summer of 1861, though some of his fellow officers disputed his actions and considered him incompetent. Sigel continued to have a decent, if unspectacular, career, that is, until the Battle of New Market in 1864. At New Market, Sigel faced troops under Confederate Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge, which included around 250 green, teenage military cadets from the Virginia Military Institute (VMI).

Even though he had more men and they were more experienced, Sigel lost to Breckinridge and the VMI cadets, suffering over 800 casualties. The tide of the battle only turned once the cadets entered the fray, and Sigel was never able to escape the humiliation of losing to a smaller army supplemented with teenagers. He was removed from command for almost the entire last year of the war, and he resigned his commission just as the fighting was ending.

Union Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks

In the Civil War, there were two kinds of generals: military generals and political generals. Political generals earned their commissions due to their political stature and reputation and were often less than ideal at actually commanding troops on the battlefield. One of the most obvious examples of political generals in the Union Army was the former governor of Massachusetts, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks.

After gaining his commission, Banks immediately ran into trouble against Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson during the Shenandoah Valley campaign. During the campaign, he earned ridicule with the nicknames of "Old Jack's Commissary General" and "Commissary Banks," because the Confederates were able to steal massive amounts of his troops' supplies from the field. At the Battle of Cedar Mountain, Jackson once again defeated Banks through superior generalship, with Banks sustaining far more casualties after refusing to retreat against a force three times his size. Shortly after, Banks was relieved from command and sent to do recruiting.

His final command was during the Red River Campaign, which was a complete failure. His plans for the campaign were overly complex and relied on almost perfect timing, and he completely underestimated his Confederate foes. Incredibly, Banks actually brought along political backers of his so they could attempt to procure cotton, making some believe he was turning a military operation into a personal escapade. The campaign failed after Banks' late arrival at Alexandria and his repeated retreats, leaving Louisiana in Confederate hands for the remainder of the war.

Confederate Maj. Gen. George Pickett

Unfortunately for Confederate Maj. Gen. George Pickett, he is probably most well known for the disastrous "Pickett's Charge" during the famous Battle of Gettysburg. It resulted in thousands of Confederate casualties in just a few hours and was one of the Confederacy's lowest points of the Civil War. Pickett himself does not deserve most of the blame, which lies with his superiors, but it is he who has always been synonymous with the failure.

In the antebellum years, Pickett was educated at West Point, though he performed the worst in his class. He fought well early in the war but was also known for leaving his troops to spend time with the woman who would later become his wife. Following Gettysburg, he once again failed at the second Battle of New Bern, when his forces were unable to overcome a powerful Union line and he ordered a retreat.

Later, Pickett was responsible for the execution of over 20 Confederate-turned-Union soldiers who were prisoners of war, a clear and obvious war crime, though he escaped punishment. Later, during the Battle of Five Forks, Pickett abandoned his troops to eat lunch and possibly drink whiskey, leaving them out of position and unable to receive his instructions. That partly led to the final destruction of the Confederate Army, hastening the end of the war. It was his widow who later rehabilitated his image, erroneously painting him as a hero and making him a symbol of the "Lost Cause of the South" myth.

Union Maj. Gen. John Pope

While Union Maj. Gen. John Pope may have had some early successes in the war, his tenure later became so disastrous that he was removed from fighting against the Confederates entirely. Prior to the war, Pope was another West Point graduate and Mexican-American War veteran, and an early general in the Union. He showed aggressiveness in operations in Mississippi, capturing thousands of prisoners, which led to his command of the Army of Virginia in 1862.

Yet, Pope was always squabbling with his fellow commanders, and he was considered arrogant by his soldiers and officers over his boasts and condescending attitude. Before the Second Battle of Bull Run, Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson's troops managed to get behind Pope's troops and capture the Union supply depot, taking away precious supplies before destroying it. Later in the battle, Pope ordered multiple doomed assaults against the Confederate troops, all of which were repulsed, and he eventually had to retreat. At Bull Run, Pope lost nearly double the amount of troops as the Confederates did, and his failure to contain Robert E. Lee led to the Confederate invasion of Maryland at Antietam a few weeks later. This would be Pope's last Civil War command.

In September 1862, barely a year after gaining his commission and less than three months after getting control of the Army of Virginia, Pope was removed to fight Native Americans in Minnesota. He never fought another battle against the Confederates.

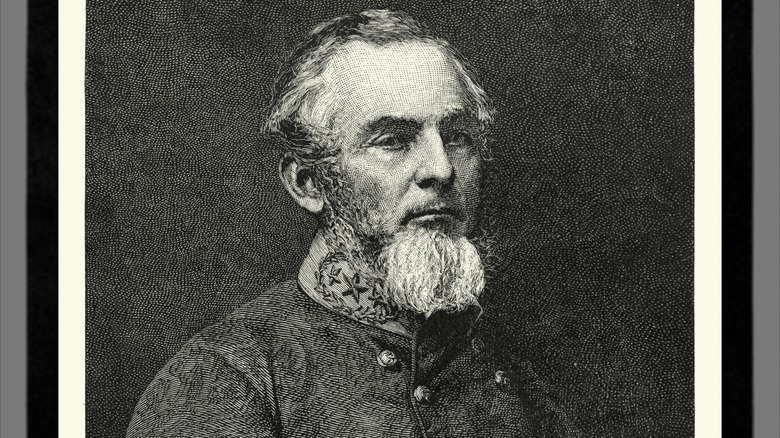

Confederate Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd

Even before the Civil War broke out, eventual Confederate Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd already had a tumultuous career and reputation. A former governor of Virginia and slave owner, Floyd became the secretary of war for the United States during the administration of James Buchanan. However, it was during his tenure as secretary that Floyd became a widely controversial figure. Accused by his critics as corrupt and nepotistic from the beginning, Floyd resigned in 1860 under a cloud of suspicion for potentially giving the Confederacy mounds of Union guns and matériel.

He soon joined the Confederate Army as a political general, and after being sent west his first command was at Fort Donelson, but he performed about as poorly as one could possibly imagine. Outmanned and outgunned by Union troops under Ulysses S. Grant, Floyd made the cowardly and spineless decision to abandon the majority of troops under his command and escape out the back door, leaving Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow to take the fall. It's hard to imagine a move more unbecoming of a general.

This would prove to be the breaking point for Floyd as a commander. Confederate President Jefferson Davis removed him from command over his fecklessness in Donelson, and he died just a few months later.

Union Brig. Gen. James H. Ledlie

Out of all the Union generals who served during the Civil War, there's a pretty good case to be made that Brig. Gen. James H. Ledlie was the worst of them all. More of a political general than a military general, Ledlie's tenure was disastrous pretty much from the beginning.

At first, Congress refused to even confirm his initial promotion to brigadier general, which could have been related to allegations that he had accidentally fired upon his own troops during the Battle of White Hall. His middling leadership continued through the Battle of North Anna, where he may have been drunk, but his ultimate failure was at the Battle of the Crater in 1864. While his troops trudged to their deaths, Ledlie's cowardice got the best of him, and he ended up abandoning his troops to (again) get drunk in a bunker.

After the Crater debacle, his superiors had enough of him. Put on sick leave for several months, Ledlie resigned before ever being given another command.