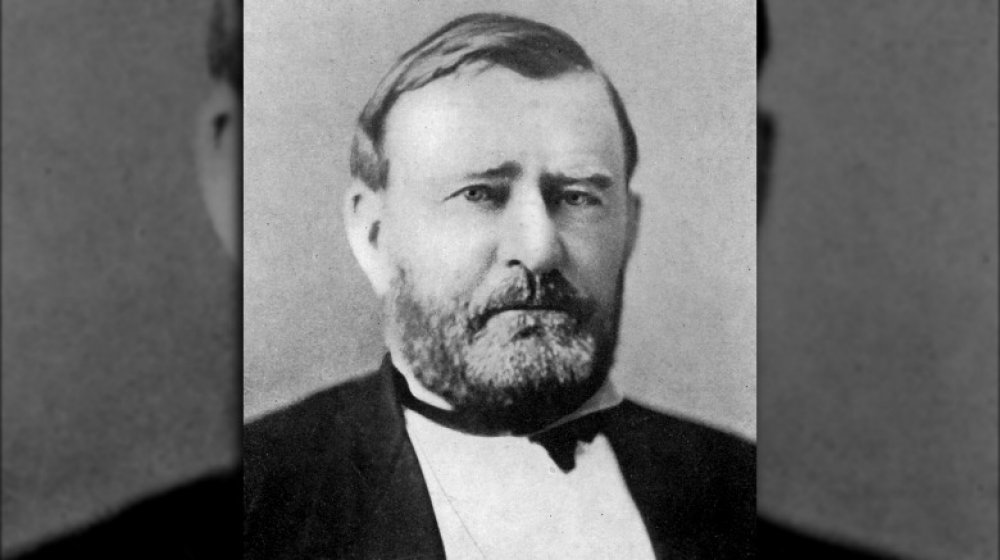

The Untold Truth Of Ulysses S. Grant

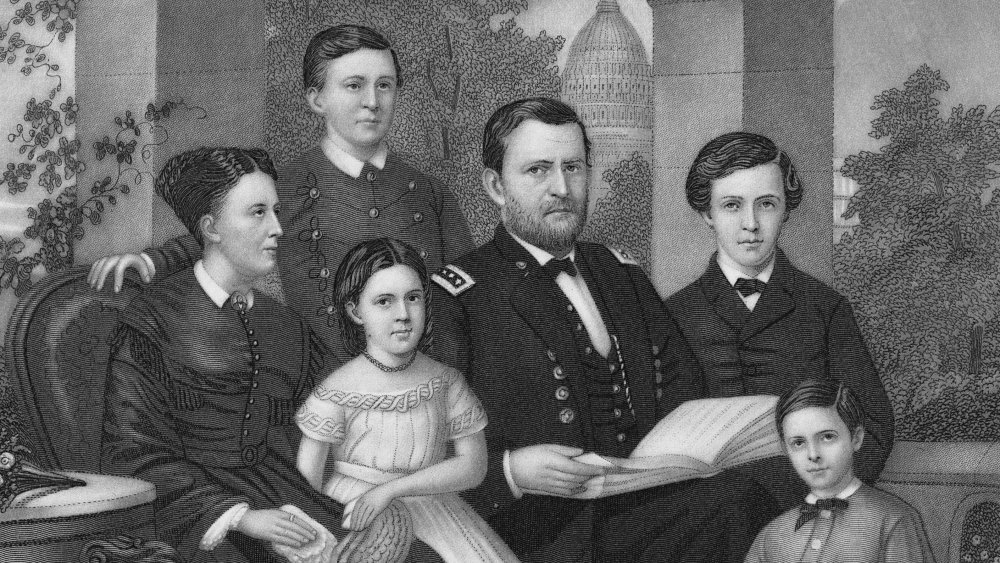

Ulysses S. Grant should be a lot more famous than he is. Despite being the face of the $50 bill and one of the most successful generals in United States history, not to mention serving two terms as our 18th president, Grant just doesn't get much love in the modern age. His name mainly comes up during discussions about greatest generals or worst presidents.

The untold truth of Ulysses S. Grant (first truth bomb: The "S" doesn't stand for anything. It was a typo that stuck) is a much richer and more fascinating story than simply "genius tactician" or "incompetent president." Grant was a man who struggled in one way or another his whole life, a man whose professional life was marked by nothing but dismal, grinding failure, with the sole exception of the few years he commanded armies during the Civil War. During that conflict, Grant displayed a mastery of modern tactics that turned the tide of the war and reversed years of ineffective leadership. Proclaimed a hero, Grant's position should have been cemented as one of the most important figures in American history. But once off the battlefield, Grant once again found nothing but frustration.

Grant was a failure before the war

Grant was in many ways a natural soldier. Although a mediocre student at West Point, he excelled on horseback and enjoyed military life. Although Grant wasn't particularly committed to a military career and planned to resign once his initial term of service was up, he did well as an officer. He served with distinction in the Mexican-American War and showed a flair for organization through a string of assignments afterward.

As author Ron Chernow notes, however, after his arrival at Fort Humboldt in California, boredom and conflict with his new commander drove him to drink, and he was forced to resign in disgrace. With a young family to support, Grant had to pursue a living, and it did not go well at all. As PBS recounts, Grant moved his family to Missouri, where he bought a farm he named Hardscrabble. The name fit — the Grants struggled to survive. Grant's investments failed, and his attempts to launch careers went nowhere — at one point he was reduced to selling firewood in the streets. As Chernow notes, his father came to get him and the family, concluding that he had "no business qualifications whatever."

Grant took a job as a clerk in his father's leather goods store in Galena, Illinois. He wasn't particularly good at that, either.

Grant was probably an alcoholic

Ulysses S. Grant was dogged by rumors about his drinking his entire adult life. He resigned from the Army in 1854 after being caught inebriated while on duty, and rumors of his drinking kept him from any sort of meaningful commission in the early days of the Civil War despite his experience (and success) during the Mexican-American War. The word "alcoholic" was never used about Grant at the time — but that was because alcoholism as a disease wasn't recognized at the time. People who drank too much were generally considered weak and unreliable.

As The Washington Post notes, a complicating factor in discussing Grant's drinking was its episodic nature. He would go months or even years in perfect sobriety and then indulge in drinking binges — which could be rather epic. In fact, Grant's drinking was even brought up during his most successful service in the Civil War. Instead of denying it was a problem, President Lincoln reportedly fell back on practicality, saying "I can't spare this man. He fights."

Grant always denied drinking when he was on active duty in the field, and his honesty about his relationship with alcohol backs up this claim. As Ron Chernow notes, Grant openly admitted he had a problem with alcohol and took a pledge at an early age to resist the temptation — not the actions of a man seeking to cover up his weakness.

Grant struggled to get a command

When the Civil War erupted, Grant should have been an obvious choice for a high-level posting. He was experienced and had served with distinction. Back in the mid-19th century, the country had only a very small standing army, and many states and localities raised regiments on their own. According to Ron Chernow, despite a losing streak that saw his farm and business endeavors fail, he could have had command of a small group of soldiers right away. But he regarded a mere captain's rank as beneath his experience and held out for something grander.

For a while, this seemed like it would be another failure in Grant's life. Volunteer regiments were raised, and Grant patiently waited for the call to lead, but none came. As The New Yorker notes, his reputation for problematic drinking was a major problem. When he was finally offered a staff role, he despaired again, as he was confined to the back office, writing reports and organizing supplies. Slowly, his talent for military matters made him impossible to ignore, and Grant was finally granted command of the 21st Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

His troops were initially unimpressed. Grant's recent economic hard times showed when he arrived in tattered civilian clothes instead of a resplendent new uniform. But it wouldn't be long before he proved his worth on the battlefield.

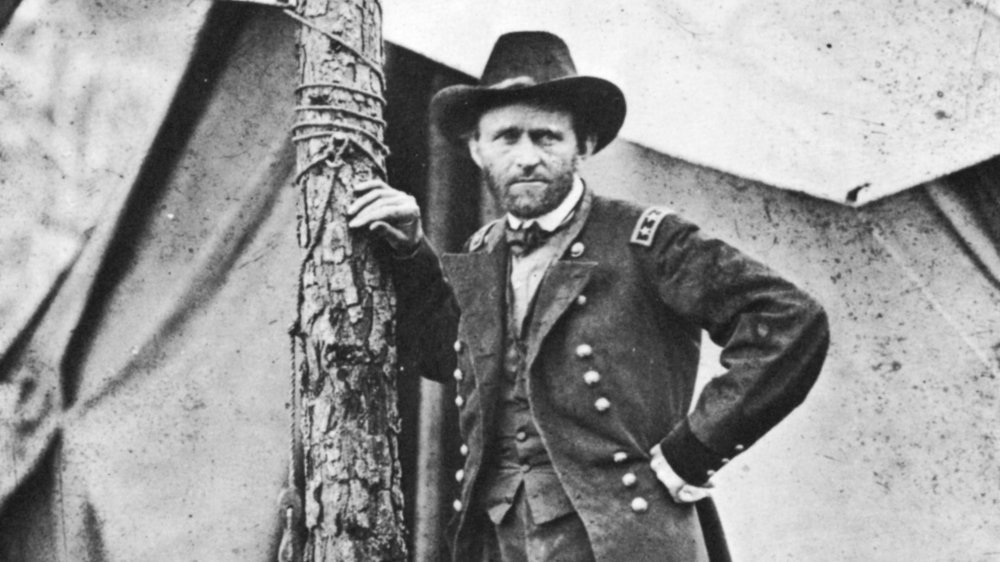

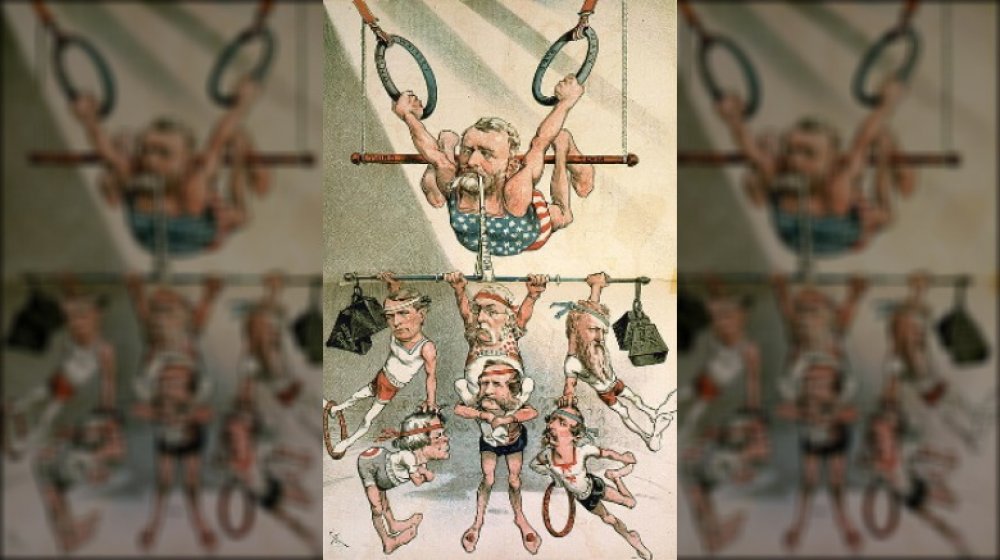

Grant was a military genius

The one arena in which Ulysses S. Grant was undeniably a genius was warfare — but for a long time, even this recognition was denied him. Although revered as a hero for decades after the Civil War ended, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, an effort to revise history, known as the "Lost Cause" movement, strove to malign Grant as a "butcher" who only won his battles because he could afford to lose many more soldiers. As The Washington Post reports, this effort positioned Confederate General Robert E. Lee as the true genius of the war, a man leading noble and chivalrous men with intelligence and genius, only to be overwhelmed by the brutal use of superior numbers.

But this simply isn't true. As West Point's Modern War Institute notes, Grant is considered by modern military historians to be the first commander to understand the power of joint operations — of having different segments of the military working together in a coordinated fashion. He was also the first general to understand that warfare had changed from a slow, seasonal event to a year-round campaign that sought to leverage "total war," the infliction of damage to an enemy's economy and infrastructure. As the Smithsonian's senior historian David C. Ward notes, Grant had a much more difficult job than Lee, because he was supervising the entirety of the North's war effort, including large armies under the command of other generals. No wonder his innovations and tactics are still taught today.

Grant was supposed to be with Lincoln when he was assassinated

The assassination of President Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth is one of the most infamous moments in American history. Despite the fact that every kid learns about it in school, most don't realize that Lincoln wasn't the only name on Booth's list. As Smithsonian Magazine reports, the National Republican newspaper reported that Grant and his wife would be joining the Lincolns at Ford's Theatre that night. Booth saw an opportunity to murder not one but two of the men he blamed for the defeat of the Confederacy, not knowing that Grant had begged off and decided not to attend.

But what's truly incredible is that, according to author Ron Chernow, Boothe and Grant crossed paths that evening. As the Grant family rode in a carriage down Pennsylvania Avenue, they were menaced by a "dark, pale man" on horseback who galloped by their carriage several times, glaring into it. Later, they realized this had been John Wilkes Booth himself, apparently enraged that one of his targets was slipping away.

Later on, riding the train out of Washington, someone tried to enter Grant's private car, and he received an anonymous letter weeks later from a man confessing that he'd tried to assassinate him but had failed, and was glad he had. If Grant had given in to political pressure to hang out with his boss, he might have died — or saved the day. We'll never know.

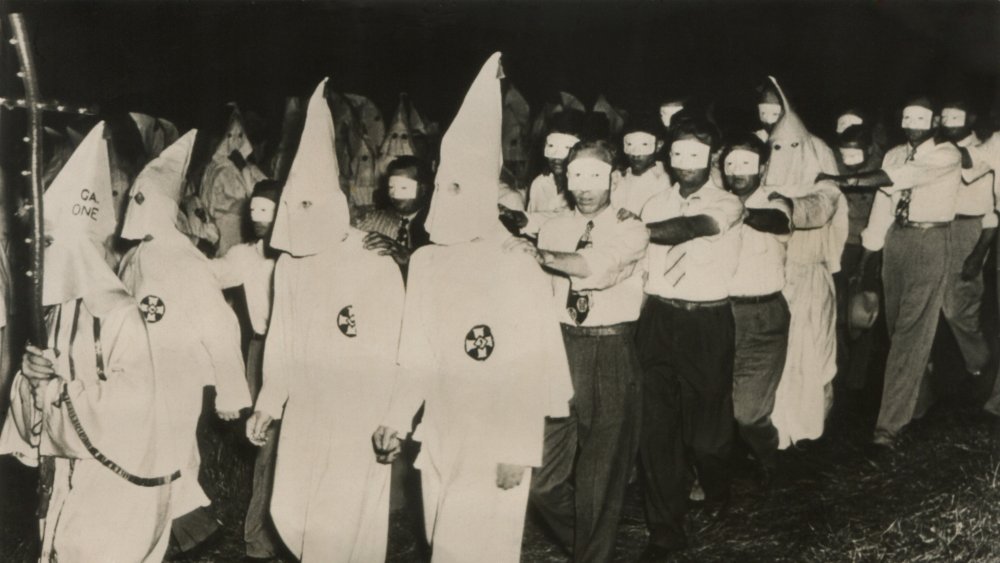

Grant almost destroyed the KKK

Grant had plenty of failings, but at his core, he was a good man. Although never a passionate abolitionist (his wife, Julia, came from a Southern, slave-owning family), his anti-slavery stance was clear long before the Civil War thrust him into the thick of it. So it shouldn't be surprising that whatever other failings he displayed as president, coddling racists wasn't one of them.

As The Guardian reports, Grant was a fervent believer in the power of the vote. He was convinced that once the freed slaves were able to vote and exercise political power, they would gain equal status in society. But the terrorism that rose up in the South in response to the newly freed former slaves taking part in the political process was surprising in its ferocity and blatancy — the recently formed Ku Klux Klan burned buildings, openly murdered black citizens, and worse.

Grant didn't hesitate. As Ron Chernow details, he pushed Congress to give him the authority and firepower to do something about the KKK — and once he had these things, he moved decisively. Federal troops moved in and arrested many Klansmen, and the courts issued harsh sentences. Grant ignored complaints from local authorities that he was overstepping his authority, and by 1872, the KKK had been almost completely wiped out across the South. It would be decades before a new form of the terrorist organization would rise up again.

Grant was a failure after his presidency

Ulysses S. Grant's life story is one of incredible success combined with almost inexplicable failure. After his early attempts at business failed, he was saved from poverty when the Civil War gave him a second shot at military glory. He traded on that glory to ascend to the presidency of the United States, the youngest man to ever do so at the time. And as PBS reports, after his two tumultuous terms in office, he and his family embarked on a world tour. Grant was possibly the most famous man in the world after Abraham Lincoln at the time, and he was greeted with crowds of admirers wherever he went.

When he returned to America, he naturally sought to ensure that he never descended to the depths he'd seen before the war. He was convinced by his son, Buck, to invest all of his money in an investment firm he co-owned on Wall Street in New York called Grant and Ward. Grant was dazzled by reports of huge gains on his investments and became confident that he was a millionaire who could retire to a life of ease.

But, as Ron Chernow writes, Buck's partner, Ferdinand Ward, was secretly embezzling money from the bank, which failed spectacularly on May 6, 1884, leaving Grant penniless.

Grant hated his father-in-law

People not getting along with their in-laws is a tale as old as marriage itself. But for Ulysses S. Grant, it was a particularly trying story. He met the love of his life, Julia, when his schoolmate at West Point brought him home to the Dent family farm. Julia's father, Frederick Dent, was wealthy and extremely loyal to the South and a way of life built on slavery. He also, according to Ron Chernow, opposed his daughter's romance with Grant from the very beginning.

Dent's main objection to Grant as a suitor to his daughter was money: He was an aristocratic snob and believed that Grant's military career would never give his daughter the sort of life she deserved. He withheld his permission for the two to marry for years as a result, and even after the marriage, Grant's parents hated the Dents and vice versa, causing Ulysses and Julia endless trouble.

The final irony, according to Smithsonian Magazine, is that Frederick Dent was actually a terrible businessman himself, and after running the family farm into the ground, he had to come to his son-in-law for help, suddenly forgetting his politics and his opinion of the man. Grant saved his in-laws, causing himself a lot of financial strain, and was never properly thanked by his father-in-law, who refused to admit any sort of error on his part.

Grant died broke

After his son's bank — in which he'd invested all of his money — failed in 1884, Grant lost about $100,000. He was flat broke. But according to Investopedia, which lists Grant as one of the poorest US presidents, Grant had been living beyond his means for years before that, leaving him particularly vulnerable to this sort of financial disaster. According to History, the Grants had a total of $210 to their name. When word got out that the war hero and former president was in dire straits, strangers mailed him money — which he gladly accepted.

Famous author Mark Twain had been pushing Grant to write his memoirs for years, but Grant, an unassuming man, had little interest in doing so. When Grant was diagnosed with terminal cancer later that year, however, he realized he was very close to leaving his wife and family absolutely nothing. He accepted Twain's offer, and CBS News reports he received $50,000 and the promise of an incredible royalty rate of 75 percent. Frail and weak, Grant attacked the project with typical industry, writing more than 350,000 words in under a year. Twain was impressed with how well Grant wrote, and advance word saved the day: By the time Grant finished the manuscript, there were 100,000 pre-orders for the book. In the end, Grant posthumously earned over $400,000 from his memoirs (millions in today's money).

Grant's love of cigars killed him

Grant was a man of few vices, but he indulged in the vices he did have with enthusiasm. According to Ron Chernow, as a younger man, Grant was a pipe-smoker. After one of his early victories in the Civil War catapulted him to national fame, a report that he was spotted holding a cigar prompted people all over the country to send him boxes of expensive cigars. Grant took to the new vice, and according to The Inquirer, Grant was soon smoking 20 cigars a day — and chewing an unlit cigar when he wasn't actively smoking one.

The year 1884 proved to be a terrible one for Grant. In May, his investment in his son's bank collapsed, leaving him bankrupt. A few months later, he started to experience pain in his throat and was diagnosed with throat and tongue cancer. The prognosis was terminal.

According to CBS News, Grant's death was slow and agonizing. He soon found swallowing painful and began to lose weight as eating became nearly impossible. He was given morphine shots, and his throat was swabbed with cocaine (yes, cocaine) to give him some relief. After a lifetime of smoking dozens of cigars daily, he died on July 23, 1885.

More than a million people attended Grant's funeral

In some ways, Grant is a forgotten president today, but when he died in 1885, he was incredibly famous — and popular. In fact, according to The Washington Post, more than one million people attended Grant's funeral in New York City on August 8, 1885. That's more people than came out to mourn Abraham Lincoln in 1865, demonstrating just how popular Grant actually was, which is remarkable considering that his presidential administration was marred by corruption and scandal, and the last year of his life was rocked by a financial scandal that ruined him.

What's even more remarkable, as PBS notes, is that Grant's popularity extended to his former enemies. Among the pallbearers carrying his coffin in New York were former Confederate generals Simon Bolivar Buckner and Joseph Johnston. They walked beside Union generals William T. Sherman and Philip Sheridan, and more Confederate soldiers were among the official mourners.

Grant was so popular that people from all over the world donated money to build the mausoleum that holds him and his wife, Julia, in Morningside Heights. A million more people, including President William McKinley, attended the tomb's dedication when Grant's body was moved there in 1897. Time was not kind to Grant, however. Southern sympathizers recast him as a butcher, and modern historians ranked his administration near the bottom, eroding his stature.

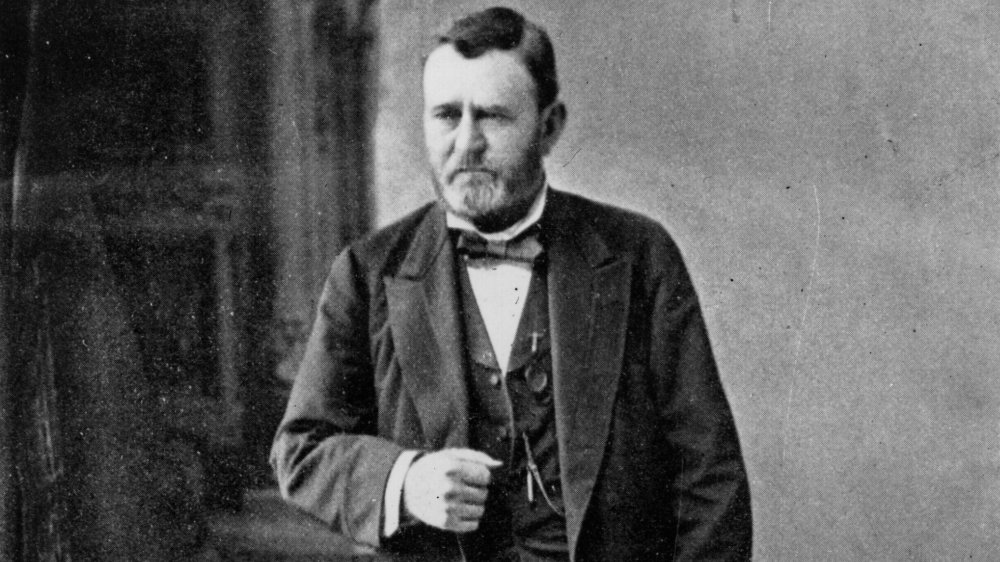

Grant is widely considered one of the worst presidents

When Ulysses S. Grant was elected president in 1868, expectations were high. Grant was a military hero and genius, the man who had finally organized the Union armies and defeated the Confederacy. He was known to be an honest and hardworking man who was obviously capable of directing the efforts of huge, complex bureaucracies, as well as someone used to being in charge. There was a sense that Grant would bring a high level of ethics and ability to the office.

This sense was very quickly proved wrong. As The New Yorker notes, Grant's presidency is still considered one of the most scandal-ridden and corrupt in US history. What's truly tragic about this is that Grant was in no way corrupt himself. One of the reasons the president died nearly broke is the fact that he was never one to profit illegally or unethically.

But as Time makes clear, Grant was guilty of poor judgment. One of the biggest scandals of his administration, the Crédit Mobilier Scandal, actually dated back to 1867, two years before he took office. But almost everyone Grant appointed to his administration, including his vice president, were implicated in this massive bribery scheme. As US News points out, Grant was aware of his own failings, once saying, "My failures have been errors of judgment, not of intent."