The Untold Truth Of Steve Martin

Oftentimes, comedians — and their comedy — just don't have longevity. What was funny in 1960 might seem dated or tone-deaf in 2020, and it can be tough to find routines that translate across the generations. Every so often, though, there are funny men and women who appeal to everyone from Boomers to Gen Z, and with the release of "Only Murders in the Building," Steve Martin has proven that he's just as hilarious in 2021 as he was when he was a Wild and Crazy Guy.

Martin has always been the funny guy, but he's also been reinventing himself pretty regularly — and so well that it's easy to overlook. Go back to 1981, and he was selling out stadiums when he decided stand-up just wasn't his thing, and he was going to see what else was on the horizon. That's pretty admirable: Walking away from massive success takes a lot, but when Martin spoke with AARP — a testament to his longevity — he revealed the fact that loud, smoky, seedy clubs were never really his scene anyway.

Famously moving on to acting and writing, Martin hasn't just found success, he's found a special place in the cultural landscape of countless people. (What, after all, is Thanksgiving, without "Planes, Trains, and Automobiles" playing as the family gathers around the television?) Arguably even more important? He described his life to AARP: "Very, very happy. I mean, it's actually the perfect shape of a life." Exactly how he got there is a fascinating tale.

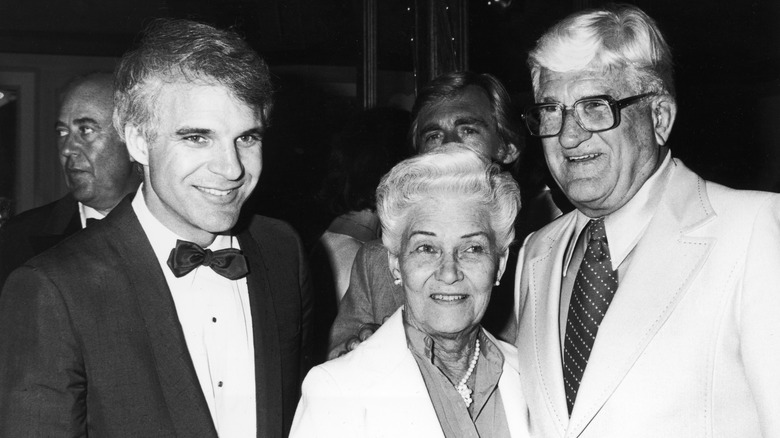

He had an odd relationship with his father

In his memoir, "Born Standing Up: A Comic's Life," Steve Martin recalled never calling his father anything along the lines of "Dad," and instead, he was always just "Glenn." That distance was characteristic of their relationship, and he wrote, "When I was seven or eight years old, he suggested we play catch in the front yard. This offer to spend time together was so rare that I was confused about what I was supposed to do. We tossed the ball back and forth with cheerless formality."

At the same time, though, he recalled his father as always generous, lending money to friends in need and making sure his comic book subscriptions were always paid. Clearly, his father loved him, but why was he always so standoffish and angry?

Over the years, Martin found his own observations coalescing into some kind of understanding about what was going on with his father, and he says that it was summed up when the elder Martin gave his opinion of his son's now-classic film, "The Jerk." "My father chuckled and said, 'Well, he's no Charlie Chaplin.'" Born in Texas, they'd moved to Hollywood in order to help Glenn pursue an acting career. It didn't take off, and Martin suspected that there was always more than a bit of lingering resentment there. When his son became the star? Ouch.

He started working at Disneyland when he was 10

In 1955, Steve Martin scored his first job — and honestly, it's pretty much a dream job. In his autobiography, "Born Standing Up: A Comic's Life," he shared the story of how he got a job at Disneyland during the very first summer it opened. He wrote of how his 10-year-old self pedaled his bike off to Disney, and was put to work selling guidebooks for 25 cents — two of which he got to keep.

"The two dollars in cash I earned that day made me feel like a millionaire," he recalled, and perhaps more important than the work experience was the experience that came afterward. By the afternoon, everyone had bought their guidebooks, but Martin had the run of the park for the rest of the day — and he made the most of it.

At Merlin's Magic Shop, he learned the sleight of hand tricks that he worked into his stand-up, and at Frontierland, he learned rope tricks (that he would later get a job demonstrating). And at Pepsi-Cola's Golden Horseshoe Revue, he saw his first stand-up comedian, Wally Boag. "Here I had my first lessons in performing, though I never was on the stage. ... My fantasy was that one day Wally would be sick with the flu, and a desperate stage manager would come out and ask the audience if there was an adolescent boy who could possibly fill in," he reminisced.

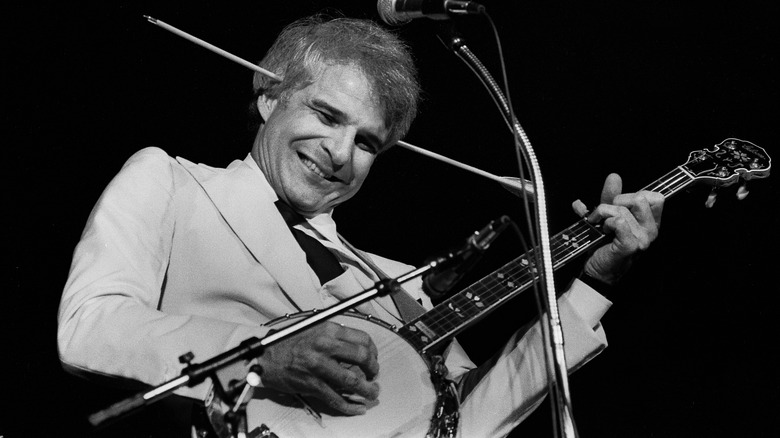

Here's what made him pick up the banjo

Not only is Steve Martin a comedian, but he's pretty amazing at playing the banjo, too. In an interview with Fuse, Martin explained that the love went back to his teenage years. "I heard it, and that was enough for me," he said. He was inspired by a folk music movement spearheaded by groups that included the Kingston Trio, and needing to know how to play, he became determined to teach himself — so, he did.

With the help of some books and a record player — which he slowed down in order to hear and learn the music one note at a time — he found that it turned out to be a really handy skill. When he started doing stand-up, he had a certain amount of time he had to fill, and when he didn't have quite enough material ready and waiting to go, it was the banjo to the rescue.

Even when he became more established, he said that he kept the banjo because he wanted everyone to know that he could do something that most people might think was hard, although he didn't really find it that. "I can't tell you if it was hard, because I didn't have anything to compare it with," he explained to NPR. But it looked hard, and that was good enough.

His Troubador-era name-dropping is wildly impressive

Everyone's got to start somewhere, but for Steve Martin, the early days he described in his memoir, "Born Standing Up: A Comic's Life," read like a who's who of the era's pop culture landscape. By the time Martin was in his 20s, he was performing across the country and opening for some pretty big names. One of his go-to places was the Troubadour in Los Angeles, where he rubbed elbows with everyone from Joni Mitchell to Michael Nesmith of The Monkees. He recalled opening for Linda Ronstadt, telling PBS, "She was one of the most potent live talents you ever saw. She wore a silver lamé dress that was cut so short you couldn't believe it. She wore no shoes and had that great, great voice."

Also there? Elton John, Richard Pryor, and David Geffen, who scouted countless musical acts there — and that included an up-and-coming Glenn Frey. At the time, he was performing as a part of the duo Longbranch Pennywhistle, and looking ahead to his next band.

Martin recalled Frey asking him what he thought of the name he had in mind, but the conversation didn't go entirely as he'd probably hoped. "He'd say, 'What do you think of this name? Eagles?' I'd say, 'Yea, the Eagles. That sounds great.' He goes, 'No, Eagles.' I say, "Yeah, the Eagles. That really sounds good.' 'No, Eagles.' I went, 'Eagles!'"

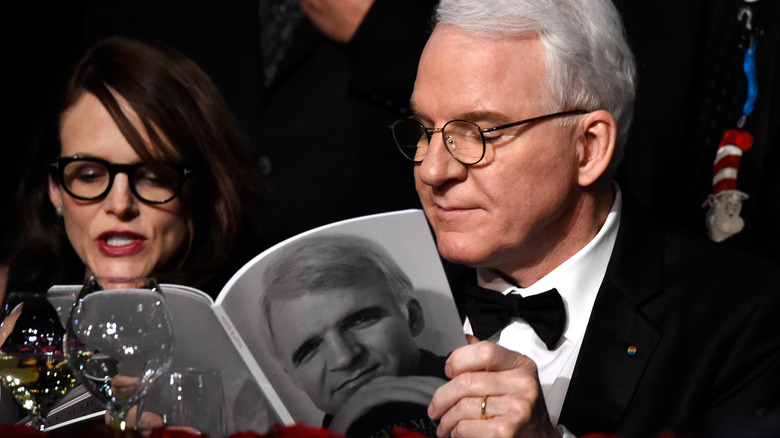

Steve Martin + Martin Short = Wholesome

The decades-long friendship between Steve Martin and Martin Short is downright wholesome, and when the two went on The Tonight Show in 2016, they discussed their friendship. They had never met before filming "Three Amigos," they revealed, and when Short stopped by Martin's house, he was in awe. He said, "I walked in, and it was like, so beautiful. There were Picassos on the wall, and Hoppers, and I said to him, 'How did you get that rich? Because I've seen your work.'"

The seeds of friendship were planted, and in an interview with The Guardian, Short explained, "You know, you make movies and you're in each other's lives for a few months, in Yugoslavia or wherever, and then you never see each other again. But Steve and I made each other laugh ... That created a determination to see each other, and then have dinner, and that evolved into taking family vacations together."

And it had — for more than three decades by the time of that interview. Bizarrely, though, Martin had no idea that "Three Amigos" had seen such enduring popularity. When they appeared on The Howard Stern Show in 2021, Martin revealed that he had been a little bummed when the movie came out and did "fine." When he got a call from Empire wanting to do a "Three Amigos" cover shoot for the 25th anniversary, though, he was blown away by the longevity of it.

He avoided the drugs that consumed so many of his colleagues

Drugs and alcohol fueled the comedy and music scene of the 1970s, but Steve Martin says that he was never a part of it. In his memoir, "Born Standing Up: A Comic's Life," he recalled being on his way to see a movie with some friends, smoking some pot (which he described as "a dietary staple"), and having a terrifying experience: "I felt my mind being torn from its present location and lifted into the ether. My discomfort intensified, and I experienced an eerie distancing from my own self that crystallized into morbid doom. I mutely waited for the feeling to pass. It didn't ..."

The rest of the night was equally terrifying, and he recounted feeling his heart racing and his sneaking suspicion that he was having a heart attack. It was so bad that he thought about going to the hospital, and when he tried to explain what had happened the next day, he found himself living through it again. It was only later that he learned it hadn't been a heart attack, but an anxiety attack.

Martin explained to NPR that he came to see the experience as a good thing: "What it did was it kept me from drugs ... I couldn't take aspirin, I was so afraid of this event happening again ... it kept me from ... the scourge of cocaine, which was common — and never took LSD, never took anything after that."

Working with John Candy was one of the high points of his career

Ask almost anyone about their list of classic movie comedies, and "Planes, Trains, and Automobiles" is on the list. (If not, it's time for a serious conversation.) It's made even better with the knowledge that behind the scenes, Steve Martin really was having the time of his life. He spoke with USA Today for the film's 35th anniversary, and reflected that the only sad thing about it was that neither John Candy nor John Hughes lived to see the long-lasting popularity it gained as a holiday favorite.

"We laughed a lot," Martin recalled of his time with Candy. "But we did the laughing part before rolling to get that out of our system as we'd work out what we were going to do. ... We were comfortable with each other, we liked each other. He would make me laugh."

Candy's character is the sort of helpful that just never results in anything good happening, and it's all the more heartbreaking — and hilarious — to know that it all comes from a genuinely good place. Martin has said that there's plenty in the movie that was ad-libbed on-set, and one of those things that came from Candy was the film's big reveal near the end. In Nick Semelyen's "Wild and Crazy Guys: How the Comedy Mavericks of the '80s Changed Hollywood Forever," (via Express), Martin shared that even as the years passed, he still tears up at the scene.

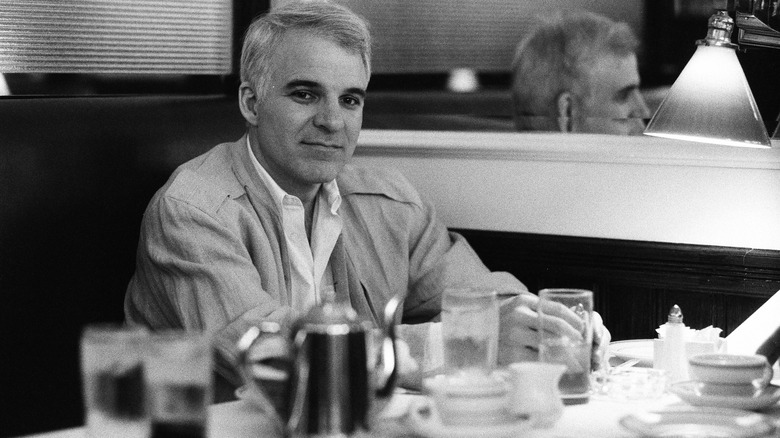

Being funny doesn't come naturally to him

Steve Martin might make comedy look like it's the most natural thing in the world for him, but surprisingly, it's not. When he spoke with NPR about his career in stand-up, he noted that although he'd had some serious success on-stage, those four years were the product of 14 years of developing his act. It's no wonder, then, that he observed in his memoir, "Born Standing Up: A Comic's Life," "Thankfully, perseverance is a great substitute for talent."

There were times when his careful preparation proved to be not exactly an asset, and he recounted one appearance on "The Merv Griffin Show," where a bit about buying a Greyhound bus went very, very badly. Griffin asked him why it was a bus, and he recalled his horror: "I had no prepared answer; I just stared at him."

In 2022, The Hollywood Reporter did a piece on Martin, and when they talked to Martin Short, he recalled getting a phone call from his old friend, asking if he'd mind listening to a few ideas: Why? He'd been invited on Jimmy Kimmel's show ... and it was two months away. "'And you're already working on it?'" Short recalled marveling. "That's why he's Steve Martin. That's why he's still Steve Martin."

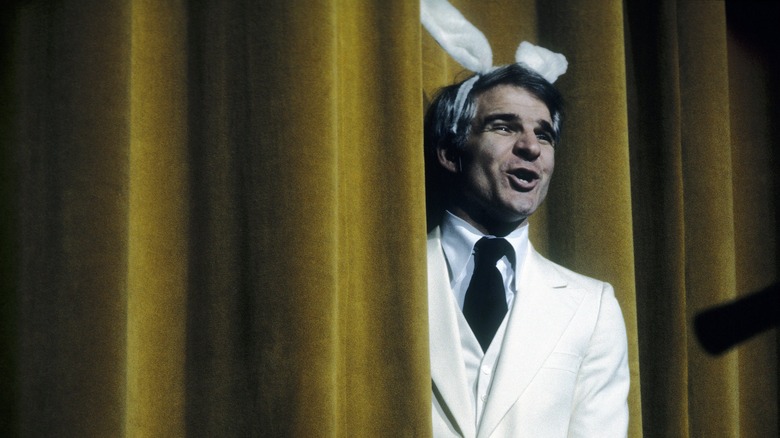

Here's why he retired from stand-up

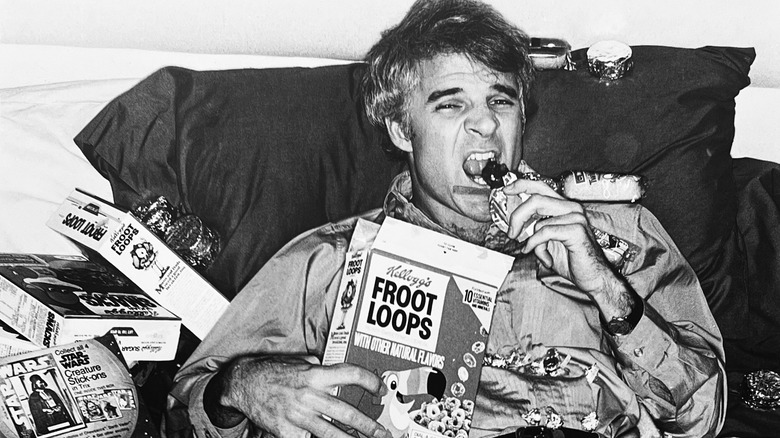

Steve Martin walked away from an incredibly successful stand-up career, and from the outside, it's easy to wonder why on earth someone would give that up. In his memoir, "Born Standing Up: A Comic's Life," he shared stories of grueling schedules on the road, room-service dinners, and some shocking numbers, including performing in 85 different cities in just 90 days.

He explained there was a lot going on, including the exhaustion. The material was always the same, and there was no room for changing it when he had 40,000 people in an audience, all waiting for laughs. Now that he'd made it, everyone knew him — and that meant he suddenly found himself needing a security team and escorts when he went from hotel to theater to hotel ... and back again. "I experienced a concomitant depression caused by exhaustion, isolation, and creative ennui," he wrote. "I no longer had normal access to civilized life."

He was booked out years in advance, and then there was the show that made him realize that he was done. When his heart started beating erratically during a 120-degree show, he headed to the hospital. "Confident that I was dying, a nurse asked me to autograph the printout of my erratic heartbeat," he wrote. "I was becoming, like the Weinermobile, a commercial artifact."

He was caught up in an art fraud scandal

Steve Martin is pretty famously an art collector, and it was a 20th-century piece reportedly painted by Heinrich Campendonk that had his name mentioned alongside a phrase collectors dread: "art fraud." In 2011, Der Spiegel reported on one of the largest art fraud cases in recent history — and one of the paintings was once in Martin's collection.

The work was "Landschaft mit Pferden," or "Landscape with Horses," and Martin bought it from a French art gallery. The price? A whopping $850,000. It turned out that it wasn't authentic at all, but it was a good enough forgery that it fooled some major experts. Martin sold the painting a little over a year later and took a massive loss: It wasn't until after the sale that it was linked to a ring of art forgers who had successfully mimicked the work of other artists and fooled scores of experts.

Martin spoke to The New York Times after word got out, saying that it wasn't the first time he'd bought forged artwork. "Each time you become more and more cautious," he said. "You always have to guard against it. The fakes were quite clever in that they gave it a long provenance and they faked labels, and it came out of a collection that mingled legitimate pictures with faked pictures." And it just goes to show — sometimes, even the experts are wrong.

He's overcome severe hypochondria

It's no secret that the experiences of childhood shape us in adulthood, for better or for worse. For Steve Martin, an incident that happened at Disneyland's Golden Horseshoe changed his way of thinking for years, and it's terrifying stuff. In his autobiography, "Born Standing Up: A Comic's Life," he wrote that he had been listening to a stand-up comic performing there when he suddenly blacked out. He was later diagnosed with what the doctor told him was a "prolapsed mitral valve," and that's a scary thing for a kid to hear. It's a condition more commonly known as a heart murmur, and as the Mayo Clinic says, it's rarely a problem. For Martin, though?

"It planted in me a seed of hypochondria that poisonously bloomed years later," he wrote in his memoir. It wasn't until 2017 — and, somewhat ironically, in an interview with AARP — he revealed that although he had been suffering with it for decades, he'd grown out of it as he got older.

"I worried all these years that I was going to die, and I never did," he explained. "So why waste all that worry? And you know, you absolutely do become wiser — if you're watching and listening."

It took him 15 years of trying to reconcile with his parents

Steve Martin never gave up trying to build a loving relationship with his parents, and he wrote about it at the end of his memoir, "Born Standing Up: A Comic's Life." It started, he said, when a good friend lost his parents to a tragic accident and a suicide, and warned Martin not to take the days for granted. For 15 years, he made it a point to spend at least the weekends with them.

Martin recalled going to lunch one afternoon, and hearing his father say those oh-so-special words — "I love you." — just once. It wasn't long afterward that it was time to say goodbye, and Martin recalled his father being ready to pass, but regretful: "For all the love I received and couldn't return," he said. Then, he recalled crying: "We wept for the lost years."

His mother's health went downhill not long after his father passed, and Martin recalled dealing with the dementia that gripped her. During her lucid moments, she would apologize for not sticking up for him more as a child, and when it came time to say goodbye, he recalled, "She said, 'I wish I had been more truthful,' a comment regarding, I believe her lifelong subordination to my father. [Then], she expressed embarrassment that she was dying, saying, 'I hate to be silly.'"