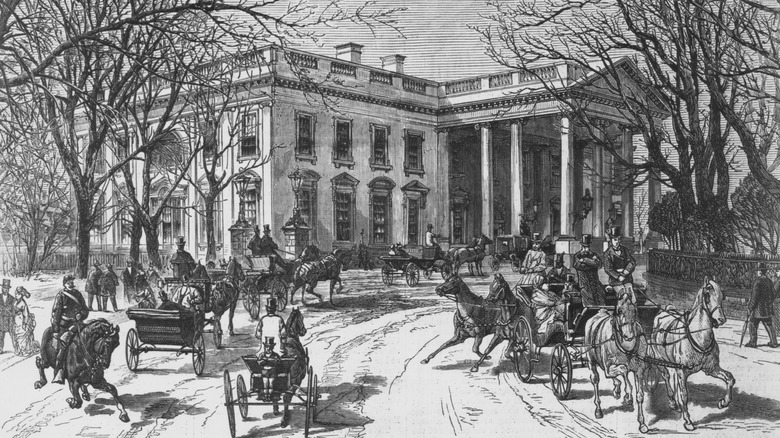

How George Washington Picked The White House's Location

George Washington never set foot in the White House. The Residence Act that called for the creation of a new capital city was passed in 1790, at the dawn of Washington's administration, but he retired in 1797 and died two years later, one year shy of the 1800 deadline set for the capital's completion. Nevertheless, Washington still had a heavy hand in the city's development — and in the placement of the president's mansion.

The Residence Act empowered Washington, as president, to set Washington D.C.'s location. He also decided where the Capitol building and the White House would be placed within the district. The president's placement physically and symbolically connected the two buildings via what we now know as Pennsylvania Avenue. The three commissioners who managed D.C.'s construction were personally selected by Washington, as was the White House architect James Hoban.

As president, Washington personally oversaw the development of the White House and D.C. as a whole and continued to monitor progress even after retiring from public life. He even acquired lots to build housing in D.C. before he died and encouraged development between the Capitol and the White House to spur the growth of the city.

The White House - and D.C. - were located by compromise

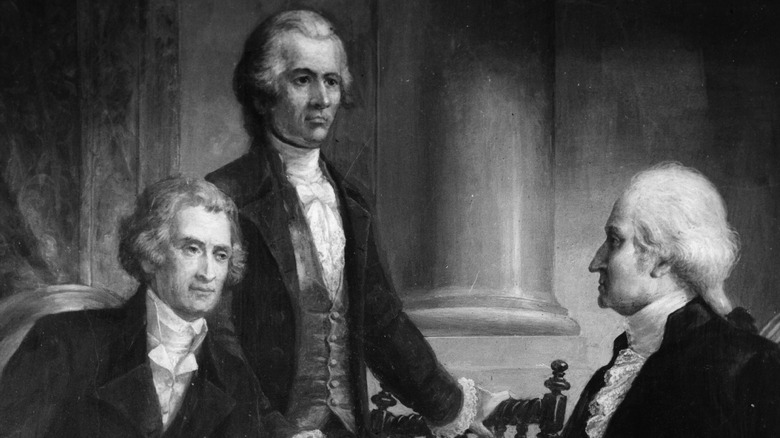

As part of Washington D.C., the White House was placed where it is — along the Potomac River — due to political compromise. Known as the Compromise of 1790, it was the first of several attempts to reconcile northern and southern interests in the decades before the Civil War. It has often been framed as an appeasement of southern slaveholding interests, as it was by Mount Vernon. When George Washington's administration began, the nation's capital was in Philadelphia, and according to PBS, prevailing sentiment at the time was for permanently fixing the seat of government in the north. Prominent southerners like James Madison feared the potential loss of influence for their region of the country — and the growth of antislavery sentiment. By placing the capital in the south, it was thought, there would be an implicit acceptance of the institution.

In fact, there were other issues animating the capital debate. Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and others opposed Alexander Hamilton's scheme of strengthening the federal government by assuming state debts, which would also empower financial speculators widely seen as corrupt. After months of negotiations and the famous dinner hosted by Jefferson, Madison and Hamilton reached a compromise: Support for Hamilton's financial scheme for a relocated capital, and a reduction in Virginia's tax obligation. Per the National Constitution Center, Washington, a southerner himself, enthusiastically supported moving the capital closer to home, and from the compromise followed the Residence Act.

George Washington was long interested in the Potomac's potential

George Washington had longstanding interests in the Potomac River. His own estate of Mount Vernon was located on its banks, on land held by his family since 1674. The Potomac held the home of Washington's heart, and during his adventures before and during the French and Indian War, he came to appreciate its importance to the expansion of America into the west.

Per Mount Vernon, Washington saw the development of the Potomac as an economic and political good. If it could be connected with the James and Ohio rivers (the latter feeding the valley where Washington snapped over 20,000 acres himself), it would ease travel and trade within the United States while undermining temptations to engage in commerce with bordering British and Spanish territories. Washington helped establish the Potomac Company to undertake the often dangerous work of building the necessary canals and locks, and his interest in the Potomac helped decide the location of the capital and the White House's and influenced his own personal investment in their development.

Philadelphia, the seat of government before Washington, D.C. was established, spent a decade trying to undo the Residence Act. Per the National Constitution Center, the city of brotherly love tried to counter the Potomac with a promised mansion for the president. Washington refused it, stayed in a modest house in Philadelphia, and kept working on D.C. and the White House.