What Would Happen If Washington D.C. Became The 51st State?

Among the political battles of the 2020s is the issue of statehood for Washington, D.C. The inhabitants of the District of Columbia, which is under federal purview, have argued that despite paying federal taxes and fulfilling duties such as military service, they are denied congressional representation. Their solution is statehood, which proponents — including 39 constitutional law professors at top universities — have argued Congress could accomplish with a simple majority vote.

As is usually the case on Capitol Hill, the situation is not as simple as proponents might like. Among the major issues is whether Congress can make a new state out of Washington, which has a unique status within the nation, without amending the Constitution first. Then there is the issue of whether a reduced federal district would fulfill what the founders had in mind for a seat of government in 1787. Finally, there is the GOP-DNC clash on questions of control of the Senate. But, both parties agree, for better or worse, D.C. statehood could certainly change the fabric of the United States.

The case for D.C. statehood

To understand what would happen after D.C. statehood, it is necessary to understand the stated rationale behind the movement. Although Washington, D.C., is not a state, it functions as one in many respects. The city of Washington has its own school system, mayor, city council, and independent police force — separate from the Capitol Police, which is under federal jurisdiction.

The differences are few but important. The biggest one is that D.C. residents pay federal taxes but do not have representation in Congress. This is by far the biggest gripe in the push for D.C. statehood, harking back to the revolutionary slogan of "no taxation without representation." Since D.C. is majority-minority, the Statehood Commission has argued that statehood and congressional representation is a matter of racial equality and equal treatment under the law, placing the city's inhabitants on par with those of other states. The city also cited denials of COVID-19 relief, which was given to states with smaller populations than D.C., such as Vermont and Wyoming. The inhabitants of D.C. are overwhelmingly in favor of statehood. A 2016 referendum registered an 86% supermajority in favor.

D.C. would not simply be converted into a state

The entire debate on D.C. statehood is a bit of a misnomer. Although the jury is still out on its constitutionality, Republicans and Democrats agree that the District of Columbia cannot simply be converted 1:1 into a state the way Puerto Rico, for instance, could be. For this reason, the current D.C. statehood plan does not call for doing so, although that is the impression one might get from current debates.

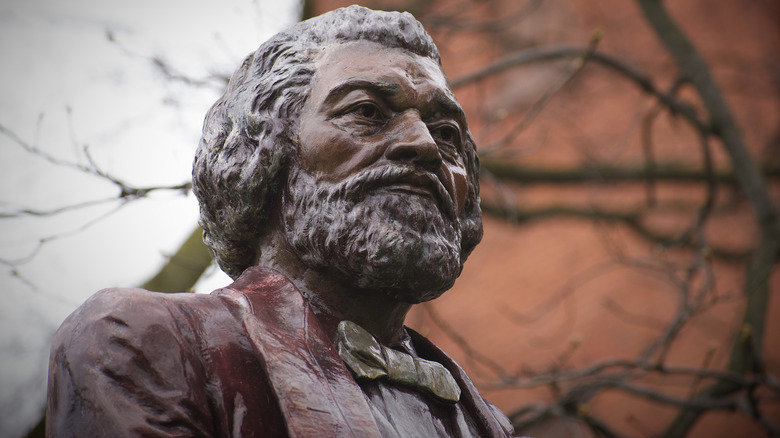

Despite the misleading nomenclature and rhetoric coming from both sides of the debate, the actual plan proposes carving out a whole new entity from the federal District of Columbia. Because Article I, Sec. 8 of the Constitution requires that Congress and the federal government have a seat of government reserved unto themselves of no more than 10 square miles, D.C. cannot be simply converted into the 51st state wholesale. Instead, the plan would reserve 2 square miles of the current District of Columbia to form a new, reduced federal district under Congress' purview, and the rest would be ceded through a majority vote under Article IV, Sec. 3.2 (Congress' power to regulate the national territory) to form a new state called the Douglass Commonwealth, named after famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass. The name would allow the new state to keep the "D.C." designation. This new entity would be completely separate from the District of Columbia as it is known now, which is the exclusive purview of the federal government.

Home rule would end

If the new state of the Douglass Commonwealth was to become reality, it would involve upgrading the city institutions to state-level organs of government. Some of them are straightforward. The mayor of D.C. would become the governor of the Douglass Commonwealth, and the D.C. City Council would convert to a state legislature.

Under the current paradigm, D.C. is under "home rule," which means that while the city council, its mayor, and inhabitants can pass laws, Congress must first review and approve any piece of legislation before it's enacted — something proponents argue is anti-democratic. This power was used in March 2023, when a bipartisan Senate vote and President Joe Biden's signature overruled the city's revision of criminal statutes, which the upper chamber considered soft on crime. If D.C. were to become a separate, sovereign entity equal to the other 50 states, Congress would lose that power while the president would lose the power to appoint district judges, who would likely become elected officials as they are in other states.

The new state would be a Democrat lock

The principal driving force behind D.C. statehood as stated by its proponents is equal representation of the federal district's inhabitants, who pay taxes but do not enjoy full representation or voting rights in Congress. If D.C. were to become a state, its citizens would have two senators and one representative. Republicans, however, have called the process a "power grab," according to the CS Monitor, since the Douglass Commonwealth would be a guaranteed lock-in for Democrats.

The city of Washington is a blue stronghold. It has voted Democrat in every election since 1964 (the first election in which the district had electoral votes), with 92.2% of voters casting their ballots for Joe Biden in 2020. The carve-out state of Douglass would likely follow these trends, although electorally D.C. would be insignificant. It would, however, crucially get two likely Democrat senators. Maryland Democrat Jamie Raskin has called this a major part of D.C. statehood's rationale, since "the Senate has become the principal obstacle to social progress across a whole range of issues" (via the CS Monitor).

Raskin is correct in that the Senate is key to advancing legislation. With its ability to filibuster and the general polarization between it and the House, gridlock has become the norm. Legislation often hinges on one or two votes or the vice-presidential tiebreaker in the Senate. Two new guaranteed Senate seats would give the Democratic Party an extra edge. For this reason, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy called D.C. statehood an attempt by Democrats for more power.

It would raise potential conflicts of interest within a reduced federal district

The 23rd Amendment, ratified in 1961, states that Washington, D.C., as the seat of government, is entitled to the same number of electors equal to the smallest state. Currently, that means three. Generally, electors have to be residents of the state whose vote they are casting in the Electoral College. It is the same for the District of Columbia. Under the current system, finding electors in Washington, a city of nearly 700,000 as of 2022, is easy.

If the Douglass Commonwealth becomes a reality, however, a potential conflict of interest and constitutional issue emerges, as outlined by the Congressional Research Service. The District as the seat of government would be reduced but not eliminated and would simply encompass Capitol Hill and its adjacent offices, the White House, and any other federal buildings. The 23rd Amendment would continue to grant the District those electoral votes.

Article II, Sec. 1.2 of the Constitution states that "no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector." A reduced federal district with three electoral votes granted by the 23rd Amendment would only have a handful of full-time residents, potentially only the president, members of the first family, and a few government officials — none of whom can become electors. To solve this problem, the Constitution needs to be amended.

There would be a push to repeal the 23rd Amendment

Democrats have not dismissed concerns about the 23rd Amendment and have proposed repealing it in response to Republican worries. Sen. Tom Carper's version of D.C. statehood has provided a roadmap for getting there. The plan would repeal the 23rd Amendment through a joint House resolution. The legislation would be expedited through the House, meaning it would placed on the calendar immediately, introduced, and scheduled for a vote within 30 days, avoiding the possibility of dying in committee or on the House floor. The bill would also prevent any debate opposing a vote on the bill and restrict House debate on the bill itself to 10 hours. Any points of order to slow down its passage would be forbidden. In the Senate, it would not be possible to consider any other resolutions until the repeal is voted on.

Were the repeal to pass, the party in control of the presidency would theoretically give up the federal district's three electoral votes. On the face of it, Carper's plan seems a simple, workable solution. But it doesn't mention that repealing an amendment requires another amendment. This, in turn, means that even a Democrat-controlled Congress wouldn't have the power to make it happen, because the states are the final arbiters of what goes in the Constitution, regardless of what either party says.

It's a guaranteed SCOTUS battle

Given the constitutional and historical issues surrounding D.C. statehood and the partisan debate surrounding the effort, it is almost guaranteed that the case of the Douglass Commonwealth would end up before the Supreme Court.

A Supreme Court case would likely address whether the Douglass Commonwealth's existence is constitutional. Proponents of D.C. statehood argue it is. Article I, Sec. 8 of the Constitution gives Congress the ability to resize the federal district. Opponents, however, argue the new state would violate the Constitution's original intent. The American founders, particularly James Madison, intended Washington, D.C., not to be a state to avoid undue influence in Congress.

For opponents, a state completely surrounding the federal district seems like the type of scenario Madison wanted to avoid. Even proponents of D.C. statehood have noted that it would face a strong chance of invalidation on historical grounds from the originalist triad of justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas, and Neil Gorsuch, along with Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.

The court in 2023 is not sympathetic to D.C. statehood, having upheld a lower ruling in 2021 that D.C. residents are not entitled to congressional voting rights. For the case to have a chance, a Democrat administration would have to coincide with SCOTUS openings by adding two more liberal justices to bolster the liberal triad of Elena Kagan, Ketanji Jackson-Brown, and Sonia Sotomayor. Only then would the three guaranteed "no" votes be neutralized.

It would likely trigger popular backlash

While political concerns focus on constitutional questions and control of Congress, ordinary Americans across the spectrum hold other doubts about D.C. statehood. A Gallup poll in 2019 found that 64% of Americans oppose the Douglass Commonwealth, including 51% of Democrats. The widespread opposition, especially among Democrats, is a bit unexpected, considering that 66% of Americans support admitting Puerto Rico -– another likely Democrat lock -– as a state.

FiveThirtyEight has suggested that the reason for opposition to D.C. statehood is that mistrust of the federal government trickles down to the local D.C. level. This hypothesis holds water, considering the data, but it needs further explanation. If the Douglass Commonwealth were a state, it would be the richest in the country, with a per capita GDP of $233,500. The next closest is New York with $96,502. Washington, D.C., and the surrounding suburbs' high incomes are due to a large population of lobbyists, PR professionals, government bureaucrats and workers, federal contractors, and politicians — exactly the types of people Americans distrust.

Americans who oppose D.C. statehood likely fear that the creation of a wealthy, elite-dominated state would risk what James Madison termed in Federalist 43, "[bringing] on the national councils an imputation of awe or influence, equally dishonorable to the government and dissatisfactory to the other members of the Confederacy." In layman's language, the concern is that such a state would be able to rig the federal government and the Constitution in the favor of its power brokers — not D.C.'s poor, but the types of people Americans love to hate.

It would create a fascinating precedent that could backfire on the DNC

Statehood for the Douglass Commonwealth would set a fascinating precedent for other statehood movements in America. Washington, D.C., is grounded in appeals to fairness, democracy, and representation. But selling the proposal with this line could spectacularly backfire for the Democrats, since Republicans in Democrat-run states such as California and Oregon feel the same way about the electoral dominance of urban cores like Los Angeles and Salem. The rural/red vs. urban/blue split spawned movements to create the State of Jefferson, while in Oregon, 11 counties are about to start the official process to join Idaho.

A successful campaign to create the Douglass Commonwealth will likely galvanize such state-level secessionists. They would argue that if the inhabitants of the District of Columbia are entitled to representation, so are they — especially in states like California, where recently Republicans have been shut out of state government. The immediate result would be greater GOP representation in Congress and the electoral college because there are a lot more Republican secessionist movements than Democrat ones, ranging from the West Coast to Michigan and Illinois, all the way to New York.

Obviously, the two situations are not identical. Changing state lines requires the approval of both state legislatures and Congress rather than the simple majority vote theoretically required to admit the Douglass Commonwealth.

It could mean a 52nd state

If Washington, D.C., were to become the 51st state, it could also mean the establishment of a 52nd. Considering the GOP's concern about losing political clout in the Senate, Democrats could concede the GOP an extra state, which would be carved out of a Democrat-controlled state such as California, Oregon, or Michigan.

In an op-ed published in the Wisconsin State Journal, filmmaker Michael Trinklein, whose primary claim to fame is documenting all the statehood projects that never made it into the Union, has proposed that Michigan could be the Douglass Commonwealth's road to statehood. Trinklein notes that states were historically admitted in pairs to preserve a balance of power in the Senate (or before 1861, free and slave states). For example, when Hawaii was admitted in 1959, Democrats got Alaska in return. Trinklein proposes carving out a new state called "Superior" from Michigan's heavily Republican Upper Peninsula as Douglass' companion state.

This would probably be the easiest way for the Douglass Commonwealth to gain GOP support for statehood in Congress. It would not, however, be the ace-in-the-hole, since the movement would still face the issues of the 23rd Amendment and Supreme Court challenges. Furthermore, the state losing territory, whether Michigan or some other place, would have to agree to the border changes –- another tall order that would become easier with support from the DNC apparatus behind it.

What does it mean for America?

So what does this mean for America? Georgetown professors Jessica Pozen-Bulman and Olatunde Johnson argue that the campaign is really about reconciling American society with changes to the Constitution since 1787. First, they argue that D.C. statehood is required under the 14th Amendment, which states that all those born on U.S. soil or naturalized are both U.S. citizens and citizens of their states. Subsequent changes have tied citizenship to the right to vote for representatives, whereas in 1800, most could not vote. If all citizens are entitled to state citizenship and the representation/voting it entails, then Washingtonians are being denied the 14th Amendment's equal protection by not having those rights.

But it is the authors' other argument that D.C. statehood is the future of American federalism that could redraw the American political landscape. Among the values of their definition of federalism is "minority rule." This is different from the classical definition, which focuses on protecting states from federal power. Under the new definition, D.C. statehood furthers the American promise by giving Washingtonians, a plurality of whom are Black, the right to govern themselves in what would be the only plurality-Black state. But it comes with one risk: If ethno-racial concerns are valid criteria for new states, other demographic groups, alongside with political and religious interests, will demand their own states on the same grounds. SCOTUS may have already set the precedent by upholding an Alabama ruling that allowed African-American voting districts in proportion to their population. The result could be many small separations into red and blue states — which would either be a blow to national unity or a safety valve to relieve political polarization.