The Shortest Tenured Speakers Of The House In US History

In a parliamentary system, the government is rooted within the legislature. The prime minister does not serve as the leader of the chamber, but they are the head of the majority or working coalition of parties that form the government (per the Federation of American Scientists). A vote of no confidence in the prime minister is effectively a vote against the sitting government, and a successful vote requires the formation of a new one, whether that be through new leadership or a snap election (per the BBC).

In the presidential system of the United States, the president and descendant executive functions of government are in a separate branch from the legislature. The speaker of the House of Representatives leads their party in that chamber, runs the floor, and sets the legislative agenda, but the speaker is not and cannot be a member of the administration while still serving in Congress. They may not even support the president's agenda. A speaker's removal, therefore, does not trigger the fall of a government.

That's not to say a speaker losing their gavel isn't consequential. Kevin McCarthy's short-lived and ignominious tenure in the job, undone by his own party in a first for the nation, is proof of that. But his roughly nine months weren't the shortest stint anyone's ever put in as speaker of the House. Per Axios, several speakers have had their careers cut short.

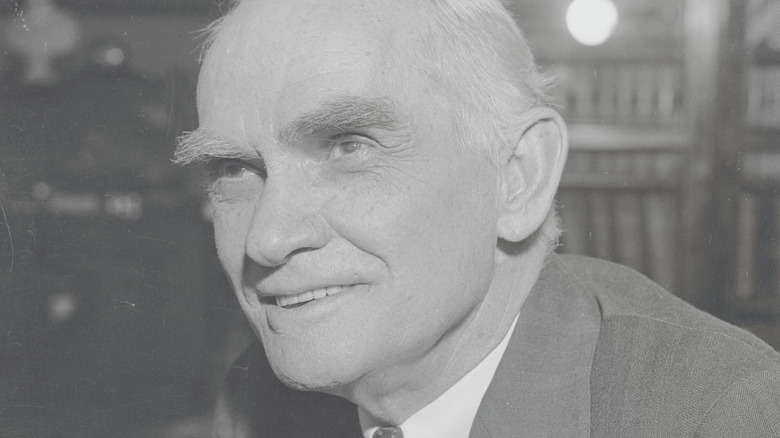

Joseph W. Byrns: 518 days

The U.S. House of Representatives History, Art, and Archives page chronicles the tenure of each speaker of the house. The shortest-serving speakers all did their time within one term (two years). Among them was Joseph W. Byrns, who was, according to the Knoxville Focus, known as the "non-vacation man." He had hardly any hobbies to speak of and poured all his time and energy into his work. Not that being a workaholic made him inaccessible. The Tennessee politician was also known for his genial manner and his openness to visitors, from fellow congressmen to his constituents, who needed to see him at any time. After first being elected to the House of Representatives in 1908 as a Democrat, Byrns rarely faced opposition in his reelection campaigns. He attributed the lack of competition to his dedication.

Byrns had become majority leader of the House by 1933, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt won the White House. According to the University of Tennessee Press, Byrns was a moderate in his party and sometimes hesitated over aspects of Roosevelt's New Deal program. But he loyally supported the president's agenda, and when the speaker's chair was vacated in 1934, he won the job and used its powers to gently move the New Deal forward. Still popular and hardworking, Byrns's speakership ended with his sudden death in 1936. President Roosevelt memorialized him as "fearless, incorruptible, unselfish, with a high sense of justice, wise in victory."

John N Garner: 458 days

Some speakers of the House of Representatives have lost the job due to disgrace, some to electoral defeat, and some to health. But there are more prestigious ways to leave behind the gavel — getting elected vice president of the United States, for instance. Such was the case for John N. Garner, whose speakership oversaw only the 72nd Congress, but whose time in the chamber stretched back to 1903 (per the House History, Art, and Archives).

Originally from Texas, Garner juggled interests in law and baseball as a young man according to the UVA Miller Center. Eventually settling on the former, he was a judge and state legislator before coming to Washington. He picked up the nickname "Cactus Jack," but far from being prickly, he carefully cultivated friendships among his colleagues and exercised influence on legislation (though he himself wrote very few bills). His friendships and party loyalty won him a spot on the Ways and Means Committee and, in 1931, helped win him the speaker's chair when the Democrats clinched a narrow majority.

Almost as soon as he won that leadership role, Garner gunned for another: the presidency. He didn't have the votes to win the Democratic nomination, but when he transferred his delegates to Franklin Roosevelt, Garner became the vice presidential candidate. A conservative Democrat (per Britannica), Garner grew increasingly uneasy with the New Deal and with Roosevelt's campaign for a third term. He mounted an unsuccessful primary challenge before retiring to Texas.

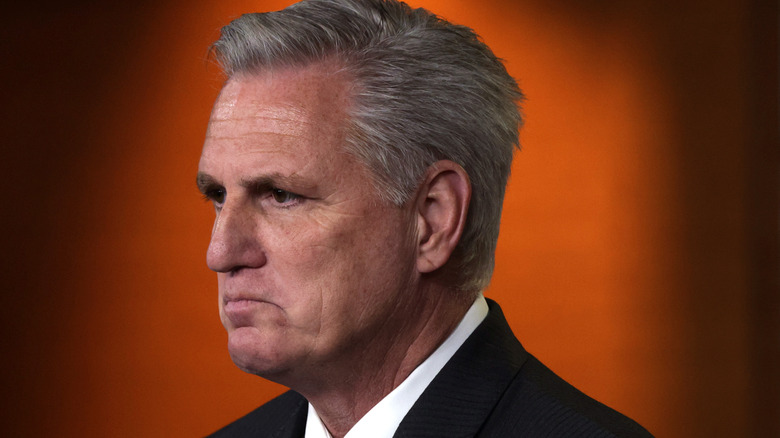

Kevin McCarthy: 270 days

Politico compared Kevin McCarthy to leaders of the Soviet Union, not in terms of political positions, but because he was the latest in a line of short-lived party leaders who sat atop their caucus uneasily. Republican leadership in the House of Representatives has grown more unstable since Newt Gingrich was speaker in the 1990s. But McCarthy's removal by vote, from a motion filed by a member of his own party, was unprecedented in American political history.

In a sense, McCarthy brought the vote on himself. As reported by PBS, he agreed to a change in House rules that would let any single member file a motion to vacate the speaker's chair, one of several conditions he granted far-right Republicans to win the gavel. Representative Matt Gaetz seized on that change in October 2023, citing broken promises capped off by McCarthy's reliance on Democrats to pass a bill averting a government shutdown.

Theoretically, McCarthy could have kept his job had been willing to offer concessions to the Democratic minority; most of the Republican caucus was in his favor, and it was a matter of just four votes whether he stayed or went (per The New York Times). But Democrats had their own issues with McCarthy's dishonesty. Members listed a reneged spending deal with President Joe Biden, a unilateral opening of an impeachment inquiry, and McCarthy's shifting attitudes towards investigating the January 6 insurrection as reasons not to save him (per The Huffington Post).

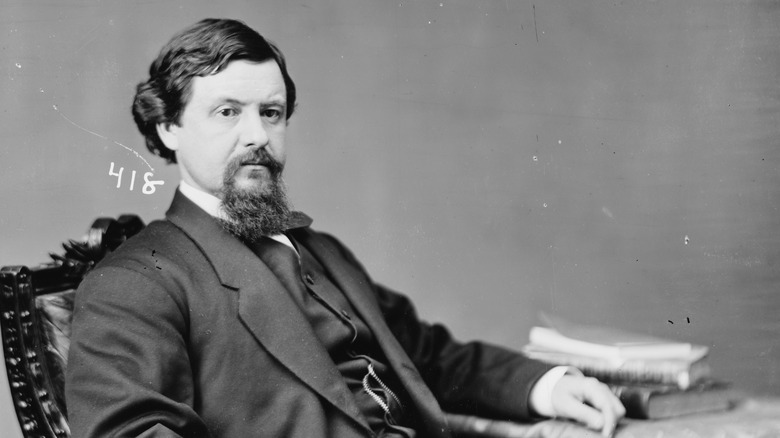

Michael C. Kerr: 258 days

Only two speakers of the House of Representatives have had shorter stints in the chair than Kevin McCarthy, for very different reasons. Michael C. Kerr's tenure was cut short, just as Joseph Byrns's was, by a sudden death (per the House History, Art and Archives). But had he lived, it's reasonable to assume that Kerr would have had a controversial, if not internally contentious, time in office.

Originally from Pennsylvania (per Politico), Kerr settled in Indiana as an adult. Before coming to Congress, he had been a state legislator and an elected reporter to the state supreme court. His bid for the latter job was initially foiled by Benjamin Harrison, the future president of the United States, but after Harrison joined the fight in the Civil War, Kerr took the position. He avoided combat and was only sent to Congress near the war's end. Elected to four consecutive terms, Kerr lost his reelection bid in 1872, only to regain his seat two years later. With his return to the 44th Congress came the speaker's chair.

Kerr's elevation to speakership was cause for alarm by Republicans, as well it might be. Kerr was a Democrat, and Democratic control of the House promised to further strengthen the growing reaction against civil rights after Reconstruction (per History). But the Atlanta Constitution, at least, admired him, writing after his death, "he commanded the attention of the house whenever he spoke."

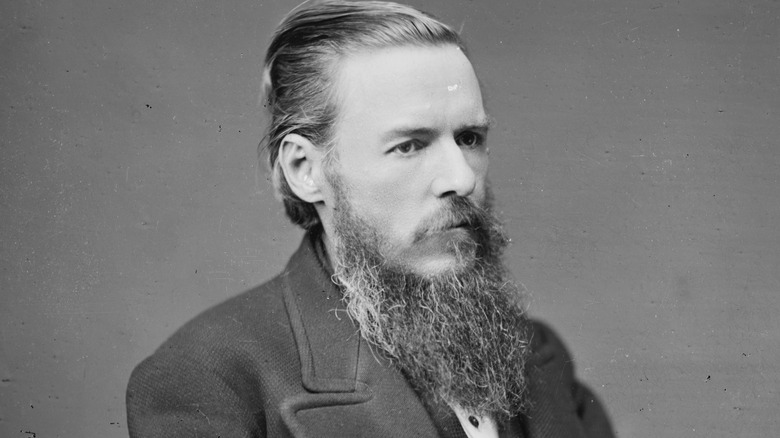

Theodore M. Pomeroy: 1 day

The shortest tenure of any speaker of the House of Representatives was a single day. Theodore M. Pomeroy had put many years into his congressional career. First elected in 1861 (per the House History, Art, and Archives), the New York congressman quickly made a name for himself. Per Politico, he was regarded as a skilled debater, an energetic statesman, and a friendly man who counted friends among politicians on both sides of the aisle. In his personal life, Pomeroy was friendly with Harriet Tubman, whom the American Pomeroy Historic Genealogical Association says helped care for the congressman's children.

During the Civil War, Pomeroy chaired two committees, Expenditures in the Post Office Department and Banking and Currency. After the war and the four years of Andrew Johnson's administration, Pomeroy announced plans to retire at the end of the 40th Congress. But on March 3, 1869, incumbent speaker Schuyler Colfax needed to resign. He would be sworn in as Ulysses S. Grant's vice president the next day. It was proposed by Massachusetts representative Henry Dawes that Pomeroy be elected in Colfax's place, at least for one day; the 40th Congress would end March 4. No one objected, and the well-liked Pomeroy took the speaker's gavel for the rest of his time in Congress. "The unanimity with which I have been chosen...is evidence of itself that your choice carries with it no political significance," he wryly observed, but he gave his sincere thanks all the same.