18 Scandals That Rocked America's First Ladies

Politics is about power. Power corrupts and leads people to do illegal things. Thus, it is no surprise that Washington, D.C., and the American political landscape are riddled with scandals, including occasions of grift, corruption, embezzlement, adultery, and other sex-related peccadillos, and influence peddling. In addition to real accusations, there are politically motivated ones, which even when false, get amplified in national media and tabloids, whether to sell papers or damage an opponent. Presidents, as the most visible figures of American politics, know this best, and there is no shortage of real and contrived presidential scandals. They could probably fill several volumes.

America's first ladies, however, have been mostly scandal-free — at least when compared to their husbands. But even they have run afoul of the press — or in the distant past, when mass media did not exist, of their social and political circles. Some scandals even dated to way before they moved into the White House or after they left. Usually, however, these minor incidents tended to fade away as people either forgot or the press moved on. Here are some first ladies' less proud or outright infamous moments.

Dolley Madison was accused of selling herself for votes

James Madison's wife Dolley is a national heroine for saving the Declaration of Independence and getting George Washington's portrait out of the White House as British forces were burning Washington, D.C. during the War of 1812, although contrary to the myth, she did not run out with it under her arm. But before achieving national fame, the first lady faced the D.C. rumor mill when her husband was serving as Thomas Jefferson's secretary of state.

The origins of the charges seem to lie in part with Dolley's alleged role as Jefferson's "surrogate first lady," which is a myth according to the White House Historical Association. This myth posited that Dolley acted as the main host of White House social events because Jefferson's wife Martha had died in 1782. Although Jefferson's own records do not support the idea, critics suggested that Dolley, who likely helped Jefferson host events when female guests were involved, was a bit too close to the widowed president, per UVA's Miller Center. Unsurprisingly, it did not take long for critics to accuse Dolley of being Jefferson's mistress. The anti-Dolley rhetoric ratcheted up in 1808, coincidentally right as James was making a bid for the presidency.

Although Jefferson thought the accusations absurd, it did not stop James' enemies from spreading further false rumors about Dolley's character. She was accused of helping her husband win the election of 1808 by getting intimate with various electors. Nothing stuck, and her husband won anyway to become America's fourth president.

Rachel Jackson faced bigamy allegations

Rachel Jackson was, technically, never the first lady. However, her truly public scandal was a huge part of her second husband's political life and presidential campaigns. Rachel married a man named Lewis Robards at 18. Unfortunately, the marriage failed. A jealous Robards accused his wife of multiple affairs, per historian Harriet Owsley, writing in the Tennessee Historical Quarterly. Among her alleged paramours was Andrew Jackson, whom Rachel met while he was staying with her mother as a boarder.

As the marriage deteriorated, Rachel left Robards and moved to Natchez in Spanish Mississippi, where Andrew frequently visited her. Because of this liaison, Robards accused his wife of eloping with another man in 1790, but he did not file for divorce until 1792, because he wanted part of his ex-father-in-law's estate. Andrew and Rachel, meanwhile, believed she and Robards were already officially divorced and had married in March 1791. But the divorce was not finalized until 1793, making Rachel an adulteress and bigamist on paper.

Writing in Ohio Valley History, historian Ann Toplovich noted that John Quincy Adams and his allies made the scandal, which had "enough ammunition to kill a regiment of presidential candidates," a central part of the 1828 presidential campaign. Adams' allies assailed Rachel, calling her unfit to be first lady and a danger to national morals. Although she had been legally found guilty of adultery, the strategy failed. Jackson won anyway, but Rachel died shortly after his victory, before his inauguration.

Julia Tyler starred in an ad

Julia Tyler, who married President John Tyler in 1844, was born in 1820 to New York State Senator David Gardiner and wealthy socialite Juliana Gardiner. Befitting of her station, she was held to strict a code of conduct, which limited her public exposure outside of acceptable social events, per the National First Ladies Library. Despite the restrictions, Julia showed her independent streak at 19 with a minor social scandal in 1839.

That year, Julia agreed to pose for an advertisement alongside a man for a dry-goods store called Bogert & Mecamly. She carried a handbag on which was written, "I'll purchase at Bogert and Mecamly's, No. 86 Ninth Avenue. Their Goods are Beautiful and Astonishingly Cheap." Julia was not named in the advert, but she was identifiable thanks to her nickname, "the Rose of Long Island," printed at the bottom. This was the first time a woman of her stature appeared in an ad – a big no-go for the time.

Her actions broke several rules of high society. A high-status single girl with many suitors was not supposed to lend her face and name to a commercial enterprise. Neither was she supposed to pose with a man who was not her husband. Her parents had impressed upon her the importance of finding a good marriage, and participating in the ad with an unrelated man was likely not a good look for suitors. In the end, the scandal faded when the Gardiner family left New York for Washington, D.C., and Europe, where she was presented before French King Louis Philippe I.

Mary Todd Lincoln was allegedly a spendthrift

Mary Todd Lincoln, wife of Civil War President Abraham Lincoln, was believed to suffer from mental disorders and a profligate spending habit. Prof. Michael Burlingame told the Chicago Tribune that the first lady "simply behaved terribly," even by modern standards.

The evidence comes primarily from the diaries of Sen. Orville Browning, who represented Illinois from 1861 to 1863. Among the entries is a conversation with one Judge David Davis, who called the first lady a "natural born thief." Davis accused her of stealing White House property and racking up $2,000 bills for clothes (~$70,000 today). An employee identified as "Stackpole" said she spent federal money on personal luxuries such as a silver plate, and embezzled money from the treasury with a White House gardener through manipulated invoices and a non-existent servant who was paid a $100-per-month (~$3,500) salary.

The rumors and scandals did not end with her White House tenure. According to author Deborah Jones Sherwood, Mary Todd tried to sell her White House wardrobe in 1868 under an assumed name — using her real identity as former first lady would have been scandalous. A pair of auctioneers, however, convinced her to reveal her true identity, along with letters backing it up. They would ostensibly convince buyers to get a piece of memorabilia. Instead, news of the auction ended up in the press, which excoriated her for conduct unbefitting of her station. It also failed, leaving her publicly humiliated and sticking her with an $800 (~$28,000) bill to get her wardrobe back.

Lucy Hayes' morals sent the White House into panic

Lucy Hayes, wife of President Rutherford Hayes, caused a minor scandal in Washington with her support of the Temperance Movement, which opposed excessive drinking and its accompanying social ills. Although a staunch opponent of alcohol, per the White House Historical Association, Lucy tolerated serving it during Russian Grand Duke Alexei's visit to America in 1877. But after that, Rutherford (not Lucy) banned alcohol from all White House functions, likely to court Temperance voters.

Lucy supported the ban, writing that it protected her own sons from the "first taste of what might prove their ruin" and provided a positive example for other mothers to follow. Although she did not institute the ban, Temperance organizations gave her all the credit anyway, with Temperance leader Frances Willard praising her as a woman whose example would make temperance "a fashion."

The praise was a double-edged sword. Opponents of the ban accused her of fighting a "temperance crusade," while White House staff complained that "she compelled [them] to astonish their stomachs with cold water for the first time in their lives." Sec. of State William Evarts, quoted in the book "Presidential Anecdotes" complained that at White House functions, "water flowed like champagne."

Some staffers, however, tried skirting the ban by spiking drinks and fruit to create what one reporter called "Life-Saving stations." One staffer even one-upped Lucy by having her serve cake, which, unbeknownst to her, he had spiked with rum. Her killjoy reputation cemented, she became derisively known as "Lemonade Lucy."

Frances Cleveland's marriage went from scandal to a hit

On June 2, 1886, 21-year-old Frances Folsom married President Grover Cleveland in the only-ever White House presidential wedding. But there was an air of scandal surrounding the match because the president, who was 49 at the time, had known the bride since her birth.

In 1889, The St. Paul Daily Globe – a pro-Democrat, pro-Cleveland Minnesota paper, ran a column that tried to paint the match positively. It argued that Cleveland's close relationship was Frances, the daughter of his friend, was innocent because he had always loved children. Eventually, the "bonds of affection" between the two "strengthened into the bonds of love." The paper cited an alleged exchange from one of the bride's friends between Cleveland and an 8-year-old Frances, in which she said she wanted to get married in the White House. Cleveland responded, apparently as a joke, that he thought she was going to wait to marry him.

In the end, contrary to expectations that he was marrying her mother, Cleveland married Frances. Yet, the extremely May-December marriage did not become a major scandal, likely because the press, including major publications like Harper's Weekly, celebrated the couple in their coverage, complete with congratulations, best wishes, and veiled references to promises of policy reform.

The positive coverage turned Frances into a superstar, fashion trendsetter, and advertising icon. Businessmen used her image to "endorse" their products – often without her permission. Further attempts to smear her as an adulteress failed, and she bore Cleveland three children.

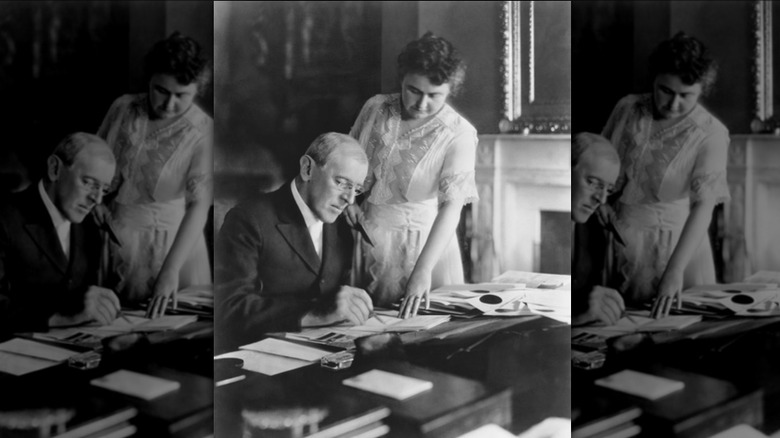

Edith Wilson ran the country

In 1919, Woodrow Wilson suffered a stroke during a tour promoting the Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I, to the American public, leaving him partially paralyzed and unable to fully execute his duties. He did not resign, and without the yet-to-be-ratified 25th Amendment, which would have allowed Vice President Thomas Marshall to act as president, there was only Article II Sec. 1.6 of the Constitution. That could have passed power to Marshall, but he would not accept unless Wilson stated in writing that he was inept and Congress declared the presidency vacant. Neither materialized.

Given this situation, First Lady Edith Wilson stepped in to fill her husband's role. In her memoir, the first lady wrote that she acted on the advice of Woodrow's doctors. They argued, she claimed, that the president's resignation would derail his vision of the League of Nations and kill the Treaty of Versailles – Wilson's only incentive to recover. Edith had her husband's full trust, so she followed the advice and became the presidential gatekeeper, deciding which matters and people merited the president's attention. In doing so, she effectively became the de facto president.

There was gossip that something was amiss in the White House. The public was aware of the stroke and the fact that Wilson was being shielded from guests. Interestingly, however, observers and Wilson's opponents concluded that the president had gone insane, something Edith vehemently denied. But the public never found out that his wife basically ran the White House after 1920.

Florence Harding was accused of killing her husband

Florence Kling Harding, dubbed "the Duchess" for her ambition and dedication to her husband's career, was the power behind the throne in the Warren Harding White House (1921-23). Unsurprisingly, she faced her share of scandals.

The future first lady hit the ground running young with two family scandals over her choices in men. The first resulted from her elopement around 1880 with one Henry DeWolf. Worsening the situation were rumors that the pair had never actually married, but lived in a common-law arrangement. She had a son named Marshall, whom her father Amos Kling adopted. She further scandalized her father by subsequently marrying Harding, then the publisher of the Marion Star.

Her biggest scandal by far, however, was a posthumous allegation from Justice Department official Gaston Means' 1930 memoir "The Strange Death of President Harding." He claimed through ghostwriter May Dixon that Florence had admitted to poisoning the president. She reportedly had tired of seeing her husband turned from a man with a "jovial confident demeanor" to a "hounded animal" as scandal after scandal piled up. So she "gave it [his medicine] to him."

Florence reportedly had "no regrets," about her actions. Historians, however, reject the narrative. Dixon later said, amid a financial dispute with Means, that much of the book's content was false. On the other hand, at least one allegation in the book – that Harding had an illegitimate child with mistress Nan Britton – has been proven to be true.

Grace Coolidge was accused of adultery with the Secret Service

College-educated Grace Coolidge, wife of President Calvin "Silent Cal" Coolidge, was known as an educational role model for women. In keeping with this image, she was scandal-free, with the exception of one incident that the press blew up to suggest she was an adulteress.

The story goes that in 1927, Grace and the president were on vacation in the Black Hills of South Dakota. One day in June, she decided to go hiking, taking her secret service escort, James Haley, with her. They were supposed to return by 1 p.m., when the president expected her back at the house for lunch. By 2 p.m., she still had not come back. She eventually did return at 2:15 p.m., apologizing to the president for her tardiness. Apparently, she had repeatedly stopped to pick wildflowers. In the end, Calvin was angry but forgave her. He did, however, remove Haley from her Secret Service detail. Later letters revealed she believed the dismissal was unfair.

The incident was ultimately a nothingburger. Because of Coolidge's anger and the removal of Haley from Grace's detail, however, the press suggested that she had gone on a long hike to have an illicit tryst with Haley. After all, he was a young bachelor, and the two were known to have a very friendly relationship. Although the accusations were unfounded, that did not stop papers like the Boston Herald (via "Presidential Wives" by Paul Boller) from running suggestive headlines like "Wife's Long Hike Vexes Coolidge."

Lou Hoover's Civil Rights scandal

President Herbert Hoover's wife Lou triggered a race-related row in the summer of 1929. She was due to host a White House tea for congressmen's wives, including Jessie DePriest, wife of the only Black congressman, Oscar DePriest.

The presence of Black visitors at the White House was nothing new, as historian Nancy Beck Young noted in her book "Lou Hoover: Activist First Lady." But Herbert Hoover was courting Southern voters, who feared Civil Rights leaders would use DePriest's visit to fundraise for their cause (which they did). Lou Hoover tried to compromise, respecting her husband's political aspirations while ensuring DePriest was properly received.

Lou's solution was to host several teas. The spouses of congressmen who might have taken issue with DePriest's presence were scheduled for earlier events to prevent boycotts that could embarrass the White House. DePriest was scheduled for the very last tea (not segregated), whose guests, mostly wives of cabinet members, were vetted for their racial attitudes beforehand. Several guests canceled other obligations to attend.

The event itself was a success — DePriest, per her own husband, was treated respectfully. But politically, the event drew anger, especially south of the Mason-Dixon line. Texas, Georgia, and Florida officially condemned her actions, while one woman wrote simply (via Prologue magazine): "Texas is so disappointed in you." Hoover, however, found praise in the Midwest for the "human decency of her act," while others noted the scandal was over nothing, given that "[t]here [was] nothing unusual" about African-Americans visiting the White House.

Eleanor Roosevelt faced rumors about her relationship with a female journalist

Eleanor Roosevelt's close relationship with journalist Lorena Hickok has drawn historians' interest because, at first glance, it seems borderline romantic. A 1979 New York Times exposé noted that the pair's 3,000 letters contained highly emotional language — almost sexual to modern eyes — including sentences such as "Hick darling ... Oh, I want to put my arms around you ... I ache to hold you close."

The phrasing has led some historians, such as Susan Quinn (via interview with Slate) to conclude the first lady and Hickok were sexually involved. Such a relationship would have been a major scandal in 1933, and it seems contemporary observers suspected as much. Eleanor appeared to suggest herself there was gossip, writing that she "care[d] so little what 'they [said].'"

In response, Eleanor's son, Franklin Roosevelt Jr., said there was nothing scandalous about the letters. Instead, he argued modern audiences "don't understand that kind of love, which occurred between people who needed each other and gave to each other." Rather than interpreting the letters as sexual, Franklin said his mother – a highly educated woman – had imbibed "that effusive form of writing" of English female authors such as Jane Austen and the Brontë sisters. She simply reproduced the style in letters to both sexes, although it appears over-the-top to modern audiences. Historian Rhoda Lerman echoed the sentiment, telling The Washington Post that Eleanor often preferred handsome young men for her affairs.

Bess Truman — last lady of the land

Today, membership in the Daughters of the American Revolution (the DAR) is open to any female descendant of Patriots who fought in the American Revolution, regardless of race, religion, or ethnicity. In October 1945, however, things were a bit different. Time reported that the DAR had barred the Black pianist Hazel Scott, the wife of Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, from the society's Constitution Hall because it was for "white artists only." In response, Powell demanded President Harry Truman discipline the society, but he responded that he could not interfere in a private organization's affairs. The Civil Rights Act, which outlawed race-based discrimination, had not been passed.

Bess Truman, who was an honorary member of the DAR, then inserted herself into the row. The Washington Post reported that she telegraphed Powell, saying she "deplore[d] any action which denie[d] artistic talent an opportunity to express itself because of prejudice against race or origin." But Bess did not resign from the organization, and even attended a DAR tea that was hosted that same afternoon in her honor.

In the end, the issue became a brief national scandal. After Powell called Bess the "last lady of the land," ordinary Americans decided to make their views heard. Among the most poignant was one who pointed out that Hazel Scott was being denied a performance even after she had raised money to fund World War II. Bess Truman, the writer argued, could have "give[n] up a cup of tea and a box of cookies to support the thesis for which [Black soldiers] died" – presumably the idea that all men are created equal.

Jackie Kennedy's alleged excommunication

Jackie Kennedy remained scandal-free as first lady, in contrast to her husband, President John F. Kennedy, who faced rumors of multiple extramarital affairs, including with Marilyn Monroe. She did, however, face a minor scandal over her second marriage to Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis. Archbishop of Boston and Cardinal Richard Cushing told the Southeast Missourian that Kennedy relatives and other interested parties wanted to stop the marriage, using Catholic doctrine to support their objections.

The California Desert Sun reported in October 1968 that the issue at hand was Onassis' divorce from his first wife, Athina Livanos. Since Jackie Kennedy was a Roman Catholic, she could not marry a divorced man without an annulment of his previous marriage – something which had to meet a specific set of conditions. Although Onassis' Greek Orthodox Church had given him a divorce, it was unclear if the Catholic Church recognized it as an annulment. Cushing defended Jackie. After all, they were friends. He had married her and JFK in 1953 and presided over the president's funeral mass a decade later.

Cushing called the rumors of her excommunication as a "public sinner" nonsensical. His statement, however, partially contradicted the Vatican, whose spokesman told Time that Jackie "knowingly violat[ed] the law of the church" by marrying a divorced man. She was thus ineligible to receive communion. Cushing acknowledged these issues, but maintained his defense. Jackie married Onassis anyway and received her last rites in 1994 before her death, suggesting she had either stayed in the church or reconciled.

Nancy Reagan faced rumors of being a hypocrite

Scandal knocked on Nancy Reagan's door in 1991 when author Kitty Kelley published "Nancy Reagan: The Unauthorized Biography." The book made some shocking allegations, accusing the former first lady of running the White House with Ronald Reagan as her puppet, smoking marijuana despite her "just say no" campaign, having an affair with Frank Sinatra, and living a promiscuous lifestyle in college and during her professional career. All of this ran counter to the wholesome family-oriented reputation the first lady had cultivated during Ronald Reagan's tenure.

The book was so controversial, that according to Kelley herself writing in The American Scholar, journalists at major outlets and publications excoriated their employers for giving it front-page coverage. Washington Post editor Karen Tumulty defended Nancy, telling Slate that "nobody deserved this." President Reagan accused Kelley of "exceed[ing] the bounds of decency," adding that "Nancy and [he were] truly upset and angry over the total dishonesty [in] her book." Kelley defended everything and never issued any corrections or retractions.

Although the allegations were biting initially, Nancy appeared to have gotten through it mostly unscathed. Most likely it was due to a combination of factors. Ronald Reagan was no longer in the White House, social media did not exist, and there were no political points to score with decades-old rumors. Alternatively, Newsday columnist Harrison Salisbury suggested that the charges were nothing new – the media had just ignored them to maintain access to the Reagan White House. Nancy never seems to have personally responded to the book outside of her husband's statements.

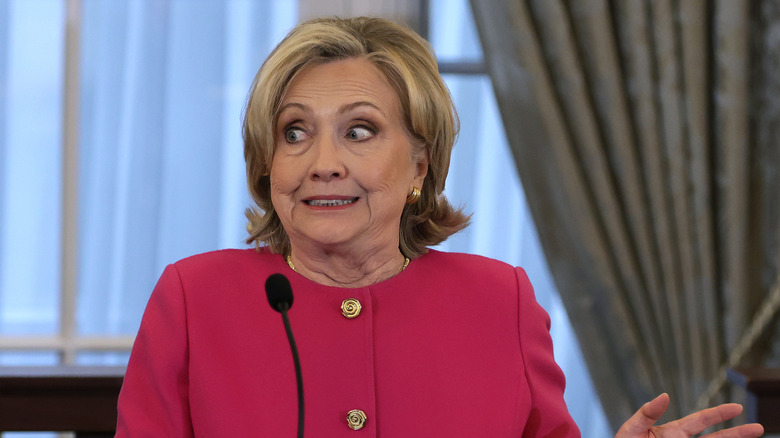

Hillary Clinton got Bill's administration sued

Hillary Clinton has been embroiled in numerous scandals, either in tandem with her husband, President Bill Clinton, or during her tenure as Barack Obama's secretary of state. These range from accusations of financial misconduct in the Whitewater and Cattlegate scandals to allegedly mishandling the 2012 Benghazi embassy attack. As first lady, her presence got the White House sued over her role in an attempted 1993 healthcare overhaul the GOP dubbed "Hillarycare."

In 1993, The New York Times reported that Bill had nominated his wife to head a panel on overhauling the American healthcare system. This was the first time a first lady had been "assigned such an influential, policy-shaping position." But she did not draw a salary, making her status unclear and creating transparency issues. This led to a lawsuit from several healthcare lobbies for panel records. They argued that the Federal Advisory Committee Act of 1972 (FACA) required any committee or task force containing members from outside the federal government to meet publicly. Hillary, they argued, was not a government official, subjecting the panel to FACA disclosure requirements.

The administration won in appellate court when Judge Laurence Silberman ruled that Hillary's presence on the task force did not automatically require public disclosure, and remanded the case to a lower court. This overturned a previous ruling, which had ordered the task force to turn over its records on the grounds that Hillary was not a salaried public officer. In the end, it did not matter, as the Senate shot down the resulting healthcare legislation the panel formulated.

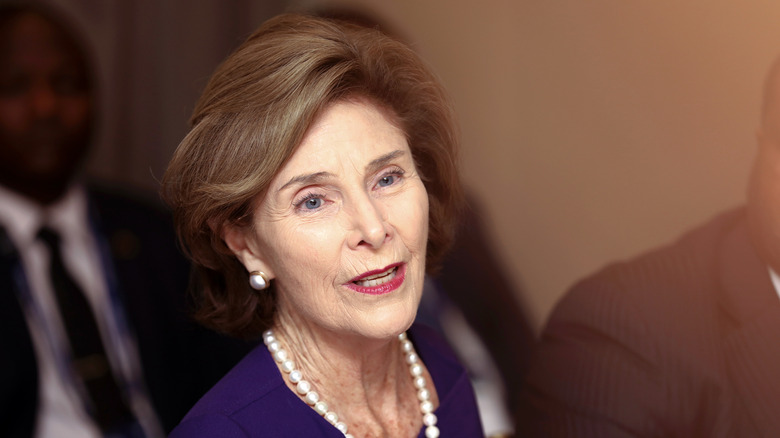

Laura Bush's teenage car crash risked becoming something bigger

Laura Bush remained scandal-free, despite the turmoil of her husband George Bush's presidency, which included 9/11, the Global War on Terror, and the invasion of Iraq. In 2000, however, a car accident from her teenage years surfaced that risked becoming an accusation of homicide.

According to a 1963 report from the Midland, Texas, Police Department and an Associated Press report on the incident from 2000, the 17-year-old Laura Welch was driving after dark with her friend, Judy Dykes, on Highway 349. When they came to an intersection, she missed a stop sign and hit another car in the middle of the intersection, sending both spinning off the road. The driver of the vehicle that was hit, 17-year-old Michael Douglas, was killed, while Dykes and Laura were taken to the hospital for minor injuries. It is unclear if she was speeding, but she did not face charges.

In response, Laura Bush issued a statement through spokesman Andrew Malcolm, saying, "To this day, Mrs. Bush remains unable to talk about it." Her only other statement was that the event was "crushing" for herself and Douglas' family. The press, perhaps out of respect, did not make it a campaign issue. She broke her silence in her 2010 memoir "Spoken from the Heart," explaining that her inattentiveness, the darkness, and the size of her car all contributed to the accident, which wracked her conscience for years after.

Melania Trump Was accused of running a fake charity

Melania Trump has mostly eschewed the spotlight since leaving the White House in 2020. But in February 2022, she resurfaced to respond to allegations of running a fake charity. The New York Times reported the former first lady was raising money for a charity called Fostering the Future, which was supposed to help foster children access higher education and job training. However, no such organization was registered in either New York or Florida and thus, did not appear to exist.

The details are a bit unclear, but the NYT reported that at least one scholarship with an identifiable recipient had been given out through the initiative. Florida law requires charities or any organization raising charitable funds to register with the state, which resulted in a state investigation into the paper's allegations.

Melania responded to the allegations on Facebook, accusing the media, which she called "typically corrupt," of twisting her initiative. She said that she was simply working with a donor-advised fund called Bradley Impact to decide where to funnel charitable donations in support of foster care. She assured all procedures were being properly followed. In a separate statement to Business Insider, her spokesman clarified that "Mrs. Trump does not operate a 501(c)(3) charitable organization. 'Fostering the Future' is the platform's name and part of a Be Best initiative." So far, there have been no major developments, and the allegations have died down amid her husband's slew of federal and state criminal charges.

Jill Biden allegedly cheated on her ex with Joe

The official Biden love story, as Jill Biden told CNN's Piers Morgan, is that Joe Biden met Jill at a fundraiser, saw her picture, and decided he wanted to date her. So Frank Biden, Joe's brother, gave Joe her number. Joe then called her and asked her out on a date to a movie in Philadelphia. But the first lady's story was cast into doubt when Jill Biden's ex-husband Bill Stevenson claimed the truth was less wholesome.

In September 2023, Stevenson appeared on Newsmax's "Gregg Kelly Reports". Stevenson said he was friends with Joe and that he supported and even bankrolled his Senate run. He claimed Joe repaid his support by having an affair with Jill, calling her story about the Philadelphia movie date a lie. Instead, he alleged, Joe and Jill went to a Chinese restaurant in March 1974 while she was still married to Stevenson. One of his friends even allegedly saw and photographed them together.

In a response to a separate interview Stevenson gave to Inside Edition, Jill said her ex's "claims [were] fictitious, seemingly to sell and promote a book." In her version of the timeline, she and her husband separated in the fall of 1974. The relationship with Joe Biden did not start until 1975.