The True Story Of The 'Wise Gals' Of The CIA

Intelligence and espionage have a long history, though that may not necessarily be a big surprise. After all, it's not hard to guess why covertly gathering information would be quite the asset to anyone of note.

In the U.S. alone, well, espionage is as old as the country itself, quite literally. Older, really, if you wanted to be technical about it — the Culper Spy Ring operated during the American Revolution, after all. Espionage continued to live on in American operations as the years passed, and women have been a part of that tradition. While the mysterious "Agent 355" — a female spy at one point thought to have been a part of the Culper Spy Ring — likely didn't exist, there were plenty of others to follow. Harriet Tubman, for example, who was most known as a conductor on the Underground Railroad, actually served as a Union spy by the time of the Civil War.

But if you want to get into the more modern view of American espionage, then you'd have to turn your view to the mid-20th century. With the advent of World War II, plenty of countries were making use of spies, with the U.S. government creating the Office of Strategic Services — also known as the OSS, and the direct predecessor of the CIA. Women played a huge role in OSS operations (and in covert operations for other countries), but the end of the war was far from the end of frustration for them.

Sexism in the world of espionage

Despite the fairly numerous examples of women proving their worth as spies — and even running large-scale covert operations — that didn't mean that there wasn't an uphill battle for them to fight against public perception and societal standards. In other words, sexism was (and would continue to be) a very prevalent problem.

Honestly, direct quotes speak for themselves. An examination of workplace conditions compiled by female CIA agents in the 1950s compiled quotes from male officials which are, unfortunately, unsurprising for the time. Included were claims that "women are more emotional and less objective in their approach to problems than men ... [and] can't work under the pressures of urgency" (via CIA). Over in Europe, similar officials made many of the same claims: "An agent should be calm, unostentatious and reticent. Women are emotional, vain, loquacious. They fall in love easily and without discrimination. They are impatient with the strict requirements of security measures. They withstand hardships poorly" (via History). Women currently working with the CIA — such as analyst Gina Bennett — have also made reference to those problems and how entrenched they are at the agency, saying, "People treat it as only men have a calling to serve their country and it's unnatural for women to do it" (via Newsweek).

Funnily enough though, the CIA's predecessor (the OSS) was something of an exception to the rule, with thousands of women brought on as officers, specifically because they were seen as particularly capable.

Women had unique advantages in espionage

The state of espionage and the opinions on the abilities of women at spies were certainly a mixed bag in the mid-20th century. Of course there was the sexism that you'd almost expect, but there was also no denying that there was certainly a reason there were quite a few successful female spies. Obviously they were just as capable and courageous as their male counterparts, but they actually possessed some unique advantages, as well.

See, while period-typical misogyny was a social problem, it actually provided something of a shield to female spies. Most people didn't think that women could be spies, and as a result, female spies were naturally far less suspicious. They could come and go as they pleased without drawing questioning eyes or inviting searches of their belongings — a pretty clear boon, whether they were delivering secret messages, or traveling to covert meetings. Some women even took to weaponizing the way in which society perceived them as weak, playing into those expectations to make their way out of dangerous situations.

[Featured image by Reino Kalevi Lehtonen via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0 DEED]

The founding of the OSS

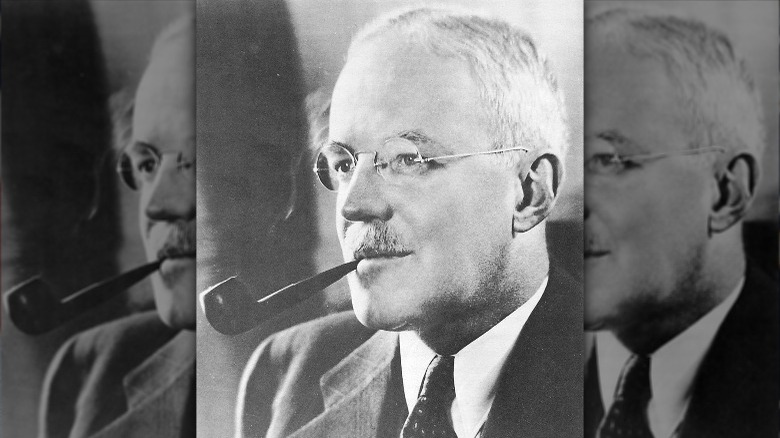

Prior to World War II, the U.S. didn't actually have a dedicated, centralized agency for the collecting of intelligence and implementation of covert operations. The bombing of Pearl Harbor changed that, though, and by mid-1942, the Office of Strategic Services (the OSS) was up and running with William J. Donovan (pictured above) at its head. The agency really laid the groundwork for modern-day intelligence techniques — in particular, analyzing all forms of communication, maps, and reports, rather than physically sending spies into enemy territory to gather information (though paramilitary operations weren't out of the question, either).

Donovan was also a big part of why the OSS brought so many women into its ranks. He was apparently unique in that he didn't ascribe to the tired idea of intelligence being a club meant only for certain kinds of men. Rather, he saw value in diversity, placing much more value on ability and, perhaps above all, passion; there were military officers in the ranks of the OSS, but there were also artists, academics, and thousands of women. In fact, one of his most trusted associates was Eloise Page, a young Virginian socialite who technically worked as his secretary. In reality, she found that her boss wanted to discuss strategy and intelligence with her, getting her opinions on everything that was happening. She ended up playing a major role in the strategy behind the invasion of North Africa, and as the war continued to rage, her connections with British intelligence helped develop counterintelligence networks between the two nations.

Women at the OSS

The women who worked at the OSS during World War II certainly had some impressive and, in some cases, harrowing stories to tell. Truly, the stories of these women of the OSS — and, later, the CIA, in many cases — are incredible.

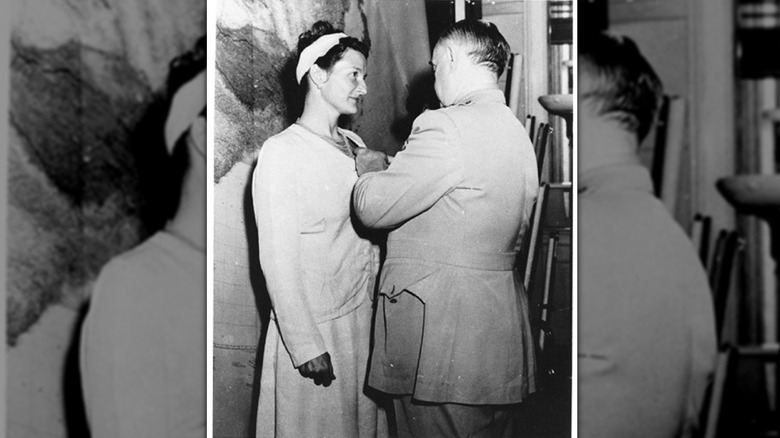

Perhaps the most well-known of these female spies is Virginia Hall (pictured above), who was quite possibly America's most important spy of the war — if nothing else, the Gestapo actually tried to inspire fear by calling her "The Enemy's Most Dangerous Spy" (via NPR). Despite walking with a wooden leg, Hall was actually working as a spy in France before the OSS was founded. She was a literal master of disguise, managing to keep the Gestapo off her scent with multiple different identities, all while running her own intelligence network, which would grow to about 1,500 people. And even when the Gestapo almost caught her, she escaped by hiking for 50 miles through the snowy Pyrenees Mountains. With a prosthetic leg.

But there were many other women at the OSS, aside from Hall. Barbara Lauwers was an expert in propaganda, making double agents out of prisoners of war and spinning together The League of Lonely War Women — a campaign to demoralize German soldiers. Cordelia Dodson became a part of the X-2 counterintelligence network while also tracing Nazi money and escorting prisoners of war. And there are plenty more besides, many of whom continued their careers in intelligence, after the dissolution of the OSS in 1945 and the creation of the CIA in 1947.

Eloise Page: The Iron Butterfly

While you can generalize the impact that these "wise gals" of the CIA had on the agency (and, frankly, on the balance of international power), it's much more interesting to actually see exactly what some of them accomplished. And Eloise Page, the trusted associate of the OSS founder William Donovan, is a pretty good place to start.

Later known as "The Iron Butterfly," Page was one of the first people employed at the CIA and rose through its ranks quickly. She became one of the highest-ranking officers of the Directorate of Operations, as well as the Chief of Scientific and Technical Operations, the Deputy Director of the Intelligence Community staff, and the Chairman of the Critical Collection Problems Committee. Those many positions are impressive in and of themselves, but none of them are the thing that she's most known for. Rather, she was looking toward not only earning the highest-ranked position for an operations officer — a CIA Station Chief — but also ensuring that she was given a respectable and challenging assignment. She even turned a few before securing her desired position in Greece, becoming the first-ever female Chief of Station in the 1970s. From there, she influenced operations that took place all around the world and became one of the leading experts on terrorism.

Inequality at the CIA

One of the most prevalent common threads between the stories of all of these women is the fairly apparent discrimination that all of them faced as a result of their gender. Even before compiling official reports to concisely file those complaints to the higher-ups, many female CIA agents knew what the problems were: differences in pay, different standards for recognition and promotion, different expectations, and limitations imposed on them for superficial reasons. It was just unfortunate that the reasons behind those conditions were deep-seated, simply born of sexism, not even attempts at logic. An actual quote from a male CIA agent reads, "Men dislike working under the supervision of women and are reluctant to accept them on an equal basis as professional associates" (via CIA).

So, really, it was easy to see why women were upset, and in 1953, they brought their grievances directly to the CIA's new director, Allen Dulles (pictured). With Dulles having already promised to improve morale, they questioned whether he would take the time to look into workplace discrimination and recognize the hardships they faced. Dulles responded, saying, "If there is discrimination, we're going to see that it's stopped" (via CIA), and he ultimately did follow through, leading to one of the first-ever studies on gender discrimination in the workplace.

The Committee on Professional Women

With Director Allen Dulles willing to investigate the discrimination faced by female CIA agents, he asked that the CIA's Inspector General look into a solution. And that solution? The Committee on Professional Women.

The committee was composed of a total of 22 women (13 regular panel members and nine alternates), all of whom had already had long careers with the CIA, having been with the agency since its inception. They had all been pulled from a variety of different departments and fields to offer the widest possible perspectives and had their first meeting in the summer of 1953. They were officially tasked with determining whether discrimination existed, and then subsequently tasked themselves with recommending ways that the agency could better itself and help promote women's careers.

That said, though, the women and their mission still weren't looked upon fondly by their male colleagues, who typically viewed them with disdain. The committee was even nicknamed "The Petticoat Panel" — a name which the women themselves weren't exactly fond of, but accepted nonetheless, if only because its existence was rather indicative of the situation they faced. And as for their designation as "wise gals"? That also came from a quote from a male officer: "I think it is important to remember how it came into being ... because [of] a couple of wise gals" (via Nathalia Holt's "Wise Gals").

The Petticoat Panel was a new experience

The mere inception of The Petticoat Panel was a groundbreaking thing on its own. Of course, there's the fact that the CIA had never before conducted a study on workplace discrimination; for that matter, the topic hadn't been raised all that much in workplaces in general. So in a large-scale, societal sense, this was quite a momentous leap forward.

But there's a personal aspect to this, as well. Many of the women on the committee had never actually gotten a chance to know each other in the past. That was for a number of reasons, granted; the nature of covert work that took them all over the globe would typically have that effect. Not only that but they were all accustomed to being constantly surrounded by men in their line of work. But in this setting? They could finally open up and speak freely with each other, sharing both their grievances and their stories. And it wasn't only the 22 women officially on the panel. Rather, the women they interviewed were also given the space to vent their own frustrations in a way that social norms typically didn't allow for.

The findings of the Petticoat Panel

In November 1953, the committee submitted its final report, compiling plenty of data on pay ranges and overall employment numbers regarding women at the CIA, as well as anecdotal evidence of discrimination (albeit with a fair bit of emphasis on the former).

While the report did include some interesting statistics in the CIA's favor — namely, that compared to other federal agencies and national employment, the CIA was employing more women and paying its staff better on the whole — it also pointed out the many times when women just weren't treated the same as men. When it came to higher-level positions, men held a clear majority of those spots. This wasn't to say that there were no women in influential positions, but even when women were doing the exact same work, they were, on the whole, being paid far less than their male counterparts.

Not only that, but executives had claimed that the persistent issue of women leaving the CIA was due to marriage or pregnancy — a notion that the panel found to be false. This wasn't a matter of personal lives; rather, women were leaving because they felt they were being underutilized and underpaid. On that note, the report even made mention of a similar anecdote: a quote that claimed women were unsuited for intelligence work because they might leave for family. A notion that the panel, once again, debunked. After all, there was no reason to think a male agent wouldn't leave unexpectedly for personal reasons. What was really the difference?

Their findings fell on deaf ears

To be entirely fair, while the "wise gals" were determined to make a difference and better the CIA for the generations of women to follow in their footsteps, the committee's chairman, Dorothy Knoelk, also made something quite clear from the outset. In her own words, "The status of women in the Agency would not be overemphasized as a major problem in the CIA" (via CIA).

But even so, the report was met with a decidedly chilly response. Officials responding to the report only really offered praise for the quality of work that the panel had done, but when it came to tangible change? They didn't think that any was necessary, believing that there was still some need to discriminate by gender and that existing regulations worked just fine.

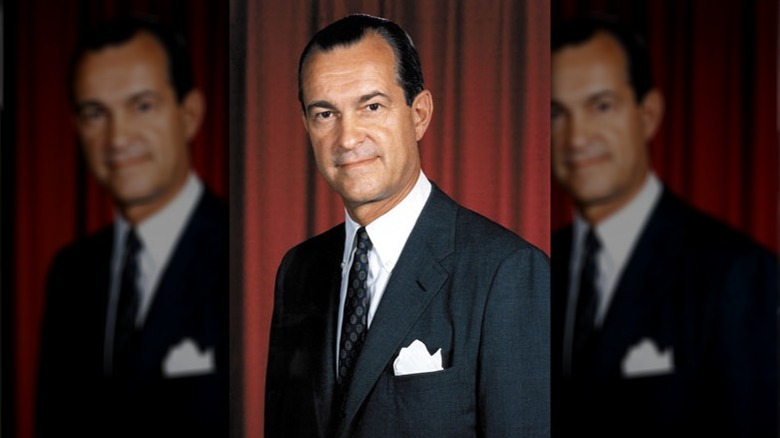

That was just the official response, though; the actual discussion was considerably colder. While some did recognize that these were genuine problems, many others (including future director Richard Helms, pictured above) parroted much of the same sexism present in the report, such as the belief that women were inherently more likely to quit their careers at unexpected times. And then there were those who were much more openly hostile, complaining about how inconvenient ambitious women could be, that college degrees had made them think themselves obnoxiously capable. Or, to sum up the misogyny: "It is just nonsense for these gals to come in here and think the Government is going to fall apart because their brains aren't going to be used to the maximum."

The legacy of the wise gals

When it comes to short-term changes as a result of the "wise gals" and the Petticoat Panel, it's unfortunately difficult to find anything good to say. The CIA did, in fact, seem to largely ignore the recommendations made by the committee. At best, one of the panel members said that women were subsequently allowed limited access to the CIA's gym, and in the year, more women were nominated for entry into the CIA's training program (though it doesn't seem like more were admitted, compared to previous years). It's really not all that much.

But as the years passed, the work that the "wise gals" had done started to bear some fruit. In the 1970s, workplace discrimination was once again a prominent issue, this time with regard to both gender and race, and during that time, some of the recommendations made by the 1953 report had actually come to fruition. Not only that but there was an even more concrete connection between the decades: The CIA's first Federal Women's Program Coordinator was Margaret McKenney, who had also been one of the members of the Petticoat Panel.

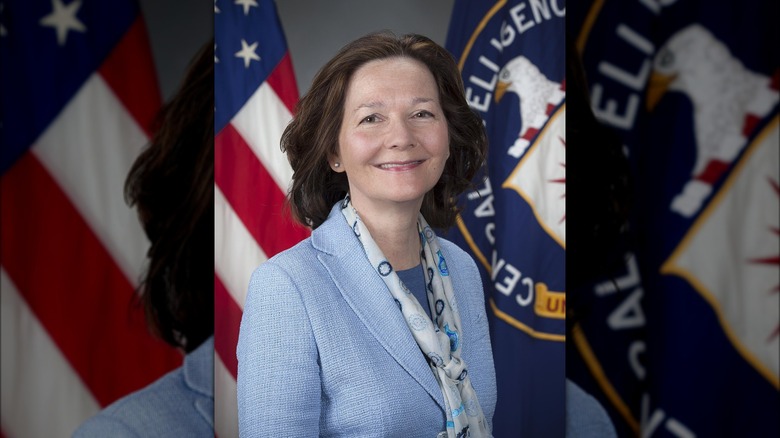

In the decades to follow, the CIA continued to examine its treatment of women, with female agents spearheading some of the most prominent cases in the CIA's history (the Aldrich Ames case, for example, was solved by Jeanne Vertefeuille) and rising to more positions of power, as Gina Haspel (pictured above) did in 2018, becoming the first female CIA director.