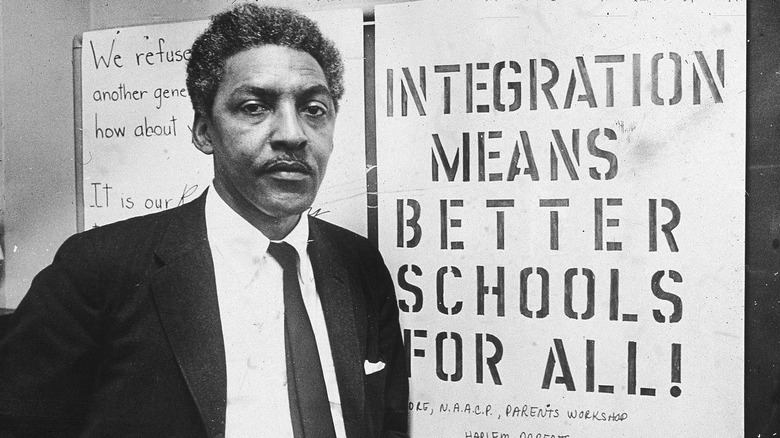

Bayard Rustin's Relationship With MLK Explained

One-time right-hand man to Martin Luther King Jr., Bayard Rustin had a close relationship with the civil rights giant, and it was filled with highs and lows. Notably, he pushed King toward pacifism, shaping the preacher's ideas and methods to a large degree. Rustin is less well-known than the fiery public speaker but no less important — it was he who organized the 1963 Civil Rights March on Washington at which King delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech. His considerable organizational skills would help King a great deal, albeit Rustin proved to be slightly too radical for his contemporaries at times.

Rustin was in the spotlight far less often than King because he was vulnerable to attack. The activist was gay in an era before the gay rights movement had taken off, and he was even arrested in 1953 on "sex perversion charges" for having sex with men. He also had a long history of supporting causes that were unpalatable to many Americans at that time. He joined the Young Communist League in the 1930s (although he would later leave) and was arrested as a conscientious objector during World War II. Ultimately, Rustin proved to be an easy target for critics of the civil rights movement, although he would continue to work with King many times before King died.

He called for pacifism

Bayard Rustin was raised a Quaker and was a committed pacifist. He first met King in 1956 in Montgomery, where the famous bus boycott was taking place, and the pair became good friends right away. Rustin was older than Martin Luther King and had a more thought-out philosophy on protest. While King had taken an interest in Gandhi, he was not yet fully committed to a creed of non-violence and actually kept guns in his house at the time. Rustin on the other hand had actually been to India in 1948 to study Gandhi's philosophy, and he passed his ideas on to the famous preacher.

Rustin told King that his best bet to drum up support was to simply let himself and his followers get arrested. So long as they committed no acts of violence in response, others would see that they were in the right and rally around them. To cap it off, he wrote a speech for King to use at the boycott that focused on non-violence. The boycott of course was a huge success, and segregated buses were ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court later that year, cementing King's status as a civil rights celebrity.

Bayard Rustin is sidelined

Unfortunately, Bayard Rustin was soon seen as a liability due to his sexual orientation. Fears about Rustin became so intense that Martin Luther King buckled to pressure and created a committee to decide whether or not they should keep working together.

In 1960, when King organized a march on the Democratic convention, Congressman Adam Clayton Powell tried to stop the event by blackmailing Rustin and King. He told King that if they did not call a halt to the march, he would spread a rumor that the pair were lovers. Although Powell's nefarious scheme was foiled (King threatened to blackmail the congressman in return with pictures of women he'd slept with), the unfortunate event did do some damage to Rustin. Although Rustin had helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1956, he was forced to leave the organization in 1960 as a result of the debacle.

It was in no way the last of Rustin as an activist, however, and he became heavily involved in the momentous 1963 March on Washington. On this occasion, he was once again punished for stepping back into the spotlight when Congressman Strom Thurmond raged on the senate floor that he was a "Communist, draft-dodger and homosexual" (via The Guardian).

King and Rustin diverge

By the mid-1960s, Bayard Rustin and Martin Luther King's philosophical differences created a wedge between them. According to Jerald Podair's biography "Bayard Rustin: American Dreamer," despite his pacifism, Rustin was far less concerned about the war in Vietnam than King was. Instead, Rustin wished to focus solely on eradicating poverty and warned King not to speak against the war, an order King ignored. Rustin also believed that King was in danger of alienating the Democrats with his protests, some of which challenged the party too directly — something Rustin felt they could not afford to do.

Ultimately the idealist King and the more pragmatic Rustin grew apart in the years leading up to King's death. They did however still interact — it was Rustin among others who urged King to go to Memphis, where he was shot and killed, in order to support striking African-American sanitation workers. In the immediate aftermath of his death, Rustin continued some of King's work, taking up King's Poor People's Campaign.