Every Amendment After The Bill Of Rights Explained

The U.S. Constitution was drafted in 1787, ratified in 1789, and has been the Supreme Law of the Land ever since. But it has not remained static – the Founders gave their successors the ability to amend and change it in response to evolving societal and political circumstances. Nor was it a perfect document. There were numerous ambiguities regarding the rights of the federal government vs. the states and the people that had to be resolved through the amendment process. In the case of the federal-state conflict over slavery, not even the Civil War proved to be a definitive solution. An amendment was needed to end that, too.

In total, 17 additional amendments have been added to the Constitution after the Bill of Rights (the first 10). Some, like the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote, are well known due to the immense impact they had on American political, economic, and social life. Others, like the 12th and 22nd amendments, are less known, but no less important, since they created the modern process for presidential contests. Here is every amendment after the Bill of Rights explained and the oft-convoluted circumstances that led to the creation of each.

11th Amendment

The 11th Amendment began with a 1793 Supreme Court case. Robert Farquhar had sold the state (then colony) of Georgia war materiel during the American Revolution, but never received payment. The executor of Farquhar's estate, Alexander Chisholm, sued Georgia for payment in 1792. Because the lawsuit involved a private individual from another state (here, South Carolina), there were questions over jurisdiction, so it went to the Supreme Court in Chisholm v. Georgia.

As noted in the opinion, Georgia did not appear before the court, which threatened to default the case to the plaintiff. The state reasoned that as a sovereign entity, it was immune to lawsuits in federal court originating from other states or their citizens, unless it explicitly waived its sovereign immunity and consented to the lawsuit.

The case was an early harbinger of the states' rights debate – a question of whether states were federal subjects or independent entities alongside the federal government. The court concluded it was the former. It cited Article III, Sec. 2.1 of the Constitution in Chisholm's favor, which states that the judiciary's authority would extend "to Controversies ... between a State and Citizens of another State." Only Justice James Iredell (above) dissented in Georgia's favor.

In response, Congress validated Iredell with the 11th Amendment, which overturned the decision and forbade the federal judiciary from involving itself in lawsuits against states by citizens of other states. The amendment does have exceptions, however. Congress may abrogate a state's immunity, while citizens may also sue officials acting unconstitutionally on behalf of a state in federal court through the ex parte Young doctrine.

12th Amendment

Imagine it's Election Day, 2024, and the electors vote for their two top presidential picks instead of a ticket. Two political rivals such as Donald Trump and Joe Biden get the first two spots and end up serving as president and vice-president. This is how the system worked before the 12th Amendment. Before 1804, electors only voted for the president, choosing two candidates from a pool of several. The winner became president and the runner-up, vice president.

The election of 1800 exposed the system's problems when Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr ran "together" against John Adams. There were no presidential tickets then, but Jefferson and Burr were from the same Democratic-Republican Party. They intended to serve as president and vice-president respectively. But since the system did not electorally differentiate between the two positions, they ended up tied repeatedly. Jefferson won on the 36th ballot, but this sort of limbo was better avoided in future, especially in times of crisis.

In response, Congress proposed and states ratified the 12th Amendment, which created the modern electoral college rules. It requires electors to cast one vote for the office of president, and one for the office of vice-president, while making the sitting vice-president responsible for certification. The winners needed a simple majority (today 270) to win. If there was no majority, the presidential election would default to the House, with each state having one vote, while the vice-presidential election would go to the Senate. The amendment also set the stage for the presidential ticket, although those did not really take off until 1831 when party conventions began nominating candidates instead of Congress.

13th Amendment

The 13th Amendment to the Constitution came in 1865 on the heels of abolitionism and the American Civil War. In 1863, Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which contrary to popular belief, only freed slaves in some militarily-occupied areas of the Confederacy. Areas such as the "border states" – slave states that had remained loyal to Washington – and the City of New Orleans were exempt.

When the surrender at Appomattox officially ended the Civil War on April 9, 1865, slavery was still legal and the question of whether Congress could ban it was not settled. But that question had caused the antebellum firestorm over slavery in the first place. Lincoln himself believed that Congress could not end it, hence his 1860 promise to respect slavery in the South. The Confederate Constitution showed a similar concern in Article I, Sec. 9.4, which forbade the Confederate Congress from forbidding slavery.

To resolve the issue, The Republican party proposed the 13th Amendment, which despite roadblocks in the House, passed in December 1865. It abolished "slavery [and] involuntary servitude" in all U.S. jurisdictions. But it contained one exception: prisoners could still be sentenced to involuntary labor as restitution for crimes committed – a problem that prison reform groups have argued constitutes slavery by another name.

While the amendment abolished all "involuntary servitude," U.S. law makes it clear that it applies to human bondage – as in one human owning another. A U.S. citizen, for instance, cannot invoke the 13th Amendment to avoid a military draft or jury duty – no matter how much he might view these as "involuntary servitude."

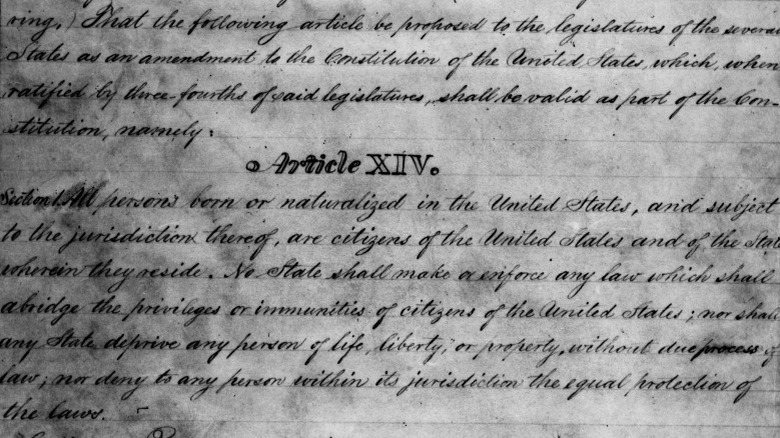

14th Amendment

The 14th Amendment, passed in 1868, deals with the aftermath of the Civil War, Reconstruction, and former slaves. Sections 2-4 covered the rights (or lack thereof) of former Confederates and issues around the public debt. The meat, however, is in Sec. 1, which says that all people born on U.S. soil and subject to American jurisdiction are citizens, and cannot be deprived of their rights as such – a lightning rod today when immigration is a key issue.

The 14th Amendment's principal intention was to reverse the Supreme Court's 1858 Dred Scott v. Sanford decision, which denied citizenship to U.S.-born African Americans. But Sen. John Conness of California also said the amendment would apply to the U.S.-born children of immigrants. His colleague, Michigan Sen. Jacob Howard, however, said the amendment would not apply to "persons ... who are foreigners [or] aliens ..." There seemed to be two competing definitions of jurisdiction: one meaning subject to U.S. law at birth, and another that had an element of sole parental allegiance to the United States.

The Supreme Court partly settled the question in the 1898 case Kim Ark Wong v. U.S. SCOTUS ruled that Wong was a U.S. citizen because he was born in San Francisco to Chinese citizens legally residing in America and not employed in China's imperial government. This interpretation is extended today to all U.S.-born children, regardless of parents' residency or legal status.

15th Amendment

Although African Americans became citizens under the 14th Amendment in 1868, they did not receive voting rights in any state until two years later with the 15th Amendment (1870). It banned racial discrimination or discrimination based on status as a former slave at the polls. The Enforcement Act of 1870 outlined penalties for violators of the amendment, including a $500 fine payable to the offended party.

The amendment might seem unnecessary because today, citizenship and voting go hand-in-hand. But in postbellum America, states had far more leeway to set their own eligibility requirements. Race was not a protected class, so racial restrictions were technically legal. The 15th Amendment resolved this problem, but opened up a new set of problems concerning workarounds and legal challenges.

Even though the 15th Amendment appeared to give African American men an inalienable right to vote, in conjunction with the 14th Amendment's guarantee of equal protection and rights for all citizens, there were still question of whether voting was even a right. The Supreme Court ruled in the 1876 case Reese v. U.S. that the 15th Amendment did not give the right to vote. It only forbade racial discrimination against potential voters who met other criteria, meaning states could exclude African Americans through proxy measures.

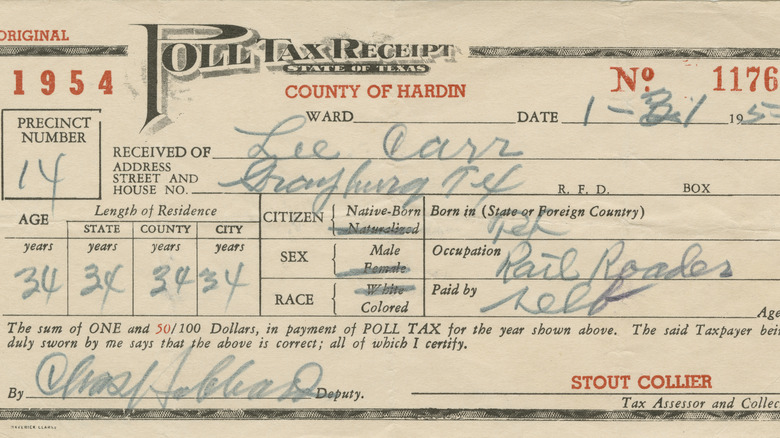

In the years following the ruling, states passed a flurry of laws designed to keep African American and poor white voters off the rolls. These included poll taxes that people could not afford, or difficult literacy tests that the uneducated could not pass. These would not be definitely overturned until the 24th Amendment in 1964.

16th Amendment

Americans hate taxes and the IRS. Before the 16th Amendment passed in 1913, however, no one had to worry about a filing deadline or audits – there was no permanent federal income tax.

Before 1913, Congress could only tax people directly (as opposed to indirectly with tariffs, excises, etc.) by apportioning the tax out to states by population, as written in Article I Sec. 9.4 of the Constitution. This meant that high-population states (not necessarily wealthier ones) would pay more, and it was never invoked. When the Cleveland administration tried ramming through an income tax in 1894, the Supreme Court struck it down the following year in Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.

To get its income tax to cover its increasing expenses, Congress proposed the 16th Amendment in 1909, which gave it the power to tax all income without apportionment. But it was a hard sell to the American public, so Congress marketed it as a matter of fairness. The tax, it argued, was to ensure the wealthy paid their fair share as the poor. Once it was ratified, the first federal income tax kicked in at 1% on incomes above $4,000 (average income in 1915 was $687).

Things did not remain that way for long, however. By 1918, increases had already hit, with the marginal top rates rounding 77% to finance World War I. By 1944, Franklin Roosevelt's administration had raised the top marginal rate to 94% and expanded the tax base to 90% of the American population, which faced a minimum rate of 23%.

17th Amendment

The 17th Amendment, proposed in 1911 and ratified in 1913, moved America away from a federal republican model of governance to a more democratic one through the direct election of senators by majority popular vote.

Before 1913, state legislatures appointed senators to represent state interests, namely by blocking overreaching federal laws. This ensured states could cancel out federal power and popular opinion, preventing America from becoming the Founders' worst fear – a pure democracy. George Mason Law Prof. Todd Zywicki argued the 17th Amendment undercut American federalism by removing a key check on federal power was lost because states could no longer use their senators to block federal legislation detrimental to state interests because they answered to the public.

Yale Law Prof. David Schleicher argued that the amendment was necessary because the Founders' original framework quickly collapsed due to partisanship, corruption, and politics. Although state legislatures appointed senators, the people elected their state legislators, who appointed senators reflecting public opinion. Special interests also factored in, tilting selection towards candidates who would favor their bottom lines. Schleicher argued that this "election-by-proxy" unnecessarily complicated matters when direct election would yield similar results.

Both scholars acknowledge that the appeal to direct democracy made the amendment widely popular. People supported it as a way to bypass corruption inside state legislatures by allowing the people to counterbalance the influence of special interests. Funnily, special interests and political machines supported it too, because they could game elections through increased turnout in cities they controlled. It went through, and still provides the framework for electing senators today.

18th Amendment

Prohibition and the 18th Amendment grew out of the 19th-century Temperance Movement, which had powerful allies such as President Rutherford Hayes and his wife Lucy. This movement initially campaigned against excessive drinking and its accompanying social ills rather than for the abolition of alcohol. By the 20th century, however, it had become a heavily Protestant movement advocating for total prohibition.

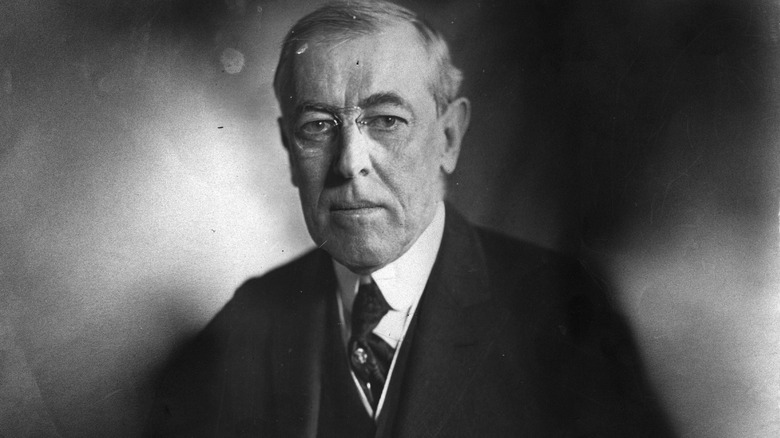

The Prohibition Movement achieved its goal with the 18th Amendment, passed in 1919. Contrary to popular belief, it did not ban drinking alcohol – it prohibited "the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within [and] the importation thereof" onto American soil. Alcohol was still legal, there was just no way to legally obtain it. The 1920 Volstead Act passed, despite Woodrow Wilson's veto, to create an enforcement mechanism for the law.

Prohibition opened up new problems relating to religious liberty, enforcement, and hypocrisy. When the Volstead Act carved out religious exemptions, Americans suddenly "found religion," or pretended to be clergymen. On Capitol Hill, hypocrisy abounded. Many of Prohibition's biggest supporters were kept supplied by Capitol Hill's personal bootlegger named George Cassiday. Ordinary Americans relied on organized crime.

Early 20th-century organized crime was a local affair of the usual street rackets like gambling and numbers. Prohibition was the perfect get-rich-quick scheme to go national. Gangsters such as Al Capone, Lucky Luciano, and Bugsy Siegel created sophisticated operations like the Chicago Outfit and Cosa Nostra to produce and smuggle illegal – and often tainted – liquor. The profits hired lawyers when the FBI or police came knocking. Born out of good intentions, the 18th effectively created the modern mafia.

19th Amendment

The 19th Amendment, which banned sex-based voter discrimination, was the natural result of Reconstruction-era constitutional reform. The 15th Amendment's ban on racial discrimination at the polls theoretically extended suffrage to most men as long as they met state requirements. Suffragettes argued that if voting was a citizen's right, then under the 14th Amendment's guarantee of citizens' rights, women also had the right to vote.

The Supreme Court ruled in the 1874 case Minor v. Happersett that although women were citizens under the 14th Amendment, citizenship did not confer automatic voting rights, which were set at the state level. Since voting was not a constitutional right, states could discriminate on sex – just as they had on race before the 15th Amendment.

In response, suffragettes lobbied to change state-level laws, finding the most success in the western states, nine of which granted female suffrage by 1912. But the easy national solution was a constitutional amendment banning gender discrimination at the polls. That year, suffragettes gained a powerful ally when former President Theodore Roosevelt and his Bull Moose party added women's suffrage to their 1912 platform.

With Teddy's endorsement, women's suffrage eventually got its amendment, which went the states in 1919-1920. As the end of the ratification process neared, Tennessee had yet to cast its decision. With the statehouse deadlocked, the tie-breaking vote fell to Harry Burn, an opponent of women's suffrage. But legend tells that his mother begged him to support the amendment. Out of filial piety, he voted yes, giving women the right to vote. His detractors accused him of selling out his vote.

20th Amendment

The 20th Amendment, passed in 1933 appears mostly an aesthetic calendrical change to the Constitution, moving the start of a new Congressional term to January 3 and a new presidential term to January 20. But it crucially eliminated the four-month period that could theoretically leave newly-elected officials powerless to respond to intervening crises.

Before the 20th Amendment, new presidents and congresses were sworn in on March 4, which worked fine as long as all was well in America. But, for instance, when Abraham Lincoln won the election of 1860, he was powerless to do anything to stop seven states from seceding between December 1860 and February 1861. Had the Confederacy chosen to fire upon Fort Sumter earlier than April 1861, Lincoln would have entered office while at war – hardly an ideal situation for a new president. Franklin Roosevelt had to postpone his New Deal agenda, despite crushing economic hardship among Americans, until March 1933, even though he would have liked to start immediately.

The reduced transition period allowed new presidents to quickly get to work rather than losing a crucial two months. Apart from changing the inauguration date, the amendment closed a handful of potential holes regarding presidential succession. Before January 1933, there was no hard rule for replacing a president-elect if he died before his inauguration. Before the 20th Amendment, had FDR been assassinated in February 1933 before his March inauguration, a potential constitutional crisis would have been on the cards. The 20th Amendment solved the problem by allowing the vice-president elect to serve as president until Congress could appoint a new one.

21st Amendment

The 21st Amendment, passed in 1933, ended Prohibition, which had been a total failure and made America's cities more dangerous. Congressmen and ordinary Americans flouted it, while organized crime got rich off of it. This brought two serious problems for American health and the rule of law.

The first problem was poorly-distilled illegal liquor containing methanol, which caused blindness and death when consumed. Time Magazine reported in 1927 that the U.S. government used this to scare Americans off drinking and into obedience of the 18th Amendment by spiking illegal liquor with the chemical. The consequences were thousands of American deaths.

Then there was organized crime. While 19th-century mafias focused on the usual illegal street rackets of prostitution, gambling, and protection, Prohibition offered gangsters the opportunity to go international, importing illegal alcohol from abroad for lucrative American black-market sales. Thus, corruption skyrocketed as mafias paid off everyone from customs officers to police and local officials to look the other way. By the late 1920s, virtually every Chicago public and law enforcement official, for instance, was in Al Capone's pocket. For yearly bribes totaling $250,000, Capone raked in $100,000,000.

The feds called it quits on Prohibition with the 21st Amendment, which repealed the 18th Amendment. Surprisingly, Utah, formerly a bastion of Prohibition due to the presence of the Latter-Day Saints Church, got the country over the three-fourths barrier to repeal. Although opposed to alcohol, many members of the church supported it, hoping legal drinking would pull the rug out from under organized crime. President Franklin Roosevelt signed off, and America celebrated.

22nd Amendment

The 22nd Amendment, which limits presidents to two terms, has only been in force since 1951. Before that, seeking a third presidential term was legal, even though American presidents almost always followed George Washington's two-term precedent. The first president to try breaking with tradition was Theodore Roosevelt, who ran for a third term (although his first term was due to an assassination not an election) in 1912 with the Bull Moose Party.

Teddy lost the election to Woodrow Wilson, so the precedent remained unbroken. It wasn't until Franklin Roosevelt won a third term in 1940 that Congress seriously considered presidential term limits. It was primarily a Republican concern due to the expansion of federal and executive power under FDR's New Deal. A 1940 pamphlet voiced GOP concerns that Roosevelt was turning the U.S. into a "one-man government" aided by an entrenched New Deal bureaucracy.

In 1946 elections handed Republicans a congressional majority. A Southern Democratic revolt against FDR and Harry Truman's civil rights sympathies gave the GOP 47 Democrat supporters (mostly Southerners) and the two-thirds majority needed to pass Joint Resolution 27, which put the 22nd Amendment on the table. Once it passed the senate Democratic infighting, once again from the Civil Rights fallout, got the amendment support from the Democratic Deep South, leading to ratification in 1951.

The amendment contained an additional provision aside from the two-term limit. If a vice-president became president through succession and served out two years or more of that term, it would count as a full term and he would only be allowed to seek one more.

23rd Amendment

The 23rd Amendment is a bit of a mystery to most Americans because it only affects the inhabitants of the District of Columbia. Historically, the district did not have electoral representation in presidential elections because it was not a state. It was (and still is) under Congressional purview, in accordance with Article I, Sec. 8.17 of the Constitution.

As U.S. law evolved and the district's citizens were subject to new obligations such as income taxes, they demanded more political representation (no taxation without representation!). Congress resolved in 1960 to give the District voting power in presidential elections, but not Congressional representation (even non-voting), through the 23rd Amendment. The law, ratified in 1961, gave Washington, D.C., electoral power as if it were a state equal to the smallest actual state. In practice, that meant three – one for each theoretical senator and representative.

As the District campaigns for statehood, the amendment has become a potential barrier to the cause because the Douglass Commonwealth – the new state that would be carved out of D.C. – would have three electoral votes. Meanwhile, a reduced federal district consisting of Capitol Hill, the White House, and other government offices would theoretically keep its three votes. Article I, Sec.1.2 of the Constitution, however, forbids anyone "holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States" from serving as an elector. This disqualifies the only theoretical residents of a reduced federal district – the First Family. To remove this barrier, Delaware Democrat Tom Carper has proposed repealing the amendment – a tall order given the politically charged nature of D.C. statehood.

24th Amendment

The 15th Amendment guaranteed the right of all male citizens to vote regardless of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude" (i.e. the formerly enslaved) and the 19th Amendment extended suffrage to women. But since states maintained their own voter eligibility rules, they found workarounds to stymie Black voting.

Among the rules was a poll tax – a common feature of the Jim Crow South that required potential voters to pay a cash fee to vote. The fees themselves were relatively low, but Black Americans, many of whom were indebted sharecroppers, often could not afford them and had to pay them regularly for two or three years before getting to vote. This advantaged white property owners, who were automatically billed for the taxes on their assessments. Poor whites, who also could not afford the taxes, were sometimes given suffrage through "grandfather clauses," which allowed anyone with a grandfather who voted before the Civil War to avoid the tax.

In response, Congress tabled the 24th Amendment, which forbade states from denying a citizen's right to vote for failure to pay any tax – including poll taxes. Interestingly, several Jim Crow states, including Georgia, voted for the amendment. Only Mississippi rejected it, and it became law in 1964.

Nevertheless, a handful of states refused to repeal their poll taxes, sending the amendment before the Supreme Court. The court ruled in the 1966 case Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections that poll taxes violated the 14th Amendment's guarantee of equal protection and were thus unconstitutional. A state could not restrict the rights of certain voters based on their ability to pay.

25th Amendment

America has had a few periods in time when the presidency was in a bit of limbo. Presidents like James Garfield and Woodrow Wilson spent months incapacitated, but not legally dead, meaning they technically continued to serve despite being incapable. Article II Sec. 1.6 of the Constitution specified that an incapable president could be removed if congressional declared the office vacant. Otherwise, the rules for presidential succession were vague.

After John F. Kennedy's assassination in 1963, the 25th Amendment cleared any doubts in cases of presidential disability or death. The first two sections stated that if a president died or resigned, the vice-president took over. If a vice-president died or resigned, the president nominated a new one.

The most important clauses are in sections 3 and 4. Sec. 3 explicitly required the president to transmit in writing that he was incapable of executing the duties of his office. If he refused, Sec. 4 gave the vice-president the power to intervene. If the vice-president and a majority of cabinet officers testified in writing to Congress that the president was incapable, the vice-president could take over until the president was deemed capable again, died, or resigned.

Although the amendment was written after the Kennedy assassination, the writers likely had Woodrow Wilson in mind. The president suffered a stroke in 1919, which left him half-paralyzed. But he would not resign, and Vice President Thomas Marshall would not take power without congressional authorization and a written declaration from Wilson. The 25th Amendment circumvented these problems, ensuring a smooth succession in the case of death or disability.

26th Amendment

During World War II, the United States reduced the draft age from 21 to 18 to expand the pool of potential manpower. This presented a problem: teenagers were now old enough to die but not old enough to vote – that age was still 21. It became a key issue during Vietnam, as young people argued that if politicians could draft them to war, they should have a chance to vote them out. In 1970, Richard Nixon addressed these concerns with an amendment to the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which lowered the national voting age to 18.

As the president expected, the states challenged the amendment at the Supreme Court in 1970 in Oregon v. Mitchell. Justice Hugo Black delivered the majority opinion, writing that the court was upholding the amendment insofar as applied to national elections for offices like the presidency. If 18 year olds were expected to shoulder the duties of citizenship, they were entitled to equal protection under the 14th Amendment, which guaranteed them their rights as U.S. citizens. By the 1970s, that included voting in federal elections. But, SCOTUS ruled, Congress and the Executive Branch could not dictate age requirements for state and local elections.

The 26th Amendment resolved the constitutional problem by banning age-based voter discrimination against American citizens over the age of 18. It was proposed on March 23, 1971 as a way to bypass the Supreme Court's decision, flew through Congress, and was ratified by July of the same year – much faster than virtually every other amendment, which had often taken years to get through.

27th Amendment

The 27th Amendment forbids congressional pay raises from taking effect until after an election has taken place. Unlike the other amendments, which were proposed to meet specific issues and close gaps in the Constitution as they arose, this one passed Congress in 1789, but did not take effect until 1992.

Per the Constitution Center, at the heart of the amendment was a debate at the 1787 Constitutional Convention over public servants' pay. Benjamin Franklin wanted to nix all Congressional pay, arguing that politicians should not have any opportunity to get rich in office. The Convention, however, approved Congress' power to set its own salaries. In response, James Madison proposed, alongside 11 other amendments, an amendment that would prevent the raises from taking effect immediately. He reasoned that if an election took place first, a public unhappy with the salary raises could vote the guilty parties out, denying them the benefit of the raise.

While 10 of Madison's amendments became the Bill of Rights, the one that would become the 27th Amendment only got six votes from the original 13 states (10 were needed). But since there was no expiry date on the legislation, it sat there in limbo into the 20th century without the necessary votes for approval.

By 1982, congressional approval had cratered as Americans discovered the various perks and high salaries Capitol Hill politicians enjoyed that ordinary Americans could only dream of. After a college student brought the amendment to national attention, a campaign for ratification, motivated by Congress' largesse, got it through in 1992, when 38 states ratified it.