What It Was Really Like Being A Coal Miner In 19th-Century America

Practically no one thinks that coal mining is an easy job. Even today, it requires miners to venture deep underground and use heavy machinery to extract coal from the rock. But what was it like more than a century ago? In 19th-century America, miners had it even tougher. They often worked in isolated places with fewer safety considerations and less-advanced technology that demanded strenuous physical labor. They were also under growing pressure to supply coal to a quickly-growing nation while facing off against supervisors and mine owners who didn't always have their best interests at heart.

However, there was room for some surprises in the mining industry, given changing attitudes on race, ethnicity, gender, and child labor. And while we may associate the dramatic face-offs between unionizing miners and their company overlords with the early 20th century, the truth is that the mining labor movement got its start far earlier. This is the reality of being a coal miner in 19th-century America.

Some early coal seams were relatively easy to mine

In the early decades of the 19th century, coal mining was maybe easier than you'd think, as American miners were more likely to be working at surface seams, especially in the rich coal fields of Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Ohio. If miners were lucky enough to land a spot alongside rivers, such as the Monongahela near Pittsburgh, they might even be able to roll coal carts down a riverbank and straight onto a ship for transport.

While this allowed workers to at least see the sun, no one was lollygagging. Teams of laborers headed by more skilled miners were expected to pull tons of coal out of their mine. As industrialization contributed to the spread of cities and the upswing of industry, miners were pushed to pull ever more coal out of the ground to fuel all this growth. In 1850, miners working in Ohio produced an estimated 320,000 tons of coal. In 1853, that amount increased nearly fourfold to 1,300,000 tons.

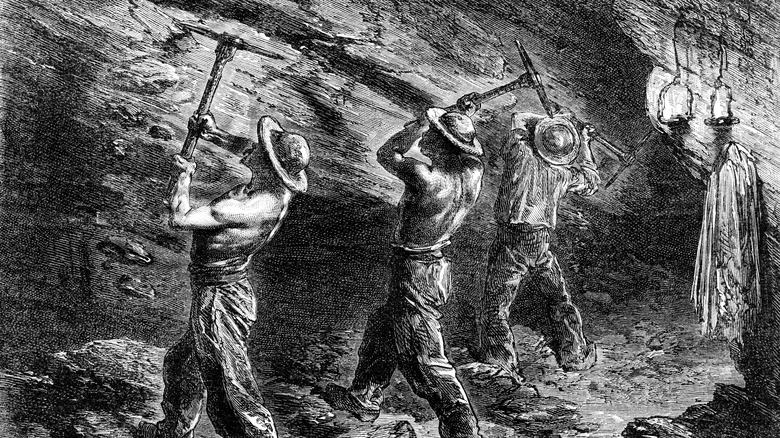

Mining demanded serious physical labor

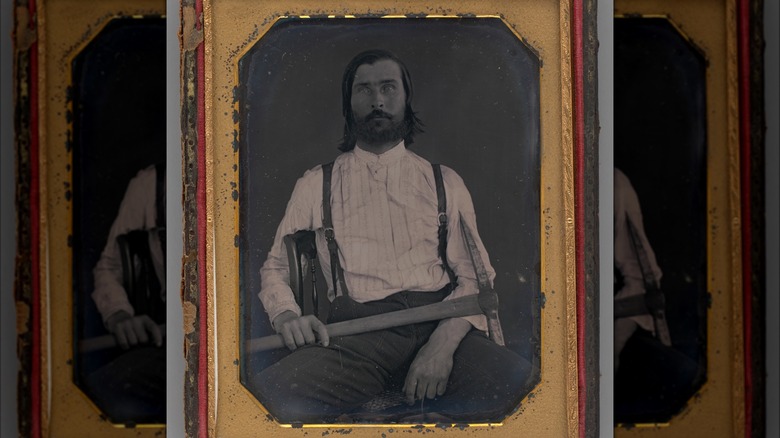

American miners of the 19th century had no choice but to work hard. Sure, they would have reached for tools like wheelbarrows and pickaxes, but these were all still powered by the physical labor of workers who hefted these weighty tools hour after hour and day by day.

When American demand for coal grew more intense, miners started to move underground, chasing seams of relatively soft bituminous coal and, increasingly, harder anthracite coal. Digging new chambers underground, a process known as undermining, was some of the most backbreaking labor involved. It required miners to cram themselves into small spaces and, by striking the rock as hard as they could, eke out a new extension of their mine.

The initial phases of undermining required workers to push themselves into awkward stances to strike the rock, which surely irritated or even led to joint issues and lower back pain. Sometimes, miners had to lie down in order to get at a seam of coal. The work could be somewhat easier if the ground was soft, but it still required about 40-50 swings of a pickaxe per minute, as Andrew Roy estimated in 1885's "The Practical Miner's Companion."

Miners faced serious health risks

Just between 1880 and 1923, over 70,000 miners died at work from causes such as mine collapses, methane explosions, and deadly encounters with machinery. For convict laborers forced to work in mines, things could be even worse. Poorly-fed, oftentimes abused prisoners were crammed into close proximity and suffered waves of communicable diseases as a result.

The above figure doesn't include deaths from the long-term effects of mining, either, like the debilitating and sometimes deadly disease known as coal worker's pneumoconiosis, often known by the more blunt name of black lung. In 1831, Scottish doctor James Craufurd Gregory was the first to link the inhalation of coal dust and blackening of the lungs, which he noted during the autopsy of a coal miner.

Despite the early descriptions of the disease and attempts to mitigate it, mine operators and public health officials often turned a blind eye to its effects. Well into the 20th century, some American doctors and mine owners were still questioning the existence of black lung, though it had clearly been plaguing coal miners for generations.

Early unions fizzled

Because so many coal mining operations before the American Civil War were small, independent, and in relatively rural places, hopeful labor organizers faced serious obstacles based on communication issues alone. In some places, owners even worked in their mine alongside other laborers, perhaps making it more difficult to pick them out as a more distant enemy as later miners would do.

As coal mining became a more profitable and organized industry, it allowed for the rise of potentially exploitative systems in which mine managers, focused as they often were on efficiency and profit, underpaid miners and neglected their safety. Labor organizers carried the threat of costly strikes, increasing the tensions between those who owned mines and those who worked them. Plus, as later owners and managers were more likely to stay out of the mine altogether, those who actually went underground to risk their health and safety more easily saw them as adversaries.

Even so, the earliest attempts to unionize miners often proved to be duds. In the 1840s and 1850s, American miners occasionally went on strike for higher wages, but they were either dissuaded by armed security forces or their wins didn't go beyond their own mines. Because so many mining operations before the American Civil War were relatively isolated, brewing labor movements often got tamped down in a short period of time.

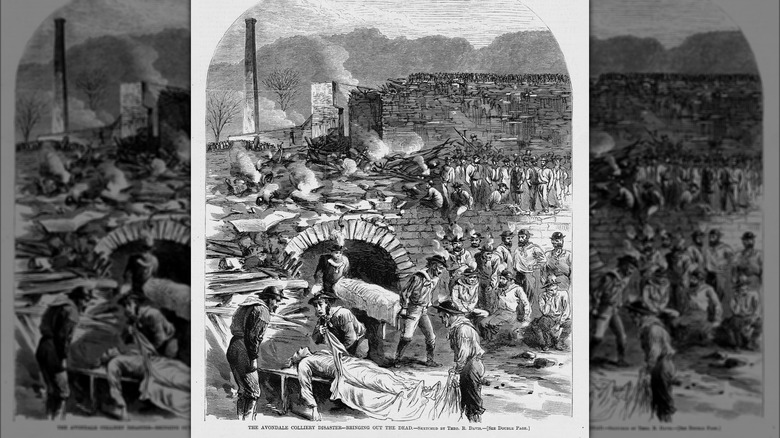

Post-Civil War mining became more dangerous

As the nation grew in the decades after the Civil War, miners had to dig ever deeper to find coal. This necessitated a move from open pit mines that pulled coal from seams relatively close to the surface, to deeper shaft mines. Some in Pennsylvania went as deep as 1,500 feet by just the 1860s.

This brought a bevy of new hazards. Deep mines needed to be ventilated, especially because was often found in association with flammable methane gas. On an especially bad day, enough methane couldm even cause a mine explosion. Miners also needed to pump groundwater out of the tunnels. If a pump system failed, anyone inside the mine could stand to drown in the dark recesses of the mine.

Then, there was fire. In an era before widespread electricity, tools such as water pumps were powered by furnaces. Support structures in the mines were made out of wood, which could potentially catch fire. Besides increasing the danger of collapse, burning timbers could also consume oxygen inside the tunnels and suffocate miners. This was the source of the 1869 Avondale mine disaster in Pennsylvania, in which a ventilation furnace started the fire. The ensuing conflagration not only collapsed timbers and depleted much of the oxygen in the mine, but blocked the only exit. After two days, rescuers found 108 fatalities inside. Two rescuers had died in the attempt, as well.

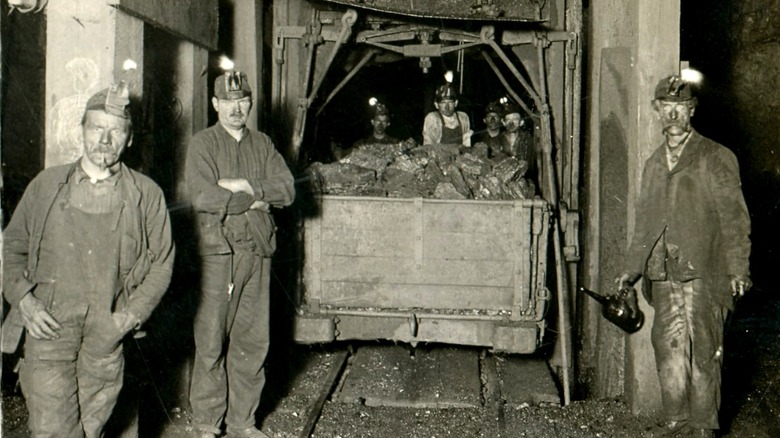

Miners needed to have a good handle on technology

Though miners were working with things like old-fashioned open-flame head lanterns well into the 20th century, in other respects they worked fairly closely with technology, especially in the years after the American Civil War. More and more devices began to appear in deep mines to manage important tasks like bringing fresh air down into the mine and pumping out the ever-present groundwater. Initially, these machines worked under steam power, though electric pumps began to appear in mines during the final decades of the 19th century.

Towards the end of the century, miners were increasingly likely to use machines that took on some of the manual labor once done by a collection of men with hand tools. These eventually included machinery that took on the uncomfortable work of undercutting coal seams, extracting coal, and transporting it to the surface. If anyone felt a pang for the days of carts pulled around by mules, they likely didn't have much time to wax nostalgic. Demand for coal kept growing, and so did productivity goals for mines and pressure on the miners.

Some coal miners were convict laborers

While the 13th Amendment to the Constitution banned slavery in the United States in 1865, it contains an exception for convicted criminals. Tellingly, many prisoners in the post-Civil War era were people of color. In 1866 Tennessee, 52% of prisoners were Black. In 1891, that number was a staggering 75%. Many Black prisoners were incarcerated after being convicted of minor, even inconsequential, crimes such as theft or simply being unemployed.

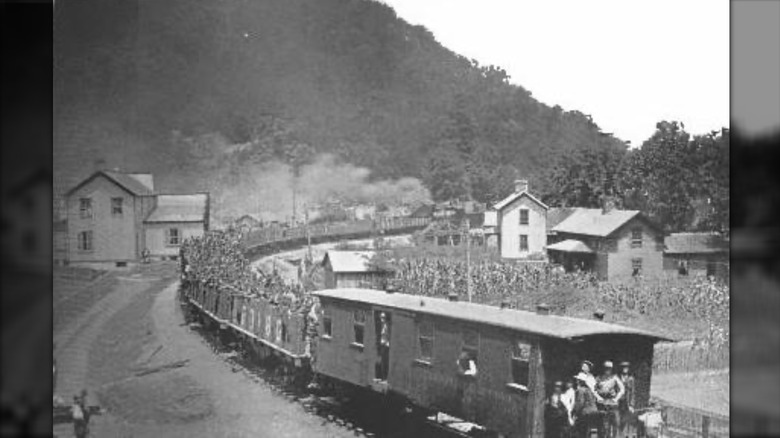

Many states turned to a practice known as convict leasing, in which prisoners would be hired out to work in places like coal mines. In Tennessee, the Lone Rock prison stockade saw convicts forced to work to the benefit of the Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad company, beginning in the 19th century.

In July 1891, miners at the Tennessee Coal Company in Anderson County protested the use of convict labor in place of paid, unionizing miners, releasing convicts (most of whom were Black) from their stockade. The governor and a militia traveled to the mine and promised that the state government would reconsider the use of convict labor. When it failed to do so in August, miners revolted, arming themselves and releasing hundreds of prisoners in what came to be known as the Coal Creek War. Though the miners were eventually apprehended, the harsh reality of the convict conditions changed public opinion and the lease system ended (in Tennessee, anyway) in early 1896.

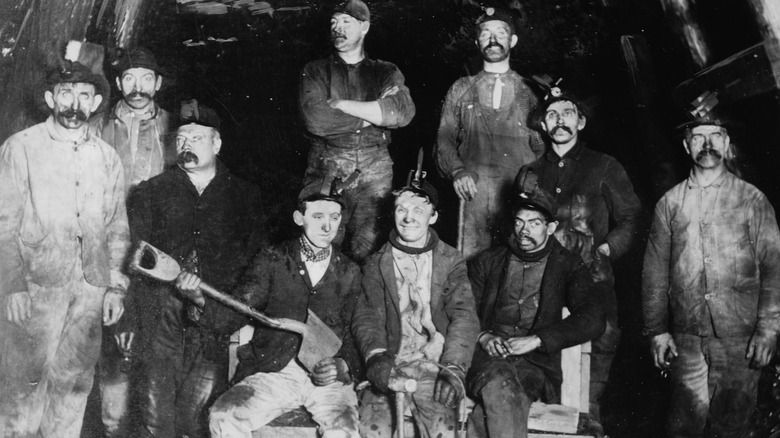

Black miners faced opportunity and discrimination

From practically the beginning of American coal mining, many of the people undertaking the work were Black Americans. Prior to the Civil War, a significant number of these laborers were enslaved people, like those who worked the open coal pits near Richmond, Virginia. While the end of slavery technically opened more avenues for Black miners to earn money, the complicated realities of segregation and racism meant that many were still confined to work as unskilled laborers in mines. However, some mines in places like Helen, West Virginia provided opportunities to work relatively free of supervision and restriction, which surely appealed to Black miners who had no desire to replicate the old ways of working under all-too-close supervision.

Two decades after the turn of the century, more than 25% of miners were Black in some regions of Appalachia. Given the mines' need for workers, white and Black miners could find themselves working in close proximity. While this was hardly a situation where everyone held hands and sang in harmony — in fact, some owners hoped everyone would be too busy butting heads to unionize — it proved to be a unique experience for almost everyone involved.

Many miners were far from home

Though the use of imported coal from Britain had declined to practically nothing in 19th-century America, that didn't mean the relationship between the two nations' coal industries was completely severed. That's because, in the 19th century, quite a few of the miners working in American coal mines were immigrants from coal mining regions of the U.K. They were especially in-demand if they had previous experience in mines, a valuable asset in an era before formally-trained mining engineers became fixtures of the industry. Some immigrants were also hired on as less-skilled laborers, including Irish people who were fleeing the Irish Potato Famine in the mid-19th century.

Other immigrants began to take up work in American coal mines, too. A report delivered to Congress in 1911 noted that by the late 1800s, coal miners in West Virginia could be from a number of European regions, including parts of Italy, Poland, and Croatia. The report maintained that, since "many of the better class of American miners" had left for other coal fields, West Virginia mines had to not only accept immigrants but actively work to attract them and so address the region's labor shortage. By the turn of the 20th century, signs posted in mines could contain many different languages, speaking to the number of non-English-speaking immigrants who had already established themselves in the coal industry.

Women sometimes mined, but rarely

Though the world of mining, especially in the 19th century, was a very male-dominated one, it wasn't completely devoid of women. As researcher Jason Sampson uncovered, records for Stark County, Ohio showed that at least four women between 1870 and 1880 worked as coal miners. Their exact duties remain unclear, but they may have worked as part of a family-based operation in which women were occupied with work like loading coal carts and bringing them out of the mine (as opposed to actually mining coal from a seam in the rock).

Financial and social pressures sometimes pushed women to take on more physical labor in the mines. Born in 1870 Ohio to a poor and large family, Mary McBride began working in the mines at the age of just eight. She almost certainly took on work reserved for young laborers, such as opening and closing mine doors for coal carts. Other 19th-century women took on work alongside coal miner husbands or other family members, going into the mines to load coal and ease the financial woes that threatened their households. However, they appear to have remained the exception, especially as mines were increasingly run by companies and not independent operators.

[Featured image by Wellcome Images via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 4.0]

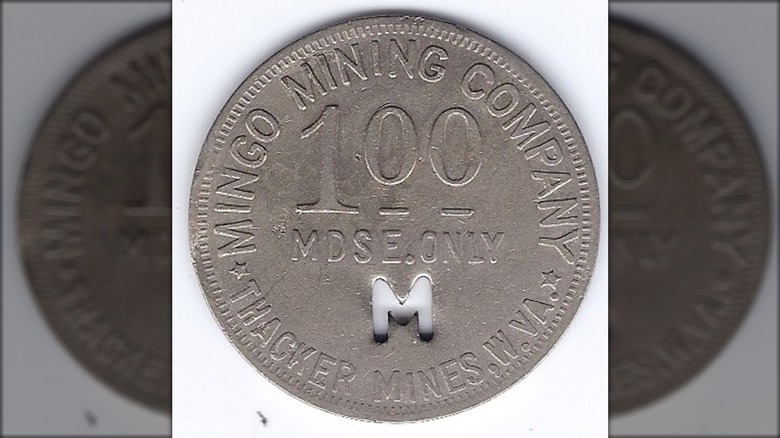

Scrip could put miners in a difficult situation

In some isolated coal mining towns, miners were not paid in money, but in company tokens that came to be known as scrip. Though the vouchers, which could come in the form of metal coins or coupon-like booklets, could be redeemed at company-owned stores, they were initially worthless anywhere else. This system was partially born out of geographic necessity, as 19th-century mining operations in Appalachia or other rural areas were far from cities or even small towns that could have competing stores. This was even more true in an era before railroads came to town and made transport somewhat easier. Before all that, the only supplier of necessities like food, clothing, and mining tools was the company itself.

But the scrip system could turn exploitative, with mining companies charging employees and their families for basic supplies and transportation before they even started work. The debt was sometimes all but impossible to pay off and made it all the more difficult for miners to get hold of cash and work their way out of poverty. Troublemakers — like anyone who started talk of unionizing — could also find that their line of credit at the company store had suddenly been cut off. Starting at the end of the 1800s and continuing into the 20th century, numerous laws limited the scrip system, while the U.S. Supreme Court determined that scrip had to be able to be turned in for money in 1918.

[Featured image by Coal town guy via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

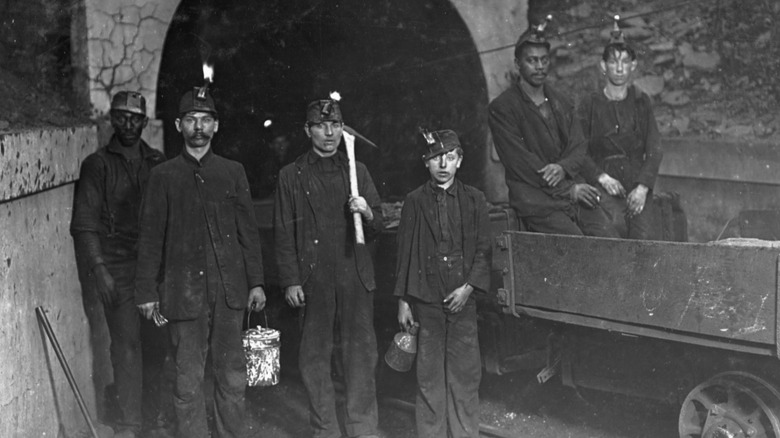

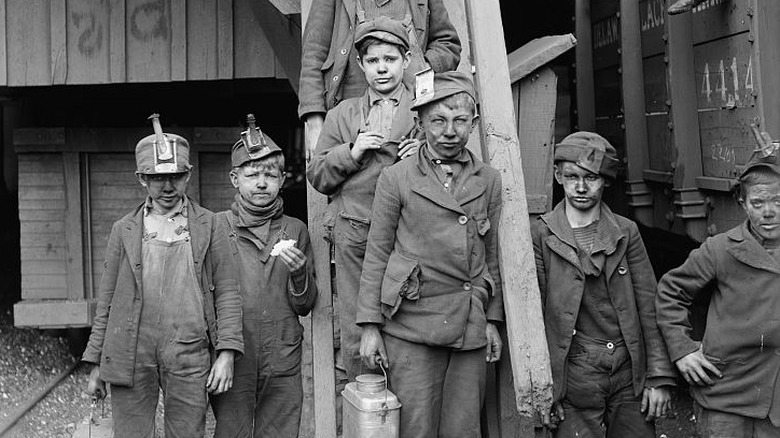

Some mine workers were children

If you were to enter a 19th-century coal mine, you would come across plenty of adult men working there. But you would also have to remember to glace down, as some of the workers in the mine would be children. By the 1800s, American children were often put to work in many places, though child labor laws were beginning to regulate the sort of jobs they could take and number of hours they could put in. Yet, economic pressures and social convention still often pushed young boys (and the very occasional girl) to make their way down into the mines to help support their families.

While few records indicate that children were swinging pickaxes or operating other tools to remove coal from the rock, they took on other roles. Many found employment as breaker boys who would remove waste from mined coal as it hurried past them on a conveyor belt. Others sat by mine doors, opening and closing them for coal cars, while boys in pre-mechanization mines could be found driving the mules used to pull carts around. Some acted as assistants to adult miners, especially if the miner in question was a relative or working as an independent journeyman. Practically all were expected to work long hours in punishing, dangerous conditions. Certainly, none of the children working in mines were where reformers thought they should be: at school.

Unionizers got a second wind at the end of the century

As the 20th century approached, many miners were increasingly unhappy. Long hours, low pay, the exploitative scrip system, and more contributed to the second rise of mining unions. These included the rather passive Workingmen's Benevolent Association (WBA) in 1868, formed largely by British, Irish, and German immigrants. But not everyone was ready to play nice.

Amongst Irish-American miners, the group known as the Molly Maguires became notorious for allegedly violent reprisals against mine operators. Taking cues from earlier Irish secret societies, the American Molly Maguires targeted owners, managers, and scabs who worked despite strikes. Their tactics were said to include death threats known as "coffin notices", beatings, and assassinations. In 1870s Pennsylvania, 24 mine supervisors were allegedly killed by members of the Molly Maguires. A private investigator's testimony during the subsequent court trial contributed to 20 death sentences, including 10 carried out on June 21, 1877. However, historians now believe that the trial was sensationalized and the sentences were not fairly handed down. Few accept that the Molly Maguires were as organized as 19th-century fears would lead one to think.

The dramatic downfall of the Molly Maguires gave anti-union figures fuel to effectively dismantle the WBA, but other unions soon arose in its place. In 1890, the national United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) formed and gained many members after high-tension mining strikes broke out in 1897, setting the stage for the mine labor conflicts of the 20th century.