Inside Leonard Bernstein's Complicated Relationship With Felicia Montealegre

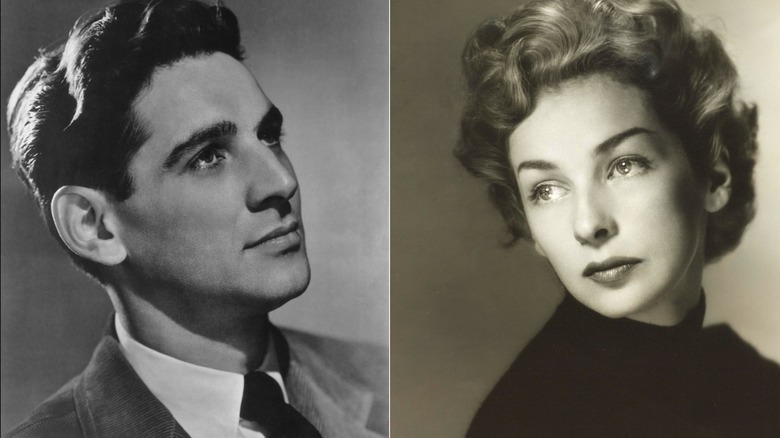

It sounds like a story from the pages of a fairy tale, but it wasn't — it's from the pages of Meryle Secrest's biography "Leonard Bernstein: A Life." It starts (this part, at least) with Felicia Montealegre y Cohn, a Costa Rican-born, Chilean-raised beauty, accustomed to a life with servants but determined to head off to a Bohemian existence in America. And that's exactly what she did, although her life in the U.S. wasn't exactly a struggle: She was taken under the wing of a family friend, who would introduce her to one of the era's most influential, up-and-coming conductors and composers.

She'd heard of Leonard Bernstein before and laughed away suggestions that they would be a perfect match. When she attended a performance at New York's City Center, however, she reportedly told her closest friends that she would, in fact, marry him. She described the meeting as leaving her "completely bowled over. It was such a mixture of things. It's very rare that people see and meet someone with whom they feel they are destined to share a life ... The incredible thing was that he felt the same way about me as soon as we were introduced."

Lovely, for sure, but the relationship and marriage that unfolded over the following decades was tumultuous, complicated, and rarely easy. Money and fame, it turns out, don't necessarily make personal lives effortless: Let's look at the true story of a complicated yet loving relationship that tragically didn't have a fairy tale ending.

Marriage difficulties were foreshadowed during their courtship

The early days of a relationship are the most likely to be a whirlwind of romance, but that wasn't necessarily the case for Felicia Montealegre and Leonard Bernstein. Montealegre's friend, Bethel Leslie, offered her observations of the early days of their relationship in Meryle Secrest's biography, "Leonard Bernstein: A Life," and said that while they were a good match on paper, "There was a large part of him that was very much the small boy in those days, and she was the grown-up, responsible one. As for their being madly in love, I would have thought they were in love with what the other person was, but not who."

That's a big difference, and according to friends who witnessed the start of the relationship, it wasn't an easy one from the start. They were immediately long-distance — which was made even more difficult by the fact that she didn't have a phone, and they needed to coordinate conversations via telegram — and even from those early days, friends say that she was discouraged by the instability of the relationship.

By the end of the year, though, things seemed to get on track and friends say it seemed as though they were wrapping up 1946 on a high. Montealegre was officially a professional actress, and Bernstein headed out to spend a month with her at the 40-acre ranch house belonging to some friends. There was talk of marriage and love, but it was complicated.

They got engaged ... twice

Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre got engaged very, very quickly. In his biography, "Leonard Bernstein," Humphrey Burton writes that they had only been exclusive for about a month when they announced their intent to marry. While Bernstein's father was happy for the young couple — and only requested that she convert to Judaism — his mother wasn't shy about expressing the opinion that he could do better. Bernstein's lifelong assistant, Helen Coates, was also less than thrilled. Even as she spoke with Montealegre and reassured her with her blessing, she gave public interviews, stating, "Music comes first and it always will. If he ever does marry, his wife will have to recognize that from the beginning."

By 1947, the rumor mill was churning: Bernstein, it was reported, had a new girlfriend. The proposed date for a wedding had come and gone, and he was regularly seen in the company of the teenage Ellen Adler. He had apparently talked about wedding bells with her, too, but she was in Paris by the following year.

That's not to say that he had completely forgotten about Montealegre, and they were occasionally seen out and about in each other's company. Still, Bernstein traveled — through Europe and Mexico — and it took until 1951 for the couple to fully reconcile and announce a second engagement.

Leonard Berstein's male companions were an ever-present part of their relationship

Even though Felicia Montealegre made it clear from the beginning that she intended to marry Leonard Bernstein, his immediate response to meeting her was less certain. According to Humphrey Burton's biography, "Leonard Bernstein," he left New York City the day after meeting her, and he wasn't alone. He wrote a series of letters that referenced a man named Seymour, who joined him both in San Francisco and later in Vancouver. "This is a heavenly evening," he wrote in one. "S. and I have made no appointments, but have remained in the room with dinner and talk and reading and writing and infinite love. These days have been beautiful beyond belief."

One of Bernstein's many loves — an Israeli soldier named Azariah Rapoport — visited him in New York City, and was neither the first nor the last man to be associated with him. Bernstein's sister, Shirley, has talked about his struggles in both settling down and coming to terms with his sexuality.

In Meryle Secrest's "Leonard Bernstein: A Life," Shirley shared that in the lead-up to the marriage, "He had had a lot of therapy by then, to accomplish one thing or another. He wanted to be at peace with himself, either as a homosexual or a heterosexual." She said that he was fully aware of what he called his "darker impulses," and given that he also believed marriage was a lifelong commitment, he struggled to reconcile the two.

The wedding wasn't exactly drama-free

Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre were married about a month after announcing their second engagement. Although Bernstein's public comments seemed to suggest they simply hadn't seen the point in a long engagement, it was a hectic whirlwind behind the scenes — and it was one that followed a week-long bachelor party in Cuba. When Bernstein and his brother returned from their trip, it was to a wedding-day eve dinner, which Burton Bernstein summed up in Humphrey Burton's biography, "Leonard Bernstein."

"Everybody was on edge. Lenny was so nervous. Felicia was coming to dinner. My parents were sort of half-thrilled that she was half-Jewish. Shirley [Bernstein's sister] and I realized that it was going to be a nightmare dinner." They got through it with the help of some joke-store pranks, but tensions were so high that he added, "We often thought the wedding took place merely because of that evening."

Even on the day of their wedding, not everyone was interested in getting along. Her Catholic, aristocratic family was at odds with his Ukrainian, Jewish family, and the fact that they immediately got lost when they set off on their honeymoon was about par for the course. They did, however, make it to Mexico after a meandering trip that included Schenectady, New York, and Cheyenne, Wyoming. Along the way, Bernstein wrote a letter that included the sentiment, "It gets better all the time — I think we'll make it."

The first baby followed very quickly

For as quickly as Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre made the decision to get married after their second engagement, it seems as though they skipped a few important conversations: Although Meryle Secrest's biography, "Leonard Bernstein: A Life," recounts his assurances to a reporter, that, "... from now on, my bride will be Mrs. Bernstein and will forget she was Miss Montealegre," she absolutely did not take the name "Bernstein." Still, they were still on their year-long honeymoon when they announced she was expecting their first child — which, again, seemed to come before a few crucial conversations.

Leonard's father, Sam, made it very clear throughout the pregnancy that he was hoping for a boy, and the pressure went over about as well as could be expected. When she gave birth to a girl, they had originally agreed on the name Nina. Leonard, however, reportedly vetoed the name at the last minute, and insisted on naming their little girl Jamie. She protested, but relented.

Montealegre would get to use the name she'd wanted for their third child, born in 1962 — a decade after the first. In between was Alexander, born in 1955, and although Bernstein loved his children, his parenting skills weren't without reprimand: Montealegre reportedly observed, "He plays too hard, throws them too high, squeezes them too tight."

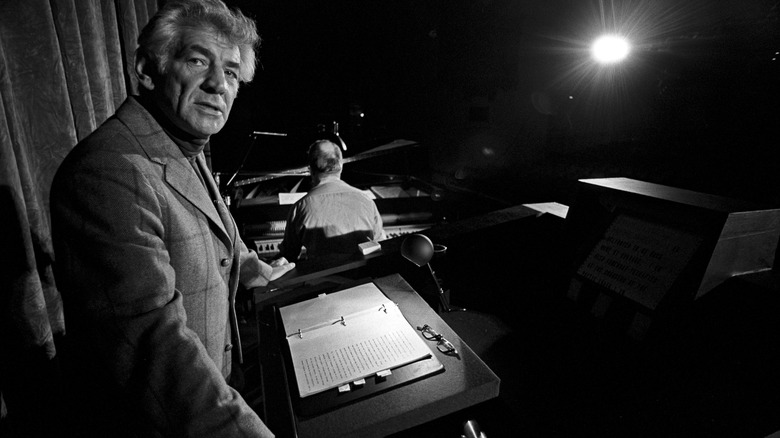

The summer of 1967

In 1967, Leonard Bernstein, Felicia Montealegre, and their three children spent the summer at their Italian villa. They were joined by John Gruen (along with his wife and daughter), and Gruen documented the long vacation in his book, "The Private World of Leonard Bernstein." It provided an unprecedented look at Bernstein's personal life, and although Gruen stressed that there was no set schedule, Bernstein still came equipped with goals — specifically, composing. But there were, however, plenty of other activities to be done in between: daily swimming, boating trips, long drives through the surrounding countryside, and — of course — music.

Gruen says that although they were surrounded by staff, they very rarely had outside intrusions into their Italian paradise: Those that were invited to dinner and parties were family and longtime friends, as they not only turned down most invitations, but they reportedly loathed parties and had instructed their staff to courteously yet firmly decline them. Among the guests welcomed to the villa, however, were Charlie Chaplin, his wife, Oona, and two daughters.

Reflecting on Montealegre's state of mind, Gruen painted a picture — even as she painted his portrait — of a private person struggling with private thoughts. "The household word that is Leonard Bernstein almost makes her shudder," he wrote, but added that there were "good times with Lenny and the children, visits from good friends, the sea and pool to compensate for some of those negative feelings."

A dinner party and fundraiser defined their image

Leonard Bernstein and his wife Felicia Montealegre shared a lot of things, including their left-leaning political views. For example, they supported the Kennedy family but didn't support the Vietnam War. When Montealegre learned that a group of Black Panthers were arrested and waiting in jail for their trial, after a wildly disproportionate bail had been set, she decided to do something about what she viewed as a miscarriage of justice. What started out as a meeting turned into a who's-who gathering of artists, attorneys, members of the Black Panthers, and activists getting together over cocktails ... and although the press wasn't actually invited, they made it in anyway.

The resulting article from journalist Tom Wolfe coined the term "radical chic," and caused a massive scandal. The New York Times went as far as to run a story (via The Leonard Bernstein Office) saying, "[The event] represents the story of elegant slumming that degrades patrons and patronized alike. ... It mocked the memory of Martin Luther King Jr."

It kicked off a massive campaign that started with hate mail and spiraled into FBI surveillance, and in 1980 — a full 10 years after the party that had caused so many problems — Bernstein was still outraged. He issued a scathing statement through The New York Times and wrote (in part) that although he claimed it hadn't had the negative impact on his career he believed some people had wanted, "they did cause a good deal of bitter unpleasantness, especially to my wife who was particularly vulnerable to smear tactics."

Bernstein eventually left her for a radio station music director

Leonard Bernstein's extramarital affairs were an ongoing thing, and in 1971, he was introduced to a man that he would fall completely and utterly in love with. Tom Cothran was the musical director for a California radio station, and met Bernstein during one of his trips to the West Coast. In Humphrey Burton's biography "Leonard Bernstein," Harry Kraut (then of the Boston Symphony), recounted Bernstein trying to drive and tell him about his new love: "He got more and more excited about this boy he had met in San Francisco with whom he was madly in love, and the car went slower and slower until it stopped moving altogether, right in the middle of Route Seven."

Bernstein was 53 at the time, and had been married for 20 years when he met the 24-year-old Cothran. Burton suggests that until Cothran, Bernstein's affairs had been largely physical, and not only did Bernstein enter into a deeply emotional relationship with Cothran, but he introduced him to wife Felicia Montealegro and their children. Initially, everyone got along to the extent that Cothran was welcomed as a part of the extended family. Years passed, and by 1976, they were regularly traveling together.

Things came to a head at their son's 21st birthday: Montenegro gave her husband an ultimatum, and told him that he needed to choose between her and his lover. Bernstein chose Cothran, moved out of his home, and his daughter learned about her parents' split from the newspaper headlines.

They reunited even as she received a heartbreaking diagnosis

Leonard Bernstein's sister, Shirley, participated in Meryle Secrest's biography "Leonard Bernstein: A Life," and explained his difficulties with relationships: "He'd have this fling thinking he had found the love of his life, but then he would always end up discovering this wasn't 'it.'" Felicia, however, was always there for him, and in 1977, he had left Tom Cothran and moved back with his wife. Friend Rose Styron confirmed that it was a difficult situation for both: "I think he tried awfully hard. Felicia was always very discreet and loving and not bitter ... [but] I think she had heard it all once too often."

It was about the same time that Montealegre developed a nagging cough that was then diagnosed as lung cancer. Her death was long and painful: Multiple attempts at treatment failed, and Bernstein's method of dealing with her decline was described by friends as bizarre and uncomfortable — most of all, for her. Those who saw her near the end of her life recalled her being very, very ill: "She was sitting there unrecognizable ... She did not say a word, but she was looking at Lenny with immense dislike, almost hatred."

Another recalled: "Felicia was in the hospital and Lenny proceeded to graphically describe her illness, including how many organs she had lost." When it became clear that she was in her final months, Bernstein moved her to a new house on Long Island, canceled his professional commitments, and remained by her side.

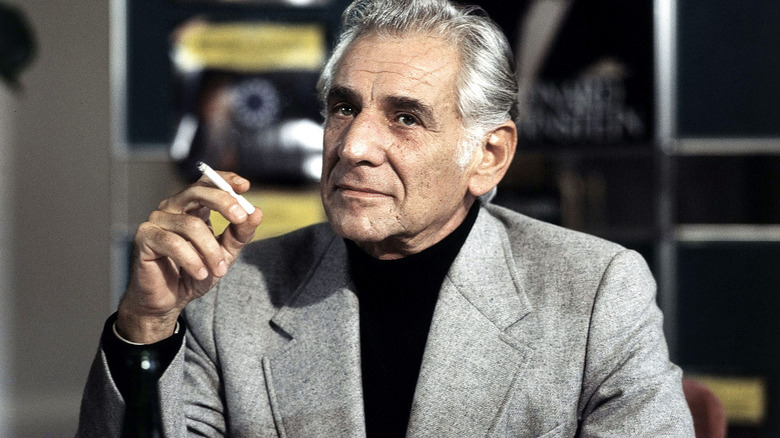

Leonard Bernstein struggled after Felicia Montealegre's untimely, tragic passing

Felicia Montealegre passed away on June 16, 1978, and Leonard Bernstein found himself facing the most profound struggles of his life as he tried to figure out how to go on without her. He wrote (via Meryle Secrest's "Leonard Bernstein: A Life") of a grief that only the grieving can understand, of "the kind of insomnia when you can't work, you can't read, you don't know what to do with your body, your muscles tickle and everything itches. But during the day I slept nonstop, to avoid living. ... I thought I was finished."

Friends, too, worried, and shared stories of a Bernstein who didn't sleep, who greeted friends in restaurants then went off to eat alone, who surrounded himself with photos of her, converted her bedroom into a study, who spoke of reincarnation, of hearing her, and of even seeing her.

His grief was so complete and so public that there were those who thought it was just for show, but when some realized how all-consuming his most dangerous behaviors — chain-smoking, drinking, and long nights without sleep — were getting, they knew it was serious. It was Aaron Copland who said, "Lenny wants to die." He, however, did not: Not until 1990.

The letter that explained everything

Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre weren't alone in their relationship, of course: It was their oldest daughter, Jamie, who has since been the most public when speaking about what it was like to grow up with her famous parents. How much did they know about their tumultuous relationship?

When Jamie spoke with NPR around the release of her biography, "Famous Father Girl: A Memoir of Growing Up Bernstein," she said that they had grown up hearing rumors. She was a senior in high school when her father moved in with Tom Cothran, and said, "By then, it was pretty clear what was going on." Still, she says that they just didn't talk about it, and when her father died, she and her siblings found some answers in letters they left behind — specifically, a letter that her mother had written, indicating that she accepted him for who he was.

"To know that her eyes were wide open about this marriage and what she was getting into, that was amazing to discover," Jamie shared. "It said a lot about our mother that she would write this letter to our father and say, "Look, you know I get it. It's complicated. But let's do this because we love each other. Let's make a family and go forward.'" Jamie is well aware, too, that it wasn't easy: "I think she bit off more than she could chew," she said. "And it makes me very sad to contemplate it."