The Untold Truth Of Bob Dylan

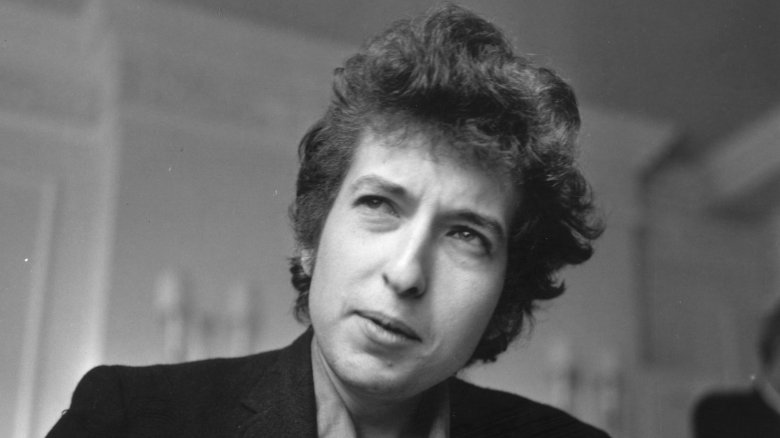

There aren't too many American musicians — or musicians from anywhere, or artists of any kind, really — that enjoy the stature of Bob Dylan. The longest-lasting graduate of the New York folk scene of the late '50s and early '60s, the former Robert Zimmerman became an icon of music, pop culture, and even letters — he's the only rock star to ever win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Since releasing his first album in 1962 at the precocious age of 20, Dylan has ranked with the Beatles, Elvis, Madonna, and the Rolling Stones as one of the foremost voices in music, shaping the sound of popular music. A great many of his songs are now classics, including "Blowin' in the Wind," "Like a Rolling Stone," "Tangled Up in Blue," and "It Ain't Me Babe." He's also the dad of that cool guy from the Wallflowers.

Dylan is as inscrutable and emotionally reclusive as he is talented and mumbly. He's a mysterious, retreating figure, but here are some confirmed stories we can report about the freewheelin' Bob Dylan.

Woodstock was so far out, Dylan got as far out as possible

Not only was the Woodstock Music and Art Fair in August 1969 the iconic cultural event of the Baby Boomer Generation (especially its "hippie" and "counterculture" contingencies), but it also marked one of the most remarkable collections of musical talent ever. Who played Max Yasgur's farm that magical weekend? The Who is who, along with Jimi Hendrix, Jefferson Airplane, Santana, the Grateful Dead ... pretty much every notable act from your dad's record collection with the notable exception of Bob Dylan.

It's not for a lack of trying on the part of Woodstock organizers. They wanted Dylan, and actually got Dylan to say he would perform. They'd started to draw up a contract and were finalizing the details when Dylan backed out just before Woodstock was scheduled to begin. And "just before" really means just before. He lived near the site where the concert was scheduled to go down, saw the hordes of hippies amassing, and canceled. (He claimed his son was sick.)

He knocked a cover of Knockin' on Heaven's Door

In the late 1980s, "it band" of the era Guns N' Roses brought Bob Dylan's music to a whole new audience with its live cover of the haunting "Knockin' On Heaven's Door." It was a big hit and a big deal for Guns N' Roses, because Axl Rose, Slash, and the boys didn't do many covers (well, before their all-covers album The Spaghetti Incident? that is), preferring to instead record their oh-so-poetic songs about paradise cities and autumnal precipitation. It took the band some persuasion to record Dylan's song, and that push came from Dylan himself.

At a 2009 concert, Rose told the crowd that before GNR recoded a studio version of the song, "Bob asked me, 'When you gonna record 'Heaven's Door'? And I said, 'I don't know, but we really love that song.' And he said, 'I don't give a f***. I just want the money.'" After Guns N' Roses did record it, Dylan said in the Telegraph that "Guns N' Roses is okay, Slash is okay, but there's something about their version of the song that reminds me of the movie Invasion of the Body Snatchers." You just can't please Bob Dylan.

He's with the band, seriously

In the weeks and months after the terrible events of 9/11, Americans were both anxious and understandably on high alert about the possibility of more attacks from out of nowhere. To that end, airports and other places greatly enhanced security measures, and in advance of a concert at the Jackson County Expo Center in Central Point, Oregon, in October 2001, Bob Dylan's director of security gave strict rules to guards hired for the event: Absolutely nobody could go back stage if they didn't have their "credential," like their ID badge on a lanyard.

So when an older gentleman with wild hair tried to breeze through a security checkpoint, some of the guards stood in his way. The man got very angry and demanded that the guards be fired. Of course, he could demand that because the disheveled man who'd tried to wander backstage ranting about firing security guards was, in fact, Bob Dylan, and he was not rocking a lanyard.

The comedy stylings of Bob Dylan

Larry Charles is responsible for a lot of great comedy — he wrote for Seinfeld and directed Borat, to cite two credits — and according to the podcast You Made it Weird (via Dangerous Minds) in the late 1990s, he teamed up with Dylan to make the singer-songwriter's old-fashioned comedy dreams come true. "He'd gotten deeply into Jerry Lewis," Charles said, "and he wanted to make a slapstick comedy. ... He wanted to star in it, almost like a Buster Keaton or something." Charles met Dylan in the back of a Santa Monica boxing gym the singer owned and sorted through a box full of pieces of paper upon which Dylan had written various phrases. "I realized that's how he writes songs. ... He has all of these ideas and then just in a subconscious or unconscious way, he lets them synthesize into a coherent thing," Charles said.

And in that manner, the two created a treatment for what Charles called "this slapstick comedy, which is filled with surrealism" and references to Dylan's songs. They pitched it to HBO — Dylan showed up to the meeting in black, head-to-toe cowboy gear — and the network put the show into production. Charles, Dylan, and their respective agents got as far as the elevator before Dylan said, "I don't want to do it anymore. It's too slapsticky."

They pitched Dylan on Catcher and he dropped the ball

According to Anthony Scaduto's Bob Dylan: An Intimate Biography (via Rolling Stone) in 1961, talent agency MCA aggressively courted Bob Dylan just before the release of his first album. MCA wasn't much interested in touting Dylan's gritty authenticity; an executive there wanted to make him a STAR, baby! "I've got two possible things for him," the executive promised. "I want him to audition for The Ed Sullivan Show, and I want to see if he can play Holden Caulfield. We own the rights to Catcher in the Rye and we think maybe we finally found Holden Caulfield."

As far as the latter goes, no movie version of The Catcher in the Rye, a classic of American literature written by the legendarily reclusive J.D. Salinger ever got made, with or without Dylan. And had he had the opportunity to star, he probably would've passed, judging by his reaction to even the notion of appearing on Ed Sullivan. According to Scaduto, he "went up to the CBS TV studios, protesting all the way" because he didn't "like to push [his] music on anyone." He played for some executives ... who "didn't know what to make of him." He never played on Sullivan's "really big show."

Bob Dylan, the Ed Wood of the '70s

The Catcher in the Rye and his ill-fated HBO comedy aside, Bob Dylan has done a fair amount of acting, albeit sporadically, throughout his career. One such resume item: the 1978 curiosity Renaldo and Clara. Dylan also directed and co-wrote the 1978 movie (with actor and Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Sam Shepard), and boy is it something.

Dylan plays Renaldo, then-wife Sara Dylan plays Clara, and other actors play "Bob Dylan" and "Sara Dylan." Joan Baez shows up as the mysterious "Woman in White," and there's a character named "The Masked Tortilla." There's also a bunch of random stuff like pinball games, New York City street preachers warning about the end of the world, a belly dancer shaking it to "Hava Nagila," and Beat poet Allen Ginsberg reading poetry. Interrupting those bits of surreality came footage from concerts on Dylan's "Rolling Thunder Tour," a period in which he appeared on stage wearing masks and white face paint. Oh, and the original cut of the thing ran four hours.

Ironically, in an interview with Playboy, Dylan said that Renaldo and Clara was "a very open movie." Film Threat disagreed, calling it "the single biggest waste of celluloid in the entire history of motion pictures" and "the very, very, very worst thing ever made." Come on, worse than Bob Dylan's Victoria's Secret commercial?

How does it feel to be kicked out of a home?

In July 2009, Long Branch, New Jersey, police officer Kristie Buble responded to a "suspicious person" report. The occupants of a home (bearing a "For Sale" sign) saw an "eccentric-looking old man" hanging around their yard before he wandered off down the street. It was a little weird, as it was raining buckets at the time, and according to Buble on Good Morning America, the man was dressed in "black sweatpants tucked into black rain boots, and two raincoats with the hood pulled down over his head." Buble asked the man why he was walking around in the rain and creeping everybody out, as he was "acting very suspicious." His response — he wanted to see the house that was for sale. Buble asked the man for his name, and, of course, he said "Bob Dylan." Buble didn't believe him, not until she put him in the back of his squad car and drove him back to his tour buses and entourage milling about outside a nearby hotel, where someone produced Dylan's passport, finally proving his identity. "It never crossed my mind that this could actually be him," the officer said. It will probably not be the last time that Bob Dylan does something so weird that the police are called.

The world didn't groove to Down in the Groove

Bob Dylan is nothing if not prolific, releasing more than 35 studio albums over his career, including unassailable classics like Highway 61 Revisited, Blonde on Blonde, and Time Out of Mind. Those and others frequently rank on "best albums of all time" lists, while his 1988 effort Down in the Groove decidedly does not. Dylan has never been afraid to try something new, such as the time he notoriously "plugged in" at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival and brought electric guitar sounds to his acoustic songs, or how Nashville Skyline is a country album. But on Down in the Groove, he maybe tried to do too much all at once.

David Fricke of Rolling Stone called the LP "confusing, frustrating, and intermittently fab" and said it "zigs and zags all over the place." It took Dylan six different recording sessions spread over six years to get all the raw material for the record, which saw its released delayed for a year and a half and its track listing repeatedly revised. Along with a lot of covers, Down in the Groove includes Dylan's not-punk song "Sally Sue Brown" despite featuring guest musicians Steve Jones of the Sex Pistols and Paul Simonon of the Clash. And then there's "Death Is Not the End," a collaboration with Brooklyn hip-hop collective Full Force.

Bob Dylan will steal your song

Joel and Ethan Coen's critically acclaimed 2013 film Inside Llewyn Davis starred Oscar Isaac as a down-on-his-luck early-1960s New York City folk musician subjected to one personal and professional indignity after another. It's loosely based on the experiences of folk scenester Dave Von Ronk, who endured some real-life unpleasantness at the hands of fellow folkie Bob Dylan.

Like a lot of folk musicians, Von Ronk's repertoire included the old standard "The House of the Rising Sun." According to the liner notes (via Esquire) of the 2013 Von Ronk compilation Down in Washington Square, he created an especially dynamic arrangement for himself, which Bob Dylan liked so much that he asked Von Ronk "if he could record it for his first album" in 1962. Von Ronk's reply: "I'd rather you not, I'm planning on recording it soon myself." The problem: Dylan had already recorded the song. Once Dylan's album came out, Von Ronk had no choice but to drop "The House of the Rising Sun" from his act, lest people think he was ripping off Dylan (who was actually ripping off him).

Who's Bob Dylan anyway?

Has any other music star expressed the inexpressible, the deep feelings of the human heart — love, despair, hopelessness, joy — more effectively than Bob Dylan? He's as authentic as they come, a straightforward troubadour and poet who writes stark, simple, honest songs. And for more than 50 years, he's done it all with a stage name, generally the provenance of pop stars and movie actors. The singer-songwriter was born Robert Allen Zimmerman in 1941, and early in his musical career adopted the name Bob Dylan, taking the Bob as a shortened form of his given name, Robert. No one is sure where the Dylan part comes from, since the singer has offered many different origin stories for it over the years. It might come from "Matt Dillon," the main character from the TV show Gunsmoke, or be a reference to the football player Bob Dillon. The most accepted story is it's an homage to the poet Dylan Thomas.

But before he decided on that particular fake name, Mr. Zimmerman toyed around with another performance moniker: Elston Gunn, under which he played piano backing up pop idol Bobby Vee. Other Dylan pseudonyms used over the years: Tedham Porterhous, Robert Milkwood Thomas, Blind Boy Grunt, Sergei Petrov, and Jack Frost. By the time he joined the supergroup the Traveling Wilburys in the '80s — where every member, including Tom Petty and George Harrison, took on stage names — the practice was old hat to Dylan, or rather Boo Wilbury.

He's the marrying (and keeping the marriage secret) kind

If Bob Dylan is as important as the Beatles, he's had a love life as complicated as that of four other rock stars put together. In 1961, Dylan met Suze Rotolo, and they broke up a few years later when Dylan's relationship with singer Joan Baez evolved from professional to personal. Soon, Dylan left Baez for Playboy bunny Sara Lownds, marrying her in 1965 when she was pregnant with their first child, Jesse. The marriage ended in divorce in 1977 when Lownds caught Dylan at the kitchen table one morning having breakfast with their kids ... and some mystery woman. Dylan remarried again in 1986, to backup singer Carolyn Dennis, with whom they had a daughter together named Desiree. The couple split up in 1990, but amazingly, the relationship remained a secret until a biographer uncovered it in 2001.

Dylan had even more secrets. In 1991, a court ordered Dylan to pay alimony to Ruth Tyrangiel, who'd proved she'd been in a romantic relationship with the singer for more than 16 years. Then in 1998, his sometimes girlfriend Susan Ross revealed that Dylan had told her he'd also once secretly married backup singer Clydie King and fathered two children with her. Bob Dylan has a lot of love to give.

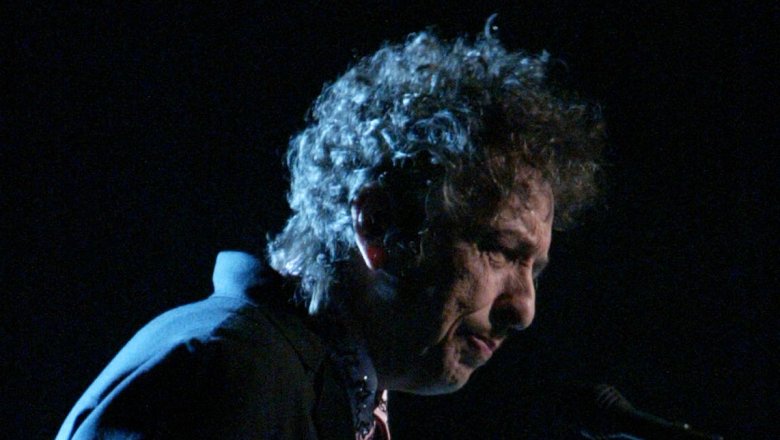

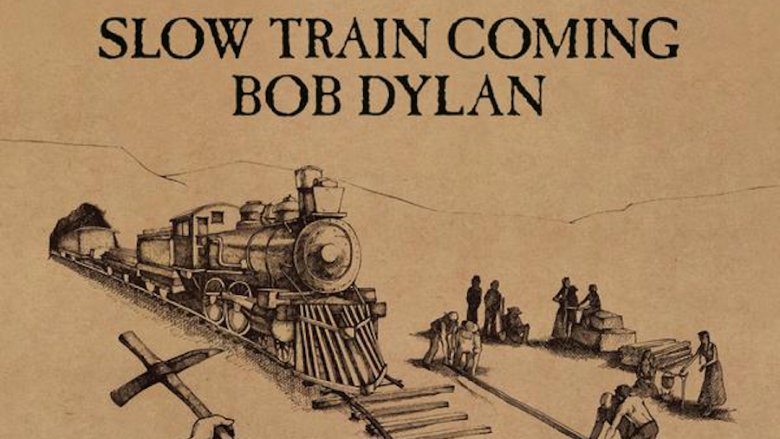

He found religion (and then lost it)

Bob Dylan became a "born-again" Christian, moving away from his Jewish background. According to a tale recounted in Ian Bell's Time Out of Mind: The Lives of Bob Dylan, the singer found himself in a Tucson, Arizona, hotel room in November 1978 and sensed "a presence in the room that couldn't have been anybody but Jesus." The presence placed a hand on Dylan, which caused his "whole body" to shake. That supernatural experience and feeling "the glory of God," Dylan says, led him to embrace Christianity not only in his heart but also in his work. Between 1979 and 1981, Dylan recorded three albums of explicitly Christian material: Slow Train Coming, Saved, and Shot of Love. The first performed the best, reaching #3 on the U.S. album chart and spawning the single "Gotta Serve Somebody," Dylan's first top 30 hit since 1973. However, when he played only religious material to the chagrin of a classics-craving crowd in Tempe, Arizona, in 1980, he told fans, "If you want rock 'n' roll, you can go see Kiss and rock 'n' roll all the way down to the pit!" Then, not long after he implied Kiss fans would permanently party with the devil, Dylan was back to Judaism in a big way, studying the faith with rabbis.