Heartbreaking Reasons These Old Hollywood Stars Were Fired

Hollywood was a secretive place in the mid-20th century. Nowadays, the entertainment news complex, the internet, paparazzi, and social media make it tough for celebrities and their handlers to control the narrative. If there's backstage drama on a movie set, the public will likely hear about it virtually as it happens. This just wasn't the case in old Hollywood. From the 1920s to the 1960s, studios tightly and fiercely controlled the dissemination of information coming out of its soundstages, backlots, dressing rooms, and offices. If a big-time movie star misbehaved during a production, or they were fired for an egregious or serious reason, the average moviegoer wasn't likely to find out about it. The news about movie star fights, breakdowns, and health issues became the stuff of rumor, gossip, and future tell-all memoirs.

But Old Hollywood was of course as scandal-prone as contemporary show business. Many of the most famous, beloved, theater-filling stars of Hollywood's golden age found themselves dismissed from major motion pictures for reasons that might anger, upset, or sadden contemporary fans. Here are some bits of showbiz lore that turned out to be true — the actors tragically and shockingly fired from movies.

Laurence Olivier wasn't good enough

Laurence Olivier is almost universally regarded as one of the finest actors of the 20th century. Rising up through the U.K. theatrical world, that country's top stage awards are named after him, and he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for his service to the arts. He'd ultimately earn 11 competitive Academy Award nominations, winning for acting in his self-directed take on William Shakespeare's "Hamlet" in 1948. But all those accolades came well into Olivier's career.

In the early 1930s, Olivier entered into screen acting, landing roles in films like "Friends and Lovers," "The Yellow Ticket," and "Queen Christina," a biopic about the 17th century Swedish monarch. Olivier was new to the movies, and his lack of a reputation preceded him. "Queen Christina" star Greta Garbo had accepted the casting of Olivier as romantic lead Don Antonio, but then she filmed a love scene with him, and she decided he needed to go.

"What happened was that I started working with Garbo and I just didn't measure up. I wasn't good enough for her," Olivier later said in a TV interview. "But she was an absolute master of her trade and she was a great figure and had an enormous image to the public." John Gilbert, Garbo's frequent co-star in her silent film era, would wind up portraying Don Antonio.

Joan Crawford was so severely teased she fell ill

"Hush... Hush, Sweet Charlotte," a 1964 Twentieth Century Fox thriller about a woman driven to insanity by family secrets, was supposed to feature Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. They'd previously co-starred in the similarly campy 1962 horror movie "What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?" Just as their characters in that film were violent rivals, Davis and Crawford felt a similar animosity toward one another. During production of "Hush... Hush, Sweet Charlotte," Davis frequently and loudly complained about Crawford, to her face and to the crew. For example, Davis criticized Crawford's character work in the middle of a rehearsal with director Bob Aldrich; Crawford stayed in her dressing room as much as possible. She internalized the stress to the point where she became physically ill and stepped away from filming when she checked into Cedars of Lebanon Hospital in Los Angeles with a fever and a cough.

Production continued on "Hush... Hush, Sweet Charlotte" as best as it could without one of its stars. Fox stood to lose $50,000 each day Crawford's hospitalization led to delays, and the film's insurer issued an ultimatum to the moviemakers — get a new actor to take over for Crawford, or scrap the movie. The former became the solution, with Olivia de Havilland hired at Davis' urging. Crawford learned she'd been fired when Hollywood gossip columnist Dorothy Manners telephoned her in her hospital room and asked how it felt to be fired and replaced.

Clara Bow asked to be fired after a horrendous trial

The popular and enduring image of a young, independent American woman in the Jazz Age of the 1920s, commonly known as a "flapper," is thanks in large part to Clara Bow. Known as Hollywood's "It Girl" at the time, the trendsetting actor and sex symbol was a box office pull in the early and silent film industry, starring in dozens of movies including "True to the Navy," "Her Wedding Night," "Love Among the Millionaires," and "Wings," the first winner of the Academy Award for Best Picture.

In 1930, Bow ceded control of her extensive fortune to Daisy DeVoe, her secretary, an arrangement that lasted less than a year. Bow fired DeVoe, who responded by stealing $20,000, financial paperwork, letters, and jewelry from the actor and then announced plans to sue for unpaid salary. That suit didn't happen, but a dramatic trial did, after DeVoe was indicted on 37 charges of grand theft. Bow's spending habits came to light during the proceedings, as did excerpts of the very personal letters stolen by DeVoe, as they entered into the record as evidence. Deeply embarrassed by the ordeal, Bow checked into the Glendale Sanatorium, a mental hospital, in May 1931. At her request, and publicly framed as a mutual decision, Paramount fired Bow from her next film, "City Streets." Bow retired from filmmaking and went to live on the Nevada ranch of her husband, actor Rex Bell.

Vivien Leigh's bipolar diagnosis precluded her from working

British actor Vivien Leigh reportedly beat out more than 200 women to play Scarlett O'Hara in the 1939 film adaptation of Margaret Mitchell's bestselling, Pulitzer Prize-winning Civil War epic "Gone With the Wind." She'd win an Academy Award for Best Actress, and another for portraying Blanche DuBois in 1951's "A Streetcar Named Desire." Within a year after taking home her second Oscar, Leigh's career was in jeopardy because of difficult-to-manage health problems.

According to The Hollywood Reporter, Leigh began to demonstrate symptoms of bipolar disorder, or manic depression (via Healthline), in the late 1930s, at one point enduring episodes of behavioral extremism on the set of "Gone With the Wind." With no effective medication yet available to balance her moods, Leigh was subject to moments of mania and sadness alike. Her behavior was so sad and unnerving to "Elephant Walk" producers that they summoned her husband, Laurence Olivier, to the film's Sri Lanka set. He wasn't able to help, and shortly thereafter filming moved to Los Angeles. Mental health episodes continued to befall Leigh, where she suffered from bouts of extreme depression and leveled profanity-laced verbal attacks at others on set. Producers again sought outside help from actor associates; David Niven held Leigh down while a nurse delivered an intravenous dose of sedatives. After that, Leigh was fired and returned to her home in London, and Elizabeth Taylor ultimately starred in "Elephant Walk."

George C. Scott showed up late

After dozens of roles in mostly individual episodes of television series and anthologies, George C. Scott seemed poised to solidify his substantial jump from small-screen character actor to big-screen leading man in the mid-1960s. After breaking through as unhinged General Buck Turgidson in Stanley Kubrick's multiple-Oscar-nominated Cold War satirical comedy "Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb," Scott was all set to star with Audrey Hepburn in the 1966 heist comedy "How to Steal a Million."

That movie's director, William Wyler, was among the most esteemed and powerful filmmakers in Hollywood, a three-time Academy Award winner for Best Director against 12 total nominations. Wyler very much valued punctuality on his projects. "The very first day of filming, Scott was an hour late to the set," Wyler told producer Lawrence Turman, according to the latter's memoir, "So You Want to Be a Producer." "I fired him immediately. The studio went crazy. They begged me to reconsider. But I stood firm."

Spencer Tracy got drunk and pushy

Fox Film Corporation produced the 1935 horror movie "Dante's Inferno," inspired by the 14th-century narrative poem "The Divine Comedy." Starring as morally flexible fairground operator Jim Carter: contract player Spencer Tracy, appearing in his 25th film for Fox since 1930. A few years before his back-to-back Academy Award for Best Actor wins for "Captains Courageous" and "Boys Town," Tracy didn't yet have a lot of movie business clout, but he still tried to affect change on the set of "Dante's Inferno," insisting that filmmakers rewrite the script to his liking. At one point, Tracy started a physical fight with director Harry Lachman and in an emotional tirade, reportedly destroyed whatever props, scenery, and lights were in the immediate vicinity before security guards could subdue him. During that particular incident, Tracy had shown up to work extremely drunk.

Following the completion of filming, Fox executives met with Tracy and warned him to behave properly on his next movie. The actor immediately found a bar, and after drinking for four hours, returned to the Fox offices and confronted his bosses. They ended his contract immediately.

Robert Mitchum got in a fight

In films like "Cape Fear," "The Night of the Hunter," and "Out of the Past," tough-guy actor Robert Mitchum often played intimidating and unapproachable figures. He was all set to star in 1955's "Blood Alley" as an American merchant ship captain who helps Chinese peasants abscond to Hong Kong. He didn't last long on the movie. "Robert Mitchum has been fired after delaying production and refusing to apologize for creating disagreements among the production staff," a press release distributed by Warner Bros. said at the time (via "Robert Mitchum: 'Baby I Don't Care,'" by Lee Server).

Movie reporters descended on the "Blood Alley" set in San Rafael, California, where one overheard a crew member comment that Mitchum had been under the influence of drugs. "Always walking about six inches off the ground. He punched a guy, one of the drivers, knocked him into the bay, d*** near killed him." In the wake of the firing and the speculation, Mitchum told his side of the story in a press conference held in his motel room. "It was all a result of my championing of the little guy," Mitchum said, dressed in his underwear and drinking wine from the bottle. "I want them treated right." Mitchum had evidently advocated for some crew workers who weren't being given necessary hygiene products by Warner Bros., and in his telling, a confrontation over that issue had turned violent. Starring in "Blood Alley" instead: John Wayne.

Clint Eastwood's appearance offended executives

For better or for worse, becoming a movie star is as much about appearance as it is about sheer acting talent or quality of performance. Conventionally attractive actors are often elevated to the A-list by movie studios, filmmakers, and receptive audiences because they possess a hard-to-define star quality, in that they just look like a movie star ought to look. Clint Eastwood, a bankable actor and major movie star from the 1960s onward, got his start as a Hollywood bit player in the 1950s, and his career almost ended before it really took off because some executives thought he lacked the necessary physical attributes required for film stardom.

In 1959, Universal Studios ended its contractual agreement with Eastwood and his friend, fellow aspiring actor Burt Reynolds. "He was fired because his Adam's apple stuck out too far. He talked too slow," Reynolds told CNN's "Larry King Live" in 2000. "And he had a chipped tooth and he wouldn't get it fixed."

Judy Garland wasn't healthy enough to act

For the better part of a decade, Judy Garland was MGM's go-to performer for grand movie musicals. A captivating actor and extremely skilled singer, Garland starred in multiple classic song-and-dance pictures, including "The Wizard of Oz" in 1939 and "Meet Me in St. Louis" in 1944. When MGM, Garland's contracted studio for a decade and a half, entered production on the 1948 musical "The Pirate," Garland was cast in the lead role of Manuela. During filming, Garland, who had long dealt with drug addiction, fully relapsed, relying on a variety of medications to both sleep and to stay awake. That exacerbated Garland's mental health issues; the actor would neglect to report for work, or would refuse to leave her dressing room if she did. After filming, she checked into a mental health facility and upon returning to Hollywood, began work on the musical "Annie Get Your Gun," Garland was cast in the title role, Wild West sharpshooter Annie Oakley.

Her hospitalization hadn't brought Garland back up to her peak, in the view of MGM executives. After one month of shooting, the studio dismissed Garland and brought in Betty Hutton. The reason: She showed up late to the set too many times and sometimes intoxicated, appeared to have gained weight, and seemed generally too worn out and unreliable.

Ray Milland refused a role

Signed to a seven-year contract in 1934, Ray Milland became a versatile leading actor for Paramount Pictures, almost always starring in movies marketed as lightweight, like comedies, Westerns, and adventures. It was something of a surprise to even Milland himself when Paramount cast the actor in "The Lost Weekend," a dark and difficult drama about an alcoholic writer who engages in a four-day binge-drinking session. "I wasn't at all sure I was ready for it," Milland said of the movie before filming began (via the Los Angeles Times). He lost weight for the role, got drunk in public for real, and spent the night in a New York hospital's section for unhoused alcoholics.

Milland was well-rewarded for his role with an Academy Award for Best Actor in 1946. He thought he'd transformed his career and graduated to more serious fare, but his bosses at Paramount Pictures didn't necessarily agree. In 1948, the studio ordered him to star in a thriller called "Bride of Vengeance." Milland refused to show up to the set, telling Paramount that he thought the role was beneath him, and that the resulting film wouldn't be very good. Paramount placed the actor on a two-month suspension and in "Bride of Vengeance," replaced Milland with actor John Lund.

Marilyn Monroe didn't show up too many times

Marilyn Monroe became a legend in the 1950s with roles as an object of desire in comedies like "Gentlemen Prefer Blondes," "How to Marry a Millionaire," and "Some Like It Hot." In 1962, she started work on Twentieth Century Fox's "Something's Got to Give." Monroe was coming off of a year-long hiatus spent recovering from gallbladder removal and endometriosis surgeries, fighting drug addiction, and a hospitalization for depression. On the set of "Something's Got to Give," Monroe had trouble recalling her dialogue, and crew members noted that she seemed to be both heavily drugged and deeply despondent. But that's if Monroe was around at all; she called in sick more than she showed up, her absences explained by notes from her doctors.

In May 1962, after failing to report to the set for several days over illness, Monroe sang a sexy version of "Happy Birthday" to President John F. Kennedy (with whom she'd possibly enjoyed a dalliance) at an event in New York. "Something's Got to Give" director George Cukor, who'd given Monroe the go-ahead to attend weeks earlier, got so angry that he had Fox fire the actor for her frequent absences. The studio then hit her with a $750,000 breach of contract lawsuit.

Months later, Fox brought back Monroe after co-star Dean Martin refused to work with replacement Lee Remick. But before filming resumed, Monroe was found at her home, dead at age 36 from a fatal and likely intentional drug overdose.

Loretta Young tried to defy the studio system

It would have been extraordinarily scandalous, and potentially career-ending, for an unwed A-list Hollywood actor in the 1930s to give birth to a child. According to a BuzzFeed News interview with Loretta Young's daughter-in-law, in 1935, the actress became pregnant via a sexual assault by mega-star Clark Gable, her "Call of the Wild" costar. Fox demanded that Young clandestinely abort the pregnancy. As a Roman Catholic, and opposed to birth control and abortion, Young refused. So the studio, to which she was a contracted actor, concocted a story in which Young was reportedly convalescing from an unnamed illness in Europe. Young then quietly returned home to Los Angeles and gave birth to a baby girl, whom she then publicly adopted 19 months later.

Her career back on track by 1939 with the ruse a success, Young would once more refuse to do what her studio wanted, and her career suffered. Fox offered her a five-year contract worth $2 million, and Young declined to sign. Attempting to go around the contract system, Young aimed to sign deals with individual studios. It didn't work. Unwelcome at most every studio in Hollywood, not just Fox, for challenging the way they did business, Young could only secure a role in one movie between 1939 and 1941, "Eternally Yours," for United Artists.

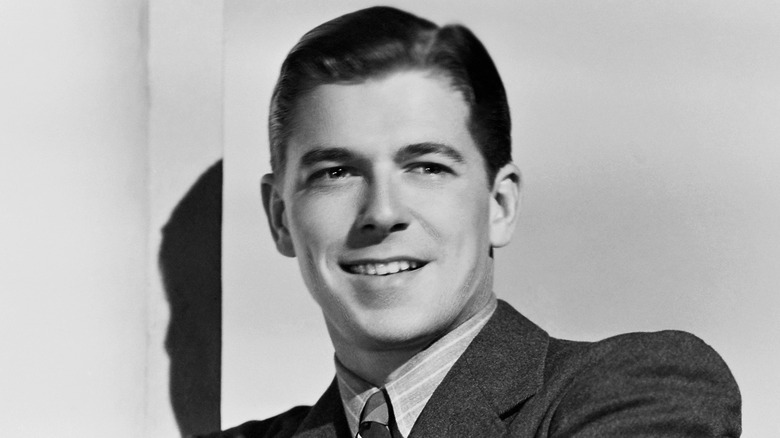

Ronald Reagan trashed his studio

In the 1930s and 1940s, Ronald Reagan was a contract player with Warner Bros. Never a major box office draw or a particularly acclaimed actor, Reagan mostly headlined second-rate B-movies like "The Voice of the Turtle," "Stallion Road," and "Santa Fe Trail."

By 1950, Reagan had grown tired of unchallenging work, and he said as much to reporter Bob Thomas. He'd been forced to sit out moviemaking for most of 1949 after hurting his leg, and he planned on turning over a new leaf in his work. "After spending most of the last year in bed, I'm going to concentrate on my career in 1950," Reagan told Thomas at the time (via GoUpState). "And there'll be some changes made... I'm going to pick my own pictures. I have come to the conclusion that I can do as good a job of picking as the studio has done."

That interview was quickly published, and it crossed the desk of Jack Warner, head of Warner Bros., Reagan's employer. Livid that Reagan would criticize his studio's films, he wrote to Reagan's agent, Lew Wasserman, to confirm the veracity of the interview. It was all true, and so later that year, when Reagan's contract came up for renewal, Warner purposely declined to re-sign. Reagan departed for Universal, at the time seen as a second-tier studio, where he made the comedy "Bedtime for Bonzo," starring opposite a chimpanzee.

Gene Kelly got angry and hurt himself

Gene Kelly ruled the world of big-budget movie musicals in the 1940s and 1950s. Not only did he star in and hoof his way through the likes of "Anchors Aweigh," "An American in Paris," and "Singin' in the Rain," but he also devised and choreographed those films' elaborate dance numbers.

When expert dancing was a major element of big-screen entertainments in the mid-20th century, Kelly's only real rival was Fred Astaire, and in 1947, he lost a role to Hollywood's other big male dancer-actor-singer due to an injury of his own creation. Filming was set to begin on "Easter Parade" in October 1947, and Kelly intended to spend two months preparing and choreographing the movie's dance sequences. On the day that screenwriter Sidney Sheldon turned in the final script to filmmakers, he was informed that Kelly had broken his leg. Kelly told MGM studio executives that he'd hurt himself practicing his dance moves. That was a lie to save face. He'd actually suffered a broken ankle during a volleyball game with friends. With every point his team ceded to the opposition, Kelly got angrier, eventually kicking a nearby doorframe so hard that he busted a bone. Kelly asked MGM to get rid of him and to bring in Astaire.

Buster Keaton didn't work well with his studio

Known as "the great stone face" for his stoic reaction shots to the zaniness that surrounded his characters, Buster Keaton was among the most popular figures of silent film. Following hits like "The General" and "Steamboat Bill, Jr.," Keaton's star had dimmed somewhat as movies with sound took hold, and in 1928 he signed an exclusive contract with studio MGM. Executive Irving Thalberg assigned a studio employee to oversee Keaton's films as well as devoting a whole team of writers and other crew members to the comedian's projects. MGM churned out movies in this efficient, stratified system, and Keaton wasn't used to that, as in the past he'd been granted full creative control and hiring authority.

Over the span of four years of working in the MGM manner, Keaton grew increasingly unhappy and felt creatively stifled. He coped with his discontent by drinking heavily, particularly on set. In 1932, MGM executive and co-founder Louis B. Mayer invited himself to a particularly intense and alcohol-fueled party over which Keaton presided in his own dressing room. Resenting Mayer, and viewing the unwelcome presence of the executive (as well as a bunch of Mayer's friends and their dates) as another instance of studio interference, Keaton erupted and threw his boss and his associates out of the party. Days later, Keaton refused to attend an important MGM public relations event. Two days after that, MGM fired Keaton and began aggressively pursuing the Marx Brothers to be its new marquee comedians.

Lita Grey got pregnant with the director's baby

An icon of silent cinema, Charlie Chaplin wrote and directed many of his movies, including the 1925 adventure comedy "The Gold Rush." He also starred as the Lone Prospector, a riff on his popular, downtrodden Tramp character. Chaplin handed the only significant female role in "The Gold Rush" to Lita Grey (real name Lillita MacMurray), who at that time had appeared in just two films, "The Idle Class" and "The Kid." They were both Chaplin movies, and Grey had been around 12 years old when they were produced. She was 15 when Chaplin signed her to a contract, placed her in "The Gold Rush," and began a relationship with her.

Six months after filming began, Grey became pregnant with Chaplin's child. To avoid statutory rape charges, Chaplin married Grey in a secret ceremony in Mexico. Chaplin's publicity agent, Jim Tully, told reporters that Grey had quit not only "The Gold Rush" but acting altogether, desiring to spend her days doting on her new husband. The world wasn't yet aware that Grey was pregnant, or had gotten pregnant out of wedlock. Because she'd show the physical effects as filming continued, Chaplin had actually fired his teenage wife from "The Gold Rush" and then replaced her in the movie with actor Georgia Hale.

If you or anyone you know needs help with mental health or addiction issues, is in crisis, or has been a victim of sexual assault, contact the relevant resources below:

- The Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

- The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

- Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org

- The Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).