What It Was Like Being A Burlesque Dancer In 1920s America

At the beginning of the 20th century, most Americans kept things pretty buttoned up, figuratively and literally. Sure, some took in a vaudeville show, and perhaps one of those acts would involve early burlesque dancers showing off their calves, but the skirt-lifting tended to stop there — and dancers' legs were usually covered with stockings to boot. It may have been shocking to at least some folks at this time, but burlesque dancers in just a short time would be doing far more than lifting their dress a bit and telling cheeky jokes. By the 1920s, some would even be getting very close indeed to the audience while wearing almost nothing at all.

These eye-widening changes in burlesque dancing reflected many wider changes in American society and morality, with some people really loosening up and others engaging in reactionary shock and disgust. Consumption was changing, too. With rising economic fortunes, many Americans engaged more with emerging media like film and jazz music. Some women also pushed social boundaries, wearing more revealing clothing, going out to nightclubs, indulging in alcohol (despite Prohibition), and more. While few were the full-on flappers of conservative nightmares, there was one particular subset of women who made 1920s moralists tut-tut: the burlesque dancers.

But dancers' lives would have forced them to navigate hooting audiences, legal challenges, and, sometimes, the travails of life on the road — all putting them at the center of cultural and ethical debate.

Prohibition gave burlesque dancers a boost

Being a burlesque dancer was never going to be the prestigious arts career that some people aspired to. That was made all the more obvious in the 1920s with the rise of Prohibition. Starting in 1920 and continuing until 1933, the 18th Amendment forbade the creation and consumption of alcohol in the United States, while the Volstead Act (which debuted in 1919) defined an alcoholic drink as anything containing more than 0.5% alcohol by volume. However, those who loved a good time circumvented the federal law, patronizing underground drinking establishments known as speakeasies (which were often connected to organized crime outfits willing to exploit the illegal bars). Some of these quasi-secretive clubs also put on shows for patrons, giving burlesque an alcohol-infused boost. Burlesque and Prohibition also grew to be partners once upper-class folks began making their way into less prestigious neighborhoods, patronizing underground bars and taking in shows that weren't all that concerned about engaging with high society.

Other business owners, like theater proprietors who faced a downturn in profits once they were forbidden from selling alcohol, turned to titillating burlesque shows to bring audiences back. Even seemingly legitimate theaters on Broadway felt the push to dress dancers in less and less clothing, influenced by both burlesque and European revues that carried less puritanical notions about nudity (or near-nudity, anyway). What's more, many non-dancers outside of the shows were increasingly willing to push the envelope, with hemlines rising, necklines dipping, and morals loosening.

Burlesque dancers often worked alongside other performers

For much of the 1920s, burlesque dancers weren't guaranteed to be the stars of the show. Given that burlesque dancing has its roots in the vaudeville circuit, early 20th-century dancers were more likely to be part of an ensemble that presented a variety of acts, including comedians and musicians.

Depending on where you were taking in a burlesque show in the 1920s, dancers might have been billed well below comedians, once considered to be the big stars of a burlesque show. Back in the day, quite a few big-name stars of film and television got their start making jokes on the burlesque circuit, including the duo of Abbott and Costello. Lou Costello — who became a burlesque comedian after a stunt injury temporarily pushed him out of 1920s Hollywood — was so entrenched in that world that he romantically pursued one of the burlesque dancers in a show where he was a resident comedian. The woman in question, Anne Battler, was skeptical of starting a relationship with the young comic, however. Despite her initial hesitation, the two married in 1934 and remained together until Costello died in 1959.

Burlesque dancers might also be accompanied by singers, who earned raunchy nicknames for their work accompanying the increasingly unclad dancers on stage. One of those singers was Robert Alda, whose son, Alan Alda, would become a film and television actor on shows like the ever-popular "M.A.S.H."

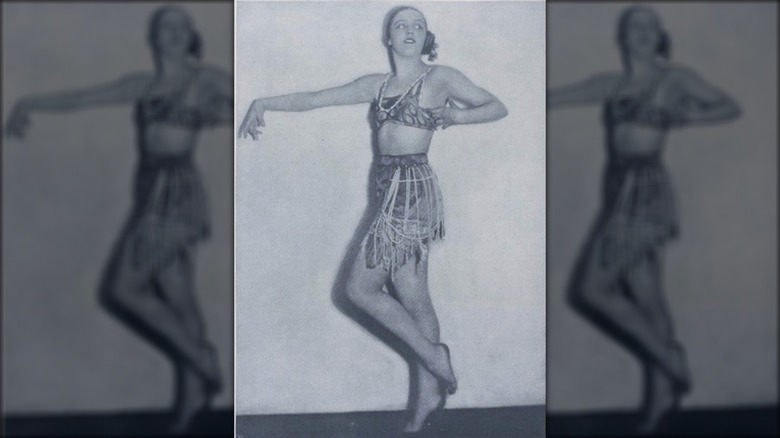

Striptease was often part of burlesque acts

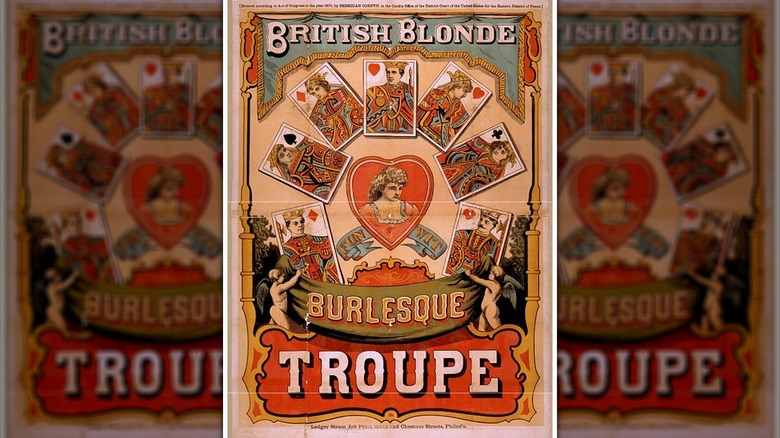

In the U.S., most sources trace the modern pedigree of burlesque dancing back to the 1868 New York City debut of Lydia Thompson's British Blondes, a troupe of dancers whose satirical comedy may not have drawn interest so much as their then-racy display of legs clad in tights. However, the women in Thompson's traveling show did not strip while on stage. By the 1920s, however, that was a very different story.

According to some accounts, the first striptease in burlesque was an accident, though who started it and exactly what they did is hard to pin down. Some claim it happened in 1904 when Millie DeLeon removed a garter, while others credit a 1917 dancer who started pulling off her costume before she was out of sight of the audience. Yet other tales say the first strip show happened in 1917 courtesy of Mae Dix, who simply removed a soiled cuff — or wait, was it a strap that broke?

While the inventor of the burlesque striptease is up for debate, what's abundantly clear is that, by the 1920s, burlesque dancers were showing some serious skin. For instance, by the end of 1923, Carrie Finnell was titillating Midwestern audiences by removing bits of her costume. She claimed to have worn bottoms that were held together by a series of straps. Her innovation: removing a strap each week. As she later told reporters, the extended tease took 10 weeks to complete.

For many dancers, burlesque was a way to earn money

Though surely many dancers came to the world of burlesque with stars in their eyes, for many it was simply a job. As author and filmmaker Leslie Zemeckis told TIME when discussing the history of burlesque dancers, "I don't think they felt empowered. They were working and doing a job ... They had no choice, a lot of them, coming from hard economic times and abusive situations."

Economic hard times were, for at least some, an undeniable fact of life in the 1920s. Though the stock market crash that kicked off the Great Depression didn't happen until 1929, it was preceded by years of ballooning economic conditions that may have seemed great on the surface but were accompanied by uncertain futures, rising unemployment, growing debt, and stagnating wages. While some people were investing heavily in the stock market, others had bills to pay. Few burlesque dancers likely came from upper-class families where money was no worry.

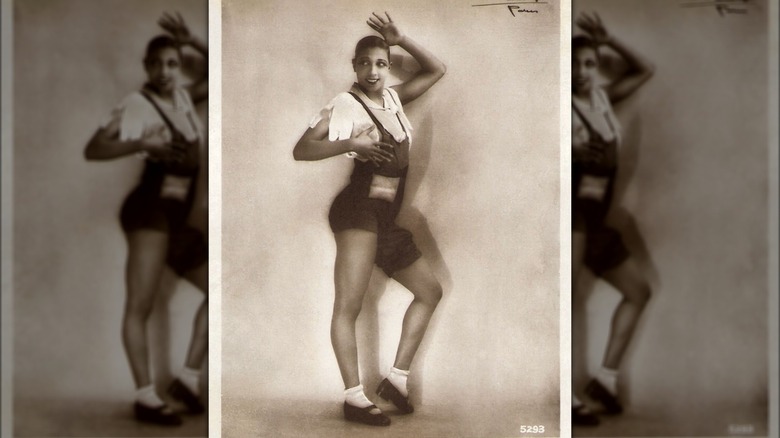

Take Josephine Baker, who rose to fame after dancing in vaudeville shows in France, and who certainly started in impoverished conditions. Born in 1906 in St. Louis, Missouri, Baker's mother withdrew 8-year-old Josephine from school to work. She eventually became a teenage dancer and, by 1919, had moved to New York City and begun a career on Broadway. It's possible that her hard work, charisma, and spendy tastes were all informed by her early poverty and the burlesque-style dancing she did to get started.

A few dancers went beyond burlesque

Some burlesque (or at least burlesque-adjacent) performers of the 1920s were able to transcend initial anonymity as one of many dancers and become famous in their own right. Josephine Baker's career began as a teenage dancer who began to draw attention in the 1920s. In 1925, she moved to Paris and appeared clad in only a feathered skirt at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, where she quickly became a hit. Later, she became a member of the French Resistance and a spy working against the Nazis, then a civil rights activist. In 1973, she was even working on a return to the stage, which abruptly ended with her sudden death in 1975.

But things weren't always easy. Baker experienced serious financial troubles in later life, to the point where her French home was seized as her debts mounted. Louise Brooks, who went from a talented dancer performing with a troupe on a European tour to a silent film star, likewise claimed to experience a career decline after she refused to accept the sexual advances of Hollywood bigwigs. Other sources claim that the real issue was her refusal to record audio for film. Eventually, she took up work as a salesperson in a New York City department store and lost friends who looked down on her new job. Later, she worked as a film journalist and published her frank, oftentimes feminist, and sometimes acid-tongued writings in her 1982 book, "Lulu in Hollywood," before she died in 1985.

Travel was often part of the business

For part of the 1920s, the reality of being a burlesque dancer meant continually packing and unpacking your suitcase, as success meant traveling from theater to theater and city to city. Even before the 1920s, the world of the burlesque circuits, also informally known as wheels, was full of competition. One of the most powerful was the Columbia Wheel, which boasted about $20 million in value and 38 stops in 1923. Initially, Columbia's claim to fame was that it presented relatively clean, family friendly fare. In that vein, Gus Hill, the producer who maintained that he originated the Columbia Wheel, tended to rely on a variety of acts and less so on the titillating spectacle of attractive dancers with scanty costumes.

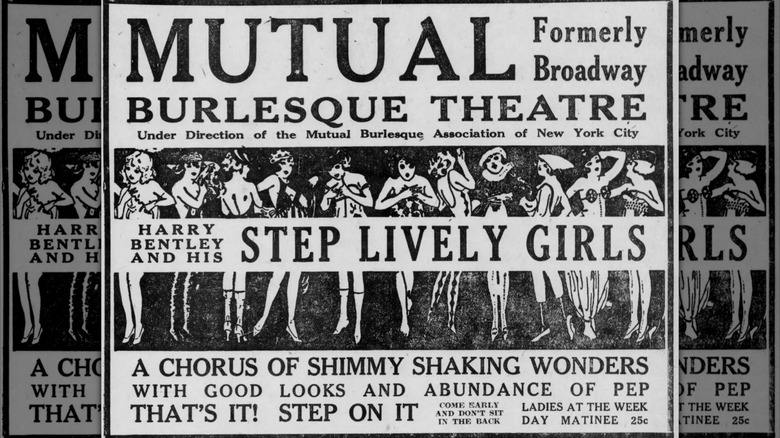

However, declining numbers made that more conventionally upstanding reputation difficult to uphold. By 1925, Columbia burlesque dancers had largely lost their tights and, for some of them at least, their tops as well. That didn't help things much, however, as Columbia merged with rival circuit Mutual in 1927. Together, the two became known as the United Burlesque Circuit. Despite the name change, dancers had to deal with an increasingly tawdry reputation and what must have often felt like an endless grind of travel and dancing before rowdy audiences. Incomes were down, too, as more and more stops closed. By 1931, the last burlesque circuit was done for, and its remaining shows were relegated to stationary theaters that hosted recurring stock shows.

Dancing sometimes meant getting uncomfortably close to the audience

If a burlesque dancer was sometimes uncomfortable with an audience's reaction to her work, she at least had the comfort of performing on a stage that was largely removed from prying eyes and grabbing hands. As the 1920s moved forward, however, that was set to change dramatically. Dancers were about to step foot onto the runway.

The runway stage, which allowed audience members to get an even closer view of burlesque dancers, was reportedly introduced to the U.S. by the Minsky brothers, who rose to prominence for their stock theater burlesque shows held in New York City spots like the Little Apollo Theater and the National Winter Garden. Allegedly, Abe Minsky watched French dancers walk a runway at the Folies Bergéres and was so taken with the sight that he decided to import it to his family's burlesque theaters in America. Once the runway stage became popular in the U.S., the largely male audience raised quite an appreciative ruckus when they realized they could get an up-close view of dancers' legs.

The runway trend quickly spread to other theaters, where dancers were soon performing up close and without tights in what was then a racy new step. Audience members reported being able to smell the perfume of dancers and hear their breathing, illustrating just how much more intimate the runway had made burlesque shows as the stage acts moved into the 1930s.

Black performers had to make complicated choices

For many dancers, there was no escaping the racism of 1920s America. In the world of burlesque dancing, the highly sexualized stage acts were sometimes linked to misconceptions about Black American culture. Yet, while some white performers were winkingly referring to these stereotypes, Black dancers were often relegated to segregated theaters and shows. It wasn't until the Great Depression that cash-strapped theater owners (some of whom had bought out establishments from Black owners) began to hire women of color.

Before then, most dancers would have performed in segregated spaces or as separate parts of "Black and White" acts, which rose in popularity if not equality during the 1920s. Burlesque-style dance acts also took place in quasi-integrated spaces known as black and tan clubs. Encouraged by changing social mores and the unsanctioned nightlife of the Prohibition era, white and Black patrons would dance, drink, and take in a show at these clubs, which also often featured a mixed group of performers — though few would take these somewhat progressive attitudes into their everyday life and others saw the black and tan clubs as symbols of a downfallen society.

Some dancers simply left town, as when Josephine Baker joined an all-Black dance company, La Revue Négre, on its way to Europe. Arriving in Paris in 1925, she went on to find great success in the French capital with her scantily clad danse sauvage number — perhaps more than she would have found back home.

Stock burlesque theaters began to take over

With the demise of the traveling burlesque circuit in the 1920s, burlesque dancers took up residence in theaters. Known as stock burlesque, these shows happened in a set theater, though dancers and other acts tended to rotate over a period of time. By the early 1920s, stock burlesque, like that run by the increasingly successful Minsky brothers in New York City, was so popular that traveling circuit shows began to shut down. Some, like the Columbia Wheel, attempted to survive by promoting its performances as relatively family friendly, but the draw of stock burlesque's more raunchy jokes and increasingly scantily clad dancers proved too intriguing to audiences, and so stock burlesque proved victorious.

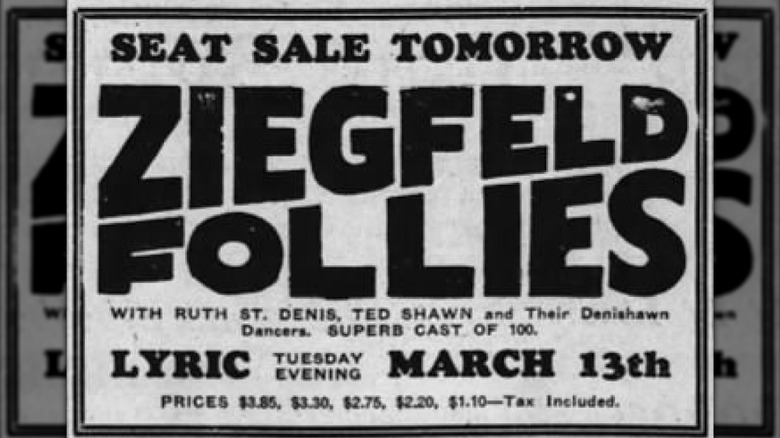

Being a stock burlesque dancer meant accepting, at least to some degree, the more down-market reputation of theater shows and the annoyances of cost-cutting theater owners. Those two factors were often related, as other dance companies like the famous Ziegfeld Follies worked to attract audiences by putting on a glitzy spectacle while struggling circuit shows still tended to monopolize the nicer theaters. Relegated to less classy digs — and arguably less classy spectators — stock burlesque established itself as the shows that were willing to go there. As the ones with the flesh on display, burlesque dancers were at the forefront of this change, though most seem to have been pushed to do so by managers and proprietors rather than making the choice fully on their own.

Dancers faced moralistic backlash

Burlesque was hardly highbrow entertainment in the 1920s. Neither was it accepted by everyone who came across the spectacle of barely dressed women dancing before a lascivious audience. Some of those offended onlookers included John Sumner, who in 1925 was the secretary for the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. Sumner had apparently witnessed a nude burlesque act performed by dancer Mary Dawson at one of the Minsky brothers' theaters. He made a formal complaint, police raided the premises, and nine people (including Billy Minsky) were charged with producing a performance that corrupted morals. However, though this was just one in several attempts to pump the brakes on ever more scandalous burlesque, dancers kept putting on their acts well into the 1920s and beyond.

Still, some caution was required. In the Minskys' theaters, dancers were allegedly warned of vice squad activity via a special light. If the stage manager caught sight of a police officer on the premises, they would be able to flip on a red backstage light, alerting performers that it was time to switch to a cleaner dance routine.

Of course, burlesque dancers were not necessarily wracked with guilt over their work or its moral implications. As Josephine Baker once claimed, "We hide the buttocks too much. They exist. I don't see what reproach should be offered them" (via "Josephine: The Hungry Heart"). Despite the pearl-clutching going on, at least some of the burlesque dancers were just fine with their work.