Hitler's Lies That People Actually Believed

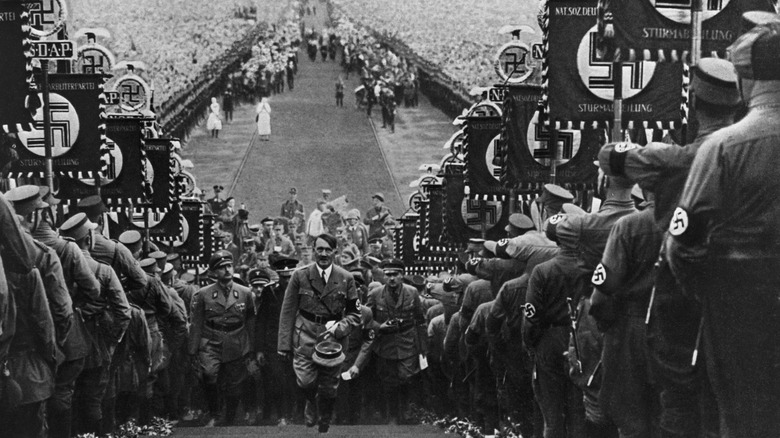

According to University of Cambridge historian Piers Brendon, the 1930s were the decade that solidified the tendency of big people to tell big lies. In a piece for The Guardian, Brendon wrote that lies were now being told on a grand scale — undoubtedly spread via new technologies — from the misinformation surrounding the Great Depression to the falsehoods and myth-making that allowed Adolf Hitler to seize power during the struggles of a post-World War I world.

In hindsight, it's easy to look back and wonder how the world allowed things to get so far before someone stepped up to stop Hitler's mad scramble for power. But Brendon stresses that at the time, it was the perfect storm for someone like him to rise to the top of the political food chain. Germany was fresh out of a crushing World War I defeat, and people wanted answers. Why had Germany lost? What had gone wrong? Who was to blame? Hitler gave them answers... and it didn't matter whether or not they were truthful. They were answers that offered justification, comfort, and — most importantly — a way forward.

Brendon also quotes the German existentialist philosopher Martin Heidegger, who said, "The Fuhrer himself, and he alone, is Germany's reality." It doesn't need to be said just how dangerous an idea that is, but especially in today's era of fake news that can spread faster than the actual wildfires, it's important to remember just what Hitler had to say, how far from the truth it actually was, and the consequences that came from unquestioning belief and acceptance.

He started with claims he only wanted to restore the German state

Post-World War I history is complicated, but in a nutshell, the Treaty of Versailles imposed steep penalties on the losing countries, including Germany. And that's what Adolf Hitler seized upon: He made promises that he only wanted to restore Germany to its pre-war glory in terms of both prosperity and territory, and for a long time, other countries were happy to take him at his word. Tim Bouverie is the author of "Appeasement: Chamberlain, Hitler, Churchill, and the Road to War," and as he explained to Time, Hitler's repeated claims were convincing enough that European leaders held off on declaring outright war. Except...

"Both of these claims are proven as lies when he invades Czechoslovakia in March 1939 and the British government realizes that he is intent upon wider European conquest — possibly domination," Bouverie says.

Hitler's lies had been so convincing that Europe's foremost powers had signed the Munich Agreement in September 1938, which gave Hitler's Germany a portion of Czechoslovakia — the Sudetenland, which was home to about 3 million ethnic Germans. Great Britain, Italy, and France signed with Hitler's promise that he wasn't going to go any further... and everyone knows how that worked out. Interestingly, even as Britain called out Hitler for violating the agreement and marching into Czechoslovakia, France still urged caution and appeasement instead of war. Britain, however, was starting to make its position clear: Appeasement had not worked, and Hitler could not be trusted.

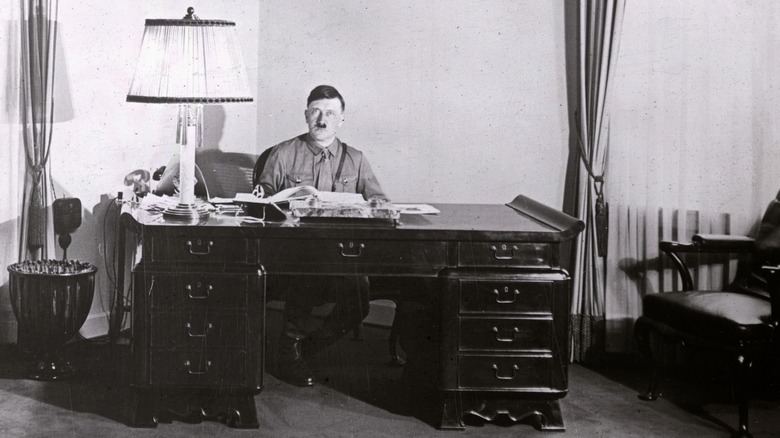

The Hitler biography... that he wrote himself

Did people really believe that the 1923 book "Adolf Hitler: His Life and His Speeches," which painted its subject as Germany's savior, was authored by a conservative German aristocrat and war hero named Victor von Koerber? Absolutely; it wasn't until 2016 that Thomas Weber, a historian from the University of Aberdeen, discovered that instead of being a glowing recommendation from an upstanding German elite, it was written by Hitler himself.

Hitler's lie about the authorship of the book turned it into a crucial bit of propaganda that essentially allowed him to tell another lie by implication: that he had the support of Germany's conservative establishment, when he definitely did not. The book wasn't subtle, either — it compared Hitler's move into politics to the resurrection of Jesus Christ. The author even suggests the book should be read as "the new bible of today." It wasn't until Weber got a look at von Koeber's private papers that he found documents indicating that he'd just been a front to lend weight to the idea that Hitler was Germany's savior-in-the-making.

Weber says (via the BBC) that writing the book not as an autobiography but in a way that seemingly gave him an endorsement by a well-known and well-respected figure was impressively deliberate: "To find that it was actually written by Hitler himself demonstrates that he was a conniving political operator with a masterful understanding of political processes and narratives long before he drafted what is regarded as his first autobiography, 'Mein Kampf.'"

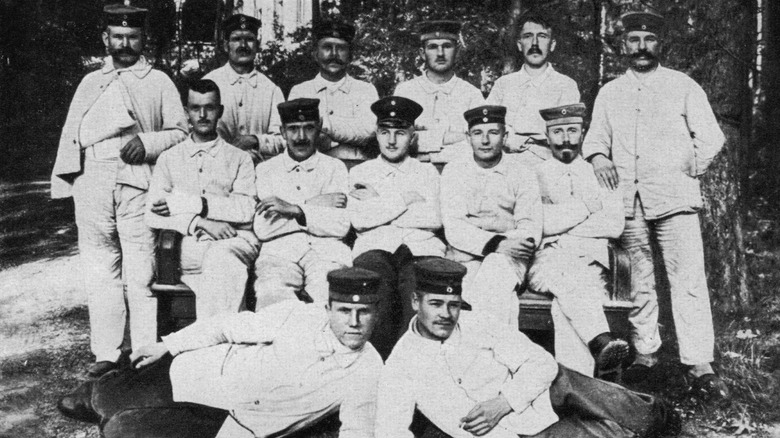

Hitler's World War I heroism

Adolf Hitler famously painted himself as a World War I hero, along with the rest of his unit. He often made claims of braving machine-gun fire, and boasted of having survived a massive gas attack. Perhaps surprisingly, Hitler's claims of his wartime heroism were widely repeated not only throughout his reign of terror but for decades afterward, simply because he had been "an ordinary soldier... there was not an easily available file on him."

That's according to Dr. Thomas Weber, a historian at the University of Aberdeen. He told The Guardian that when he started taking a deeper look into Hitler's wartime service, he found that while Hitler had been a runner as he'd claimed, he wasn't on the front lines — he'd actually been stationed at headquarters, where conditions were described in the papers of one of his fellow regiment members: "I can drink a liter of beer under a shady walnut tree." (That's Hitler pictured above in the back row, second from the right.) And as for that gas attack, historians — including Weber — say that's likely a lie, too. Their evidence includes a doctor's note that cites Hitler as being diagnosed with hysterical blindness (via The Times of Israel), not complications from gas exposure.

And he apparently wasn't as popular with his own regiment as he liked to portray. Records that include diaries and letters refer to him as a "rear area pig." In other documents, his fellow soldiers joke that he'd starve in a canned food factory because he was incapable of opening a can, and laugh at his submissiveness to superior officers.

His life was supposedly spared by a British war hero

According to Adolf Hitler, he had a brush with death on September 28, 1918. That, he said, was when he — injured and unarmed — found himself looking down the barrel of a British gun. He was released, though, and later identified the much-decorated Private Henry Tandey as the soldier who let him go.

Tandey himself spoke about sparing the life of an injured German soldier during the Fifth Battle of Ypres, saying (via History), "I took aim but couldn't shoot a wounded man, so I let him go." Hitler, meanwhile, said, "That man came so near to killing me that I thought I should never see Germany again" (via the BBC), and later picked Tandey's image out of a painting, claiming he was the soldier who had shown him mercy. Sound unlikely? It is.

First, the painting in question (pictured above) is one by an Italian artist named Fortunino Matania, and it depicts events that happened in 1914, not 1918. In addition, documentation uncovered in the Bavarian State Archives show that Hitler was actually on leave from September 25 to September 27, the day before the alleged incident was said to have taken place. Add in the fact that Hitler's regiment was stationed a full 50 miles away from where Tandey was, and the likelihood of the story being true is slim to none. Tandey's biographer, Dr. David Johnson, explained to the BBC, "With his god-like self-perception, the story added to his own myth — that he had been spared for something greater, that he was somehow 'chosen.' His story embellished his reputation nicely."

The nonaggression pact with Denmark

On June 1, 1939, The New York Times reported that Germany had signed a nonaggression pact with Denmark. It was suggested that the agreement was "another proof of Germany's policy of peaceful relations with neighbor States," as well as "earnest both of Germany's peaceful aims and of Denmark's neutrality policy." The German newspaper Lokal-Anzeiger called it "a further advance in the establishment of European peace," and it might have been... had it not been another of Adolf Hitler's lies.

The treaty with Denmark fell in line with the declared neutrality of Norway, Sweden, and Finland, but according to Earl F. Ziemke of the Office of the Chief of Military History, that was part of the problem. The Norwegian city of Narvik was a crucial part of the ore trade, and too important for Hitler to risk losing. Occupying Denmark's military bases would provide an invaluable jumping-off point that would be needed if Germany was going to move into Scandinavia, and by the end of 1939, invasion was pretty much a foregone conclusion, in spite of a September speech in which Hitler declared (via the Yale Law School): "The neutral States have assured us of their neutrality, just as we had already guaranteed it to them."

Only... not so much. Hitler put his stamp of approval on Operation Weserubung on February 29 of the following year, and Denmark surrendered after just a few hours of fighting on April 9, 1940. It wouldn't be liberated from German occupation until May 1945.

His promise to spare women and children

On September 1, 1939, Adolf Hitler stood in front of the Reichstag and gave a speech. In it, he repeated some of the now-familiar rhetoric about how the Treaty of Versailles was unfair to Germany, and he also declared that in the face of inevitable conflict, "I have already made known in the Reichstag... I will not war against women and children. I have ordered my air force to restrict itself to military objectives" (via Yale Law School). How false was that? Very, starting with the invasion of Poland on that very day.

The National WWII Museum cites another speech, this one given to his military leaders on August 22, 1939. There, he had made his true objective clear: Polish men, women, and children were to be killed "with the greatest brutality and without mercy." Death squads were formed, and like the name suggests, they were meant only for killing — particularly the men and women who made it onto lists of people the Nazis deemed most dangerous, along with all Jewish people.

And as for limiting the air force to military objectives, there's no better example of how that went than the Blitz carried out against Britain in 1940. The Coventry City Council counted around 43,000 homes that had been destroyed or damaged, with witnesses sharing stories of children trying to dig their way to safety through solid brick walls, and rivers of boiling butter running from destroyed dairies. The 11-hour raid was said to be retribution for attacks on Munich.

The Gleiwitz incident

It was Adolf Hitler's invasion of Poland that finally and famously dragged much of the rest of the world into war, and bizarrely, that invasion was all built on a carefully constructed lie. It started with the realization that the German army needed at least some sort of justification for turning on Poland, which led to Hitler's orders that a series of false-flag operations be staged by the SS. Although there were numerous incidents — including one where six prisoners were taken from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, dressed as Polish military, shot, and left behind after a staged attack on a customs house — the headline-making one would be the Gleiwitz incident.

On August 31, 1939, a group of SS soldiers — dressed as Poles — took over the radio station in the German border town of Gleiwitz (pictured, now Gliwice). Then, they made an announcement that it was under Polish control. Staging the operation as a short-lived attack and rebellion, they shot and killed a German farmer who reportedly had Polish sympathies and left his body at the station as "proof" of the vicious attack and the station's recovery by German soldiers.

Joseph Goebbels took over from there, and it wasn't long before news of the attack was being broadcast across Europe. Even the BBC picked up on the story via the German News Agency, reporting that Polish insurgents had taken the station briefly, before getting into a firefight with German soldiers. The following morning, German troops were on their way into Poland for retribution... for an attack that Hitler had his SS fake.

Scientific racism and the Aryan bloodline

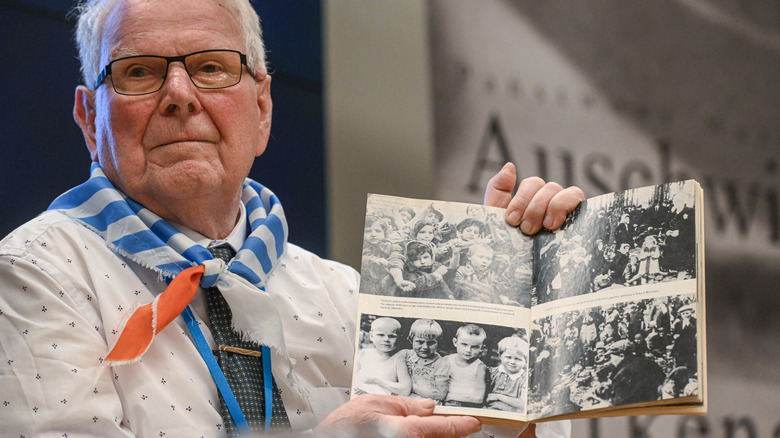

Adolf Hitler's most famous rhetoric involves the Aryan race and "contamination" by the so-called lesser races. In "Mein Kampf," he wrote: "For a racially pure people which is conscious of its blood can never be enslaved by the Jew. In this world he will forever be master over bastards and bastards alone. And so he tries systematically to lower the racial level by a continuous poisoning of individuals." Hitler definitely isn't the first to jump on the scientific racism bandwagon and since he wasn't the last, it's that much more important to stress that there's no basis for any of this in reality. At all.

Still, Hitler's racist and antisemitic beliefs laid the groundwork for the Nazis' ideas and governmental policy, which of course led to mass killings, concentration camps, and the deaths of millions of people. It also led to the establishment of a shocking 44,000 holding sites for those deemed "undesirable." On the flip side of that, there was the Lebensborn program, which was designed to encourage breeding between those deemed genetically suitable for creating the Nazis' ideal Nordic race.

While the roots of scientific racism go back much further than Hitler, it's an idea that's managed to hold on throughout the decades. Science has disproven the ideas of scientific racism over and over again, even finding that on a genetic level, there is no such thing as race. In a nutshell, it's teeny-tiny tweaks in DNA that manifest in outward, physical traits, and at the end of the day, a human is precisely that: a human.

The stab-in-the-back myth

In January 1939, Adolf Hitler gave a speech that included this accusation against the entirety of Germany's Jewish population (via the Jewish Virtual Library): "What they possess today, they have by a very large extent gained at the cost of the less astute German nation by the most reprehensible manipulations." He's talking about what's widely referred to as the "stab-in-the-back" myth, which essentially claims that Germany's World War I defeat was in large part due to espionage, sabotage, and other evil machinations that had taken place largely on the home front.

Other groups that would later be villainized by the Nazi Party — including social democrats and left-leaning liberals — would also be blamed, but Jewish people bore the brunt of the hate. Many of the party's most adamant supporters tripped over themselves in their hurry to buy into the entire idea, as it was an incredibly convenient way to shift blame for Germany's defeat onto an already maligned group and away from the German elite who didn't want to be called out for their failings.

Hitler wasn't the one to invent the stab-in-the-back myth, but he was perhaps the biggest and most dangerous champion of it. And yes, it was a myth that grew some serious legs, in part because it had the support of people like World War I general Erich Ludendorff, who threw his support behind Hitler early on. In a weird footnote, Hitler would later back away from associating with Ludendorff because he was a little too strange. For Hitler.