The Untold Truth Of The Twelve Apostles

You don't have to be a regular attendee of a Christian church to know that Jesus, whom Christians worship as the Son of God and Savior of the World, famously had twelve dudes who followed him around most of the time and listened to him talk. They also frequently asked him dumb questions so he could explain the nature of the Kingdom of God in easy-to-digest analogies. These twelve guys are frequently known as Jesus's disciples, which just means "students," but these particular twelve are more properly known as the Twelve Apostles, which means "those sent out," because they received a literal mission from God to preach to all nations.

While St. Paul is often referred to as one of the Twelve Apostles, he never actually met Jesus during his lifetime. And while notorious traitor Judas Iscariot was replaced among the Twelve Apostles by a guy named Matthias, we don't really know much about that guy. So, just looking at the guys named in the Gospels, here's what we know and what we don't — from canon, apocrypha, tradition, and elsewhere — about the Twelve Apostles of Jesus.

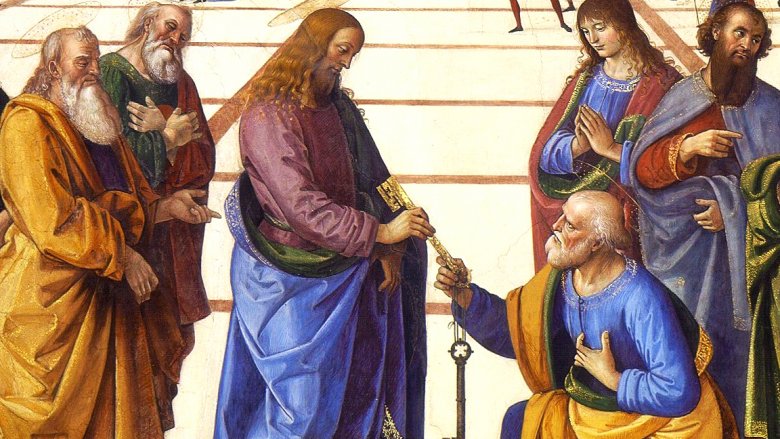

Simon Peter, the Rock

Probably the most famous of the Twelve Apostles, arguably Jesus' #1 guy, is Simon, the son of Jonah (or John), better known by the rad nickname Jesus gave him, Peter. (Jesus probably actually called him by the Aramaic name Kipha, rendered in Greek as "Peter." Both words mean "rock," so, yes, his name is Simon "the Rock" John's Son.) Peter is the focus of a number of famous stories in the canonical Gospels, perhaps most notably the episode in which he (briefly) walks on water, the time he denied knowing Jesus three times, and the time he cut off a dude's ear to keep Jesus from getting arrested. By the time Jesus went back to Heaven, Peter was the first leader of the early church; for Catholics he is the first pope, and for the Eastern church he is the first Patriarch of Antioch. In art, he is frequently depicted holding keys, representing the fact that Jesus promised him the keys to Heaven and Earth. He is also frequently paired with the Apostle Paul in art; you can generally distinguish the two because Paul has a long philosopher's beard (and is usually bald) and Peter has the short beard of a working man.

To see the end of Peter's life, you have to turn to the extracanonical Acts of Peter, which shows him having a deadly wizard battle with the evil Simon Magus before being shamed by the ghost of Jesus into going to Rome to be crucified upside-down, and now an upside-down cross is called a Cross of St. Peter.

Andrew, the First-Called

While there is no shortage of information to be found about Peter — in the canonical Gospels, in the Acts of the Apostles, in the two New Testament letters that bear his name, and the numerous extracanonical books that bear his name — there is considerably less to be found about his brother Andrew. The Gospels of Matthew and Mark tell us that Peter and Andrew (whose name comes from the Greek word for "manliness") were fishermen that Jesus called to be "fishers of men"; the Gospel of John adds that Andrew and the Apostle John were followers of Jesus' cousin John the Baptist and he was the first to recognize Jesus' divinity. For this reason, the Orthodox church calls him the First-Called. Otherwise, apart from being mentioned by name as being present at important events, the only other major thing Andrew does in canon is find the kid with the loaves and fishes that Jesus uses to feed the five thousand.

Outside of canon, however, the Acts of Andrew tells us that Andrew went on to perform great deeds, including raising the dead, magically defeating entire armies by himself, escaping wild animals, doing a magical abortion, summoning an earthquake, and rescuing a fellow Apostle from cannibals. According to tradition, he was crucified on an X-shaped cross, known as a St. Andrew's Cross, like the one found on the Scottish flag.

James, the Son of Thunder

Peter and Andrew were not the only brothers in Jesus' squad. Even better known as a pair are James and John, the sons of Zebedee, who are also known by the incredibly dope nickname the Sons of Thunder, presumably because of their short tempers. By himself, James is often referred to as James the Greater to distinguish him from the other Apostle named James, with "greater" probably indicating that he was older (though he also has a more significant role within the Gospels). James and John were also fishermen called by Jesus on the seashore, and together with Peter, they seemed to be Jesus' main dudes among the Twelve Apostles. Those three were, for example, the only ones present when Jesus transformed into rays of light and the ghost of Moses showed up. James and John also considered themselves important enough that they might both get to sit next to Jesus in Heaven. (Jesus said no.)

The Acts of the Apostles records that King Herod Agrippa had James sworded to death, making him the first of the Twelve Apostles to be martyred. As such, he doesn't have any post-canonical adventures, but that's not to say there aren't non-canonical books attributed to him. The most notable of these is the Secret Book of James, where Jesus reveals to James and Peter the secrets of salvation after his resurrection. (Spoilers: suffering in life is inevitable.)

John, the Other Son of Thunder

There are a couple of New Testament names that are so common, it makes it incredibly difficult sometimes to tell who's who. These names include Mary, Simon, James, Judas, and John. According to the tradition of many churches, John the Apostle, the son of Zebedee and brother of James, is the same person as John the Evangelist (who wrote the Gospel of John), John the Presbyter (who [probably] wrote the three Epistles of John in the New Testament), John of Patmos (who wrote the Book of Revelation), and the mysterious figure from the Gospel of John known as the Disciple Jesus Loved. But there's a chance they're all different people. At least we know for sure that John the Baptist is a wholly different John.

According to tradition, John was the youngest of the Twelve Apostles and managed to outlive all the others through a combination of his relative youth and also never being martyred, though not for lack of trying. The non-canonical Acts of John tell of how someone tried to poison John's wine, but he evaporated the poison by blessing his cup. (This is frequently represented in art by John holding a cup with a snake in it.) His other adventures include raising a married couple from the dead, destroying an altar of Artemis with mind bullets, and magically commanding bedbugs to leave his mat until he's finished sleeping.

Philip, the Dragonslayer and Goat-Converter

Once you get past the two pairs of brothers among the Twelve Apostles, the remaining followers of Jesus start to blend more and more into the background. For example, Philip (whose Greek name means "the dude loves horses") is mentioned as being from Peter and Andrew's hometown, introducing Jesus to another one of the Twelve Apostles, and then, like, being present at other things. He also tells Jesus there's no way they could afford enough bread to feed 5,000 people (whoops). And that's about it. From there, it gets a little tricky to trace his history, as there's a different guy named Philip the Evangelist that it's easy to confuse him with.

Fortunately, the fourth-century Acts of Philip help to fill in some blanks on the traditions of what happened to Philip after the New Testament ends. In it, Philip, together with his biological sister, Mariamne, and his spiritual brother Bartholomew, travels to Greece, Phrygia, and Syria. While on these travels, he manages to convert a talking goat and a talking leopard to Christianity before killing a dragon. However, he converts the wife of the wrong magistrate, who has Philip and Bartholomew crucified on upside-down crosses. (The Cross of Philip, however, is actually sideways.) Bartholomew is released, but don't worry: He gets his own horrible death.

Bartholomew, or maybe Nathanael

The Apostle Bartholomew technically has less about him in the canonical Gospels than most of the Twelve Apostles because he's only named in three out of four Gospels. The Gospel of John never mentions a Bartholomew, but instead talks about a Nathanael, who many scholars think is the same person. Part of the reason for this is that Bartholomew isn't really a proper name — it just means "Son of Talmai" — and the other main reason is that Bartholomew is always paired with Philip in the first three Gospels, and John mentions Nathanael as Philip's friend that he introduces to Jesus.

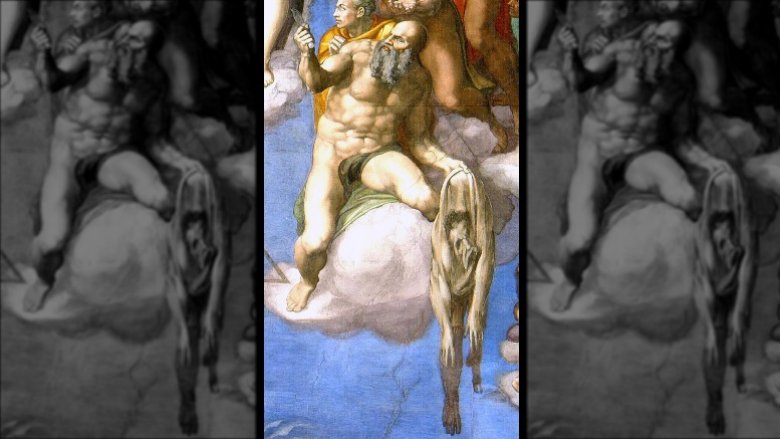

That's about all there is to know from canon, but fortunately post-canonical tradition has our back once again. A particularly amazing text known as the Questions of Bartholomew shows Bart as the only one of the Twelve Apostles willing to ask Jesus the tough questions after his resurrection, and the answers involve Jesus peeling back the ground like a blanket to open a portal to Hell and summoning up Satan so Bartholomew can step on his neck, plus the secret of God and Mary's first date. There are many different accounts of his death, but the best known has him being flayed alive by the King of Armenia, so he is typically depicted in art holding his own empty skin. Michelangelo is believed to have snuck in a self-portrait in the skin of Bartholomew in the painting The Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel.

Thomas, the Doubter and the Twin

Thanks to one episode in one Gospel — John — Thomas has managed to live on in public consciousness far more than most of the Twelve Apostles. Because he said he would refuse to believe that Jesus had been resurrected until he saw him and touched his nailholes, to this day we use the phrase "doubting Thomas." Thomas is also called by the Greek name Didymus; both names mean "twin," so we can reasonably infer that maybe he was a twin. Whose twin, however, is a mystery. (Or is it? Hold on for a surprise.)

There is a bounty of apocryphal literature either about or accredited to Thomas, including the Gospel of Thomas, which contains some very unorthodox sayings of Jesus, and the notorious Infancy Gospel of Thomas, which relates the adventures of Jesus when he was a boy. Thomas' own adventures are told in the Acts of Thomas, wherein he travels to India (the place with which he is most associated even today) and mentally commands a pack of dogs and a lion to eat a guy who slapped him, then battles a dragon and several demons. Tradition also says that he is the one who baptized the Three Kings, and after converting the King of India by raising his brother from the dead, was riddled to death with spears. Sounds pretty loyal for a guy most famous for lacking faith.

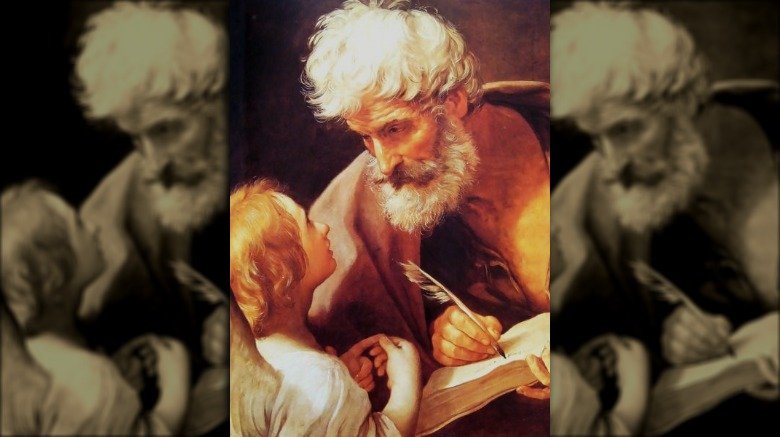

Matthew, the Evangelist and Taxman

The Apostle Matthew is probably more notable for his role as an evangelist more than as one of the Twelve Apostles. The first book of the New Testament is named after him, and tradition attributes that Gospel to him. Within the Gospels themselves, however, he doesn't do much. The Gospel of Matthew says he was a tax collector (considered even scummier then than they are today) who quit his job in the middle of a shift when Jesus asked him to hang out. Mark and Luke tell this story, too, but their tax collector is named Levi, so tradition says the two names refer to the same man. The Gospel of John doesn't mention Matthew at all.

Unfortunately, Matthew doesn't really have any cool post-canon adventures, but a number of non-canonical books are associated with him. As the Gospel of Matthew was written for a Jewish audience, a number of third-century gospels written for ethnically Jewish Christians such as the Nazarenes and Ebionites are attributed to Matthew. There is also an Infancy Gospel attributed to him, but it's largely just a retelling of the more famous Infancy Gospels of Thomas and James. Matthew is believed to have been martyred, but there is no consensus on how or where.

James, maybe Less, maybe Just

James is one of the most common and thus most confusing names in the New Testament. The Apostle James, the son of Alphaeus, is probably but not necessarily the same as the James the Less (younger) mentioned in Matthew and Mark. He might also be the hugely important figure in the early church known as James the Just, aka James the Brother of Jesus. And depending on what kind of church you go to, how literally you take the word "brother" might vary wildly. (According to the Gospels, Jesus had at least four brothers — James, Jude, Joses, and Simon — but churches that believe in the perpetual virginity of Mary say that "brother" in this context means "cousin." Earlier traditions argue they were Joseph's sons from a previous marriage.) If James, son of Alphaeus, is James the Just, then he was the first head of the church in Jerusalem and is the credited author of works as far ranging as the canonical Epistle of James and the amazing Infancy Gospel of James, which tells the story of Mary's childhood up to the birth of Jesus at which a midwife's hand gets burned off testing to see if Mary is still a virgin.

If James the Less isn't also James the Just, then pretty much all we know about him is the tradition that he was crucified in Egypt.

Jude the Obscure

The Apostle Jude gets a variety of names throughout the Gospels, including the name Thaddeus in Matthew and Mark (some manuscripts of Matthew even call him "Lebbaeus who was surnamed Thaddeus). The Gospel of John is quick to point out that he is not the same Judas as Judas Iscariot. In modern times, this distinction is maintained by calling him St. Jude or Judas Thaddeus rather than just Judas. Similar to James the Less, Jude might or might not be one of Jesus' brothers (or "brothers"). If he is, he's probably the author of the canonical Epistle of Jude, which says it was written by the brother of James the Just.

The confusion between Judas Thaddeus and Judas Iscariot has led to St. Jude's famous role as the patron of lost causes: The idea is that Christians would be unlikely to pray to St. Jude for fear of accidentally praying to Judas Iscariot, so they would have to be really desperate to call on Judas.

Jude and Bartholomew are both believed to have been the first to bring Christianity to Armenia, so they are both patron saints of that country. The apocryphal Acts of Simon and Jude instead pairs Jude with Simon the Zealot, and the two travel to Persia, where they were both martyred. Jude is frequently depicted in art holding the ax that killed him.

Simon the What?

The Apostle Simon literally only appears in the Bible in the various lists of the Twelve Apostles, so all we know about him is his name. The problem is, even his name gets messed up in translation. To distinguish him from Simon Peter, this Simon is known as Simon the Canaanite, Simon the Cananaean, or Simon the Zealot. The problem is, Simon wasn't from Canaan or Cana. This is a translation error based on the fact that he is called by the Hebrew word "qanai," which means "zealous," relating to his other nickname, the Zealot. The problem with the name "Zealot," however, is that it has caused many people to believe this Simon was a member of the first-century A.D. political movement known as the Zealots, who wanted to foment rebellion against the Roman occupiers of Judea. The problem is, this movement didn't arise for a couple of decades after the events of the Gospels. So in all likelihood, Simon the Zealot was just, like, really really into the Bible.

There's not much information about Simon outside canon, either: He is said to have traveled to Persia with Jude, where he got sawed in half. As such, he is naturally the patron of people who saw stuff for a living.

Judas Iscariot, the Betrayer (or is he?)

Judas Iscariot (the name "Iscariot" is obscure; it might mean "man from Kerioth" or it might be related to the Latin word "sicarius," meaning "assassin") is one of history's most famous villains, placed by Dante in the innermost circle of Hell, being eternally chewed on by Satan together with the two men who betrayed Caesar. He is of course so well known for handing Jesus over to the Roman authorities — signifying his identity by kissing him — in exchange for 30 pieces of silver that the word "Judas" is still used in many contexts to point out the treachery of any number of people, animals, or things. Matthew says Judas regretted his betrayal and hanged himself, while the Acts of the Apostles says he used the silver to buy a field where he tripped and then exploded like a blood Gusher.

Judas' motivation for betraying Jesus are not fully known. Luke and John say he did it under the influence of Satan; more modern interpreters believe that Judas was disappointed that Jesus was not a more militant political messiah. The recently recovered Gospel of Judas, however, claims that Judas was in fact Jesus' most loyal follower. Since Jesus' crucifixion was a necessary step toward salvation, it says, Jesus actually asked Judas to betray him so his mission might be fulfilled, and Judas willingly took the eternal hit to his reputation.