Clara Bow: The Untold Truth Of Hollywood's First 'It' Girl

Most movie buffs have heard the phrase "Hollywood's newest 'it' girl" used to describe the industry's hottest ingenue, but even die-hard cinephiles might not be acquainted with the fascinating personal history of Clara Bow, the silent film star who inspired the term.

Born in a Brooklyn tenement at the turn of the 20th century, Clara Bow was an unlikely leading lady. Her childhood was defined by poverty, abuse, and loss, and she had no connections in the film or theater worlds to give her a leg up. What she did have going for her, though, was plenty of talent, determination, and beauty, and she used all three to her advantage, so much so that by the time she all but withdrew from Hollywood at age 28, she'd made close to 50 silent films and more than 10 talkies.

The "it girl" phrase likewise has an interesting backstory. Writer Elinor Glyn argued that any actress said to have "it" would be steeped not only in sex appeal but a winning lack of both self-consciousness and vanity. Then Paramount made a film of Glyn's novella, "It," with Bow in the lead role, and thereafter the red-haired starlet was known as "the 'It' girl." Later, countless young actresses would be labeled as such and would find out the hard way, as Clara Bow did, that having the elusive "it" factor could prove both a blessing and a curse.

The flapper wars

Clara Bow was one of the first actresses to portray a so-called "flapper" on the big screen and, by doing so, earned herself a stable of rivals, including Colleen Moore and Louise Brooks.

Flappers emerged in the 1920s in part as a reaction to Prohibition and quickly became emblematic of the so-called Jazz Age, an era of excess and free love and F. Scott Fitzgerald. With their tight dresses and bobbed hair and tendency to dance on tables, flappers horrified the prudish American establishment. They also made for fantastic movie fodder, and Clara Bow became a household name, thanks primarily to her portrayal of free-living and stubbornly boisterous flappers in films like "The Plastic Age" and "The Dancing Mothers."

She also earned herself a frenemy in fellow flapper Colleen Moore, who reportedly so resented sharing the screen with Bow in the film "Painted People" that she made sure to cut Bow out of all the film's close-ups. Bow quit the movie after three weeks of filming in order to have sinus surgery, and that put its distribution way behind schedule. It's possible Bow's decision to ... bow out of the film, was completely innocent. It's also possible that it was her way of getting even. Clara Bow was many things, but shrinking violet was not one of them.

Clara Bow didn't look for wedding rings

Either Clara Bow didn't look for wedding rings, or she totally did and the looking was part of the fun. Bow was infamous in Hollywood for her many conquests and complete lack of sexual shyness. She even went so far as to make sure there were no restrictive morals clauses in any of her contracts. During her short but incredibly prolific career, Bow was romantically linked to a number of her co-stars, including Gary Cooper, Gilbert Roland, and Bela Lugosi, and she sometimes strung along three men at a time. At the height of her fame, she got engaged to "five men in as many years."

In one of her more infamous episodes, she flirted scandalously with a married ex-judge at a party thrown by B.P. Schulberg, the president of Paramount Pictures. The judge, who had lost his seat for coming out in favor of premarital sex, was at the party as a journalist to interview Bow for Vanity Fair. Clara greeted the judge with a kiss — in front of his wife, no less — and then pulled him onto the dance floor, where she proceeded to unzip his pants. The judge was taken aback by her forwardness, but Bow, in typical no-nonsense fashion, questioned his cred: "If he likes all that modern stuff, how come he's such an old stick-in-the-mud?"

Nothing — not wives, not rings — could stop Clara Bow from living her best life.

Clara Bow mothered her own mother

Bow spent much of her rough-and-tumble childhood tending to her mother, Sarah, whom Clara idolized even though she was an embittered, mentally ill epileptic. According to a three-part interview Bow gave Photoplay magazine in 1928, Sarah was a beautiful and tragically unhappy woman who hated the often ugly and circumspect days she spent in a Brooklyn tenement. Prior to Clara's birth, Sarah lost two children. She reportedly tried to throw one of the dead bodies right into the trash.

Clara was forced into the role of nursemaid from a young age, and she lived in fear that her mother would die in front of her during a seizure. Sarah Bow grew increasingly delusional with the years and was deeply disturbed by her young daughter's forays into acting and show business. In the Photoplay interview, Bow said that at one point her mother put a knife to her throat and claimed that movies were evil. Sarah thought it her duty to end her daughter's life so she would sin no more.

Clara divided her teen years between running to auditions and tending to her mother, and she was on a film set when her father broke the news of Sarah's death in a mental institution at the age of 43. Despite the fact that Sarah was often cruel to her, the loss of her mother was a devastating blow and during the funeral Clara Bow tried to throw herself into her mother's grave.

From abuser to manager

Clara Bow's father was, by all accounts, a drunk, philandering, ne'er-do-well who would often beat Clara as a way to end a fight with her mother. Clara, though, loved him unconditionally. In her telling, he was a brilliant man who couldn't catch a break, and the family had to move from one cramped apartment to another, often forced to rely on the kindness of relatives for shelter, clothing, and food.

Later, as his daughter's beauty and talent became apparent, Robert Bow pushed her into show business, often against the wishes of his wife. Clara told Photoplay magazine that he wanted Clara to pursue acting because, as he saw it, it was no more dangerous than office work.

As Clara Bow's career began to take off, she trusted her financial affairs to her former hairdresser and friend, Daisy DeVoe. Clara began to suspect that DeVoe might not have her best interests at heart, though, especially when DeVoe began bad-mouthing Robert. Then Robert flew out from New York to Los Angeles to be with Clara, and while she planned to give him the cold shoulder, she couldn't. She melted in his presence, happy to be among her people again, and he soon became her de facto manager. Perhaps it's not shocking that Robert Bow then used his daughter's fame to try to pick up girls, telling anyone he could that he was Clara Bow's father and capitalizing on her appeal to the last.

Clara Bow made 15 films in one year

At the outset of her career, Clara Bow's flame burned bright, so bright, in fact, that she appeared in 15 films in 1925 alone. Three years later, she received 33,727 fan letters in one month, an industry record and perhaps, according to the Washington Post, a human one as well.

Bow's appeal was many faceted. In accordance with the writer Eleanor Glyn's definition of "it," Bow appealed to both men and women. Not only did she have the perfect flapper face and figure, she also radiated fun and excitement and spontaneity. On-camera, she was irresistible. Off-camera, she was 100 percent real at all times. Take, for instance, her response to one of her more famous break-ups: "I cannot marry Harry Richman as I am expecting a nervous breakdown."

Many of the movies she made in 1925 are forgettable (see "The Lawful Cheater," a crime drama about a gang of misfit crooks who see the error of their ways, and "Parisian Love," in which Bow's character claims to be of the Apache nation), but several are enduring artifacts of a time and aesthetic she helped shape.

How Clara Bow inspired Betty Boop and started a henna craze

Clara Bow's hourglass figure and natural exuberance on screen were, in part, the inspiration for Max Fleischer's animated temptress, Betty Boop. The other women who gave Fleischer the idea for Betty Boop included the African American cabaret singer "Baby" Esther Jones and Helen Kane, a popular white singer at the time.

It was Betty Boop's unapologetically sexy nature and her refusal to give in to the uptight mores of her time that perhaps owe the most to Clara Bow, who was likewise staunch in her insistence on being herself always, no matter who it might offend or inconvenience.

Women all over America wanted to emulate Bow's devil-may-care attitude, and they wanted to look like her, too. When it got out to the movie-going public that Bow had red hair, there was a run on henna hair dye. So many bottles were bought up, in fact, many stores ran out. It all came as a surprise to Bow, who grew up thinking of her Titian (orange-brown) locks as a handicap.

Clara Bow's husband ran for the House of Representatives

Bow eventually retreated from Hollywood to live on a Nevada ranch with her husband, Rex Bell, also a former actor. Then Bell tried to drag her into public life again when he ran for the U.S. House of Representatives in 1944. Bow had been hounded by the press for several years at this point. She was finished with fame and disgusted with the press, who, at the height of her career, slung mud at her from all sides, painting her as a drunken sex maniac who slept with her own dog. When Rex announced his campaign, Bow attempted suicide. Her sons found her passed out on the floor of their home, having overdosed on sleeping pills.

Despite the very real and sad drama surrounding his wife, Bell went on to make a career out of politics, and a decade after his first campaign, he was lieutenant governor of Nevada. By that time, though, he and Clara were living apart — she in a bungalow, close to her California psychiatrist, and he in Nevada with a blond divorcee 10 years Clara's junior. Bow and Bell were still married and had two sons together, but Bell's pursuit of politics effectively ended their relationship. It was a sad end to a romance that began when Bow and Bell (whose real name was George Beldan) met on the set of "True to the Navy" in 1930.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org

Like mother, like daughter

Clara Bow had a series of breakdowns beginning just before she left Hollywood, and her husband, Rex Bell, ended up committing her to a sanatorium, just as her father had done to her mother and her grandfather had done to her grandmother before her.

Clara Bow's roller coaster personal life and struggles with mental illness earned her the cold nickname "Crisis-A-Day Clara," but that was an unfeeling industry placing blame where it didn't belong. It's likely that Bow suffered from schizophrenia, which can develop later in life, and that her mother did as well. (Her grandmother was driven mad by her husband's constant beatings, according to David Stenn's "Clara Bow: Runnin' Wild." And when a census worker came to Bow's grandparents' house to survey the household, her grandfather locked his wife up in a closet and claimed to be a widower.)

Many critics assumed that Clara Bow's career was torpedoed by the advent of talkies and her strong, Brooklyn accent. She'd obviously flourished as a silent movie star, so that was a natural assumption, and Jean Hagen's broad but hilarious turn as Lina Lamont in "Singin' in the Rain" is a send-up of Clara Bow and her fall from grace. In reality, though, Bow was sidelined not by her lower-class roots but by mental illness and a burning desire to escape the glare of the spotlight.

Clara Bow started poor, got rich, then ran into money trouble

Clara Bow grew up impoverished, often wearing her mother's old worn out shirtwaist dresses done over and going hungry night after night. When asked to elaborate on her youth and life with her parents, she said, "We just lived, and that's about all." It's no surprise then that when she got a taste of fame and money, she didn't always manage it well. Gambling debts and even rumors of debts followed her everywhere.

In September 1930, Clara Bow's alleged debts caught up with her to the point that executives with Paramount Pictures felt a response was needed. B.P. Schulberg, Paramount president, told the Cornell Daily Sun that reports of Bow's owing almost $14,000 to a Lake Tahoe casino were not the studio's problem but Bow's alone.

The scandal didn't just implicate Bow, though. Will Rodgers, the comedian cowboy from Oklahoma, was seen having dinner with Bow and her then-boyfriend, Rex Bell, the night Bow supposedly ran up the debts. Rodgers was also rumored to have introduced Bow to James McKay, the owner of the casino in question. Bow denied the story, saying she always paid her debts promptly. Rodgers also denied it, saying he never gambled because everything was fixed for the house.

Clara Bow and the court of public opinion

In 1929, Daisy DeVoe — Clara Bow's hair stylist-turned-manager and (supposedly) best friend — tried to blackmail Bow by going public with scandalous reports of Bow's bad behavior. DeVoe accused Bow not only of drunkenness and loose morals but drug use and bestiality. (There was talk at the time that Bow had an unusually close relationship with her dog.)

DeVoe's story, clearly a hit job from the beginning, gained credence when a Los Angeles-based tabloid, the Coast Reporter, took it up and devoted 60 pages to detailing Clara Bow's supposed exploits. The piece, entitled "Clara's Secret Love-Life as told by Daisy," gave DeVoe (whose real name was DeBoe) a platform from which to spew ugly lies about Bow, already the subject of salacious Hollywood gossip. Robert Girnau, publisher of the Coast Reporter, sent copies of the magazine to judges, PTAs, and the first president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, hoping, as DeVoe obviously was, to cash in on Bow's vulnerabilities. He even tried selling the entire paper to Bow's husband, Rex Bell, for $25,000, but Bell refused to play his game. Girnau eventually went to jail for sending lewd material through the mail.

DeVoe, too, served time — 18 months to be exact — but not for extortion or being the world's worst best friend. For stealing Bow's fur coat.

Clara Bow does the USC football team (not really)

After Clara Bow moved to Los Angeles and became one of America's first and most beloved movie stars, people began spreading rumors that she often invited the entire University of Southern California football team over to her house for wild, out-of-control adult games. In his tinsel town expose, "Hollywood Babylon," Kenneth Anger joined the chorus, claiming that Bow had an insatiable appetite for fullbacks, halfbacks, and tight-ends. However, like much of the gossip surrounding Bow's choices in the bedroom, this ridiculous story turned out to be completely false.

It was true that Bow was an unabashed fan of USC football, and she did go out on a date with the team's standout quarterback, Morley Drury, but, according to Drury, nothing ever happened at Bow's house parties beyond eating and innocent flirting. The parties took place after each Trojan home game and included a little dancing but no hanky-panky. Clara Bow eventually moved the parties out of her house and into a hotel room on the insistence of her father, who, despite his own checkered past, worried about the impropriety of such events. Later, she hosted the team once a year and then not at all.

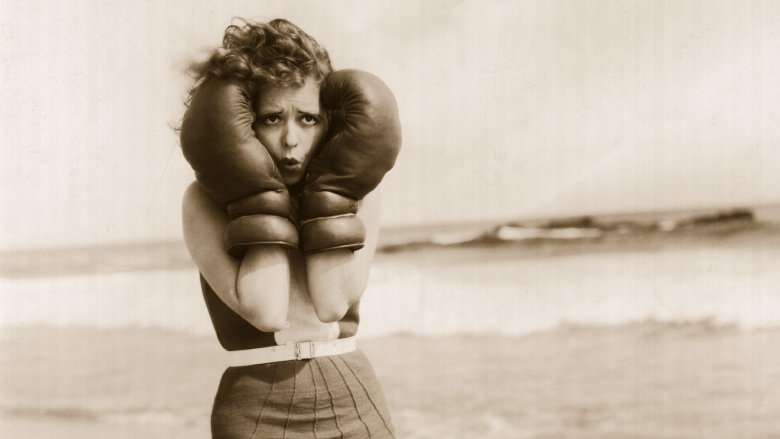

Clara Bow was a tomboy and an athlete

Clara Bow wasn't just a beautiful, talented, high-spirited actress. She was also a natural athlete. Growing up poor in Brooklyn, she gravitated to the boys in her neighborhood and school, eschewing dolls and pretty clothes in favor of games of stick ball and impromptu foot races. In fact, that's where she claims to have gotten her long, toned legs — from running. And she got her strong right arm from pitching to boys in the alleys. She used that arm to defend her first friend, a little boy named Johnny she used to walk to school with. Any time Johnny got bullied, Clara Bow was right there, ready to throw down.

In 1919, she enrolled in the Bayridge High School for girls, but she didn't fit in there. She didn't have the right look, the right clothes, or the right demeanor. As a teen, she was so interested in sports that she planned to go on to train to be an athletics instructor, and her cousin, Homer Baker, a U.S. national half-mile champion, inspired and coached her to winning five medals on what she called "the cinder tracks."