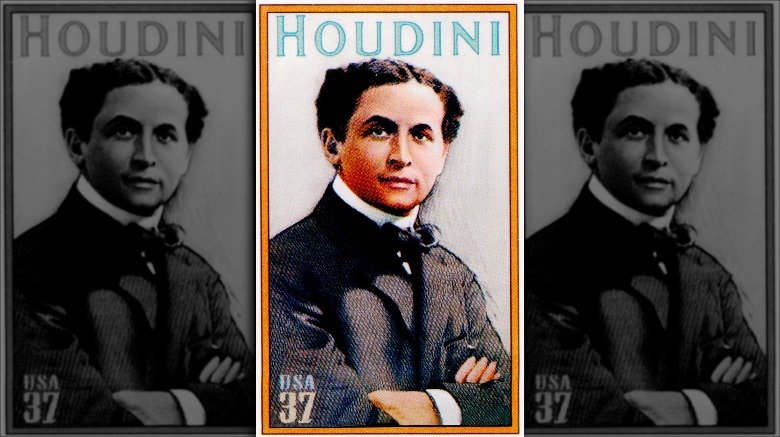

The Life And Death Of Harry Houdini

Born into complete poverty and obscurity, by the time he died, Harry Houdini had become one of the most recognized magicians, escape artists, and stage performers of all time. Throughout his lifetime, he'd devise a library of new magical techniques that would forever change how stage-magic was done. Along the way, he also forged the prototype for a new kind of magician — a prestidigitator who made his craft real and relatable outside of the stage. He hung from cranes. He buried himself alive. He got himself incarcerated. Harry Houdini was a master of publicity with a knack for making sleight of hand magic seem both gritty and real. He was also an inventor, a pioneer aviator, a (failed) movie star, and a passionate advocate for rational skepticism.

Who was this living legend? How did an impoverished shoeshine and grifter on the streets of New York City become The Great Harry Houdini?

Ehrich, prince of the air

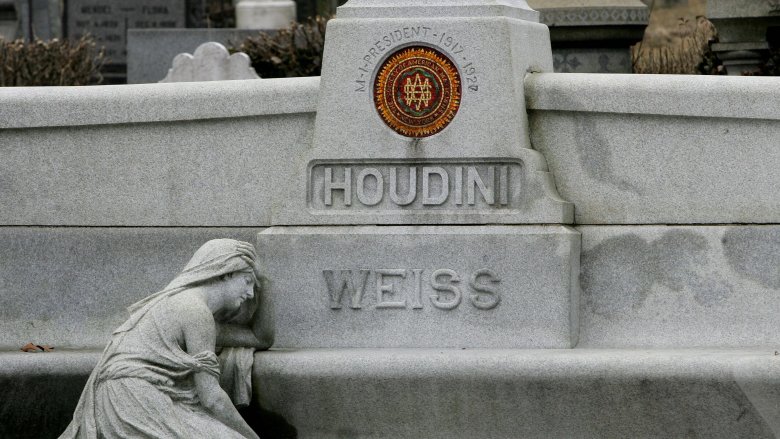

The story of Harry Houdini begins humbly. The Great Harry Houdini was born Ehrich Weisz in Budapest in 1874. One of seven children, Ehrich emigrated to the US with his family in 1878. According to Houdini: His Life and His Art, it was not an easy life for a poor Hungarian immigrant. As a child, Ehrich sold newspapers, shined shoes, and did his best to bring in whatever money he could to support his family. Somewhere along the way, young Ehrich also acquired a few street grifting side hustles. According to Houdini's biography on U-S-History.com, at 6-years-old he could run the three cup scam well enough to fool passersby out of a few coins. A natural athlete, he also picked up good acrobatic and tumbling skills. One day the circus came to town, and (as all good origin stories go) Ehrich was on a mission. Showing the first streak of chutzpah that'd serve him well his whole life, Ehrich strutted his stuff for the circus manager, and the future Harry Houdini got his first big break. In 1883, at just 9-years-old, Ehrich performed his first act as a trapeze artist. His majestic stage name: "Ehrich, the Prince of the Air."

By 11-years-old, Ehrich had a reputation as a performer. He was strong and wiry for his age, with a strength and dexterity honed through years of physical performance. He'd also commenced a sensible apprenticeship as a locksmith. All the ingredients were now in place.

The birth of Harry Houdini

Ehrich read voraciously, greedy for any new insight he could find into the art of performing. Wild about Harry describes 15-year-old Weisz's discovery of a book that would change his life: the memoirs of a barely remembered sleight of hand magician, Jean Eugene Robert-Houdin. He was hypnotized. Weisz decided his future lay with magic and he chose a new stage name to honor his role-model, idol and mentor. He became Harry Houdini.

First with his friend and then his brother, Harry Houdini set about building a magic act. He tried almost every flavor of magic in those years, but he settled on card magic, billing himself (with no false humility) as Houdini, King of Cards. There was one small problem. He wasn't good. Fellow practitioners of the prestidigitation arts viewed Houdini as competent at best. According to Harry Houdini: The world's most famous magician, in 1896, Houdini placed an ad to sell all his tricks and props for a meager $20. No-one was interested. He hovered here, on the edge of historical obscurity, for another two years.

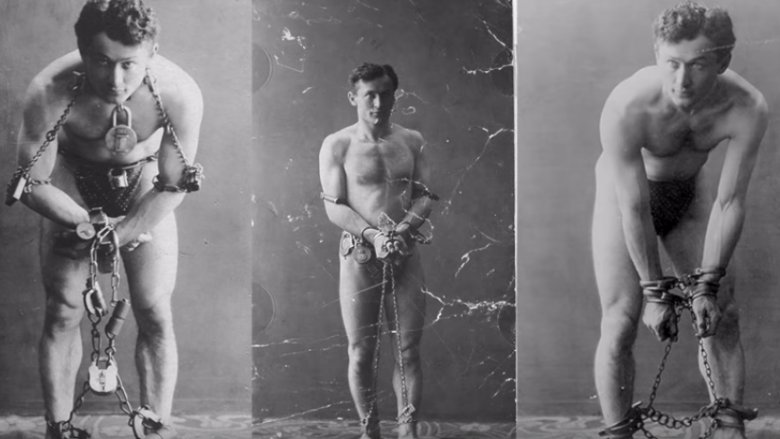

However, the not-yet Great Houdini was street smart and resourceful. By 1898, Houdini had reinvented himself as the Handcuff King, and the man whom no restraint could hold. In this domain, as they say in the classics, the kid was a natural. By 1899, Houdini was an A-list Vaudeville Act. He'd successfully escaped the clutches of poverty. Ehrich Weisz was gone and the Great Harry Houdini was born.

The handcuff years

By 1900, this once impoverished Hungarian immigrant was offered his first European tour, according to The Vintage News. But tastes were different in Europe, and Houdini encountered a lukewarm reception. And it's right at this moment of possible failure that the first important truth about Houdini becomes crystal clear: Houdini wasn't just an escape artist on stage. He was an escape artist in real life, too. When something locked him down, Houdini found a way to get free.

Houdini discovered a novel way to grab the public's attention. At each town he performed in, he staged a public confrontation with local police. In front of a goggling press, he challenged the constabulary to restrain him as best he could. Then he'd escape. Suddenly, Houdini wasn't just another stage magician. He was the guy who no prison could contain, and better yet, he could thwart the bumbling police in the process. He captured imaginations, and the Handcuff King had become a European sensation.

A fun little side-note to Houdini's knack for publicity at the police's expense: One police officer accused Houdini of bribery. Houdini sued, and legend has it he won the case by successfully breaking into the judge's safe. Houdini later admitted the judge had simply forgotten to lock it. As Houdini later said, "it's not the trick. It's the magician."

Dicing with death

By 1907, other magicians were catching on. Houdini may have been one of the best handcuff magicians in the world at this time, but competitors were rapidly closing ground. As imitators clamored to cash in on his phenomenal success, Houdini's act gradually became stale. Handcuffs would no longer cut it.

But Houdini was stubborn. And ever the one to wriggle out of life's limitations, he set about expanding his act in ways audiences hadn't been seen before. Thought Co. says in 1908, Houdini introduced a dramatic new escape stunt which he called (kind of unimaginatively) the Milk Can Escape. The act was simple but startling. Houdini would locked himself inside a sealed milk can filled with water. Then, after a tense wait, he'd fling the lid aside and emerge victorious. It was unusual, it was scary, and it was an immediate audience favorite.

Houdini's prodigious strength combined with his deftness with locks placed him in untouchable territory. He had a unique combination of skills other magicians couldn't easily plagiarize. But it was more than that. Houdini had found the secret formula that would make him unique for the rest of his performing life, and which would one day elevate him to magician immortality. He realized that the ultimate power of his act lay in cheating death. He danced where other performers feared to tread.

The makings of a master

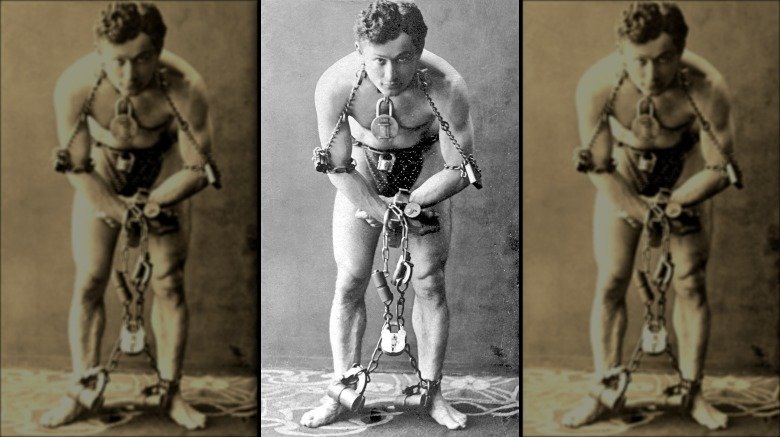

Houdini still had a long way to go in his career, but by this point in his life, all the ingredients of his escape mastery were now in place. Through years of practice and training, Houdini possessed an unbeatable combination of athleticism and dexterity. According to Houdini: His Life and His Art, Houdini could enlarge the girth of his chest and shoulders using muscle control. This gave him the gift of just a few extra inches of wiggle room while extricating himself from upper body confinement. He'd also become (or perhaps always was) bow-legged. Some magicians speculate his unusual legs allowed Houdini to slip rope ties that would completely immobilize a regular body shape.

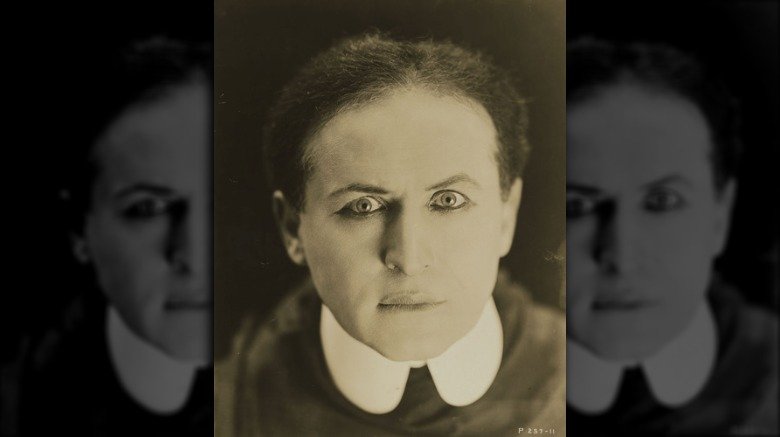

Most importantly, people underestimated Houdini. They had his whole life. He was small, even for the day. At around five-and-a-half feet tall, Houdini just didn't seem capable of the feats he could achieve. But, as Biography.com attests, he was known for his uncanny strength. Even in still pictures, Houdini is slightly odd to look at. He's squat yet strangely poised. He's fine-boned yet sturdy. For the time, his muscle definition is unusually pronounced. And there's also that odd look of his, a look of piercing intensity.

Those who saw him perform agreed with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's assessment. He included Houdini in a Sherlock Holmes novel where the escape artist is described as carrying himself with "imperious self assurance." He'd become a master of his art.

Houdini and obsession

Through years of hard work, Houdini had become an international act and a household name. He'd made it — and his place among the all-time greats of stage magic was assured. But whether fueled by fear of his rivals or something innate to his personality, Houdini wasn't content. He looked for new angles, new diabolical scenarios, and most of all, new ways to thwart death.

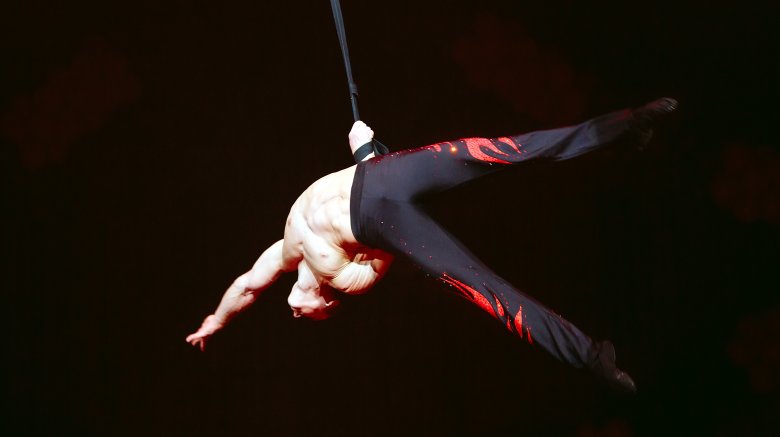

This constant striving led to the development of arguably his most recognizable trick: the Chinese water torture cell. In this act, Houdini would be straight-jacketed and suspended upside down in a vat of water. In front of a terrified audience he would struggle loose, holding his breath for minutes at a time.

These days, the idea of a magician appearing as though they're in danger is almost cliched. It's expected, and the audience knows that the risk itself is manufactured for dramatic effect. But Houdini's acts weren't all smoke and mirrors. He created drama and tension through placing himself in true mortal peril. According to Wild About Harry, in 1917, Houdini nearly died of suffocation in an act where he was buried under six feet of dirt. But even that close shave wasn't enough to deter him. Now a mature performer of 41, Houdini had nothing to prove to anyone. But he remained obsessed with taking one step closer to death — of upping the ante for his audience, come what may.

Harry Houdini's war against spiritualism

As the 1920s rolled around, Houdini was a living legend, not just among his ardent fans but within the stage magician community. Now elevated to the illustrious position of President of the Society of American Magicians, Houdini gained something he'd never had as a young man: influence. It was at this stage of his career that Houdini doubled down on what would become a life-long war against spiritualism. Houdini's obsession with debunking the tricks of psychic performers placed him at odds with the magical community.

Houdini's crusade culminated in a public falling out with his close friend, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. According to The Guardian, Doyle was an ardent believer in the supernatural, and the men had a very public spat when Houdini described one medium of the time as a "human leech." It was an odd chapter in the life of these two famous figures. A stage magician whose life revolved around misdirection became a staunch advocate for skepticism, while the inventor of Sherlock Holmes, a character of pure rationality, became the poster child for blind faith in the supernatural. The two titans remained at odds for the rest of Houdini's life.

Houdini's fear of plagiarism

It wasn't just disgust with scams that drove Houdini in his years of ascendancy as the Dumbledore of US stage magic. He also waged a career-long battle against people who would steal his ideas.

Houdini left a string of odd patent applications with patent offices in the US, the UK, and Germany. Some of these applications were for unique kinds of locks. Smithsonian records others were for far more obscure and revealing applications, like a watertight chest that could be locked and concealed inside a larger chest. Intriguingly, these and similar patent applications were abandoned. Stage-magic historians think that Houdini realized at some point that patents were public record. While filing a patent may have ensured his legal right of ownership over an idea, it was also a surefire way to reveal the inner workings of his methods, props, and stagecraft to other magicians. True to form, Houdini found a workaround. Instead of patenting his work, he copyrighted it. This allowed him to own a trick without revealing it.

There are some unusual exceptions. In 1921, Houdini filed a patent for an improved diver's suit with quick release fastenings. According to the patent, the suit "permits the diver, in case of danger ... to quickly divest himself of the suit while being submerged." It's still used today.

No one can be good at everything

Houdini is known for his extraordinary successes, but when he fell flat on his face it was equally entertaining. An avid aviator, Houdini hatched a plan to become the first person to fly a plane in Australia. He had a custom craft shipped there and in 1910, Houdini successfully got it off the ground for a grand total of three minutes. The news coverage of the day wasn't exactly glowing, but the papers dutifully acknowledged his achievement and everyone got on with their lives. But Houdini's achievement was stripped from him months later, when a rival aviator conclusively proved he'd achieved the deed months earlier than the magician. Houdini was despondent as his career as an aviation pioneer came to an abrupt end.

Another rare Houdini fail came when he attempted to cash in on the newfangled cinema craze. In 1918, the golden years of vaudeville performance were waning. Realizing he was losing his audience to the silver screen, Houdini starred in two extremely lackluster movies. In The Grim Game (1919), Houdini is framed for murder and runs around escaping various suspiciously staged predicaments. It is not a good movie. In Houdini's own words (which would be prophetic of cinema in the century to come), "No illusion is good in a Film, as we simply resort to camera trix and the deed is did."

Houdini's untimely demise

Accounts of the last days of Houdini vary slightly in their particulars. According to What Killed Harry Houdini, in 1926, a now well past his prime 52-year-old Houdini fractured his ankle setting up stage equipment. Ever the showman, Houdini nevertheless entertained a steady flow of fans, eager to behold the legendary showman. On the Montreal leg of his tour, a fan (J. Gordon Whitehead for the record; may his name live in infamy) asked if it was true that Houdini could withstand powerful blows to his midriff. When Houdini confirmed, Whitehead laid into the reclining magician with several powerful blows. Observers say Houdini likely had no time to prepare, and appeared to be in pain afterward.

Battling two injuries, Houdini nevertheless persisted with his busy performing schedule. At the end of a performance soon afterward, Houdini collapsed. Within a few days, Houdini was diagnosed with a ruptured appendix and acute peritonitis. By then it was too late.

United Press International archival documents record Houdini reassured his wife in his final days, saying, "I'll get out of this the way I always get out of everything." But he succumbed quickly. On October 31, 1926, Houdini died. His last words were "I guess I'm all thru fighting."

A weird postscript: Rosabelle believe

There's a strange epilog to the life of Houdini, renowned skeptic and escapologist sans pareil. Before he died, Houdini made an odd pact with his wife, Wilhelmina "Bess" Rahner. He told her he'd do everything in his power to escape the embrace of death by sending her a message from beyond the grave: "Rosabelle Believe," a nod to one of her favorite songs. This odd pact gained much publicity, and according to Skeptical Inquirer, this culminated in a prominent medium and Bess announcing in shared statements to have successfully received the message in a seance. This was later dismissed as a hoax.

Despite this less than desirable press, Bess conducted seances to contact Harry for a decade. In 1936, she made her last failed attempt. According to Time Magazine, she announced, "Ten years is long enough to wait for any man." Despite Bess (kind of understandably) calling it quits, the seance is still going strong. Every year, on the anniversary of Houdini's death, stage-magicians gather to offer Houdini one last chance at stealing the spotlight. It's an odd tribute to a man who spent his life scoffing at performers claiming connection with the beyond.

Why would Houdini indulge in something he so passionately condemned his whole life? Perhaps he believed that if anyone could wriggle out of death's embrace, it might as well be him? Despite repeated attempts to contact Houdini, to date he has chosen not to comment.

Harry Houdini lives on ... kind of

Almost 100 years after his death, Houdini remains a household name. Whether you're in downtown Tijuana or Turkmenistan, ask someone off the street to string off a handful of famous stage magicians and Houdini's name is almost certain to get a mention. He also remains immensely significant in magical circles.

As President of the Society of American Magicians, Houdini left an indelible footprint as the one who standardized magic practice, making it a codified movement. Wherever he traveled, Houdini made a point of recruiting local magic clubs into the society fold, and this created a shared vision of the key principles of mutual professional respect which stage magic still holds dear today.

Houdini is an icon. Like Chaplain, he's the little guy who always came out on top. Like James Dean, he's the rebel who stuck it to the man. But most of all, people were captivated by his bravery. He was fearless and glittering with determination. Houdini's great public rival, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, said this of his friend turned life-long enemy: "He had the essential masculine quality of courage to a supreme degree. Nobody has ever done and nobody in all human probability will ever do such reckless feats of daring."