Classic Movie Monsters That Are Nothing Like The Character They Are Based On

Moviegoers love monsters. For as long as people have been planting their butts into seats and gazing up at the big screen, they've delighted (or screamed) at the antics of giant ants, extraterrestrial squid beasts, rampaging lizards, and bloodsucking vampires. Sometimes, one of these monsters will survive through so many films that viewers start forgetting that they're supposed to be a bad guy, not the hero. Yes, here's looking at you, Jason Voorhees.

Quite a few of cinema's most iconic monsters have been adapted from novels, short stories, and mythological works. However, movies always deviate from the book, and when these unholy creatures and supernatural madmen were first brought from the printed page to the big screen, many of them were altered beyond recognition. Between personality shifts, visual adjustments, and outright misunderstandings of the author's intent, most of these adapted movie monsters might as well have different names entirely. Here are the guiltiest offenders.

That square-headed dude isn't the real Frankenstein's Monster

Mary Shelley's 1818 novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus is one of the most important works in literary history. Frankly, if you enjoy science fiction today, you owe Shelley a debt of gratitude. Which makes it all the weirder that, as Den of Geek argues, nobody ever faithful adapts her book.

In the novel, Victor Frankenstein's great flaw is not creating a monster, but rather, abandoning it at first sight: upon glimpsing his monster's jaundiced eyes, lustrous black hair, and translucent yellow skin — which reveals muscles and arteries beneath — Victor basically hightails it like a complete jerk. Meanwhile, Shelley's creature is an intelligent, eloquent, and emotional being, desperate for love, who only becomes a "monster" because its every attempt at human connection leads to being beaten, dismissed, and abused. Shelley's book has no lumbering, green-skinned behemoth of childlike intelligence. No neck bolts. Nobody says "It's alive!," and there's not even a conclusion involving villagers with pitchforks and torches, since the book's ending sees Victor pursuing his monster deep into the Arctic, whereupon he freezes to death.

How did this happen? The monster whom popular culture calls "Frankenstein" today comes from the 1931 Universal film, starring Boris Karloff, which according to Cinephilia and Beyond took its story beats from a prior (unfaithful) Frankenstein stage play, rather than the book. Now, to be clear, the Karloff film is amazing. A true classic of the genre. Honestly, though, doesn't Shelley's real story deserve more airtime?

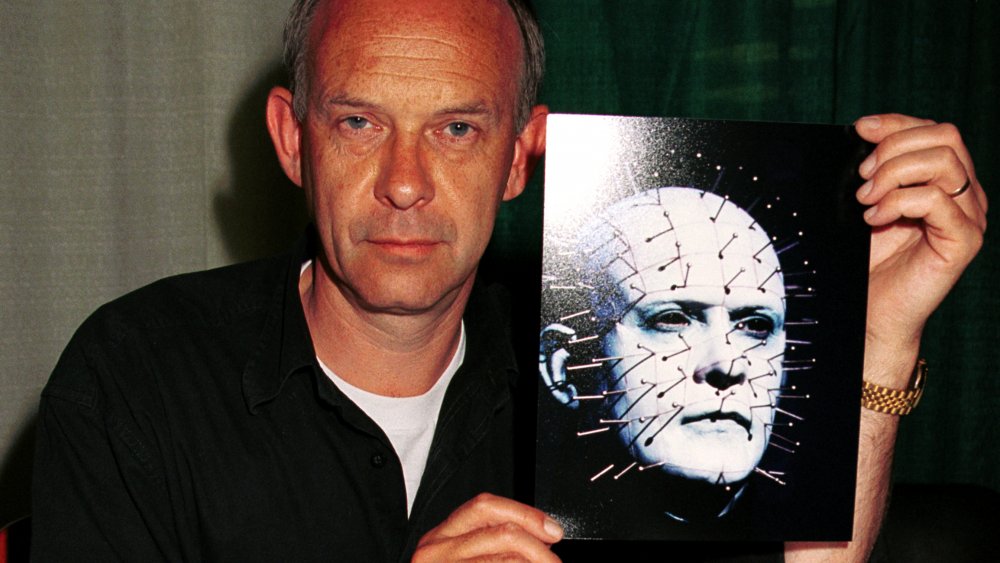

"Pinhead" wasn't in Clive Barker's plans

When you think of Hellraiser, you probably envision Doug Bradley's Pinhead threatening to "tear your soul apart" while he rips your flesh out with mystical death hooks. Pinhead is one of the cinema's most iconic monsters, which makes it easy to forget that he and his creepy Cenobite crew appear in the first movie for, what ... five minutes, tops?

And in Clive Barker's original novella, The Hellbound Heart, the spiky-faced demon is nothing like the one you know. The literary character is intentionally framed as androgynous — if anything, as Dread Central points out, Pinhead seems more female — and the character is just a minor subordinate in the Cenobite lineup, rather than the big boss. Barker's original monster also has beautiful jeweled pins in their face rather than rusty nails, and instead of speaking in Doug Bradley's icy baritone, they possess the light, breathy, "voice of an excited girl."

To be clear, Barker directed Hellraiser himself, so he's the one who made these changes. One thing he didn't do, though, was invent the name Pinhead. The writer actually hates that particular sobriquet, as he explained to Grantland, and says it was just a dumb nickname invented by a special effects guy on the set. Oof. When Barker reintroduced a more movie-like Pinhead into his book The Scarlet Gospels, he made a point to rename the character "Hell Priest," and to show him bristling whenever someone called him Pinhead.

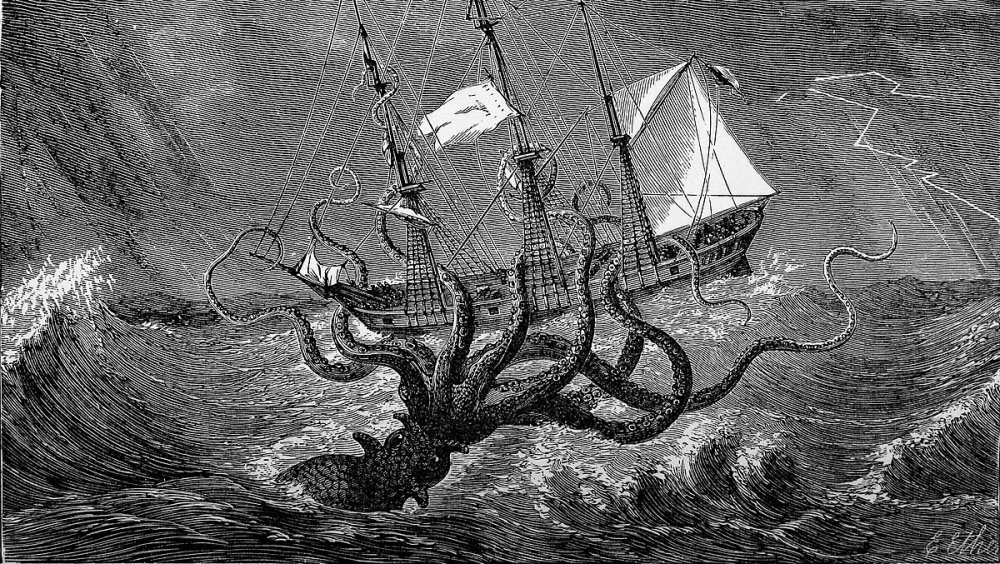

"Release the Kraken!"

... or don't, actually, because the Kraken in Clash of the Titans has nothing in common with the original mythological beast.

See, while "Release the Kraken!" is something that Zeus will repeat in a million memes, forevermore, he never would've said it in any Greek legend, because the fable of Perseus (which Clash of the Titans loosely adapts) features the hero taking down a whale-monster named Cetus. The Kraken, as it happens, originates in Norse mythology. It was a massive, tentacled cephalopod that was believed to drag ships underwater, and Nordic seaman took the beast quite seriously: as pointed out by Film School Rejects, it's now believed that ancient Kraken accounts were probably just exaggerated descriptions of giant squids ... and, admittedly, it'd be scary as hell if one of those suckers wrapped their arms around your wooden boat. Seriously, what do you do, slash at its tentacles with a sword?

This is obviously a far cry from the reptilian, humanoid henchman in Clash of the Titans, invented by stop motion pioneer Ray Harryhausen, which — while an absolute work of art, like so many of Harryhausen's creations — has more in common with a Power Rangers bad guy than the Scandinavian myth it shares a name with. According to the BBC, the closest equivalent to the Kraken that can be found in Greek mythology would probably be Scylla, the six-headed sea goddess with a hunger for humans.

When your plane goes down, blame gremlins

When you hear the word "gremlin," you probably think of a certain 1984 Christmas flick that involves cute little Furby-esque critters which, if you're not careful, will transform into scaly monstrosities. Scary stuff.

That said, the original gremlins were quite different from what Joe Dante, Spielberg, and company would eventually turn them into, according to the Vintage News. During both World Wars, so-called "gremlins" were described by British Air Force pilots as being invisible, humanoid sprites who liked to sabotage planes. Did the engine malfunction? Blame gremlins. Did the wires get cut? Gremlins must've done it, those little bastards. Now, sure, this sounds like a joke, but downed planes aren't funny, and pilots took the threat of these unseen demons quite seriously. Take note that plenty of cultures, all over the world, have also believed in invisible faerie creatures of one sort of another, such as the alleged elves (huldufolk) that are prominent in Iceland, according to the Atlantic.

Anyhow, gremlins made the jump from Air Force legend to popular culture thanks to author Roald Dahl, of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory fame, who was inspired by his own Air Force experiences (and plane crash) to pen a 1943 book called The Gremlins. A few decades later, this work went on to inspire the feature film.

All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy

If you haven't heard, Stephen King absolutely despises Stanley Kubrick's adaptation of The Shining. He really, really hates it. Going over his many reasons could be an article unto itself, but in short, one of his biggest issues is that Jack Nicholson's wild-eyed, scene-chewing depiction of Jack Torrance is like a middle finger to the book version.

The literary Torrance, as explained by Cinema Blend, is framed as a regular man who desperately wants to be a good father and husband, but is struggling against alcoholic tendencies. That's a steep contrast from Kubrick and Nicholson's Torrance, who is, as King told the BBC, "crazy from the jump." In the book, Torrance is quite literally possessed by the spirits of the Overlook Hotel, who are merely using his body as a vessel with which to exterminate his powerful son. Meanwhile, the movie character's descent into psychosis is far more ambiguous — I.E., is the Overlook truly supernatural, or is Jack just a nutcase? — which leaves the impression that even if the spirits are real, they didn't have to do much to push Jack over the edge. After all, this dude spent months writing the same sentence, over and over. Crazy, much?

Basically, while these two Jack Torrance depictions seem similar on a surface level, their inner workings render them as polar opposites.

The Candyman came a long way

Clive Barker is one of the best horror writers of all time, and his monstrous boogeyman "the Candyman" — whether on print or film — is impossible to forget. That said, while the classic 1992 film is highly faithful to the events of Barker's original short story, major liberties were taken when fleshing out the Candyman character himself.

How so? As explained by Birth Movies Death, the original Candyman was depicted as a British white man with jaundice, long stringy hair, and an outfit so goofy that he probably would've elicited laughs in the theater, rather than discomfort. While the Candyman's dialogue and overall M.O. were taken straight from Barker's text, his backstory of being the son of a slave, killed for having an affair with a white woman — I.E., precisely the elements that make the movie character so interesting in the first place — was created for the film, as well as the concept that saying his name five times in the mirror (Candyman, Candyman, Candyman, Candyman ... yeah, stop right there!) was the key that brought him to life. Now, while these alterations are more about filling in the blanks, rather than outright deviations, they do ensure that if the original literary character ever popped up in a film, he would seem unrecognizable, and far less fascinating, than Tony Todd's more developed version.

The basilisk was half-bird, and scared of weasels

What, you think that basilisks are giant snakes? Think again. While the Harry Potter franchise has popularized the notion of these giant serpentine creatures, the creatures that inspired J. K. Rowling's terrifying beast were remarkably different. How so? For one, according to Mythology.net, mythological basilisks were half-bird, half-reptile chimeras, with weird little chicken legs and massive bat-wings that they could flap about on. Gargantuan monsters? Not really, considering they only grew to 12 inches long, at most. The key element that mythological basilisks share with their cinematic counterpart is the fact their gaze can kill a man on sight, a la Medusa, which is definitely their most fearsome quality.

Killer eyesight aside, though, Theoi Greek Mythology writes that mythological basilisks had an Achilles' Heel so dumb it makes Green Lantern's yellow allergy look badass in comparison: basically, if you ever wanted to scare the crap out of a basilisk, you just had to throw a weasel at it. Yes, that kind of weasel. For whatever reason, weasels are immune from the basilisk's death glare, and also produce some kind of "venom" (... uh?) that can kill the little monster. Sure, okay.

From brilliant scientist, to god, to movie monster

Did you know that Imhotep, of The Mummy fame, was a real person? Yeah, seriously. Born in the 27th century, according to Encyclopedia Britannica, Imhotep was basically the Albert Einstein of his day, prized for being one ridiculously smart dude. The official capacity he served under the pharaoh Djoser was that of chief physician, and he was such a boss at healing people that less than a century after his death, the Egyptian people started making up stories about him and worshiping him as the god of medicine.

Hey, good for him. Not so good, though, has been his treatment by Hollywood. While the original "character" of Imhotep in Egyptian legend was a helpful deity, the original 1932 version of The Mummy depicts him as a tragic figure brought back to life by an ancient scroll, as described by the BBC, who lusts after a woman he believes to be the reincarnation of his ancient lover. That's not so bad, but things got even messier by the time the 1999 version of The Mummy rolled around, which rewrites Imhotep as a homicidal priest who murders the pharaoh, is executed for his crimes by being mummified alive — in real life, this would be physically impossible — and then gets resurrected in the 20th century with, you know, supernatural powers. Fun movie, great villain. However, this guy has nothing to do with Imhotep, besides his name and Egyptian heritage.

The Phantom of the Opera is a lot more attractive these days

Back when the 1925 adaptation of The Phantom of the Opera first took off the lead character's mask in one of cinema's first jump scares, revealing Lon Chaney's killer makeup job, it's often said that audiences screamed and fainted.

Since then, though? The Phantom has just gotten sexier and sexier, to the point where he'd be more at home on the shores of Baywatch than a creepy opera house. Much of this is because Gaston Leroux's original book, Le Fantôme de l'Opéra, has been overtaken in the cultural imagination by Andrew Lloyd Webber's Broadway musical, according to Syfy, and most contemporary film adaptations follow suit. While the Phantom of the book is a pitiful, sad figure with the sort of creepy obsession that should get you locked in jail, Webber reimagined the story as an epic romance: this inspired all post-Webber Phantom adaptations to portray the villain as handsome, charming, and deeply sexualized. He was Christian Grey before Christian Grey was a thing. By 2004, when Joel Schumacher was casting the roles of the Phantom and Christine for the latest big-budget film version, the New York Times says that the biggest requirement was for both actors to be young and attractive.

Remember who they cast? That's right, Gerard Butler, whose little eye-mask and dark demeanor can't hide the fact that he's one of Hollywood's biggest heartthrobs.

Rawhead Rex could've been way different

Okay, so Rawhead Rex was a horrendously stupid movie, and a total insult to the Clive Barker story that inspired it. That said, Rawhead Rex's combination of terrible filmmaking — and a toothy ogre monster so dumb-looking that he'll probably appear in memes for years to come — has rendered the 1987 flick a cult classic, to the point where Bloody Disgusting reports that a reboot might be waiting in the wings. Oh, man, talk about a mistake.

Barker's original short story was a complex examination of toxic masculinity and gender norms, as Linda Badley of Middle Tennessee State University explains, but the film went through a prolonged development cycle, which Barker has detailed, resulting in a finished product that is more interested in dumb, gory splatters than any deeper subtext. Perhaps the flick's biggest deviation from the story, though, is seen in the physical appearance of Rawhead Rex himself: as depicted in the text, Rex is supposed to be, quite literally, a 9-foot-tall walking phallus with a mouthful of sharp teeth. No, that's not an exaggeration. Actually, it's the whole point of the story. Bizarre? For sure. X-rated? Oh yeah.

Obviously, the film producers totally missed the point when they reimagined Rex as this fanged Power Rangers creature you now encounter on random Google image searches today. Admittedly, you try pitching a film about a carnivorous sexual organ on the loose, and see if Hollywood answers your calls.

From mythology ... to space!

Like the Kraken, the Ymir is yet another super-cool Ray Harryhausen monster that has nothing in common with the ancient, fantastical, Scandinavian beast that inspired it. In North Mythology, Ymir (pronounced "Ee-mir") is the first living being to exist in all of creation. He's a hermaphroditic frost giant, from whose body all future frost giants come into existence, being spontaneously born out of his legs, the sweat of his armpits (ooookay), and so on. The dynamic trio of Odin, Vili, and Ve all gang up to kill Ymir, and then fashion the universe out of his corpse. Uh, great job?

Needless to say, this tale has little in common with the Ymir depicted in the classic sci-fi flick 20 Million Miles to Earth. Harryhausen's Ymir, as described by Den of Geek, is a space alien from Venus, who goes from cute little critter to monstrous, dinosaurian beast after being tormented by humanity. As the Ymir menaces farmers, military men, and anything else in its path, it keeps sucking up Earth's oxygen, growing bigger and bigger until it eventually gets killed in a fiery conclusion at Rome's Colosseum. Classic movie, and beautiful stop motion work, but why is this thing called Ymir? Who knows, but the original frost giant Ymir probably wouldn't be too happy about it, if his body parts hadn't become humankind's house. Sucks, dude.

Dracula wasn't meant to be a sex symbol

When you hear the name Dracula, you probably picture Bela Lugosi chewing scenery when he's not, you know, chewing necks. Alternatively, your mind might jump to Vlad the Impaler, who called himself Dracula in real life, and probably inspired the name. However, while Lugosi is definitely the best onscreen Dracula and Vlad was a horrifying person, neither of them were anything close to the sort of character Bram Stoker wrote about in his 1897 Gothic horror novel.

See, as the 13th Floor points out, Stoker's Dracula was one nasty dude. Far from the handsome, seductive devil you know, the original character is described as a twisted, elderly monster with a funky mustache, whose breath reeked on account of all that bloodsucking. He had hairy palms, according to Comic Vine, as well as a unibrow, a red mouth with sharp teeth, and ears so pointy they'd make Mr. Spock jealous. Even weirder, Stoker's vampire wasn't allergic to the sun (nor did he sparkle.) He just walked around in broad daylight, like you do. And no, the sympathetic, romantic Dracula that Gary Oldman potrayed in 1992 wasn't accurate, either: between a rap sheet that includes murders, rape, and infanticide, the literary Dracula is thoroughly unlikable.

Looking for a more accurate Dracula depiction? To date, the closest is probably Max Schreck's creepy "Count Orlok" in the classic 1922 silent film Nosferatu.