The Tragic Reason The Moa Bird Went Extinct

So New Zealand is a strange place, right? Highly suitable for hobbits, full of ruggedly gorgeous landscapes largely lacking human civilization (most of the country has nobody living in it), and separated into two main islands cleverly named North Island and South Island. Also: Where did the whole kiwi thing come from? Ah that's right: The nickname for New Zealanders doesn't come from the fruit, it comes from the tiny, flightless bird that lives there. The cute little buggers and their long, thin, bug-pecking beaks and 1-inch-long wings are harmless to humans if only because they run from danger and don't confront it. Plus, they're not big enough to make a decent meal. But what if a kiwi was bigger, brawnier, and made a particularly good target for human hunters? Enter the now-extinct moa.

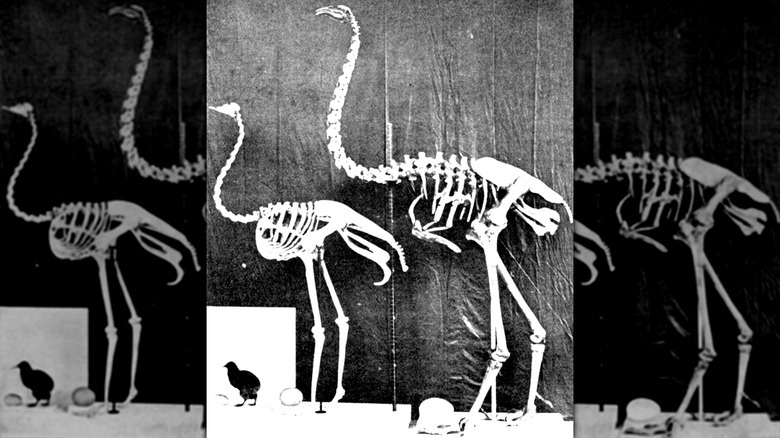

If you want to envision a moa, just think of its close cousins: the emu, ostrich, cassowary, rhea, and other flightless birds. Plus there's that bird that suffered the same fate and has a name now-synonymous with "dumb:" the dodo (which may not be extinct forever). Moas were a type of flightless bird that lived in New Zealand before humans arrived. Lots of walking, not flying, poking around, laying eggs — that type of thing. And then the humans showed up. We're talking the OG New Zealand settlers — Polynesians — who arrived in around 1200 to 1300 C.E.

That's precisely when we start finding archaeological evidence of settlers sinking their teeth into the local, flightless bird population. It took less than 1,500 settlers to decimate the species forever. By the time European sailors arrived in 1642, the moa were long gone.

The sad tale of the moa's demise

In many ways, the tale of the moa is predictable to the point of passé: people are bad and destructive, we indiscriminately abuse natural resources, look at how we nearly annihilated the American bison, etc., etc. But sometimes, things are not so clear-cut. Take the case of the American lion that went extinct some 10,000 years ago. It's tempting to say that some spear-chucking humans obliterated them all, but it's more likely that environmental conditions played a larger role.

The case of the moa is more clear-cut, but it does have some nuance to it. First off: The moa was really, really big. Currently, the ostrich is the world's largest flightless bird at 9 feet tall and over 300 pounds. The moa was about 10 feet tall and up to 550 pounds. That's pretty scary, especially given how mean some modern moa cousins are, like the cassowary. It's scary enough that if you saw a moa, you'd either run or fight. And if you didn't have a Trader Joe's nearby, you'd have to make due with moa stew for dinner.

On that note, Maori tradition — that of New Zealand's remaining Polynesian people — holds that the moa ran quickly and kicked in defense. Their bones got used for hooks, speartips, jewelry, etc., and their meat for food. Before this, the moa evolved in isolation for millions of years and spent its time walking, poking around, and hiding from their only predator, the now-equally-extinct Haast's eagle. But by the end of the 17th century or so, the moa were all gone.

It only took 1,500 people to obliterate the moa

There's one facet of the moa tale that makes it stand out from other stories about humans making animals extinct: How many humans it took to do the job. We can look at the American bison to illustrate — an extreme example to be sure, but one which can help us frame the fate of New Zealand moa. As Ozark Bisons explains, prior to 1800, there were around 60 million bison in North America. By 1840, that number hit about 35.5 million. By 1870, it was 5.5 million, and less than 20 years later in 1889, it was only 541. The year 1872 alone saw 10,000 additional hunters set to the task. They all had guns, some had horses, and they sold bison parts for profit and food.

We don't have nearly as much data about moa. But a 2019 study published in Ecography estimated as many as 2.5 million moa in New Zealand prior to humans arriving on the islands. An earlier 2014 study from the University of Otago and published in Nature Communications found that during the period of highest moa hunting, there were no more than 1,500 Polynesian settlers in New Zealand. That's about one person per 38 square miles, i.e., one the lowest human population densities of any preindustrial society on Earth. It's also 1,666 moa dead per person — and with no guns or horses. Moa hunting also accelerated thanks to the eruption of Mt. Tarawera in 1314. But either way we cut it, that's a brutal end to the moa story.