Things About The American Revolutionary War Your History Class Ignored

American students have learned about the Revolutionary War since the end of the 18th century, though little evidence survives to illustrate just how the founding conflict of the United States was presented to them. What evidence we have indicates a desire to teach the youth of America of the virtues of such founding figures as George Washington, and those books did inspire new generations of American leaders; Abraham Lincoln made a point of citing such a primer as a major influence on him (per The American Revolution Institute).

How the Revolution is taught remains a concern for teachers, historians, and institutions, who all have their own ideas on the right lesson plan. Many of these extol the positive impact of the Revolution on the lives of Americans throughout the ages, and indeed on the world. When education is run through the strong filter of patriotism in American society, it's little surprise that the broad-stroke version of the Revolution most people learn is a positive one. It's more of a surprise that the same general attitude towards the Revolution is found in classes around the world, even in Great Britain.

That's when the Revolution is taught at all in other countries – far from a guarantee. And a starry-eyed view of America's founding conflict can leave a lot out. There are the messed-up things that went on in those days, but also a lot of nuance and color that most of us never find out in school. Here are just a few things likely overlooked by your classroom's study of the American Revolution.

The colonies tried to recruit Canada

Most Americans learn about the divide between the American patriots (or rebels, depending on your perspective) and the loyalists to the mother country. They also learn that British territory in North America was far more extensive than the 13 colonies that later founded the United States. But it's rarely discussed in detail, if at all, why what we now call Canada never joined the U.S.

It wasn't for lack of trying on the part of the 13 colonies. Canada (or more specifically, Quebec) was a substantial colony that dominated the northern border. The rebellious colonists were lobbying their neighbors to join them even before the American Revolution began in earnest. When that didn't work, the Continental Army undertook a short-lived and ultimately embarrassing invasion of Quebec, with written sanction from George Washington himself to "protect" them (per the Smithsonian). Two years later, in a more peaceful effort at enticement, the Continental Congress included a proviso that Canada could join up as a state whenever it wanted without needing a nine-vote majority by the other states.

None of these entreaties succeeded, obviously. The Quebec Act of 1774 had granted the former French territory a significant degree of autonomy, tempering any potential rebellious sentiment there. Quebecois largely wished to avoid a part in the fighting between Britain and the Southern colonies. But the appetite for Quebec didn't entirely leave the Americans, who tried another invasion during the War of 1812. Just as before, short-term success gave way to ultimate failure, and after the conclusion of the war, the U.S. and Canada rapidly moved toward friendly co-existence.

It wasn't just the French helping the colonists

It's sometimes said that the general look at the American Revolution done in most schools skims over the support the 13 colonies had from elsewhere. That's not entirely true; the aid provided by the French is usually given a mention, and if the Marquis de Lafayette isn't a household name on the level of Washington and Jefferson, there is an understanding that he and other Frenchman contributed directly to the American cause.

But the French were not the only foreign powers to support the colonies in rebellion against Britain. Indeed, Smithsonian Magazine has framed the American Revolution as just one theater in a protracted world war between European empires. Spain, France, and the Dutch Republic all had an interest in checking the expansion of British power, prompting them all to offer aide of one sort or another to the colonies. Spain provided arms early in the conflict and later entered a formal agreement with France to support the Revolution. Dutch merchants, without official sanction from their government, ran supplies and arms.

As the Revolution went on, Britain was increasingly tempted to spend its resources on other imperial conquests rather than try and hold onto 13 colonies. A series of peace agreements saw America, Britain, Spain, and France all come away with something they prized (the Dutch found themselves worse off for the conflict). That the Revolution was part of a broader international war was a recognized and acknowledged fact for the Founding Fathers. It was only over the course of the 19th century that American accounts began neglecting the role played by its allies.

The Boston Tea Party wasn't a tax protest

A quick summary of any historical period is going to simplify things, sometimes to the point where the substance of events can get lost. Such is the case of the Boston Tea Party, among the more famous but misunderstood episodes in the lead-up to the American Revolution. It's often conflated with the general protesting of "taxation without representation," but as editor Joseph J. Thorndike explained in Forbes, the Tea Act of 1773 that sparked the Tea Party was technically a tax cut, not a tax hike.

But the tax cut was designed to protect the bottom line of the British East India Company, sometimes estimated to be the most powerful corporation in history. By cutting taxes on company tea, the British government allowed them to undercut the prices offered by merchants and smugglers who had long brought untaxed tea into the colonies. And colonists saw in this move an attempt to impose a monopoly that could ruin them, leave them more dependent on Britain, and undercut the protests against a lack of representation.

Organized protests in several colonies persuaded merchants to send EIC ships back to the mother country without having unloaded their controversial tea. It was hoped by the likes of Samuel Adams that the same could happen in Massachusetts. But the colonial governor, Thomas Hutchinson, would not permit the ships to leave, and Adams told an assembly that there was no prospect of changing his mind. Shortly after, the Tea Party broke out, with thousands of onlookers taking in the sight of their fellow Bostonians tossing the tea into the harbor.

The American economy was in tatters after the Revolution

Wars are costly things, in both blood and treasure. The American Revolution won the 13 colonies their freedom — but at a heavy price. To pay for the war, the Continental Congress printed more money, which eventually resulted in hyperinflation, and took out loans with its French and Dutch allies. Because the Articles of Confederation established after the Revolution did not empower Congress with sufficient authority to collect taxes, repaying those debts became increasingly difficult.

The debt was borne by both the federal and state governments, and the currency of the young republic had no backing and little sustained value. And trade, particularly with Britain, collapsed immediately after the war. All these factors combined to send the United States into a severe economic depression in the 1780s, one so severe that it's been compared to the Great Depression (per the American Battlefield Trust).

Rather than cooperate in the face of economic hardship, the states competed with one another for advantage. Early efforts to resolve the situation in the 1780s went nowhere. Soldiers who had fought for the republic were often left with unpaid wages due to the depression and debt crisis. Things came to a head in 1786 with an armed uprising led by former captain Daniel Shays. While short-lived, Shay's Rebellion helped create the Constitution by making unavoidable the dire economic straits of the U.S. and the inability of the government under the Articles of Confederation to deal with it.

The Declaration of Independence wasn't signed on July 4 (or 2)

John Adams always felt that the day of celebration commemorating American independence should be July 2, not the 4th. After all, the 2nd was the day that the Continental Congress formally voted to adopt a resolution of independence in 1776 (per the National Constitution Center). But the Declaration of Independence was only approved two days later, and it was the adoption of that document that cemented the commitment to liberty in the minds of many Americans, Adams's fellow founders included. And so the 4th of July became fixed as Independence Day by the early 19th century (a development helped, in part, by Declaration author Thomas Jefferson and his Republicans becoming the predominant force in American political life by then).

If we're splitting hairs, though, we must acknowledge that many Americans assume the Declaration was signed on July 4, 1776. But the version of the Declaration that went to the printers that July had only one name at the bottom: John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress. Other members of the congress only began signing an engrossed copy that August.

By that time, the makeup of the congress had changed. Not everyone who signed the Declaration as part of their state delegation had been present for the debate leading up to the independence of the vote to seek it. Even if the signing had happened on the 4th, several delegates were absent and New York abstained from voting. It was only in January 1777 that a copy of the Declaration was published with the full list of signatories included.

The American Revolution was part of a wave of rebellions

The larger war between European powers factored heavily in the decisions of Spain, France, and the Dutch Republic to support the American Revolution. But just as the Revolution was one part of that larger war, it also represents a link in a chain of revolutions that swept across the world at the end of the 18th century and continued well into the 19th. Indeed, the American Revolution impacted the French Revolution to a remarkable degree and even contributed to it in how much it increased the debts of France under Louis XVI. Another ally, Spain, lost its American empire in a wave of wars of independence fought in Mexico, Chile, Argentina, and beyond.

American influence was also evident in the successful Haitian Revolution (though the United States took until the Civil War to recognize Haiti as a nation) and the unsuccessful Irish rebellion of 1798. Brazil broke away from Portugal. And Greece, the homeland of so many ideas that inspired the Founding Fathers, won its independence from the Ottoman Empire after the American Revolution.

Those ideas from ancient Greece were part of the stew that was the Age of Enlightenment, a long period of profound philosophical and intellectual development. Its roots have been traced to the restoration of the monarchy in England after their civil war (per American Battlefield Trust) and it birthed a hefty system of thought supporting ideas of liberty, constitutional government, and the progress of humanity. The American Revolution and its successors, however imperfectly, strove to embody those ideals.

There were monarchists even among the rebels

That there was a divide between American colonists who sought independence and those who wished to remain part of the British Empire should be obvious, and it's a well-covered fact in most school curriculums on the American Revolution. But in that neat and simple division, one might get the impression that monarchism was only found among the loyalists. While democratic practice was not new to the colonies (or to Britons) by the time of the American Revolution, it was far from guaranteed that the United States could sustain a republic — or that everyone who fought for independence wanted one.

A number of soldiers serving in the Continental Army wanted to establish an American constitutional monarchy, with an American-born monarch. Per The Collector, one even wrote to George Washington in 1782 encouraging the general to make himself king. Even after Washington firmly refused, the dream of an American monarchy didn't die. Tempted by "enlightened despotism," a group led by Continental Congress president Nathan Gorham approached Henry of Prussia about becoming a king.

Henry declined just as Washington had, reasoning that a people who had just fought for independence from one king wouldn't be keen on another (though he did suggest they ask the French instead). And the Constitutional Convention never considered a monarch by name. But Alexander Hamilton still floated the idea of presidents that served for life, a trapping of monarchial power that his fellow delegates ultimately shot down.

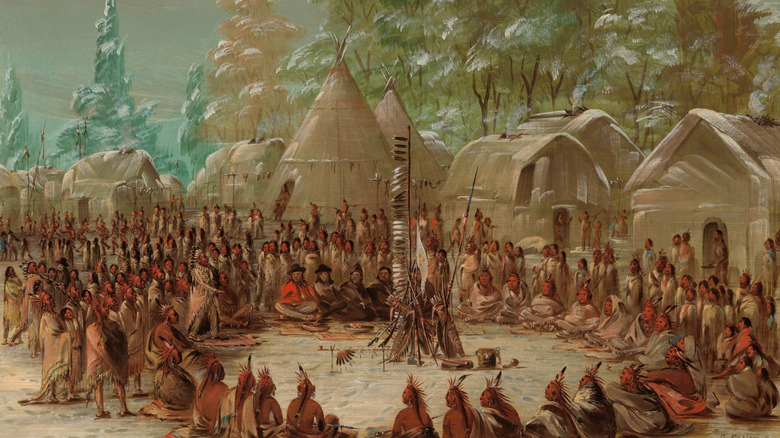

Native American allegiances were divided

If the nuances of the British and colonial positions in the American Revolution are often sanded away in quick recounts of history, the position and feelings of Native American groups can get left out altogether. The closest many lesson plans come to touching on Native involvement is explaining how the French and Indian War impacted the American Revolution. But Natives were an active force in the conflict on both sides.

Before the Revolution began, the British government had tried to keep the Natives and colonists separated to deter any fighting. The large tracts of land reserved for the Natives in the West were a sore spot for many Americans, and when the Revolution broke out, it was widely assumed that the Natives would side with the redcoats. But according to the American Battlefield Trust, most tribes sought neutrality at first. A few Natives did join the rebels at Boston in 1775, but only gradually did most Native nations become involved.

While the British could point to their land policies to entice allies (and indeed, many Natives saw an America without those treaties as the greater threat), the decision of who to fight for wasn't an easy one, and it caused several fractures within Native communities. The Iroquois League, whose members had cooperated for centuries, split over the issue, as did the Cherokee Nation. Natives on both sides acted as scouts, foragers, and fighters. But whichever side they chose, the Natives lost heavily in the aftermath due to the British surrender of all the Western territory they once kept the colonists from settling at the Natives' expense.

The Revolution didn't end at Yorktown

Schoolbooks, popular history accounts, and "School House Rock" all pin down the end of the American Revolution to the Battle of Yorktown. And it is broadly true that Yorktown led to the end of the Revolution. Following the battle, the British had no sizable or sustainable force to fight within the colonies. But the surrender of General Charles Cornwallis to George Washington was not the final word on the fighting for American independence.

Per Marc Liebman, Cornwallis surrendered in October 1781. Serious peace negotiations between the Americans and the British didn't begin until April 1782, and it took well over a year to draw up and sign the Treaty of Paris. At that time, fighting continued on the seas and deep in the frontier of British-American territory. French and British ships traded fire, French forces attacked British Canada, and skirmishes between Native Americans, American loyalists, and colonial soldiers raged throughout the West. 1782 would later be dubbed the "Bloody Year" for the intensity of the fighting that went on in unsettled territories (per the American Battlefield Trust).

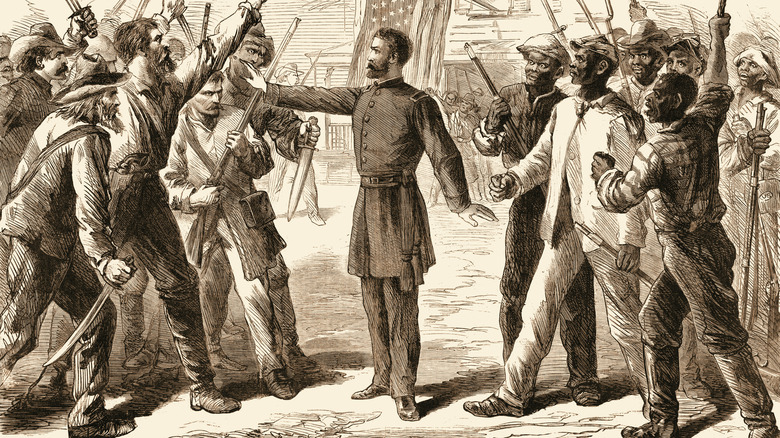

Some Black Americans fought for the rebels

Slavery has always been the biggest dark cloud hovering over America's founding. The white leaders of the American Revolution were well aware of the contradiction that slavery presented for a movement and a nation founded on ideals of liberty and equality. The hypocrisy didn't escape British notice either. A royal proclamation promising freedom to any Black American who fled their masters and fought with the redcoats attracted some 100,000 people according to the National Park Service.

But some Black Americans chose to fight with the colonial rebels. As early as the Battle of Lexington, there were Black combatants on the side of the colonists. At first, some Black Americans held out hope that the vision of America being espoused by the founders would mean their freedom. Even when that proved otherwise, between 5,000 and 8,000 African Americans participated in the Revolution in some capacity.

To let them do so was a bitter pill for many of their white leaders. There was a real fear of arming slaves, even for the sake of independence, and the racism prevalent at the time left many in the Continental Army doubtful of the abilities of Black soldiers. But as the war went on and colonial manpower became strained, they had no choice but to accept Black men into the army and navy. And many served with distinction and won their freedom by the war's end.