Empresses And Emperors Who Were Really Weird People

Sure, being king or queen of something would probably be pretty cool, but there's one final upgrade even for those crowned heads: being an emperor. As the only people to outrank and occasionally boss around kings and queens, emperors and empresses are at the absolute pinnacle of the inherited-or-seized power pyramid. And as you might imagine, being at the top of the totem pole can mean there's no one around to calm down, contradict, or otherwise prevent these rulers from doing whatever they please, even when it's imprudent, evil, or bizarre.

Some imperial officeholders inherit their roles, making them subject to the same inbreeding and separation from the real world that has turned other royals into pretty bizarre people. Others seize power by force, declaring themselves emperor when they see an opening at the top of the heap, and the kind of person who decides they can be an emperor on their own say-so tends not to be a chill, easy-going people-pleaser. Some of the strangest behavior in recorded history has come from the thrones of empires — often with terrible results.

Elizabeth of Russia

Pretty and charming Elizabeth of Russia had, as a daughter of Peter the Great, initially been skipped over for the crown. By 1740, the nominal czar was the infant Ivan VI, and his mother made the mistake of threatening to pack fun-loving Elizabeth off to a convent. Elizabeth, who hadn't tried to become empress before, was popular with the royal guards, and so she booted little Ivan off the throne and took it for herself.

Elizabeth valued family as an abstract concept but was sharp-tongued and domineering with her own. She may have secretly married a handsome peasant with a beautiful singing voice, but she never publicly married as empress. Instead, she brought her sniveling little nephew in from a German backwater, made him her heir, and married him to a minor German princess. When this princess, who would eventually be Catherine the Great, gave birth, Elizabeth took the child away to raise herself.

Elizabeth was not terribly interested in actually running Russia, so she let her government do the work while she partied. Tall and attractive, she looked good in men's clothing, so she threw regular "metamorphosis balls" at which attendees were required to cross-dress. She looked striking in menswear, and everyone else looked uncomfortable in bad drag. Once, when a hairdo went awry, her head had to be shaved: Unwilling to be a good sport about it, she made all her female attendants shave their heads in forced solidarity.

Elisabeth of Austria

Elisabeth, empress of Austria (and queen of Hungary), provides an example that wealth and beauty cannot guarantee happiness. Strikingly beautiful when she married the young emperor of Austria in 1854 and loved by her husband and her people (particularly in Hungary, which she especially favored), she was stalked by tragedy and unhappiness until her senseless assassination in 1898.

Elisabeth was so vain that, after the age of 30, she simply refused to be photographed. (She wasn't painted after 40.) Also at 30, she proclaimed herself finished with childbearing. She'd produced three children, including a male heir, and that would have to be good enough. This left her without a clear role in the court at Vienna: She did not have a pet charity, a political role, a compatible relationship with her husband (though they reportedly did love one another), or a personality that would let her sit around in pleasant rooms and mark time, so she spent her life in nervous activity.

Elisabeth exercised obsessively to maintain her slimness and slept wrapped in beefsteaks, intended to help preserve her skin. She had her maids spend hours on her hair, so much that she had time to take Greek lessons while they worked. She wrote a surprising amount of poetry, with instructions that it was not to be read until the 1950s. Among her time-filling activities was frequent, restless travel, which is why she was in Geneva when an anarchist assassin, deprived by chance of his first target, fatally stabbed her.

Julian the Apostate

Julian the Apostate was, very briefly, one of the luckiest men to ever become Roman emperor. In A.D. 360, he was with an army in Paris, resting after a successful war against Germanic tribes, when his troops responded to a proposed reorganization by proclaiming him emperor — which meant war with the existing emperor, Constantius. Before this was could really kick off, however, Constantius died, naming Julian his heir on his deathbed.

Julian was very interested in presenting himself as a philosopher, even growing a then-unfashionable beard so he'd look more like a Greek thinker than a Roman ruler. Now that Julian was emperor, he could pursue a personal project: rolling back Christianity, which he considered too young a religion to take seriously. He personally sacrificed animals and had Christians kicked out of the army and certain academic positions, all while trying to issue religious commands as a sort of pagan pope. He attempted to order the rebuilding of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem (expressly to annoy Christians), and in various important Christian churches, he added statues of Bacchus, god of wine and general fun.

Unfortunately for Julian, his fellow pagans, and the empire, none of this was especially good preparation for war with Persia, which was the kind of thing Roman emperors needed to be ready for. After a successful initial invasion, Julian's force met ferocious resistance, and the last non-Christian emperor of Rome took a fatal spear to the gut.

Wilhelm II of Germany

When Wilhelm II came to the German throne in 1888, he was 29 years old and already a fairly unpleasant man. He was Prussian in every negative sense of the word: bullying, fussy, self-important, and nationalistic. His left arm had been paralyzed during a traumatic birth, and while it's tempting to place self-consciousness about this disability at the root of Wilhelm's difficult personality, it's also too neat and condescending an answer.

Impulsive and short-sighted, Wilhelm was not a very good ruler. He let an alliance with Russia lapse, allowing it to make the partnership with France that would ultimately prove so unhappy for Germany during World War I. He almost started wars several times before World War I due to his erratic behavior, doing things like publicly congratulating South Africa for defeating a British raid (to British annoyance). In 1904, he went to Tangier and tried to undermine French control of Morocco. In 1908, he caused a diplomatic crisis by giving a newspaper interview in which he referred to the British as "mad as March hares" and hinted that Germany's naval buildup was directed at Japan or China.

When the big war did finally arrive in 1914, Wilhelm was the figurehead of the Central Powers but had no real authority to shape the war beyond bluster and bellicose rhetoric. He lost his throne at the end of the war and retired to the Netherlands, where he lived as a private citizen until his death in 1941.

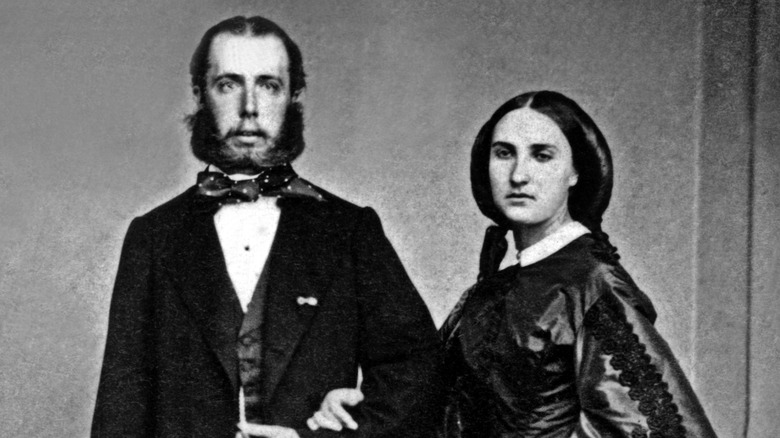

Maximilian and Charlotte of Mexico

In 1861, France, annoyed at late foreign debt repayments, invaded Mexico with the plan to create a pliable client state. This new Empire of Mexico was to be headed by a spare European prince, Maximilian of Habsburg, and his wife, Charlotte of Belgium. The royal couple had a difficult hand to play, and they played it like weirdos.

Mexico, it turned out, didn't want a European ruler, and the civil war France had interrupted continued against Maximilian's government. Maximilian also didn't really want to rule and was more interested in butterflies and women, but he'd made a commitment. Since he had no children of his own, Maximilian snatched the grandchild of Mexico's former emperor, Agustin I, who had ruled briefly after Mexican independence, to present as his heir. For good measure, he exiled the child's family. None of this really endeared Maximilian to anyone, and he was overthrown and shot, with his final request being that the shooters avoid hitting his face. (The child grew up to be a college professor in the United States.)

Charlotte, when she saw how bad the situation in Mexico was, had gone back to Europe to seek help for the teetering imperial government. She was so dogged in asking for help from the pope that she became the only woman recorded to have spent the night in the Vatican, but she spent her interview with the pontiff trying to spit out poison she thought she'd been given. After she learned of her husband's death, her nerves gave way completely, and she spent the rest of her life in seclusion next to a doll dressed as her late husband.

Hirohito of Japan

Hirohito, emperor of Japan during World War II, is strange less for his personal qualities than for the very odd position in which he found himself. According to Japan's ancient traditions, he and his family were descendants of the sun goddess Amaterasu, but he himself was a timid man, interested in marine biology, who only rarely made use of the authority he had as emperor.

Scholars disagree over how much Hirohito participated in the development of Japan's wartime strategies, but it is likely that he at least knew of some of the atrocities carried out by the Japanese armed forces. He did not make any recorded attempt to intervene to stop them until the very end of the war, when he gave a public radio address announcing the surrender to the Japanese public without using the word "surrender." This speech, in formal, flowery court Japanese, became known somewhat over-excitedly as the Jewel Voice Broadcast.

The next year, Hirohito gave another radio address in which, as per the terms of the surrender, he renounced his claim to divinity, making Hirohito one of the very few people in human history to assert positively that they are not kind of a god. He kept his throne and began to travel around Japan and, ultimately, the world, becoming the first sitting emperor to leave Japan. He visited Europe and the United States, where he went to Disneyland and met Richard Nixon — a strange comedown for the sun's great-grandson.

Commodus

Most people list Marcus Aurelius as one of the most successful Roman emperors, but he made an important stumble right at the end: He named his vain and violent doofus of a son Commodus his heir. Marcus Aurelius had provided his son with tutors and firsthand military experience to prepare him for rule, but he had either failed to notice or had disregarded the seeds of a disordered and dangerous personality.

Commodus was physically strong, and so he admired the mythic figure Hercules. So far, so good, but he began to dress as Hercules, complete with lion skin, and stage fights in the arena starring himself, allowing him to reenact his hero's victories while killing exotic animals and costumed human beings. At some point, he seems to have identified himself so intensely with Hercules that he forgot that he wasn't really the legendary strongman. He even had a colossus styled after Nero refurbished to look like Commodus-as-Hercules as part of a program of placing statues of himself around the city, and minted coins with the name "Hercules Commodianus."

Commodus' love for himself even led to his trying to rename Rome "Colonia Commodiana." His violent nature ultimately so unnerved his mistress and most important servants that they poisoned him before he could kill them. When the poison didn't work, they sent in a muscular athlete to strangle the drowsy emperor.

Czar Ferdinand I of Bulgaria

When a game of musical thrones left Bulgaria without a ruling prince, the interested parties, after failing to attract their first few choices, settled on a Viennese-born princeling named Ferdinand to warm the empty seat. Marginally better than nothing, this man would outfit Bulgaria with an internal secret police network before upgrading himself to czar in 1908, falling off his horse during his own coronation procession.

The flagging Ottoman Empire was easy pickings by the 1910s, and Ferdinand organized an alliance of interested states to divvy up its remaining European possessions. This plan worked in that the Ottomans lost territory, but the division of goodies was so mismanaged that Bulgaria walked away with a pittance. Ferdinand and Bulgaria were so mad they threw in with their old enemies the Ottomans as one of the Central Powers during World War I, which ended with Bulgaria defeated and Ferdinand deposed.

Bisexual and promiscuous, Ferdinand did not take sufficient trouble to conceal these behaviors that were taboo in conservative Bulgaria. Ferdinand was so reviled among the Western allies that an entire book about him was written with the subtitle "The Amazing Career of a Shoddy Czar." It describes a tragically vain man, proud of his beard, embarrassed of his large nose, and with an entire rehearsed spiel he gave to try to charm visiting journalists, complete with props like the keys to the palace and a stuffed game bird he had shot.

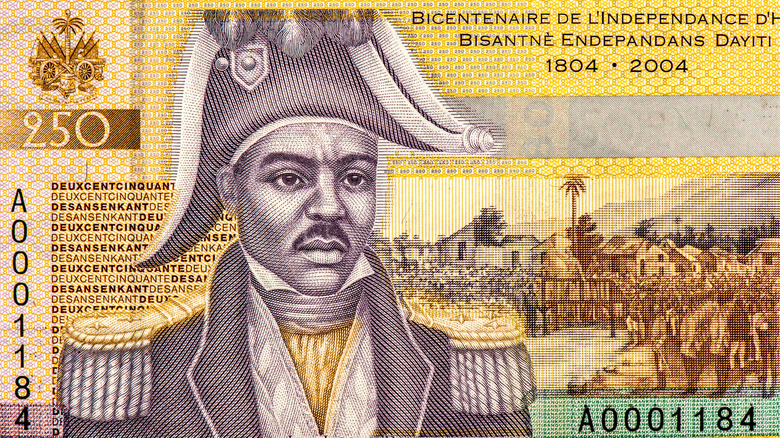

Jacques I of Haiti

On January 1, 1804, Jean-Jacques Dessalines proclaimed the independence of Haiti. The enslaved population of the island had been in revolt since 1791, and with this proclamation, they cast off French control and prepared to move forward as free people in a free country. Unfortunately, Dessalines was at the head of that movement.

Born into slavery, Dessalines had been an excellent commander during the war, but his personal ambitions exceeded those he had for the people of Haiti. In September of 1804, he declared himself Jean-Jacques I, Emperor of Haiti. Now under a local monarch instead of a far-away one, Haitians were in for a miserable two-year reign. Jean-Jacques had thousands of the island's white population killed to avoid the possibility of a reinstatement of the previous racial hierarchy or any local support for a French return. White men were not allowed to own property unless they were Polish or German. As for the formerly enslaved Black Haitians, they were subjected to a ... system of forced labor, designed to keep the island's plantations functioning and the economy from collapsing back into subsistence farming. This was not the liberation of which they had dreamed.

Emperor Jean-Jacques was deposed and killed in 1806. For all his failings as an emperor, he's been given one of the few higher honors after his passing: Some practitioners of Haitian Vodou revere him as a loa, a spirit sent by God.

Anna of Courland, Empress of Russia

When the Russian throne fell vacant in 1730, the court looked next door. Peter the Great's niece Anna had been running the Duchy of Courland (now very roughly Latvia) since 1711, when her husband had died shortly after their marriage. Politics had prevented her remarriage, and the duchess had become a strange woman, bitter, only semi-literate, and ill-mannered. The Russian nobles sent Anna an offer of the throne along with a list of conditions she would have to abide by if she accepted. She arrived in Russia, took the throne, and after some political maneuvering, tore the conditions up with her own hands. After this point, Anna ruled as an absolute monarch, prioritizing the security of her throne and her personal authority.

This meant extending her reach into the personal lives of aristocrats and courtiers to display her control, including arranging marriages when she liked. The most dramatic example is the infamous ice palace wedding, when she forced her court jester, a "disgraced" noble who had annoyed the empress by having been happily married to a now-dead Roman Catholic, to marry an elderly woman from the Kalmyk ethnic group, a minority group descended from the Mongols. The bride, groom, and their unfortunate guests endured a ceremony and an overnight stay in a palace made of blocks of ice, with ice furniture, guarded to make sure none of them slipped out to warm up during the night. Fortunately, Anna's event-planning career ended with her death the following year.

Bokassa I of the Central African Empire

Shortly after the Central African Republic became independent from France in 1960, its new president, David Dacko, tapped Jean-Bédel Bokassa to leave the French army, in which he had served with distinction, to lead the new Central African armed services. Bokassa agreed, then overthrew Dacko to become president in 1965. In 1976, he decided he was now the emperor of the rebranded Central African Empire, due to an alleged descent from Egyptian pharaohs.

The next year, Bokassa the First (and so far, only), was crowned in an obscenely lavish and bizarre celebration that cost about $45 million, roughly the Central African annual budget. Bokassa had, at least, gotten the French government to pay for it. Though Bokassa was Muslim, he asked the pope to crown him, and consulted the Greek ambassador to Cameroon about Byzantine court etiquette. The event itself took place in a Yugoslav-built basketball arena, and Bokassa wore a Roman toga covered in tens of thousands of pearls and sat on an enormous gold throne shaped like an eagle, intended to reference Napoleon.

The empire, such as it was, lasted about three years. Bokassa was good at pageantry but bad at running a country, and after reports of mismanagement and violence against civilians piled up, the French helped reinstall Dacko. Bokassa was sentenced to death while in exile (though acquitted of cannibalism charges) but returned to the Central African Republic anyway some years later. He spent a mere six years in prison, dying a free man in 1996.