The True Tale Of The Green Knight

Audiences have listened, captivated, to the tales of King Arthur and his knights for centuries, and it's no wonder. The stories are filled with everything you could possibly want: there's the knights and their chivalric values, of course, but there's also mystery and intrigue, illicit affairs, supernatural creatures, and the search search for not just the Holy Grail, but for the self, for meaning, and for purpose. In other words, it's partially what we want to dream of, and partially something we can definitely relate to.

Arthur, Lancelot, and Guinevere are all familiar names, but the main character of David Lowery's 2020 film The Green Knight is probably less familiar. Dev Patel stars as Sir Gawain, and no, he's not the Green Knight of the film's name. He is, however, one of the core knights who has been around since the earliest of medieval legends, and the story the film is based on is more properly called Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. It was written around 1400, and according to The British Library, it's still considered one of the most important works of English literature, and one of the best works of Middle English poetry ever written. Even better? It's a great adventure.

Haven't read it? It's massively difficult in its original form, so let's give you a primer on the basic story. (While it's not clear how true to the text the film will be, there are definitely some major spoilers in here.)

Who is the knight at the center of the tale?

It's worth taking a moment to look at the history behind Dev Patel's character, Sir Gawain. He's not one most would recognize from movies alone — Liam Neeson portrayed him as a drunken lout in 1981's Excalibur, and even in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, he gets just a brief mention before he's reduced to rabbit food. In the actual Arthurian legends, though, he's incredibly important.

Go back to the legends from the Middle Ages, and you'll find Gawain appears more often than knights — like Lancelot and Galahad — who are more widely recognized today. He's the son of King Lot, ruler of Orkney (in Scotland) and Morgause (sometimes named Anna in early versions). And that's important — she's Arthur's sister, which makes Gawain his nephew. Since he shows up in so many works, The Camelot Project notes that it's not surprising that he's rarely the same person. He does have some defining characteristics, though: he's one of Arthur's most trusted companions, he's usually a very relatable everyman, and he often finishes quests that other knights have failed. Most tales have a certain chivalric quality at the center of them, and whether it's honor, compassion, wisdom, or something else, he's often one of the most noble.

In early tales, that is. In more modern works, he's devolved into a drunken, bloodthirsty, murdering oathbreaker... not precisely the knight you expect, but originally? He wasn't like that at all.

A holiday beheading challenge set by the Green Knight

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight starts just after the beginning of the new year, when Camelot is still a bustling hub of holiday festivities. There's carols and tournaments, jousting and feasting, and plenty of storytelling. It's in the middle of one of those feasts that the doors swing open and a massive figure rides in. He's no ordinary knight, though: he's entirely green, from his clothes to his beard. His horse, too, is entirely green, and his appearance stuns everyone into silence. He carried a spring of holly in one hand and an ax in the other, and demands to speak to Camelot's lord.

He'd heard tell of the valiant knights who lived at Camelot, and he came with a challenge: prove their worth with a fun Yuletide game. He'd hand over his ax, and give one man a single swing at him. In exchange, a year and a day later, the Green Knight would return the blow. At first, no one volunteers. When Arthur steps forward, it's Gawain who interrupts and asks to be the one to take the challenge. Arthur waves him forward, Gawain takes the ax, and with one blow, he beheads the knight.

But the Green Knight reaches out and catches his head, remounting his horse and — turning the head to face the court — reminds Gawain of his promise. He has a year and a day to meet his fate at the Green Chapel. The monstrous knight rides off, and amidst some rather nervous laughter, the feasting resumes.

Setting off to find the Green Knight's chapel

A year passes, and on that All Hallows' Day — November 1 — Gawain is still at Camelot. He's preparing to leave, though; he says his goodbyes, other knights gather to bid him farewell, and to mourn just a bit. They lament the inevitable loss of this good and courageous man, even as he puts on his armor, saddles his faithful horse, Gringalet, and sets off in search of the Green Chapel and his appointment with what's surely certain death.

And here's where the story skips over a lot. It describes "peril and pain, and many a hardship," but just what happens to Gawain on his journey isn't exactly clear. The text hints that he rode and rode, searching for the Green Chapel, and not finding it. Along the way, though, he fought and faced dragons, wolves, wild men, boars, bears, and bulls, and even a group of giants. It's a story the reader doesn't entirely get — but wants! — and why? Because none of that was the worst that he faced: worse than any combat was the knowledge of what's waiting at the end of his journey, and worse still, there's the cold, the rain, and the ice. He spends what he believes are his last weeks in the world cold and alone, save for the company of his horse, and he's left to ponder his inevitable fate.

A Christmas miracle

From the earliest tales of King Arthur and his knights, faith is a recurring theme. Gawain has been riding for almost two months, and it's Christmas Eve. Alone, cold, and troubled, he says a prayer and asks to be guided to a place where he might find some shelter, and where he might hear Christmas Mass, and pray to those he holds most sacred.

His prayer is answered, and he almost immediately comes upon a moat surrounding a hill, and a castle that towered above them. He rides to the castle and calls out — a porter tells him that he's welcome to stay as long as he likes, and he's brought before the lord of the keep, who displays all the courtly virtues of hospitality and kindness toward this weary stranger. He's described as "one well fitted to be a leader of valiant men," and he gives Gawain fresh, dry clothes, and treats him to a feast. Gawain, in turn, tells stories of Arthur's court, and it's decided he'll stay through Christmas.

It's only after the feast that he meets the ladies of the castle: one — the wife of the lord — is young and fair, more beautiful even than Guinevere. The other is old and wrinkled, sickly-looking, even. They celebrate Christmas, and even as the lord bids him to stay, he says he can't. He's looking for the Green Chapel and for the first time, he's found someone who knows where it is — just a few miles away.

The knight's test

More times passes, and soon, it's only three days until Gawain needs to head to the Green Chapel and fulfill his end of the deadly deal. He's in a hurry to just get moving and get it over with, but his host assures him that the chapel is just a short ride away. He promises him that he can spend those three days at the castle, resting and recovering from his already long journey, and preparing for the trials that lay ahead. To pass the time, and make things a little more interesting, he proposes a little friendly wager.

He's going to go out hunting with his men, while the lady of the castle keeps Gawain company for the day. Whatever the host and his men manage to bring back from their hunt will be Gawain's, his host promises — on one condition. Whatever comes into Gawain's possession while he's at the castle, he has to give the host. They good-naturedly agree, seal the deal over a cup of wine, and retire for the night.

The exchange

Things start out pretty uncomfortably for Gawain — he's woken the next morning when his host's wife slips into his room while he's still asleep. He very, very diplomatically tells her that he's not offering what she wants, and spends the entire morning trying not to insult her while continuously turning down her advances. She ultimately leaves, but not before she kisses him once. The lord returns, offers Gawain the spoils of the hunt, and in return, Gawain kisses him — but refuses to tell him where the kiss came from, as that wasn't part of the deal. They laugh, and all is well.

On the second day, the same thing happens — and Gawain escapes with nothing more than a kiss. Again, he shares in the hunt, and again, he kisses his host.

The third morning plays out a little differently. The lady comes into his room again, but this time, she mourns the fact that she'll never see him again, and asks to give him a token of her affection. He refuses, saying he has nothing to give her in return, and that the ring she offers is too costly. Instead, she gives him a girdle — or belt — of braided green silk. It's not costly, she says, and more importantly, it's magic: anyone who wears it couldn't be killed. He considers, briefly, then accepts the belt. When the host returns, he doesn't hand it over, as was the agreement.

Keeping the promise to the Green Knight

The next morning, Gawain dresses, takes the belt, and leaves the castle with a guide. The guide takes him fairly close to the chapel, and warns him of the nature of the man who waited for him. The Green Knight was merciless and discourteous, taller, stronger, and more powerful than any other man, and would not hesitate to kill. Gawain was certainly riding to his death, and if he bailed now, no one would ever find out about it from the guide.

Gawain refuses, and continues on to the Green Chapel — where, of course, the knight is waiting for him, ax in hand. As Gawain removes his helm and kneels, the Green Knight delivers three blows: the first two do nothing, and the third cuts his neck a bit.

Gawain gets up, incensed. He kept his end of the bargain, returned, and faced the blow without flinching ... so he's not happy there were three. Then, he finds out that the first two were feints, delivered by the Green Knight because Gawain had been honest about the kisses received from his host's wife. The third cut him... because he had lied, and not surrendered the belt. As the Green Knight explains, Gawain realizes that he isn't just talking to the Green Knight — he's talking to the host who had welcomed him into the castle, and who he'd made another bargain with... a bargain he hadn't upheld, because he had been more concerned about his life than his honesty.

The one who was behind it all

The Green Knight/host's name is Bernlak de Hautdesert, and he explains just what kind of magic is going on. The old lady from his castle wasn't any old woman, it was Morgan le Fay — Arthur's half-sister, Gawain's aunt, and a figure who exists in the tales in constant opposition to the courtly values of Arthur and his knights. She had approached the lord of the castle and enchanted him, bidding him to go to Camelot for a few reasons: she wanted to terrify Guinevere with the sight of the giant knight picking his head up off the floor, hoping her fear would kill her. She also wanted to prove that the Knights of the Round Table weren't as valiant as all the stories said, too, and as far as the Green Knight was concerned, Gawain had proved her wrong. Mostly.

He invites Gawain back to the castle and unsurprisingly, he declines. Instead, he sets off for Camelot, and has plenty of other adventures on the way that again, aren't mentioned with any detail. When he gets back, he's still carrying a heavy dose of shame with him: he had valued his life over his honesty, and it haunted him. He swore to always wear the belt as a reminder of his weakness and, in solidarity, all the other knights promised to wear a similar green belt in honor of his bravery.

No one knows who wrote 'Sir Gawain and the Green Knight'

According to The British Library, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight — along with the other works by the same author — are among the most important of the Middle Ages. And here's the thing: no one has the foggiest idea who wrote them. In fact, we hardly know anything at all about the author. Historians and scholars have determined that the work was probably first penned at some point in the late 14th century, and it was written down and illustrated at the beginning of the 15th. The dialect has allowed them to pinpoint where the poet was from: the Midlands.

He's known as The Pearl Poet, and the name comes from one of the other stories in the same manuscript. It's a massively complicated tale, and it's basically the story of a father who has just lost his daughter. Overcome with grief, he falls asleep, and has a vision of her — as a young woman — in heaven, where he speaks to her and attempts to reconcile his loss with her new place alongside Christ.

There's also Cleanness (or Purity), which retells the parables of Noah's flood, the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, and the fate of Belshazzar and David within the framework of spiritual purity, and Patience, which uses a retelling of Jonah to illustrate the importance of enduring suffering, and the knowledge that God will do all in His own time.

The original Green Knight manuscript is absolutely incredible

It's something of a miracle that the Pearl Poet's stories were preserved at all, as there is only a single copy remaining from the era. It's in The British Library now, and it's kept not just under lock and key, but in a carefully-controlled climate to help preserve the delicate text.

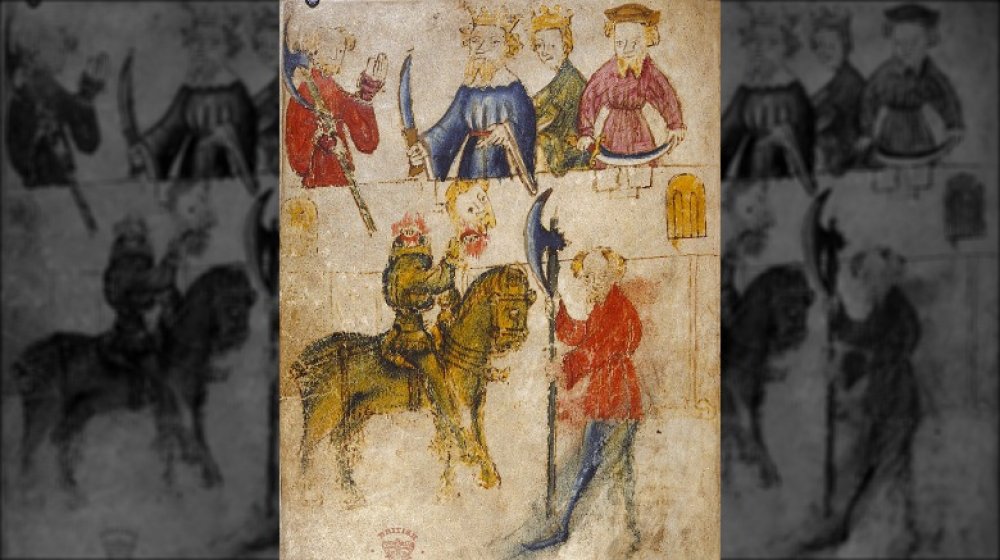

While The Pearl Poet is credited for writing the words, he wasn't the one who physically wrote the manuscript ... we don't think. According to Writers Inspire, penning the words would have been the work of a scribe, and the illustrations were done by yet another person, called a limner. The British Library describes the illustrations that accompany the text as "rudimentary" and "awkward," but you could argue that makes it even better.

How it survived... well, that goes back to the whole miracle idea. The first time it shows up in any actual records is in the early 17th century, when it was part of the library of a Yorkshireman named Henry Saville of Bank. From there, it passed into the hands of Sir Robert Cotton, who was also responsible for preserving the only surviving manuscript of another important work: Beowulf. It wasn't until the Victorian era that it was rediscovered by scholars, who finally took notice of the epic work and incredible story of one of Arthur's most devoted knights.