The Untold Truth Of The Holy Grail

Thanks to a host of movies ranging from Monty Python and the Holy Grail to Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, not to mention literature spanning from medieval epic romances to The Once and Future King to The Da Vinci Code, the Holy Grail is perhaps the best known of all the holy relics associated with the life of Jesus Christ. The search for this holy object is so ingrained in the public consciousness that the word "grail" has come to mean any object you work long and hard to obtain. Maybe a discontinued Funko Pop is your grail. Not quite a miraculous cup that might grant healing and eternal youth, but okay. We all like what we like.

But what do we really know about the Holy Grail? Does it come from the Bible, from stories of King Arthur, or what? Is it even a cup? Is it real? Where would you go to look for it? If your personal grail is having those questions answered, read on, so your personal quest may be fulfilled and you can ascend to heaven like Sir Galahad.

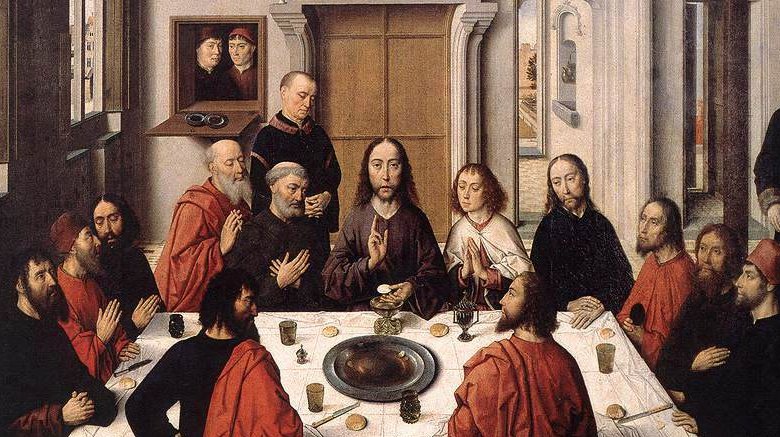

The biblical background of the Holy Grail

You probably know the basic story surrounding the Holy Grail: it was the cup used by Jesus at the Last Supper when he told his disciples to enjoy a little wine but think of it as his blood, so that's icky. According to New Advent, later, one of Jesus' followers named Joseph of Arimathea used the cup to catch Jesus' actual blood from the cross, ensuring it became a relic of unimaginable holy power. Joseph then goes to England for some reason, taking the holy cup with him, where it would become the source of much chivalric desire.

If you're only passingly familiar with the Gospels, there's a chance you might assume some or even all of that is in the Bible. In fact, the Gospels merely mention there was a cup Jesus used at the Last Supper with no special attention drawn to it, and there's certainly no mention of Joseph catching Christ's blood in it at the crucifixion. In fact, the only information we have about Joseph of Arimathea is he was a member of the Jewish high council and a devoted follower of Jesus who offered his own tomb as a burial place for Jesus after the crucifixion. Definitely no record of him hopping a plane for London. Pretty much everything we "know" about the Holy Grail first pops up in the Middle Ages.

The quest for the Holy Grail begins

The first appearance of the Grail comes in the 12th century poem Perceval, le Conte du Graal (or "Percival, the Story of the Grail") by Chrétien de Troyes. The Encyclopedia Britannica saysChretien was one of the earliest and most influential writers of Arthurian legends, and Perceval, despite being unfinished, is one of the most important. The relevant portion of the poem features our hero Percival inside the magical home of the Fisher King, where he witnesses a spectacular event: a parade of youths enter the dining hall, each carrying some miraculous item during the various courses of the meal. One boy carries a spear dripping blood, two more boys bring in candelabras, and then finally a maiden brings in a grail made of gold and studded with jewels, which illuminates the entire room. That fancy glowing cup turns out to hold a single communion wafer, which is the miraculous sustenance for the Fisher King's father, the only thing he's eaten for 12 years.

Notably, the grail in this story is called "a grail" and not "the grail," and it's definitely never called the Holy Grail or related to the Last Supper at all. And if you wonder why it was used to serve food and not drink, you're asking the right question.

What actually is a grail?

Not only is the grail of Perceval not the capital-G Grail, it's not even a cup, let alone Jesus' cup. It's a wide, shallow serving bowl, on which the readers of Chretien's poem might have expected a fish or an eel to have been served before the probably-not-as-shocking-now-as-it-would-have-been-900-years-ago twist it was a single Communion wafer. The Online Etymology Dictionary shows the origin of the word "grail" itself kind of tips us off to that fact. The English word grail comes from the Old French word graal, like we see in the title of Chretien's poem. Graal, in turn, comes from the late Latin word gradalis. This is likely a corruption of the form cratalis, which originated with the Greek word krater, and is, in fact, not a cup, but a bowl, often used for mixing wine.

So as you can see, in its earliest incarnation, "grail" doesn't even carry the connotation of cup with it. As a result, it's not so strange to understand why it would take a while for the idea of the Grail as Jesus' last cup to solidify. And bizarrely, for some authors, the Grail wasn't any kind of serving vessel at all (more on that later).

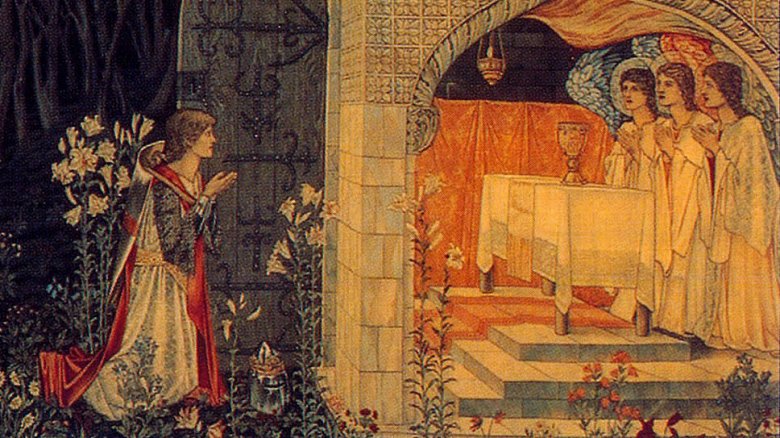

The Grail gets Holy

Where, then, does the idea of the grail as the Holy Chalice of Christ, taken to Europe by Joseph of Arimathea, come from? It didn't take long after Chretien's Perceval for the story to take shape. One of the writers who picked up the threads from Chretien's unfinished poem was Robert de Boron, who wrote a work called Joseph d'Arimathie (no extra points for guessing the translation of that title) about a decade after Perceval.

Timeless Myths says this verse romance retells the story of the last days of Jesus, adding in some additional details from popular folk belief, such as the story of Veronica, the woman who gave Jesus a cloth to wipe his face on the way to the cross, which became a famous relic known as the Veil of Veronica. This version mentions Joseph used the cup from the Last Supper to catch Christ's blood as he was moving his body into the tomb. When Jesus' body disappeared (because, well, you know what happened), Joseph was arrested under suspicion of stealing it, and he remained in prison for many years. Fortunately, Jesus appeared to him and gave him the Holy Grail, which sustained him until he was released by the emperor Vespasian. After this, Joseph and his family found a new home in the West, where he established a line of Holy Grail protectors, who eventually included Percival.

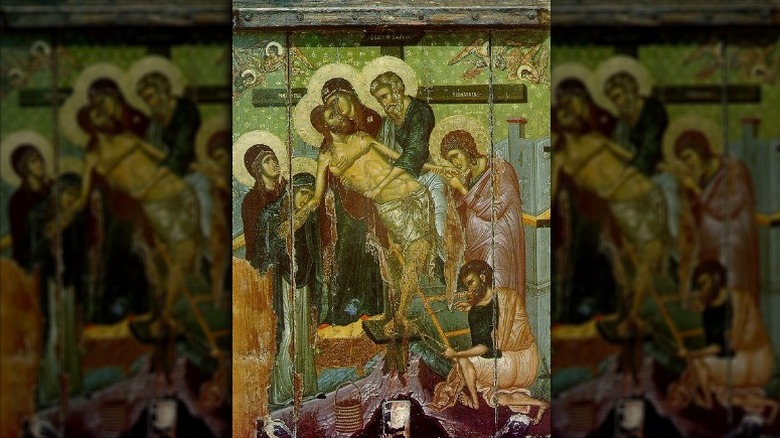

The mystery of the Fisher King, protector of the Holy Grail

Central to the Holy Grail legend is the mysterious figure of the Fisher King, a wounded monarch surrounded by a vast wasteland and the last in a long line of protectors of the Grail, descended from the family of Joseph of Arimathea. As with all things Arthurian, there are many different variations on the story of the Fisher King, but in what Mysterious Universe says is perhaps the most broadly known iteration the King is maimed when a knight named Balin stabs him in the downstairs area with the Spear of Destiny in a move that became known as the Dolorous Stroke. With the wound comes a great curse that turns the surrounding kingdom into a wasteland and leaves the king unable to do anything but fish idly in the river outside his castle. Otherwise he basically waits around for a hero who can claim the Holy Grail and heal both him and his ailing land. Percival fails in this regard because he doesn't ask the right questions about the Grail, but thankfully, later versions of the story would provide.

The enigmatic figure of the Fisher King has managed to capture the imagination of a number of creative types, inspiring works ranging from T. S. Eliot's seminal Modernist poem The Waste Land to Terry Gilliam's 1991 buddy comedy The Fisher King starring Robin Williams and Jeff Bridges to the character of Bran Stark in Game of Thrones.

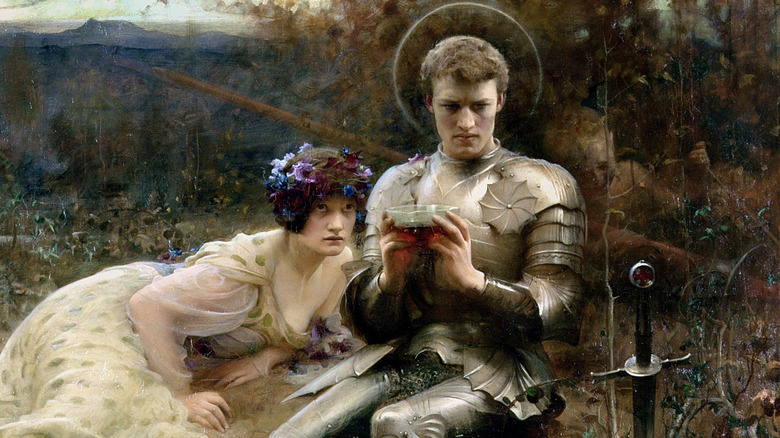

The Holy Grail Quest ends (kind of)

If you have a passing knowledge of the Knights of the Round Table and someone asked you which knight found the Holy Grail, you might guess Lancelot, the greatest of Arthur's knights. If, however, you actually paid attention in English class, you know Lancelot definitely did not win the Grail because of being the queen's sidepiece, and instead his volcel son Galahad is the one to find the Holy Grail, heal the Fisher King, restore the wasteland, and then ascend to heaven like Brian O'Conner at the end of Furious 7.

This familiar version of the story, and indeed the very character of Galahad, was added to the Arthurian mythos in a cycle of prose romances from 13th century France known variously as the Vulgate Cycle or the Lancelot-Grail, according to the aptly named Lancelot-Grail Project. The version of the story of the Holy Grail in the Vulgate Cycle borrows from both Chretien de Troyes and Robert de Boron, incorporating the Joseph of Arimathea elements (though the Grail is still described as a bowl) and downplaying the role of Percival in order to highlight the Vulgate's OC, Galahad, the chosen one who is the only one able to sit in the Siege Perilous (that is, the Danger Chair) and who makes his own adulterous dad look like a scrub. In this iteration of the story, the Holy Grail becomes a symbol of divine grace only attainable by the purest of the pure.

Did Harry Potter find the Holy Grail?

At this point, the idea of the Holy Grail as a serving vessel present at the Last Supper and used to catch the blood of Christ is pretty well entrenched in Arthurian lore, even if it's sometimes still portrayed as a dish rather than a cup. The Vulgate Cycle would be the major influence on Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, arguably the most famous version of the Arthurian cycle, itself the inspiration for T. H. White's The Once and Future King and numerous other adaptations. But one notable work of Arthuriana managed to buck the trend of interpreting the Holy Grail as Jesus' last cup and dared to ask, "What if it's a rock, actually?"

According to Jones's Celtic Encyclopedia, Wolfram von Eschenbach's 13th century poem Parzival is an epic German version of Chretien de Troyes' Perceval that manages to complete the story (Percival heals the wasteland and becomes the new Grail King) and add plenty of its own details. Namely, the Grail is in fact a stone from Lucifer's crown, which Eschenbach calls the "lapsit exillis." This is another name for the philosopher's stone, which you may remember as an alchemical object that makes you immortal and Voldemort wanted pretty bad. Eschenbach's Parzival also has the distinction of being the first work to tie the Holy Grail to the Knights Templar.

Is the Holy Grail even Christian?

Whether a serving tray holding a Holy Communion wafer, a cup that held two different versions of the blood of Christ, or a jewel from Satan's crown that can give you eternal life, at this point the Holy Grail is pretty firmly entrenched in Christian imagery and lore. Despite all that, however, there are a number of echoes in the Grail story suggesting maybe the tale of this miraculous vessel pulled a not insignificant amount of influence from pre-Christian Celtic myth.

Notably, the Fisher King bears more than a passing resemblance to the legendary Celtic god-king Bran the Blessed, who features heavily in the cycle of medieval Welsh legends known as the Mabinogion. Bran has a miraculous cauldron he can use to restore the dead to life and grant wisdom, as well as having a spear wound on his leg. Legend of King Arthur records Bran himself (or rather his magical severed head) become a part of Arthur's story as well, and some argue Robert de Boron's Grail King (Bron) is taken from Bran. Despite these similarities and the prevalence of cauldrons in Celtic myth, however, not all scholars are convinced the Holy Grail has Celtic origins, arguing that the imagery surrounding the Grail is purely Christian in nature. The similarities between Bran and Bron are pretty hard to overlook, though.

The Da Vinci Holy Grail Hoax

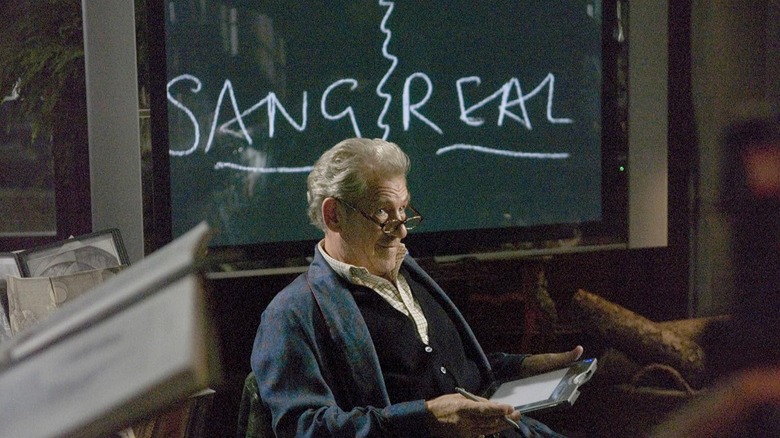

Up until this point, we've looked at how maybe the Holy Grail is a cup or a bowl or maybe it's a magic rock that grants immortality, but the question some punk rock intellectual rebels have dared to ask is, "What if the Grail isn't an object at all? What if it's a person? What if it's a lot of people? [cool sunglasses emoji implied in the inflection of their voice]" This idea stretches back as far as the 15th century, when English writer John Hardyng presumably got really stoned and then asked, "Whoa, man, what if sangreal [Old French for Holy Grail] wasn't san-greal, but sang-real [that is, "royal blood"]?"

From this completely fake etymology (remember it was just a grail before it got holy), a whole cottage industry has sprung up around the idea that rather than a blessed relic from the Last Supper, the Sangreal is in fact the secret bloodline of Jesus with his secret wife, Mary Magdalene. Salon reports this was the premise behind the "non"-fiction early '80s best-seller Holy Blood, Holy Grail and perhaps more famously of the early 2000s cultural phenomenon that ripped it off, Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code. If it weren't enough this theory is already founded on completely shaky ground that ignores the literary origin of the Grail, Holy Blood and Brown pile layer after layer of made up history on their theory.

The Holy Grail conspiracy

Setting aside the fact that the very idea of the Holy Grail actually being a descendant of Jesus is roughly the same as someone a few hundred years from now saying, "Yes, lightsabers were real and also Abraham Lincoln was killed by one, but actually the lightsaber was a person–John Wilkes Booth–who was a secret descendant of Socrates whose family was protected by SEAL Team 6," some of the conspiracy theories behind the Holy Grail require some real misinterpretation of history. Following the mention of a military order called the Templeise that help protect the Holy Grail in Eschenbach's Parzival, History says various writers have embroiled the Knights Templar in conspiracy theories surrounding the Grail. The Templars–around whom there is admittedly some mystery regarding their secret initiation ceremony–have been said to be the protectors of the Holy Grail, be it cup, bloodline, or just secret knowledge, but there is no historical evidence linking them to any non-fictional Grail quest.

Further complications involving Gnostic Christian movements like the Cathars are reliant upon the existence of the hoax secret society the Priory of Sion result in the kind of theories that make Salon call Holy Blood, Holy Grail a masterpiece "as enormous crocks of nonsense go." Then on top of that saying Da Vinci hid clues in his art about it is like saying Shepard Fairey's portrait of Obama includes secret hints to the existence of lightsabers.

So many Holy Grails to see

If you ignore the idea of the Holy Grail as the Arthurian artifact protected by the family line of Joseph of Arimathea or the Knights Templar or whatever, the idea of a cup that Jesus used one time is much easier to accept. Consequently, a number of locations claim to have in their possession the Holy Chalice (as distinct from the somewhat more loaded term, Grail) that you can go visit if you are so inclined.

In 2018, a pair of historians claimed to have found the authentic Grail in the Basilica of San Isidoro in Leon, Spain, where the much bedazzled cup has long been known as the chalice of the Infanta Doña Urraca for centuries. They back their claim up by using manuscripts they found describing the cup as one brought to Spain from the Holy Land via Egypt, but their claim would likely be refuted by the Cathedral of San Lorenzo in Genoa, Italy, whose Sacro Catino they assert to have been Jesus's own from the Last Supper, "rescued" during the Crusades. Meanwhile, Atlas Obscura says the Chapel of the Holy Grail in Valencia, Spain, claims that their cup was brought to them via Rome by St. Peter himself, and the so-called Nanteos Cup in the National Library of Wales has a long reputation of being the Holy Grail due to alleged healing powers. There is, of course, no shortage of other contenders.

Where to start your quest for the Holy Grail

If, however, you believe that the Holy Grail is real but that none of those contenders resemble the simple "cup of a carpenter" that Indiana Jones was looking for, there are some potential locations associated with the Grail where you could start your own search. According to Robert de Boron, Joseph of Arimathea delivered the Grail to the valleys of Avalon, a location which since the 12th century has been associated with Glastonbury in Somerset, England. Legend even states that the first of the famous Glastonbury Thorn trees sprung up from a spot where Joseph thrust his staff into the ground. Allegedly Joseph's grave can be found in Glastonbury as well, so it seems like a logical spot to begin your personal quest.

The association of the Cathars with Grail conspiracy theories has led people since the early 20th century to believe that the Grail could be found at the Cathar castle known as the Chateau de Montsegur, which is believed to be the Grail Castle from Eschenbach's Parzival. Notable people convinced of this include Richard Wagner, who went there to research the Grail for his opera Parzifal, and Heinrich Himmler, who sent some spooky Nazi boys hoping they could win the war with Jesus' magic cup. If you'd rather go to Scotland, however, trek out to Rosslyn Chapel, whose walls are alleged to contain the secret treasures of the Templars, including one mostly fictional cup.