Things About These Presidents That Don't Make Sense

Democrats think Republican presidents don't make sense. Republicans think Democratic presidents don't make sense. And if the Federalists and Whigs were still around, they'd probably be shaking their powdered wigs at everybody. But regardless of politics, we can all agree — some things about U.S. presidents are just plain baffling, no matter which way you look at them. In fact, some are downright bizarre, like Abraham Lincoln's haunting premonitions and Jimmy Carter's brush with a UFO.

There have also been some equally questionable decisions, including William Henry Harrison's choice to deliver a marathon inaugural speech in the freezing rain and Teddy Roosevelt's impromptu deep dive into the Amazon jungle. And then there are those mysteries still hanging around, from George Washington's missing Capitol cornerstone to the murky circumstances of Warren Harding's demise. These senseless stories reveal the all-too-human side of our commanders-in-chief — and in some cases, their surprisingly superhuman side, too.

George Washington's missing Capitol cornerstone

In 1793, George Washington traveled from the construction site of the White House to the not-yet-existent U.S. Capitol. Once there, he climbed down into a foundation trench, placed an engraved silver plate, and the very first cornerstone of the Capitol building was laid upon it, in the southeast corner. Then came the party — music, fanfare, and a 500-pound barbecued ox.

But all that revelry has transformed into one of the longest-running unsolved mysteries in American architecture, as nobody seems to know where that cornerstone is anymore. But how does a large chunk of rock, which may weigh several tons, get lost? It turns out that "southeast corner" isn't exactly GPS-specific. Is it the southeast corner of the first completed section, on the Senate side? Or the one that would eventually be the full building's southeast corner, on the House side?

There have been numerous efforts to crack the case. In 1893, the Architect of the Capitol hoped to mark the Capitol's 100th birthday with a nice "look what we found!" moment, but with no luck. The 1950s added metal detectors to the search, which was again unsuccessful. Even the U.S. Geological Survey got involved — and came up empty. In 1991, hopes were briefly raised when a suspiciously cornerstone-ish 5-foot slab turned up beneath the House of Representatives' basement coffee shop. But after more digging, the engraved silver plate was nowhere to be found. The original Capitol cornerstone — handled by Washington himself in the city that bears his name — remains MIA.

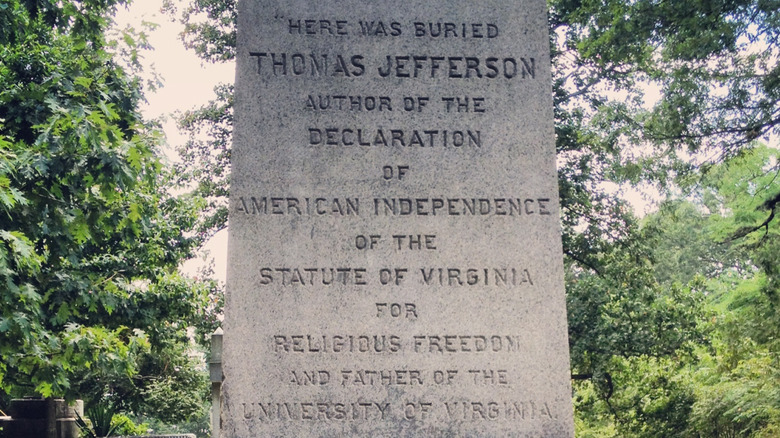

Thomas Jefferson left 'President' off his tombstone

Thomas Jefferson wasn't just a Founding Father, he was also something of a micromanager, at least when it came to his own legacy. Jefferson wrote out explicit instructions for his gravestone, with a sketch of the monument and the specific inscription he wanted (via Monticello): "Here was buried — Thomas Jefferson — Author of the Declaration of American Independence — of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom — & Father of the University of Virginia." And that was it, as he instructed: "not a word more."

But with that inscription, there's a major detail left off of Jefferson's gravestone. His instructions failed to mention his service as the third president of the United States. Of course, he couldn't list everything — it's a gravestone, not a resume. He also left off governor, secretary of state, vice president, architect, lawyer, philosopher, and so many more. But why snub the presidency? Much of the country loved him in the role: he won re-election in a 162-to-14 electoral landslide, doubled the nation with the Louisiana Purchase, and served an influential role on the world stage.

While Jefferson's humility or disdain for centralized power might explain the omission, his service as president was central to both his life and the country's trajectory, and so it would seem worthy of a line on his tombstone. But the former president didn't think so. And, even in death, Jefferson made sure he got the last (but not too many) words.

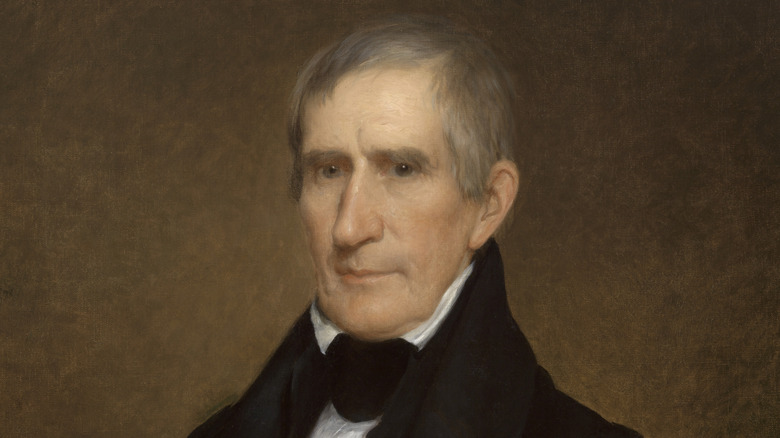

William Henry Harrison's long, cold, and probably deadly inaugural address

Did William Henry Harrison talk himself out of a job? He gave the longest inaugural address in U.S. history, which in a bizarre twist may have led to him serving the shortest presidential term. The speech took place on March 4, 1841, a cold, wet, miserable day in Washington, D.C, when most people would bundle up in every layer they owned. Not Harrison: The 68-year-old president-elect decided this was the perfect moment to forgo a coat, hat, or gloves. His speech — over 8,400 words long — rambled on for nearly two hours, in the cold and rain. Nearly two centuries later, it's still one of the most awkward inauguration day moments in history.

This was before TikTok, Netflix, or even radio, and so long speeches were themselves a form of entertainment. But even by 19th-century standards, Harrison was excessive. The eight presidents before him averaged around 2,000 words for each of their inaugural addresses. Harrison quadrupled that, seemingly undeterred by the bone-chilling drizzle.

A month later, he was dead, and for decades, the blame fell on that speech. The tale went that he caught a cold that day, which progressed into fatal pneumonia. Experts now think it was enteric fever, likely from contaminated water. But even if it wasn't the rain-soaked speech that did him in, it's hard not to wonder — why did a 68-year-old man think it was a good idea to stand coatless in freezing rain and deliver the audiobook version of an inauguration speech? If nothing else, it's one of history's more baffling mic drops.

Abraham Lincoln's eerie dreams

Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, is one of the giants — figuratively and literally — of U.S. history. He was also a guy with a knack for unsettling dreams and the unfortunate habit of remembering them. As an eerie example, Lincoln once telegraphed his wife about "an ugly dream" he'd had involving their son, Tad, and that she should keep Tad's pistol out of easy reach.

An even creepier dream came a few nights before Lincoln's assassination. According to "Recollections of Abraham Lincoln," written by Ward Hill Lamon, a close friend, former law partner, and sometimes bodyguard (Lamon wasn't around the night Lincoln was killed), the president shared the dream with just a few trusted people. In the dream, Lincoln woke up to the sound of crying. He wandered through the White House, searching for the source of the sobbing, and upon entering the East Room, he saw a covered corpse, where soldiers stood guard and mourners wept. When Lincoln asked who had died, a soldier replied, "The President. He was killed by an assassin!"

And that's when he woke up, unable to sleep again that night and thoroughly rattled. Did Lincoln predict his own death? Lincoln tried to brush it off, telling Lamon that it wasn't him in the dream, just some "other fellow." Still, Lamon remembered how disturbed the president had seemed, and that the dream wouldn't leave him alone.

Ulysses S. Grant's financial downfall

You'd think the man who led the Union to victory in the Civil War would be good at spotting a bad guy. But when it came to money, former President Ulysses Grant may have laid down his defenses a little too easily. A fraudster named Ferdinand Ward ran what we now call a Ponzi scheme, but he dressed it up with some name recognition: "Grant and Ward," but not of President Grant, but rather his son, "Buck" Grant.

When the retired president learned that "Grant and Ward" was financially unstable, he turned to the railroad titan William Vanderbilt for help. Vanderbilt warned Grant that the firm smelled fishy and said he wouldn't even lend it a dime. But as a personal favor to Grant, Vanderbilt handed over $150,000, which went to "Grant and Ward." The next day, Ward and all the money disappeared, leaving President Grant and his wife with only $210 between them.

To make matters worse, Grant was diagnosed with terminal throat cancer and was terrified about leaving his wife with nothing. He rushed to finish his memoirs, which did earn financial security for his family, but Grant almost left his wife as a broke widow. How Grant lost all his money really doesn't make much sense. Was it a desperate attempt to help his son's so-called company? Was he simply duped by a charming fraudster? Whatever the explanation, thankfully, Grant was able to replace poor financial literacy with literary success.

Benjamin Harrison's fear of light switches

Electric lighting was an exciting and rapidly developing technology in the late 1800s, when President Benjamin Harrison decided the White House needed to join in. The man tasked with flipping the switch from gas to electricity was Irwin "Ike" Hoover, an employee of the Edison Company. Ike wired and installed electric lighting, transforming elegant gas chandeliers into modern electric fixtures. But there was just one problem: the Harrisons were afraid to touch the light switches.

While the president wanted the new lighting to signal America's embrace of technological innovation, neither he nor his family wanted anything to do with turning the power on or off. If no one was around to operate the switches, the Harrisons just sat in the dark. In the evenings, Ike would roam the White House turning on the lights in the halls and parlors, and those lights usually stayed on all night. No one in the Harrison family wanted to risk a shock at bedtime.

When electric bells were installed to summon staff, they were met with the same suspicion. According to Ike, ringing the bell often required an emergency family meeting, presumably with hushed debate and crossed fingers before anyone dared to poke the button.

Teddy Roosevelt's reckless Amazon expedition

When a museum in Buenos Aires invited Teddy Roosevelt to give a series of lectures, the former president thought he might add a little scientific adventure to the trip. He reached out to his longtime pal Henry Fairfield Osborn, president of the American Museum of Natural History, who enthusiastically offered his support. At this point, the plan was fairly tame: a specimen-collecting cruise along established, relatively safe waterways.

Then, as Roosevelt put it in his book "Through the Brazilian Wilderness," "... the expedition was enlarged." He decided to chart an unexplored river with the ominous name of the River of Doubt, but there was no doubt about the dangers that'd be waiting in the jungle, such as white-water rapids, malaria, starvation, storms, and venomous creatures. Upon learning of the change of plans, the American Museum of Natural History was not thrilled. One naturalist flat-out said that this new journey wasn't just risky; it was the most dangerous route in South America. Osborn implored Roosevelt to stick to the original plan, believing the new plan was a borderline death wish..

Months of careful planning for the original trip were rendered useless. They had the wrong boats, too much luggage, and none of the gear they actually needed. Three men didn't make it out alive, and Roosevelt, still recovering from an assassination attempt and with basically zero jungle experience, came terrifyingly close to dying himself.

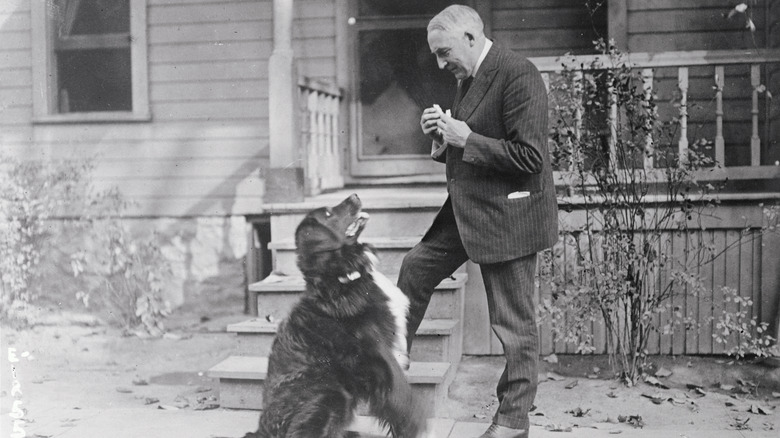

Warren Harding's mysterious death

Over a century later, we still don't know for sure how President Warren Harding died. Harding's final moments were spent at San Francisco's Palace Hotel, while his wife, Florence, read him the "Saturday Evening Post." Somewhere between the pages, Harding slumped over and died.

The official announcement called it a stroke. But Florence refused an autopsy and ordered an express embalming. This fast-tracked rumors of foul play, which in turn led to accusations of murder, concerns about death by suicide, and conspiracy theories about Harding's death.

Modern medical minds now believe Harding most likely suffered a heart attack. He'd shown signs of congestive heart disease for years, but those indicators weren't recognized in the early 1920s. And on the theme of outdated medical practices, Harding's preferred doctor — who, awkwardly, wasn't actually a trained doctor — may have unintentionally killed the president with strong purgatives meant to cleanse the system. Instead, they would have aggravated Harding's heart condition, hastening his death.

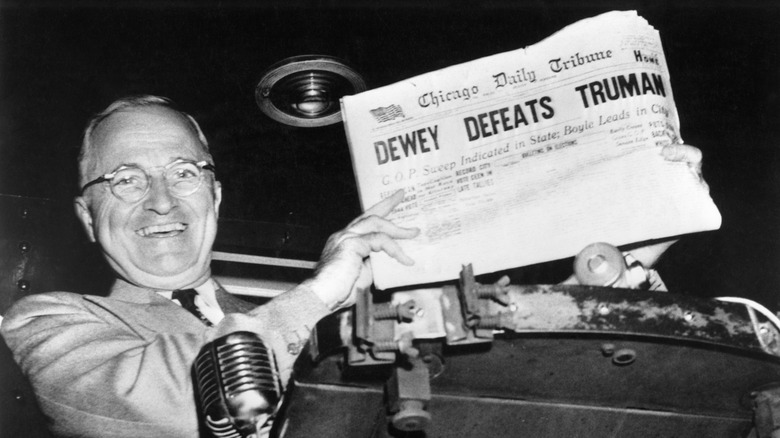

Harry Truman's unexpected political upset

When Harry S. Truman became president in 1945, it was under grim circumstances. Franklin D. Roosevelt had died in office while World War II still raged, and Truman suddenly found himself leading a nation at war. Despite winning said war, the rocky start only got worse, and by the 1948 election year, Truman's approval ratings had dipped into the 30s. Nearly everyone — pollsters, pundits, his own party, and reportedly even his wife — figured he'd be packing by January the following year.

Five weeks before Election Day, The New York Times described how analysts thought Truman's defeat to his opponent in the 1948 presidential election, Thomas Dewey, was "practically certain," and editorials popped up suggesting that Truman should quit the race. Just days before the election, Life magazine ran a large picture of Dewey with a caption calling him "The next president." And then, in one of the most infamous face-palms in media history, the Chicago Daily Tribune ran the front-page headline: "Dewey Defeats Truman."

If you're scratching your head because you can't remember a thing about President Dewey, that's because he never won. Despite the big, bold letters on the front page of a well-known newspaper, Dewey didn't really defeat Truman in the 1948 election. Truman pulled off a win so shocking that historians still call it one of the greatest election upsets in U.S. history. It's hard to say what's more baffling — a supposedly unpopular incumbent pulling off a miracle win, or every major pollster in the country missing it by a mile.

John F. Kennedy's mood depended on his scales

When John F. Kennedy lived at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, he had access to the White House's indoor swimming pool. He used it frequently, likely enjoying the exercise and some relief for his ailing back. And after every swim, Kennedy would hop on a scale and weigh himself.

Dave Powers, JFK's close friend and assistant, commented on how the president's mood could shift depending on what the scale told him, and JFK expressed his body image issues with another friend, Paul Fay, including that he thought his face was starting to show his age. JFK was so focused on his physical image that he even traveled with a bathroom scale. Among all the things loaded onto Air Force One, there'd be a presidential scale somewhere in the luggage.

However, at 6 feet and 1 inch tall and about 175 pounds, JFK was not considered overweight. On the other hand, he had very publicly promoted physical fitness on the national level, both before and during his presidency, which likely contributed to his image fixation.

Jimmy Carter's UFO sighting

Jimmy Carter couldn't make sense of what he saw one night in 1969, years before he became the 39th president of the United States. It was shortly after dark and the stars were out in tiny Leary, Georgia, when Carter was standing outside a Lions Club meeting with about a dozen others. Suddenly, a luminous light — as bright and almost as big as the moon — glided in from the horizon. Carter said it paused, drifted away, zipped back, and then took off like it remembered it left the iron on. At one point, the thing even cycled through a patriotic light show of blue, red, and white.

Carter was so struck by the sighting that he filed an official UFO report in 1973 with the National Investigations Committee on Aerial Phenomena. Ever the gentleman, he later told reporters he'd never mock anyone who claimed to see a UFO, since he'd seen one, too. During his 1976 campaign, he even promised to release any government information about UFOs to the public. But when he took office, Carter walked that pledge back, citing national security, and even in his later years, we came no closer to understanding the truth about Carter's UFO sighting; in 2005, he simply stated the obvious to GQ: "It was a flying object that was unidentified."

George H.W. Bush somehow survived a WWII plane crash

It's hard to picture George H.W. Bush, the buttoned-up statesman who loved a good martini, as a young pilot dodging death in the Pacific Theatre of World War II. But at just 20 years old, Bush was doing exactly that, and he barely made it to his 21st birthday. He flew an Avenger, a torpedo bomber, one of which he managed to crash land in a practice run — and that was before anyone started shooting at him.

On one mission, Bush and two crewmates were flying when enemy antiaircraft fire hit their plane. The wings caught fire, smoke choked the cockpit, and flames raced towards the fuel tanks. At about 1,500 feet, Bush jumped out. He hit his head on the way down and ripped his parachute, but by some miracle, he splashed down alive. Sadly, his gunner's chute never opened, and the radioman went down with the plane.

In the ocean, Bush became nauseous, likely a combination of his head injury, jellyfish stings, and swallowing too much salt water. But he managed to cling to a life raft as an enemy boat pursued him. An overhead plane held the enemy off, buying Bush a few anxious hours until a submarine surfaced and pulled him aboard (pictured above). He spent the next 30 days underwater, feeling helpless when depth charges attacked the sub, an experience he considered to be worse than flying through antiaircraft fire.