Bizarre Artifacts Found From The Revolutionary War Era

Human beings have always been a little strange, and that was no different during the Revolutionary War period. So when archaeologists find artifacts from that era, every now and then, they are a bit, well, weird. The kind of things that make you wonder about just what the person who left it there was thinking.

Other times, it is not the item itself that is bizarre, but rather how it ended up where it did, how it managed to last so long, or the extraordinary circumstances under which it was discovered. In a couple of cases, it wasn't even an expert who found the strange artifact in question, adding another layer of the unexpected.

New discoveries are being made all the time, even 250 years after the colonies broke away from the British. There is no doubt that right now, buried in the earth or stuck in a dusty box, are more strange items from the period just waiting for a curious person to stumble across them. Here are some of the bizarre artifacts archaeologists have found from the Revolutionary War era.

Musket balls with teeth marks

Colonial Williamsburg continues to reveal secrets of early America after all these years. In 2024, archaeologists uncovered evidence of a Revolutionary War barracks that a British general tried to destroy. The team found several interesting artifacts from the time period, including musket balls that had been chewed on. It's pretty uncommon to find ammunition that soldiers noshed on a couple hundred years ago, but it does happen occasionally; several examples were also found at Fort Ticonderoga. What historians can't agree on is why anyone did it in the first place.

One theory is that a rough musket ball would cause rougher wounds, therefore making it harder for them to heal and more likely to result in the death of an enemy soldier. Or the teeth marks could be filled with some kind of poison to make them deadlier. Soldiers at the time seemed to believe this was the case. After the Battle of Bunker Hill, British Lieutenant John Waller wrote to an unknown recipient, "The army is in great spirits, and full of rage and ferocity at the rebellious rascals, who both poisoned and chewed the musket balls, in order to make them the more fatal" (via Teaching American History).

One disputed theory is that soldiers chewed the musket balls during surgery to try to block out the pain. Other writings indicate they relieved thirst. And still other historians believe bored soldiers liked biting them because the ammo tasted sweet, and chewing gum wasn't an option yet.

A tragic letter from a Black soldier

In 2020, while sifting through 20th-century documents in a moldy cardboard box, Patrick Donovan, curator at the Varnum Memorial Armory Museum, discovered an astonishing letter. Written in 1781, it was a letter from a Black Revolutionary War soldier, one of only two such letters known to exist.

A small number of Black soldiers fought in that conflict as members of the First Rhode Island Regiment. To bolster their decimated ranks, the Army decided to offer freedom to enslaved Black men who would enlist for the duration of the war, and whose enslavers agreed to the plan (enslavers were also compensated by the state for their loss). The idea was not popular, with only 90 enslaved men taking up the offer, and fewer than 200 men of color total making up the ranks.

Despite their small number, the men of the regiment served bravely and saw serious combat. But war is hell, and not everyone is cut out to be a soldier. The letter Donovan discovered was a pleading note from Thomas Nichols, a former enslaved man, to his former enslavers, Benjamin and Phoebe Nichols. He wanted to leave the military and return to them. He wrote, [sic] "...I have a desire that Master or Mistress would ... see if you cant git me Discharged from ye War, it being very Disagreabell to my mind as well as Destructive to my helth..." (via EG News). While he was listed as an invalid and given less stressful duties, Nichols was not allowed to leave the Army.

Magic wand or cheese grater?

In 2021, a dendrochronologist (a scientist whose expertise is tree rings) was working at the Schuyler House, a Revolutionary-era home in Saratoga National Historical Park. Owned by General Philip Schuyler, a member of the Continental Congress and later a U.S. senator, the present house was built in 1777 after the British burned it during a retreat from battle. (It was actually his country home; the well-to-do general's city home, the Schuyler Mansion in Albany, New York, is a state historic site.) Because he needed to build a home on the site quickly after the previous one was destroyed, Schuyler went with something much less grand. He did not even add a proper kitchen until 1780.

It was in this kitchen that the dendrochronologist was working when they found a weird-looking artifact in a crawl space. Described by the Centre Daily Times as looking like "a kind of rustic magic wand," it wasn't immediately clear what strange treasure had been discovered. Would this become another unsolved mystery of Colonial America?

In the end, no. The Saratoga National Historical Park's Facebook account revealed that experts had determined the item was a cheese grater, made from wood that probably came from an old bucket. While there is some evidence that it may date from a slightly later period, between 1785 and 1820, the kitchen implement is still associated with this important Revolutionary War location.

Perfectly preserved fruit

George Washington's Mount Vernon is a monument to the first president that is visited by thousands of people a year, but it is also an active archeological site. In 2024, during a $40 million revitalization project, archaeologists were digging in five storage pits underneath the mansion's kitchen and discovered 35 18th-century glass bottles. An astonishing 29 of them were intact, most of which contained perfectly preserved cherries, gooseberries, and currents. (One species not included in the amazing find was George Washington's favorite fruit, the pawpaw. Perhaps this quickly-spoiling fruit did not make good preserves. Or maybe there were none left because he ate his favorite kind first!)

This was an almost unprecedented find. Mount Vernon Principal Archaeologist Jason Boroughs said, "These perfectly preserved fruits picked and prepared more than 250 years ago provide an incredibly rare opportunity to contribute to our knowledge of the 18th-century environment, plantation foodways, and the origins of American cuisine." However, the information gleaned from the discovery will also help reveal a different story. Boroughs explained, "The bottles and contents are a testament to the knowledge and skill of the enslaved people who managed the food preparations from tree to table, including Doll, the cook brought to Mount Vernon by Martha Washington in 1759 and charged with oversight of the estate's kitchen."

Most remarkably, there is hope that some of the 54 cherry pits extracted from the bottles could be planted to grow an 18th-century tree of George Washington's in the 21st century.

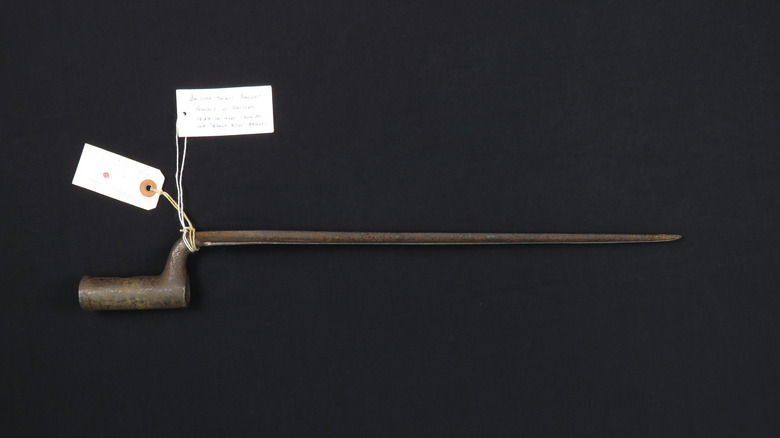

A cache of 30 bayonets

Bayonets were used regularly by soldiers on both sides of the Revolutionary War, often proving more useful at defeating the enemy than the muskets they were attached to. Since they were so ubiquitous, it might not seem like they would be a rare discovery on archeological digs at sites from the period. In actuality, finding even a single Revolutionary War bayonet is a big deal, so archeologists at Valley Forge National Park got a big shock on the last day of a years-long dig in 2017.

The group wasn't expecting to find anything, assuming they had already thoroughly excavated the site. So when a metal detector pinged on a single bayonet, it was a shock — then they discovered 29 more. "I haven't seen anything else like it in a single excavation. It looked like someone had dug a hole in the ground and threw them in there," Jesse West-Rosenthal, a Temple University Ph.D. candidate in archaeology, told Atlas Obscura.

For a brand-new army that was really just making it up as it went along, leaving behind so many valuable weapons in the middle of the war seems crazy. However, the encampment at Valley Forge coincided with the period when France entered the war on the side of the colonies, pretty much saving their butts. "It's very possible that this was a discarded collection of materials that may have been replaced by new, more formalized weaponry coming, especially as France starts to supply the army," says West-Rosenthal.

Dice made from musket shot

There is a famous saying in the military: "War is months of boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror." No one knows who first said it, but the earliest use of a similar quote dates back to the First World War, according to The National WWI Museum and Memorial. While no one who participated in previous wars appears to have written that sentiment down, it is almost certain that soldiers felt the same way in all wars throughout time.

Boredom means finding any way you can to pass the time, even with limited resources. During the Revolutionary War, soldiers often entertained themselves by gambling and created makeshift dice out of whatever materials they had handy. This included bones and musket shot, and the ammunition was especially good since the soft lead was easier to mold into shape. Several examples have been discovered, some by amateur archaeologists and metal detectorists, including at places like Valley Forge.

These discoveries also demonstrate how quickly those in charge of the colonies abandoned their early efforts to control vice among the population. After being founded by very straight-laced religious groups, places like Jamestown tried to ban gambling. While gambling is mentioned in the Bible, usually in a negative manner, the holy book doesn't actually say, "Thou shalt not gamble," so soldiers and citizens alike partook in games of chance during their downtime.

A log cabin inside another building

In 2020, residents in Washingtonville, Pennsylvania, were probably thrilled that a town eyesore, an old, condemned bar, was finally being torn down. Frank Dombroski, borough council president, told Newsweek, "The building was just your local small town bar when it was in operation. It had closed probably about 12 years ago and had been condemned about 3.5 years ago. The building was in bad shape for a long time."

The contractors doing the teardown knew not to trash everything, though. "We knew going through the building there were some beams in the back of the old bar room that we wanted to salvage because they were so beautiful," Mayor Tyler Dombroski (son of Frank) told The Daily Item. The town was about to get so much more from the old bar than it expected: inside its walls was a two-story, Revolutionary War-era house. Tyler explained, "As the contractor started to peel off the additions to the building from over the years, we started to see exposed beams, and then the entire log cabin. Everybody's jaws dropped because it's a very old structure — probably 200 years old."

The town came together to save as much of the historic find as possible. The Montour Delong Fair Association purchased the building for a dollar and rebuilt it at the fairgrounds, although there was only enough salvageable material for a one-story version of the original structure. It is now used as a small museum and event space with period-appropriate reenactments.

Gunboat found at Ground Zero

In 2010, while preparing the land at Ground Zero for the construction of One World Trade Center, archaeologists discovered a gunboat that would have patrolled the Hudson River in the 1770s. This was an incredible find, but it became a race against time to remove the wood and get it to a suitable environment. After so long buried in the earth, just exposure to air could quickly destroy the 250-year-old lumber.

Getting it out safely was going to be so difficult that some were against even attempting it. "The original plan of the Port Authority was to record it solely with photos. It was the [Lower Manhattan Development Corporation] and its staff and board that insisted on this level of preservation as an artifact," the president of that organization, David Emil, told The New York Times. The majority of the boat was able to be retrieved, and the World Trade Center Ship was unofficially named the S.S. Adrian in honor of Joaquim "Adrian" Medeiros, who supervised the construction crew that carefully removed the fragile timbers.

From New York, the boat pieces were sent to the Archaeological Watercraft and Aircraft Conservation at Texas A&M University, where experts spent the next 15 years working to preserve them. It was only in 2025 that the boat was in good enough shape to go to its permanent home at The New York State Museum. There, preservation work continued, now in full view of the public.

A scrap of George Washington's mess tent

When someone donates something that might have real value to Goodwill, the charity puts it in online auctions. Richard "Dana" Moore was browsing one of these sales, looking for something cool, when he came across a small piece of fabric. What made it interesting was an old note attached to it, claiming it came from one of George Washington's military tents. Although there was no evidence to support the claim, Moore took a chance and won the lot with a $1,300 bid.

Spending that chunk of change on a gut feeling was risky, so much so that Moore didn't even tell his wife for a little bit. But it paid off. After experts were contacted, the piece of fabric was authenticated as part of the marquee dining tent Washington used on campaigns during the Revolutionary War. The piece had been pilfered in 1907 from the Jamestown 300th anniversary exposition in Norfolk, Virginia, by a mysterious man named John Burns, who was just a random attendee of the event.

Matthew Skic, curator of the exhibition "Witness to Revolution: The Unlikely Travels of Washington's Tent" (seen above, which included Moore's find as one of its displays) at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia, told WHYY, "We're trying to figure out more about this person, John Burns, and his relationship to the exhibition. We're still actively trying to figure out more of the context surrounding this 'borrowing' of a fragment of George Washington's dining marquee."

Paul Revere's outhouse, maybe

Paul Revere founded America's first spy ring, went on a midnight ride to warn the colonists that the British were coming, and all while having a pretty cool job as a silversmith. Paul Revere's home still exists in Boston, where the Revolutionary lived next to his cousin, Nathaniel Hichborn. The unexpected 2017 discovery of a privy in the backyard of Hichborn's home resulted in several amazing findings, even if it can't be proved any of the poop was the product of his more famous relative.

Yes, sometimes archeologists go through cesspits looking for human poop. As archaeologist Joe Bagley, who was working on the Hichborn dig, told WBZ NewsRadio 1030 (via CBS News), "We're hoping to find the individuals' waste themselves ... we can get seeds from what they were eating, we can find parasites, find out what their health was ..."

The fact that these early toilets doubled as garbage dumps makes them even more valuable from a historical perspective. As Bagley explained to Boston Magazine, "Back in the days before trash pick up started at the end of the 1800s, your choices for what to do with all your garbage were to bury it somewhere in your yard, throw it in the ocean, or just throw it across the yard itself. ... There tend to be secrets in them." Strange rubbish in the Hichborn privy included a huge piece of Caribbean coral and part of an Italian porcelain plate from the 1630s — making it almost the oldest pottery ever found in Boston.

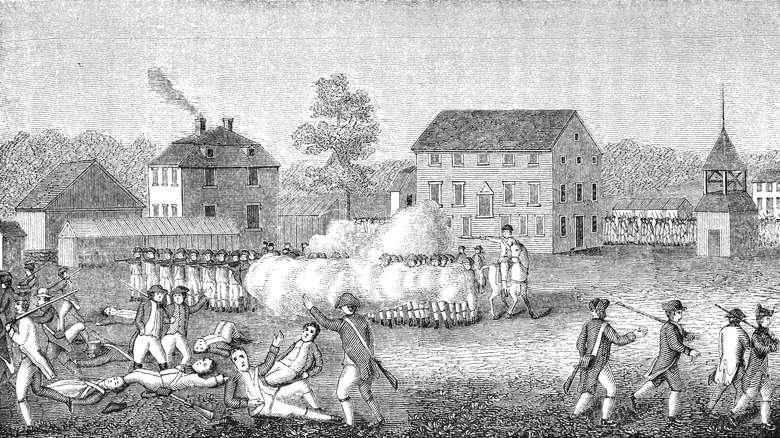

The first map of the war's first battle

As famous as the Battles of Lexington and Concord are for their dramatic effect on world history, how exactly they played out is a bit more vague than you might expect. This was not a planned skirmish, after all, with battlefield plans and organized regiments on both sides. It was very fortunate for future historians that just hours after the two sides exchanged fire at Lexington on April 19, 1775, the British commander, Lieutenant General Hugh Percy, sketched a map of the battle.

Then, virtually no one else saw it for centuries. Lord Percy returned to his home country early in the war. For almost 250 years, this map was stored among other papers in a box owned by the Dukes of Northumberland on their estate in northern England, without anyone realizing its significance. A team from American Heritage cataloged the map among others in the 1960s, but it was only in 2024 that another group from the publication analyzed it.

The map is not just useful for its military significance, but also for the details Percy included that show the lay of the land in the area. "He's sketching the line of march," local historian Michael Ruderman said upon seeing the map (via American Heritage). "It's the theatre of battle, the hostile territory he had to travel during the afternoon. And he's sketching the landmarks that were significant to him, like the Old Powder House tower that he passed on his left."