TV Shows Historians Absolutely Hate

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Television has often looked to the past for inspiration, and some of TV's most popular shows delve into the mists of history. These shows have really run the gamut, ranging from a cartoon sitcom about a stone-age family ("The Flintstones") to a long-running drama set in the Old West ("Gunsmoke") to an award-winning series focused on Britain's royal family during the reign of Queen Elizabeth II ("The Crown"). Even futuristic sci-fi series such as "Star Trek" regularly travel back in time to bygone eras. But while historical series may be embraced by viewers, that hasn't always been the case with actual historians.

The folks who produce TV series realize they're not creating documentaries, and tend to take plenty of creative license when it comes to historical facts. The rule of thumb is generally that historical accuracy should never stand in the way of a juicy storyline. For those who have devoted their lives to the study and preservation of history, however, that disdain for facts can prove irksome. That is especially the case when viewers take what they're watching as gospel, not realizing that a historical drama is likely to contain more drama than actual history. Consequently, there are some TV shows that historians absolutely hate.

The Tudors

The messed-up truth of Henry VIII was at the core of "The Tudors," focusing on the turbulent, wife-murdering reign of the Tudor monarch (played by Jonathan Rhys Meyers).

Right off the bat, the show was hit with backlash over its myriad historical flubs, beginning with Henry's permanently ultra-fit, gym-built physique. While Henry was very athletic as a young man, the Tudor monarch was considerably heavier in his later years, reportedly so much so that he had difficulty walking. Another of the show's various historical goofs was one pretty major one: according to "The Tudors," Henry faced off with Pope Paul III (played by Peter O'Toole) in his quest to have his marriage annulled, while in actuality he tussled with a whole other pontiff, Clement VII.

Those flubs, however, were just two of many that infuriated historian David Starkey. "'The Tudors' is terrible history with no point," Starkey said, as reported by The Guardian. While Starkey acknowledged the necessity to take some license when dramatizing history, he slammed the series' writers for ignoring historical fact just because they could. "It's wrong for no purpose," he complained. "But it's the randomized arrogance of ignorance of 'The Tudors.' Shame on the BBC for producing it." Starkey had even harsher words to say about "The Tudors" when he told The Telegraph, "It's gratuitously awful."

To its credit, the BBC responded by insisting the show wasn't history per se, but "a highly authored and entertaining interpretation of events in a period in history."

Hogan's Heroes

Making its debut on CBS in 1965, "Hogan's Heroes" broke new ground by setting a wacky sitcom within a Nazi POW camp during World War II. Bob Crane — whose 1975 murder remains unsolved — starred as the titular Hogan, a U.S. officer in charge of a group of soldiers imprisoned in Stalag 13, under the control of a German officer, Col. Klink (Werner Klemperer). Right under Klink's nose, Hogan and his men sabotaged the Nazis with all manner of covert schemes. They accomplished this with the aid of a secret system of tunnels beneath their barracks, along with spy periscopes hidden throughout the camp, and a telephone hidden in a coffee pot. They also enjoyed such covert creature comforts such as a steam room and barber shop — none of which would have been remotely realistic in a POW camp.

Beyond those blatant inaccuracies, it was clear that "Hogan's Heroes" was not intended to represent historical record. However, even some of the minor details were wrong. For example, Hogan's men included not just American soldiers, but also members of British and French forces, all sharing the same barracks. In reality, however, prisoners of war would have been housed with others of the same nationality.

Meanwhile, "Hogan's Heroes" French inmate LeBeau was a talented chef who cooked up gourmet meals for the other men, courtesy of food smuggled into the camp — whereas actual prisoners were typically fed potatoes, turnips, and the like.

The White Queen

Based on the historical novels of Philippa Gregory's series "The Cousins' War," "The White Queen" focuses on three women battling to become queen of England during the War of the Roses in the Middle Ages. Elizabeth Woodville — played by Rebecca Ferguson — emerged triumphant, winning the heart of Edward IV and becoming the first commoner to wed a reigning British monarch.

As for the series' historical accuracy, medieval historian Michael Hicks had plenty of gripes to share in an interview with The Guardian, ranging from clothing with noticeable zippers (which were centuries away from being invented) and the fact that the show was very obviously shot in Belgium, not England. Hicks also noted that the chronology of events had been altered — for dramatic effect, of course, and exaggerated Elisabeth's rivalry with the Earl of Warwick. "But Warwick wasn't always her enemy — he presided at her coronation, and the churching (or blessing) after the birth of her eldest daughter," he explained. Regular viewers also noticed these incongruities, taking to social media to point out various historical inaccuracies, ranging from concrete steps with handrails to actors' manicured fingernails. As The Telegraph detailed, they also took issue with some of the language used on the show, including such phrases as "mad for you" and "have it all."

Meanwhile, art historian Andrew E. Larson shared his problem with the series, writing in a blog post, "One major issue is that it starts employing speculation and gossip as fact," he wrote.

Doctor Who

One of the longest-running series in television history, British sci-fi series "Doctor Who" made its debut way back in 1963. At the time, it was originally intended as an educational series that would teach history to British kids via the Doctor's time-traveling TARDIS, which propelled him into the past for adventures set in various historical eras.

As the series grew more popular, those educational aspirations receded while its sci-fi elements expanded. When a story did take place in the past, the show's writers played fast and loose with historical accuracy. That was clear with the revelation that the gods of ancient Egypt were an alien race, the Osirians, to say nothing of an episode in which Queen Victoria founded the Torchwood Institute, a secret government agency charged with protecting Earth from alien and/or supernatural threats. In addiction to that particular monarch, the Doctor has also rubbed elbows with the likes of civil rights icon Rosa Parks , William Shakespeare, Queen Elizabeth I (to whom he was married before making a run for it), and Sir Winston Churchill, among others.

Interestingly, the show's relationship with history has been a mixed bag; that Rosa Parks episode, for example, hewed very close to actual events, as did those involving Agatha Christie and Vincent Van Gogh. Those, however, appear to be exceptions rather than the rule, with historical figures and events used more as reference points in the Doctor's ongoing adventures than as educational subjects.

M*A*S*H

There are myriad reasons why the Korean War was even worse than you may think, many of which were depicted in "M*A*S*H," which followed a group of U.S. Army doctors and nurses during the Korean War as they stitched up wounded soldiers. "M*A*S*H" became an iconic TV hit, airing for 11 years — which, any historian will point out, was eight years longer than the war itself lasted.

While the show promoted a vehemently anti-war message to millions of viewers in the midst of the increasingly unpopular Vietnam War, "M*A*S*H" also took some liberties with its portrayal of the Korean War, particularly with respect to the timeline. That was the case when actor McLean Stevenson exited the show, which resulted in his character, Col. Henry Blake, being replaced by Col. Sherman Potter (Harry Morgan) at the start of the fourth season. The date of Potter's arrival was stated as September 19, 1952; however, the war ended the following July, meaning that the subsequent six seasons took place within a period of a mere 10 months.

"M*A*S*H" has rightfully been lauded for its depiction of performing surgery in a war zone, yet there were some minor discrepancies with historical fact that sharp-eyed viewers could notice. These included aluminum beer cans (which weren't introduced until the late 1950s), Hershey bars with visible UPCs (barcodes, which weren't used until 1974), and an Avengers comic book — which didn't debut until a decade after the war ended.

Outlander

Viewers of "Outlander" — based on the novels of Diana Gabaldon — are well aware that the show's premise is a fanciful one: Claire (Caitriona Balfe) is a nurse who mysteriously travels in time from 1946 to 18th-century Scotland, where she falls in love with Jamie Fraser (Sam Heughan). Beyond the outlandish time-travel premise, there are things "Outlander" gets both right and wrong about history. When it comes to the former, historical accuracy in depicting Scotland during the 1740s was maintained via a consultant, University of Glasgow historian Dr. Tony Pollard.

That said, Pollard has pointed out that the Jacobite Wars, at the center of the "Outlander" storylines, were actually far more complex than depicted on the show. "As ever with history, the reality is a lot more complicated and the edges are blurred," he told British Heritage Travel.

One big historical discrepancy involved Jamie Fraser's tartan. As a member of the highland Clan Fraser of Lovat, Jamie should have been outfitted in a colorful tartan boasting bright red and green; in the show, though, Jamie's tartan is more subdued, consisting of blues and greys. The decision to use those colors came from "Outlander" costume designer Terry Dresbach. "What I did was I tried to put myself in the head of somebody in the 18th century," Dresbach told Elle, explaining that research into the type of plants available to create dyes in that part of Scotland dictated that particular choice of colors.

The Crown

The tragic real-life story of Queen Elizabeth II was dramatized in the lavish Netflix series "The Crown," earning critical acclaim, a huge viewership, and a staggering 24 Emmy Awards (out of 87 nominations). While viewers may have assumed what they were watching depicted actual events, the show's commitment to historical accuracy was woefully lacking. That was evident in the first season, in the sad storyline of Venetia Scott, faithful secretary to Winston Churchill, who is struck by a bus and killed. In actual fact, Venetia did not exist, a fictional creation of the series' writers. Another invention came a few seasons later, when Kate Middleton had an entirely fictional encounter with future husband Prince William when they were youngsters.

Arguably the most egregious use of dramatic licence came in an episode depicting Michael Fagan breaking into Buckingham Palace and sneaking into the queen's bedroom while she slept. In the show, she awakens and calmly listens while he shares his distress about his own life and the state of the country; in actuality, as soon as she realized an intruder was in her room, she immediately called for help.

Despite series creator Peter Morgan's assertions that the show is historical fiction, not fact, historian Hugo Vickers saw that to be a slippery slope. "People actually do believe it because it is well filmed, lavishly produced, well acted with good actors," Vickers told CNN. "Anyone watching, they may say, 'I saw it on "The Crown," it must be true.' It's not true."

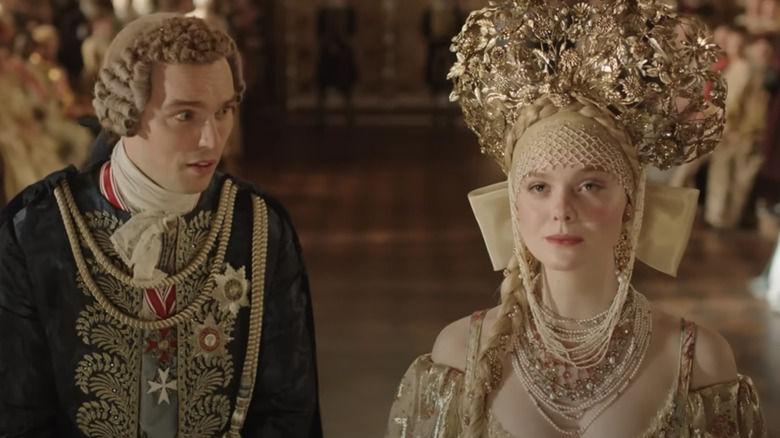

The Great

Airing for just three seasons, "The Great" spoofed the messed-up truth of Catherine the Great (portrayed by Elle Fanning). As a historical comedy prioritizing laughs over historical accuracy, it's not surprising that the show fudged some pretty fundamental facts.

For example, Catherine's husband, Emperor Peter (Nicholas Hoult), is depicted as being the son of Peter the Great, when he was actually his grandson. In the series, Catherine and Peter meet in their late teens, and are immediately married; in reality, they'd known each other since childhood, and their marriage didn't take place until a year or so after Catherine's arrival in Russia. Then there's Peter's habit of carrying around his mother's skeletal remains. In truth, his mother died shortly after his birth, meaning he wouldn't have had the capacity to instruct his courtiers to hang onto her mummified body on his behalf. And of course, there's the coup that deposed Peter and placed Catherine on the throne; while the series has that event happening within the first year of their marriage, in truth Catherine didn't become empress until nearly two decades of matrimony.

Of course, that's all beside the point for series creator Tony McNamara, who shared his vision of modernizing the story of Catherine the Great in an interview with Final Draft: "What if Catherine was in Chicago and she was a 24-year-old woman who just married an idiot and now she had to decide whether to kill him?"

Peaky Blinders

A hit with critics and fans alike, "Peaky Blinders" focuses on a street gang that controlled organized crime in the British city of Birmingham during the 1920s. The Peaky Blinders gang was real, and its members, as in the show, were distinguished by their headwear: peaked newsboy-style caps. What is pure fiction, however, is the show's depiction of gang members sewing razor blades into the brims of the hats, allowing the hats to be used to slash their victims' foreheads and cause blood to gush out, which would temporarily blind them.

While that served as a dramatic plot device for the TV show, did that actually happen? Not according to historian Carl Chinn, who pointed out that razor blades had just been introduced during the 1890s, and were considered a luxury that would have been far too expensive for the gang members. Furthermore, he explained to the Birmingham Mail, a razor-brimmed hat would not have been a very effective weapon. "And any hard man would tell you it would be very difficult to get direction and power with a razor blade sewn into the soft part of a cap," he said.

Chinn also revealed that the show was set a few decades later than it should have, and that gang leader Tommy Shelby (played by Cillian Murphy) is a fictional invention. "There was no real Tommy Shelby and the Peaky Blinders were around in the 1890s, and yet the series is set in the 1920s," he added.

Freud

When first unveiled in 2020, Netflix's crime drama "Freud" received decidedly mixed reviews. While some critics found it to be a solid psychological thriller, there were those who couldn't move past the premise. As a review in The Guardian noted, the drama recasts famed psychologist Sigmund Freud "as a coked-up, seance-enthused witch hunter who uses hypnosis to solve crimes in 19th-century Vienna."

That concept alone would be enough to leave historians fuming (to be clear, there is no record whatsoever of Freud moonlighting as an amateur sleuth). However, it's fair to say that the intention behind the series was never to present an accurate depiction of the father of psychoanalysis, but for Freud to be a jumping-off point for a whodunit. "When you do period dramas or thrillers, you must be very careful they don't look too historical," series creator Marvin Kren told Variety. We want to appeal to young and modern audiences ... you will see modern and provocative elements mixed in with the historical."

Bridgerton

Few historical dramas in recent memory have wormed their way into the pop-culture consciousness as successfully as "Bridgerton." Produced by "Grey's Anatomy" and "Scandal" creator Shonda Rhimes, the series — based on a popular series of novels — reimagines Regency-era Britain. Some actual historical figures are thrown into the mix, including Queen Charlotte and her mentally unstable husband, King George III, who came to be known as the "mad king."

"Bridgerton" is somewhat unique among costume dramas in that it hews close to historical fact, while also deliberately taking some big leaps in terms of casting actors of various races when the aristocracy of that era would have been predominantly white. "It draws on what we know to be historical reality," the show's historical adviser, Hannah Greig, told History Extra, "but also asks the audience to think more carefully about their expectations of what a period drama should look like, and also what it might be like if history was slightly different."

One aspect of the show that's heavily fictionalized is the notion that a woman of aristocratic stature would marry solely for love. "In those social classes, the idea of a love match was not primary ..." history professor Michael Peplar told Northeastern Global News. "These were often marriages made for dynastic reasons than for reasons of personal fulfillment."

The Borgias

Debuting in 2011, "The Borgias" focused on one of history's most devious families, led by a man who was arguably the most wicked pope to ever reside in the Vatican: Rodrigo Borgia (played by Jeremy Irons), also known as Pope Alexander VI. So scandalous was his tenure as pontiff — from 1492 until 1503 — that his living quarters were sealed off by his successor, remaining so for centuries.

The legend of the Borgias' villainy has expanded over those years, and "Borgias" creator Neil Jordan depicts the family as a sort of 15th-century equivalent of the Sopranos; a crime family steeped in crime, corruption, illicit sex, and murder. Of course, historians will point out that the Borgia family's notoriety has been enhanced by rumor and embellishment, much of it coming from the family's enemies.

Not surprisingly, Jordan leaned into the legend for dramatic effect, trampling over historical accuracy. "I don't claim to be telling a completely factual tale; that's for textbooks," Jordan said, via Reuters. "This is a suspenseful crime drama based on real characters and events. I have a rapacious thirst for historical material and if something sets off my imagination, I use it."