Why The Battle Of Gettysburg Was Worse Than You Thought

The battle of Gettysburg, fought from July 1-3, 1863, in rural southern Pennsylvania, was both chronologically and emotionally close to the midpoint of the U.S. Civil War. Occurring a little over two years after the conflict began, the Confederate defeat meant that their planned invasion of the North and hopes of replenishing supplies from yet-unravaged Yankee farmland had failed. Union cities were safe from Confederate advances, and with only a few exceptions, after Gettysburg, Southern armies did not present serious threats to Union territory. It would take nearly another two years to die, but the Confederacy left the battlefield mortally wounded.

As a critical moment in the United States' most romanticized war, Gettysburg is one of the most famous battles in American history. It was also one of the most excruciating for its participants, with thousands dead and tens of thousands wounded after three sweltering days in the Pennsylvania sun.

It was the bloodiest battle of the Civil War

Depending on how you count, Gettysburg was the bloodiest battle of the Civil War. It admittedly carries an asterisk since it took place over three days, which, to put it crudely, gave Gettysburg fighters more time to run up the score. The Battle of Antietam, fought on September 17, 1862, in Maryland, is the bloodiest single-day battle in American history with nearly 23,000 casualties, among them over 3,600 dead.

The total casualty figures for Gettysburg are eye-popping: Of over 165,000 combined men, 51,112 would become casualties, and over 7,000 of these would die there in the Pennsylvania farm country, figures that are roughly twice the terrible toll of Antietam. Most of the Union servicemen who died during the battle are buried nearby in Gettysburg National Cemetery, a project spearheaded by local people who were faced with the grim and enormous task of burying the corpses that lay strewn about the battlefield. (The local people buried the Confederate dead as well, but these remains were eventually relocated to the South.) It was at the dedication of the cemetery, several months after the battle, that Lincoln gave the famous Gettysburg Address.

Union General Meade failed to follow up on the victory

Armchair generals sometimes criticize the Union's Major General George Meade for failing to pursue Robert E. Lee's battered army as it limped south from Gettysburg. (He did follow them for a while, but he didn't chase them all the way back into Virginia.) Had Meade swooped after the Confederates, he might have captured them or forced another battle to weaken them further. Indeed, it could be speculated that Lee could have been captured, depriving Confederate forces in the east of their most prominent commander. Meade's decision not to go after the retreating army looks at first glance like a failure, a lost chance to kneecap the "Lost Cause."

Others have argued that a pursuit by Meade would have been foolish. He'd been in charge of his army for a mere week before Gettysburg and didn't know his force inside and out as Lee knew his, having fought at the head of his army for over two years. Furthermore, just because the Union army won the battle didn't mean the Federal force wasn't badly damaged from the fighting. Meade had lost men and, crucially, subcommanders. His men had fought for three days and were close to the limit of human endurance. And the weather was terrible. And he would be pursuing the Confederates into Southern or Southern-sympathizing territory in Maryland and Virginia.

Meade also had no way of knowing how badly beaten up the Southern force was, but he did know Lee was famous for setting up strong defensive positions. A pursuit under these circumstances was not guaranteed to succeed, and a Union loss might have left Pennsylvania undefended.

The Confederate Army faced a miserable 10-day retreat

The Union army's decision not to pursue them as hard as possible was one of the very few good things to happen to the Confederates as they slinked back toward friendly territory. The Confederate wagon train, chock-full of wounded and dying men, stretched an unwieldy 17 miles. Ferocious rain soaked clothing and made the roads muddy morasses, all while swelling the Potomac River that the haggard force would soon have to cross. And while Meade would ultimately not dive in for the kill, the Confederates were not yet sure of this reprieve. Furthermore, there was an actual mountain the Confederates had to climb in order to even make it to the river crossing.

It got worse. A Union detachment under a particularly brash general captured some of the Confederate wagons and wounded. Angry pro-Union saboteurs hacked at wagon wheels in the night. The bridge the Confederates planned to cross had been destroyed by Union forces. And even though the main force of the Union army didn't descend on the hammered Confederates, low-level cavalry scraps kept them on their toes the whole time. Finally, on the night of July 13, the Potomac receded enough that the miserable Southern army could slosh across it to safety — or as much safety as there was to be had during the ongoing war.

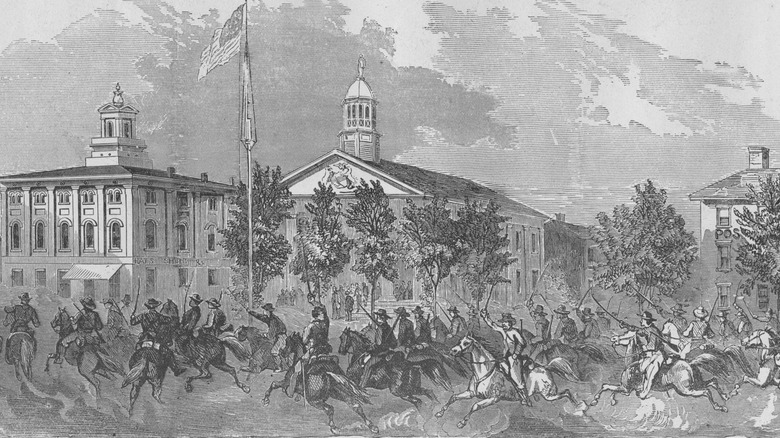

It didn't keep the Confederates out of Pennsylvania for good

While the failure at Vicksburg meant that the South would not mount another full-scale invasion of Pennsylvania, it didn't mean that the Keystone State would remain free of harassment by rebel forces. Just over a year after Gettysburg, as fighting in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia grew more and more savage, Confederate leader Lieutenant General Jubal Early sent a small detachment north to scare the Union and try to snag some supplies.

The target was Chambersburg, a town in southern Pennsylvania about 25 miles west-northwest of Gettysburg. The Confederate raiders were instructed to demand a ransom in cash or gold for the town, and if it wasn't paid, they were to torch Chambersburg. Confederate commander John McCausland slipped past a distracted and overextended Union force and arrived at Chambersburg in the very early morning of July 29th. After a day of looting and harassing the residents, McCausland ordered the town burned and the courthouse demolished, destroying 550 buildings and leaving some 2,000 residents of Chambersburg homeless. As an added insult, the Confederate raiding force successfully escaped back to Confederate territory, even taking about 80 Union captives on their way.

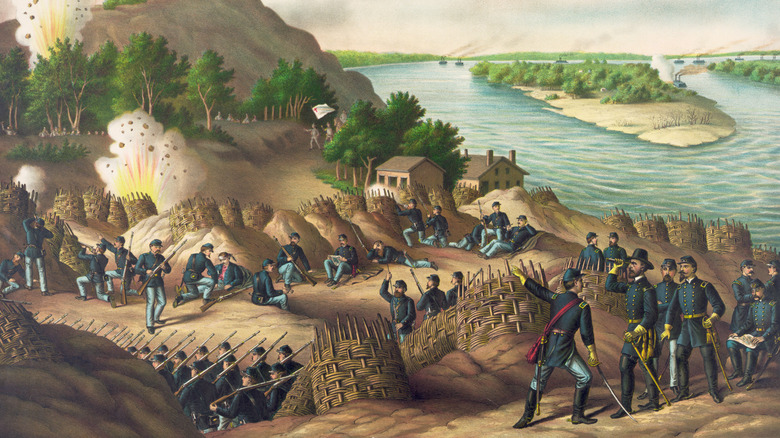

The battle coincided with the fall of Vicksburg

If you'd bet on the South to win the war, by July 1863, you were looking for a way to weasel out of that wager. Almost perfectly aligned with the disaster in the east, the Confederates faced another morale-shattering loss with the fall of the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, after a pummeling 47-day siege.

Navigation on the Mississippi River was crucial to Confederate infrastructure, even after the South bobbled away its biggest city and best port by allowing New Orleans to be captured early in the war. By mid-1863, Union successes meant that Confederate control of any part of the river hinged on two sites: the city of Vicksburg and the smaller fortifications at Port Hudson, Louisiana. If these Confederate strongholds fell, not only would the Confederacy lose use of the river, but it would also cut the rebel territory in two.

Led by none other than Ulysses S. Grant, the Union army relentlessly hammered Vicksburg from late May, 1863. By early July, with Vicksburg residents having fled to caves in the bluffs over the river in search of safety from Union bombardment, Confederate forces agreed to abandon the town. They marched out and left Grant in possession of the key site on July 4. Port Hudson surrendered soon after they heard of the fall of Vicksburg, and the Mississippi was again a Union waterway.

Pickett's Charge was a terrible slaughter

By the afternoon of July 3, Robert E. Lee knew he was running out of opportunities to win at Gettysburg. He had a handful of fresh troops under the command of General George Pickett, who had also happened to graduate dead last in his class at West Point. It was Pickett and his boys or nothing, though, and Lee sent them against the center of the Union position.

Pickett's Charge is remembered by some as representing the high-water mark of the Confederacy. To soften up the Union position, Pickett ordered an hour-long artillery barrage before urging his men forward to win one for Virginia. However, the Union guns had survived the barrage, and while some Confederate forces, at enormous cost, managed to approach the Union lines closely enough to fight at close quarters with Union soldiers, they failed to break through, much less turn the tide of the battle.

Over 6,000 men that the Confederacy could ill afford to lose were killed, wounded, or captured — more than half the personnel involved in the charge — and the alleged gallantry of Pickett and his men went on to become a cornerstone of the Lost Cause in the years following the war.

The wounded faced primitive battlefield care

At the end of the Battle of Gettysburg, in addition to the 7,000-plus men killed, over 20,000 lay wounded. Civil War-era battlefield medicine, though carried out by dedicated doctors, nurses, and servicemen, fell far short of the expectations modern people have for emergency care, even as these workers' experiences helped drive medical advancements. In 1860, there were 113 doctors in the U.S.'s small peacetime army; by war's end, the Union forces had over 12,000 and the Confederacy 3,000.

The soft lead bullets commonly used by both armies flattened when they hit, causing severe tissue damage and often drawing contaminated clothing into wounds as potential sources of infection; this wasn't necessarily clear to the wounded or to those caring for them, given that germ theory was not yet the consensus position. (Nurses did know to wash their hands.) Three out of every four Union surgical operations were amputations, and even though only senior doctors carried out the procedure, they were fatal in a little over a quarter of cases, with survival more likely the further away from the trunk the cut line was. Anesthesia was used when available, though it did not yet provide total unconsciousness, and 43 deaths are recorded from its complications.

While surviving Union records are better than Southern ones, Mississippi's post-war budget offers one of the most shocking statistics. In 1866, the state spent 20% of its funds on prostheses.

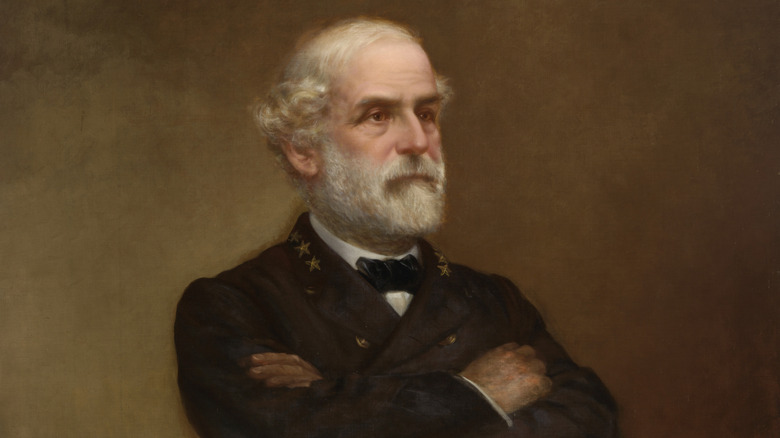

Robert E. Lee may have been recovering from a heart attack

It's hard to think of Robert E. Lee as the real victim of the Battle of Gettysburg. It was, broadly speaking, his idea, and he did survive it, unlike many other men who took the field during the fight. Some commentators have looked for a potential explanation for Lee ordering Pickett's Charge, beyond the simple one of desperation, and have argued that the general was still recovering from a recent heart attack.

Lee had been sick in the spring of 1863, and his complexion had apparently dulled, giving him a gray cast. It wouldn't be surprising if a man fighting a war in his 50s didn't look or feel great, but victims often report mistaking heart attack symptoms for those of the flu. In March and April, he reported sharp chest, back, and arm pain, and Confederate doctors diagnosed him with "pericarditis," inflammation of the sac containing the heart, in April.

It didn't slow him down enormously, though: Lee defeated a Union force at Chancellorsville in late April and spent May and June galloping around the Eastern Theater. Whether he had a heart attack or not (which we can't know), it wouldn't explain his decisions at Gettysburg.

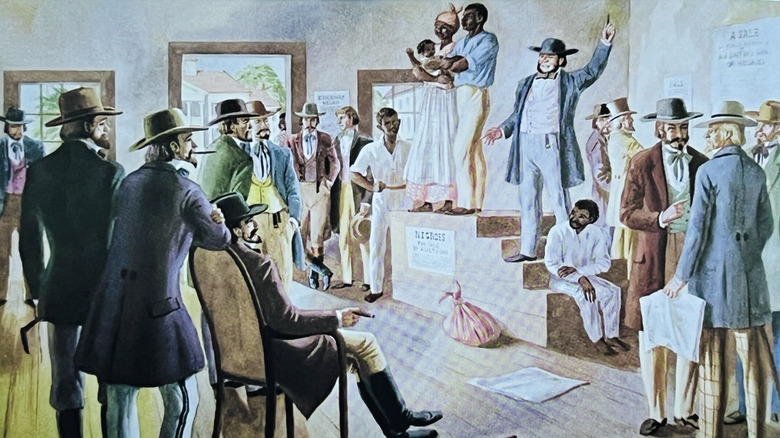

The Confederate Army captured Black people to sell into enslavement when they returned to Virginia

The argument that the Civil War wasn't really about slavery would have been news to many of the participants. Pennsylvania, a free state, was an attractive destination for enslaved people in Virginia once the war began, and the Keystone State also hosted a free Black population. These groups were deliberately targeted, along with some of their counterparts in Maryland, by the advancing Confederate army during the Gettysburg campaign. Despite their loss, the Confederates were still able to abduct a number of these people and transport them into Confederate territory for sale into enslavemnt or return to their former enslavers.

Confederate forces had already begun forcing enslaved people further south to keep them away from Union forces that might liberate them. Meanwhile, the Confederate congress had formally demanded revenge against the Federals for having armed Black soldiers — the inversion of authority was simply intolerable to them. In this context, and given the existing attitude among Southern decision-makers that Black people were simply tools or assets, no Black person they encountered would be safe. Figures for the number of people abducted by the army and carried with it even as it fled the battlefield do not exist, but may be as high as 1,000.

It was dangerously hot

It probably won't amaze you that July before air conditioning was a warm and sticky affair, but the heat wave that greeted the armies in the runup to Gettysburg was so dangerous that men were reportedly falling over dead from the strain of having marched to the battle. By 2 p.m. on July 3, shortly before Pickett's Charge, the temperature had spiked to a scorching 87 degrees Fahrenheit in the shade, with nary a cooler full of beer and soft drinks in sight.

Humidity makes it harder for the human body to cool itself, as sweat doesn't evaporate as readily in already "wet" air. Humidity levels for the battle itself don't exist, but the heat index was probably 10 or so degrees hotter, pushing the temperature into dangerous territory. Past about 90 degrees on the heat index, people exerting themselves are at risk of heat stroke or muscle cramps. As an additional torment, the sun was out for at least part of the battle, shining into unprotected eyes and searing any exposed fair skin.

Now consider that most of the soldiers fighting at Gettysburg were wearing wool uniforms, and many of them would have been wearing long underwear underneath them. Additionally, Gettysburg came after some heavy marching by both armies — no one involved was well rested, and many may already have been somewhat dehydrated.

Nine people died during the 50-year reunion

In 1913, both Union and Confederate veterans descended on Gettysburg for a reunion. Totals are hard to come by, but at least 50,000 men attended some or all of the multi-day event, aided by Boy Scouts and lodged in tent complexes erected by the Department of War. The total quota of dead of Gettysburg had, apparently, not quite been filled, as nine participants died during the festivities.

A few deaths were not especially surprising, as even the absolute youngest of the men would have been in their mid-to-late 60s, with an average age of 72. The temperature was even higher at the reunion than it had been at the battle, topping 100 degrees Fahrenheit as the old soldiers reminisced. Of the nine veterans to die during the reunion, five died of cardiovascular events, one of the heat, one of kidney disease, one of "exhaustion," and one of "asthenia," an old-fashioned term for weakness and/or fatigue.

The experience of the 1913 reunion didn't dissuade planners. In 1938, 1845 Civil War veterans from both armies, but not limited to survivors of Gettysburg, met at the battlefield for a final commemoration.