Inside The Biggest White House Scandals Of All Time

Only 45 men have served as president of the United States. Some of the most chaotic elections in history have delivered the country its leader, most of them via a plurality of cast votes and also through the sometimes problematic Electoral College. Generally the standard-bearer of one of the two major political parties of any given era, every president has struggled under the weight of what's one of the toughest jobs in the world. As such, and as hailed as many of them are by their supporters at first and historians later, every president is a flawed human being with their own personal and political interests coming into play. Throw in some aggressive opposition and the lure of filthy lucre and corruption, and that makes for a near-universal fact: Just about every president has faced some kind of scandal while in office.

Respected politicians can also be terrible people, and allegations can lead to some of the biggest lies American presidents ever told, as well as downfall and disgrace if the events are particularly egregious and horrific. Here are the biggest and notorious scandals to ever mar the office of the American presidency and those who governed from the Oval Office.

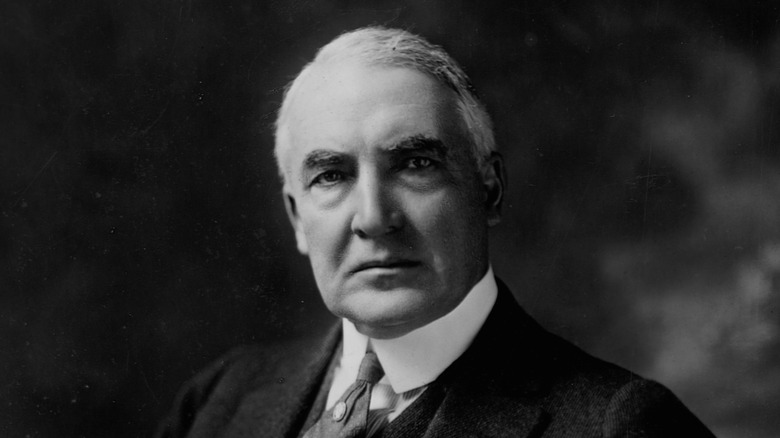

Warren G. Harding and Teapot Dome

Back in the 1910s, the federal government earmarked oil reserves — one in Wyoming and two in California — for the Navy to power its ships. In 1921, the recently inaugurated Warren G. Harding appointed Senator Albert B. Fall to the role of secretary of the interior. Fall then quickly convinced Harding to sign over control of the Navy's oil fields to the Department of the Interior via an executive order.

Secretary Fall then entertained offers from representatives of two of the country's biggest oil companies, Sinclair Oil and Pan-American Oil. Both were given contracts that enabled them to access two of the three previously Navy-only areas, Elk Hills in California and Teapot Dome in Wyoming, so named for its characteristic natural rock formation. All of the arrangements had been made in secret, albeit with Harding's approval, but when privately held oil companies set up shop on government land, a group of U.S. senators was incensed over what appeared to be corruption and special deals, as no one besides Sinclair and Pan-American had been allowed to place bids.

The Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys looked into the matter and found that Fall had accepted large bribes — in excess of $400,000 in cash and bonds — from the oil companies in exchange for the right to drill. By the time the full scope of the "Teapot Dome" came to light, Harding had died and Fall had resigned his post.

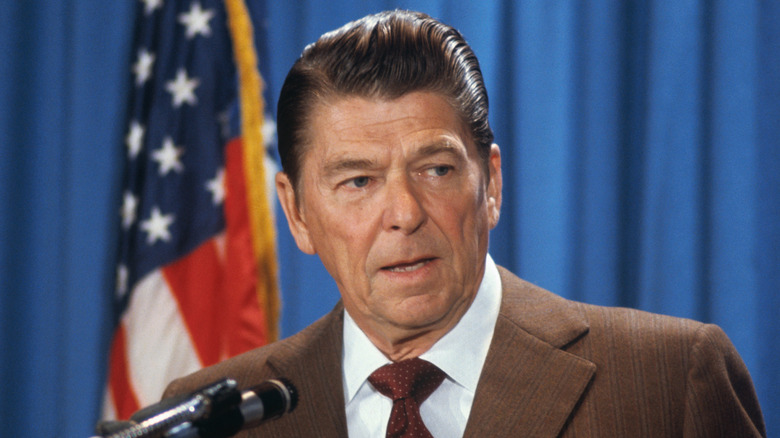

Ronald Reagan was involved in the Iran-Contra deals

At the height of the Cold War, President Ronald Reagan held such virulent anti-communist sentiments that his administration supported covert efforts to destabilize such governments around the world. Under a covert plan called the Reagan Doctrine, the Central Intelligence Agency trained, funded, and armed rebel groups around the globe that shared Reagan's philosophy. Unable to get above-board funding because the Democratic Party controlled Congress in the 1980s, Reagan and his Republican cohort had to get the money elsewhere, and through illegal and quasi-legal means.

"I want you to do whatever you have to do to help these people keep body and soul together," Reagan reportedly told National Security Adviser Robert McFarlane (via American Experience) in 1984 regarding Contra, a right-wing group seeking to oust Nicaragua's communist-aligned government. In 1985, Iran asked to buy weapons from the U.S. government to assist in its war with Iraq. Believing that negotiating with Iran could help free American hostages in Lebanon, Reagan approved the sale, even though that nation was currently under a trade embargo with the U.S.

After more than 1,500 missiles were sold to Iran, and a Lebanese newspaper exposed the transactions in 1986, President Reagan appeared on television and denied everything. Later that year, the military of Nicaragua downed a plane that turned out to be loaded with American weapons bound for Contra, which had already received funding from the U.S. — generated by the sale of arms to Iran.

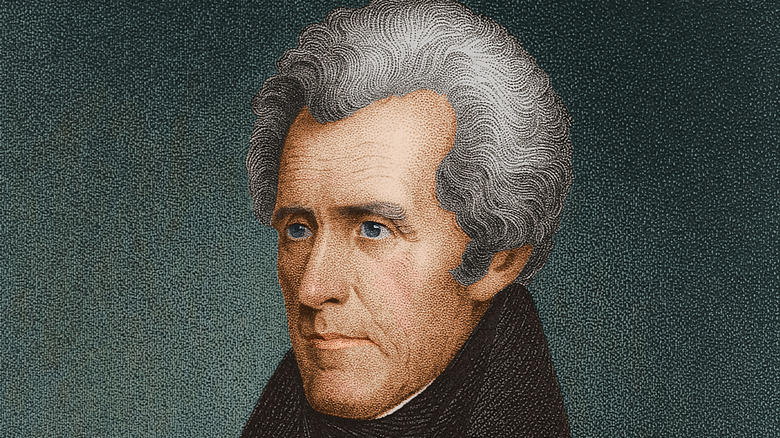

The Petticoat Affair embroiled Andrew Jackson

In 1829, President Andrew Jackson appointed John Eaton to the position of secretary of war. Eaton had recently married the former Peggy Timberlake, whose first husband, Eaton's close friend Senator John Timberlake, had died of pneumonia nine months prior. Nasty rumors hit the D.C. social scene, suggesting that the Eatons' relationship began as an affair, prompting Sen. Timberlake to die by suicide. Eaton was also declared completely unacceptable by Washington's high society ladies: She was seen as uncouth and impure, having often spoken to men whilst serving at her father's pub as a young woman.

Floride Calhoun, wife of Vice President John C. Calhoun, ensured that the Eatons weren't welcome in Washington's elite homes and at social events. President Jackson had to publicly speak his support for the Eatons, but then his first lady and official White House hostess — his late wife's niece, Emily Donelson — joined the anti-Eaton brigade. Jackson fired her in favor of his daughter-in-law, Sarah Yorke Jackson. After Vice President Calhoun squared off with Jackson on tariffs and states refusing to abide by federal laws, the president called out his number-two for using the Eatons' rejection to gain political capital with an aim toward stealing the presidency.

The whole thing was so embarrassing that John Eaton and Secretary of State Martin Van Buren resigned their cabinet positions. Jackson dismissed all the others, whose wives had all had a hand in the public discrediting of the Eatons.

Bill Clinton had an affair and lied about it

In 1994, the Washington, D.C., district court hired Kenneth Starr to serve as the independent counsel in an ongoing investigation into President Bill Clinton, following allegations of financial impropriety in the years before he was elected president in 1992. Then in 1997, attorneys representing Paula Jones in a sexual harassment lawsuit against Clinton learned that an intern, who'd worked at the White House in 1995, had possibly engaged in an affair with the president. That intern, Monica Lewinsky, was subpoenaed, and she swore in an affidavit in January 1998 that no physical relationship had ever taken place. Days later, Lewinsky's former coworker, Linda Tripp, told Starr's office that she had audio recordings of Lewinsky discussing her encounters with Clinton.

Authorities offered Lewinsky legal immunity if she testified against Clinton. She then admitted that the relationship had happened, while Clinton had denied it in another deposition. That constituted lying under oath and obstruction of justice in the Jones case, both impeachable crimes according to Starr in a report to the House Judiciary Committee. In December 1998, the U.S. House impeached President Clinton, but the Senate didn't acquire the votes necessary to convict and expel.

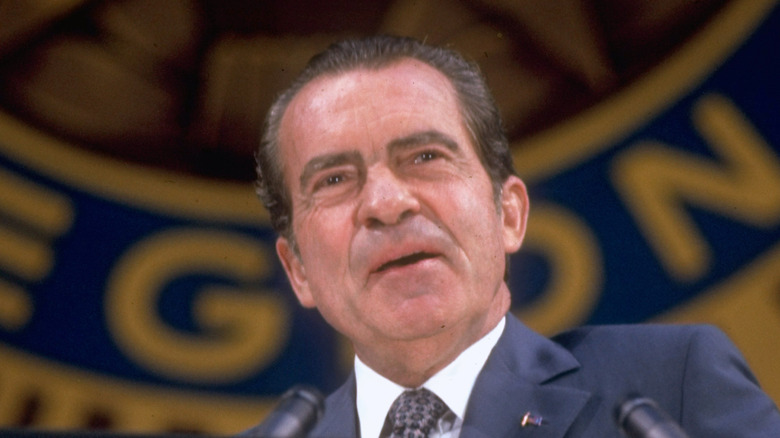

Richard Nixon was linked to the Watergate break-in

In 1971, major newspapers published the "Pentagon Papers," damning government documents about the Vietnam War. An incensed President Richard Nixon put together a team of former CIA and FBI workers and sent them to steal embarrassing information from the psychiatrist treating Daniel Ellsberg, the defense analyst who'd leaked the documents. Some members of that team, working for Nixon's Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP) and under Attorney General John Mitchell, broke into the Democratic National Committee's office at the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C., in May 1972 to bug phones. A month later, those figures were arrested in another burglary attempt of the DNC headquarters.

Tipped off by an insider code-named "Deep Throat" (FBI Assistant Director Mark Felt), The Washington Post reported on Nixon's connections to the crimes, such as a check from CREEP in a Watergate burglar's account, and Mitchell's program that funded anti-Democrat information gathering. The Senate's Watergate investigation exposed Nixon's use of a system that recorded all of his phone calls and conversations across his various offices. The president wouldn't immediately give over his recordings, likely full of incriminating evidence, to special prosecutor Archibald Cox, whom he had fired. In March 1974, seven presidential aides were indicted, with Nixon named as an uncharged co-conspirator. Two months later, the House Judiciary Committee began impeachment filings, but in August 1974, Nixon resigned the presidency.

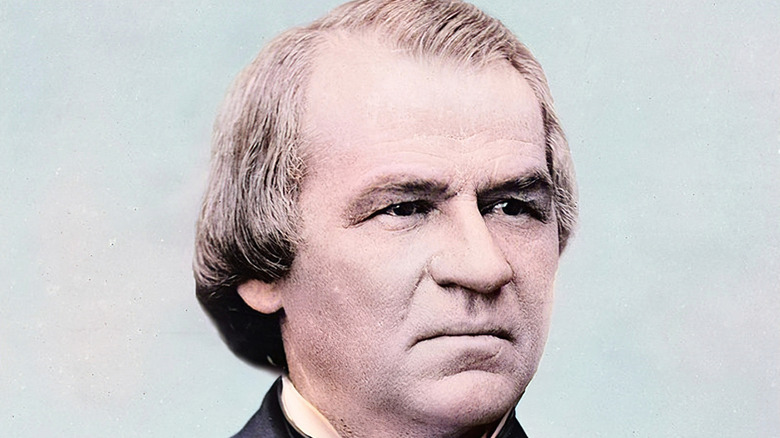

Andrew Johnson was impeached

When President Abraham Lincoln ran for re-election in 1864, the progressive northern Republicans dumped Vice President Hannibal Hamlin in favor of conservative Tennessee governor Andrew Johnson as a means to drum up Southern support, as well as to present a united front for when the war wrapped up and beyond. When Lincoln was assassinated in 1865, the post-war Reconstruction efforts fell to the new President Johnson. He remained loyal to the Southern cause and anti-Black prejudices, however, and with Congress out of session for the initial eight months of his administration, Johnson eased up on a bevy of new laws that would have integrated and enfranchised Black people in the South. Johnson let local governments set up systemically racist and segregationist practices while also issuing thousands of pardons to Southerners arrested and convicted of treasonous efforts during the Civil War.

When Congress got back to work in 1866, it passed constitutional amendments to guarantee the rights of all Americans regardless of skin color, bills to provide aid to and to protect freed enslaved people, and the Tenure of Office Act, which denied Johnson the ability to fire federal employees without getting the go-ahead from the U.S. Senate. Johnson tested the law by firing Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, and in February 1868, the House of Representatives overwhelmingly voted to impeach Johnson, 126 to 47. He avoided conviction by the Senate by a single vote.

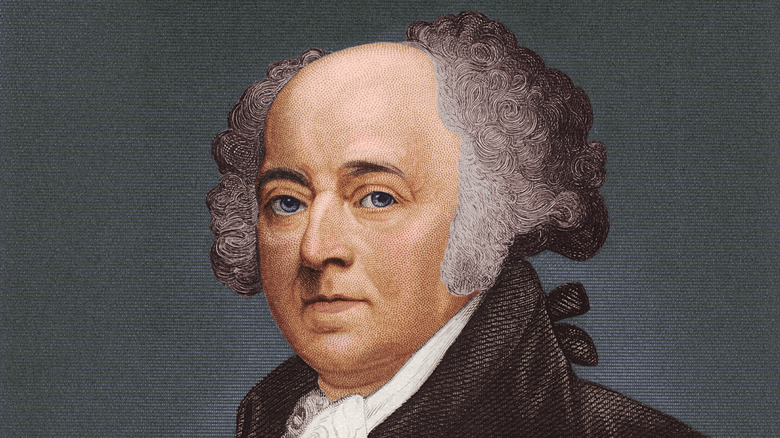

John Adams and the XYZ affair

In the 1790s, the just-formed United States got in the middle of a conflict between Great Britain and France, its Revolutionary War opposition and ally, respectively. It all began with a treaty between the U.S. and Great Britain in 1794 that gave the new nations a tenuous peace. France opposed the treaty, alleging that it violated multiple binding agreements that it had signed with the U.S. In retaliation, France seized several U.S. cargo ships. The situation escalated during the single term of President John Adams. After France failed to accept President George Washington's appointed diplomat in 1796, the newly inaugurated Adams sent a three-man negotiating team in 1797. Once again, French foreign minister Charles de Talleyrand wouldn't meet with the Americans, but said he would in exchange for a large intergovernmental loan and a personal bribe.

When the U.S. Congress heard about the impasse, it aimed to declare war on France and wanted the names of Adams' diplomats. The president refused to identify them, and their names were redacted in his reports in favor of the code names X, Y, and Z. Congress then formed the Department of the Navy and funded the building of warships, all of which went into the July 1798 sea-based attack on French ships. War was never declared, and the Quasi-War, fought over the XYZ Affair, ended after a treaty was ratified three years later.

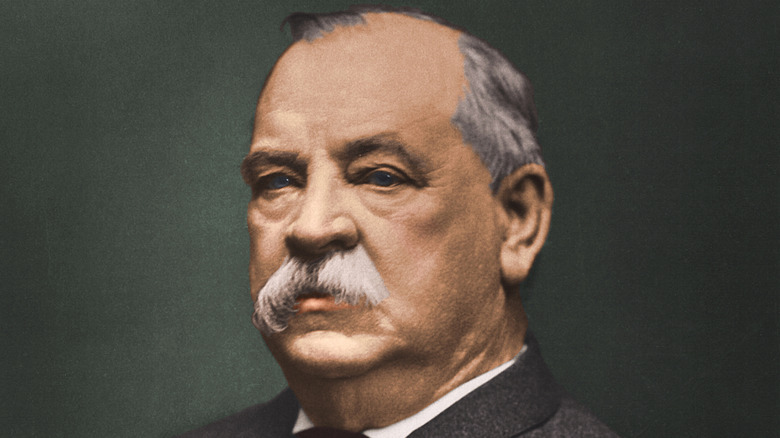

Grover Cleveland, Maria Haplin, and a baby

New York Governor Grover Cleveland won his first of two nonconsecutive elections in 1884 despite an ugly scandal. In 1874, a time in history when physical relationships outside the confines of a marriage were very much frowned upon, Cleveland had engaged in an affair with a Buffalo woman named Maria Halpin. The tryst produced a son, born with the last name Cleveland and who was subsequently adopted, while Halpin was sent to a mental health institution.

When the story broke nationally in July 1884, representatives from Cleveland's campaign confirmed several details, but explained that it happened because the politician hadn't been married at the time and that Halpin was well known around Buffalo as being promiscuous. Cleveland, as the only bachelor who'd been intimate with Halpin, claimed paternity (even though he wasn't sure if he actually was the biological father) and helped in the adoption process.

However, that's not exactly how it went down, at least according to Halpin in a new interview and in an 1874 affidavit. She testified that Cleveland had been attempting to woo her for some time, and after she consented to a dinner, he followed her home, assaulted her, and threatened to ruin her life if she were to report the crime. When a child was born, he was forcibly taken away from Halpin and she was institutionalized. On the campaign trail, rivals taunted Cleveland with the slogan, "Ma, Ma, where's my pa?"

Donald Trump was impeached twice

In 2019, President Donald Trump became only the third president to endure the impeachment process. When a president is impeached, they stand for a trial of sorts, which can lead to expulsion from office. The U.S. House levied two articles of impeachment: abuse of power and obstruction of Congress, alleging that he had sought out assistance from a foreign power to help him retain his office, and then actively blocked attempts by officials to carry out an investigation. The U.S. Senate, controlled by Trump's Republican Party, acquitted the president of both charges.

Two years later, Trump became the first president impeached twice. On January 6, 2021, when Congress was in session to certify the results of the 2020 presidential election, in which Trump was defeated in the complicated Electoral College, the still-sitting president held a rally outside the White House. That then led to hundreds of attendees violently descending on the Capitol building with an aim to stop the votes from being counted. Members of Congress fled and hid, and five people died in skirmishes. Charged with incitement of an insurrection, the Senate declined to convict Trump.

Ulysses S. Grant and the Whiskey Ring

Civil War general Ulysses S. Grant was elected president of the United States in 1868, and his administration was beset with bribery scandals. His close associates, tycoon investors Jim Fisk and Jay Gould, used fraud and bribes to prevent a takeover of their Erie Railroad, and their attempt to take over the gold market led to an industry collapse and financial crisis in 1869, after they convinced Grant to back away from a gold-based economic improvement plan.

Civil War-era taxes on alcohol remained in effect during Grant's administration. They were so high that Midwestern alcohol makers found it was cheaper to not pay and to bribe tax collectors instead. Leaders from Grant's Republican Party wanted in on that lucrative scheme, and in 1871 they formed what was on the surface a fundraising organization for 1872 election candidates, but which was really a bribe-collecting mechanism called the Whiskey Ring. Each member — which also involved distillery, IRS, and Treasury employees — managed to siphon an average of $60,000 (the modern-day equivalent of $1.2 million) each. The leader of the operation was General John McDonald, a friend of President Grant and the appointed head of the IRS's tax collection department. His second-in-command was Grant's personal assistant, Orville Babcock.

After Treasury Secretary William Richardson resigned over a different tax scandal in 1874, his replacement, Benjamin Bristow, discovered the Whiskey Ring and broke it up, with more than 300 individuals arrested, many of them closely linked to the president.

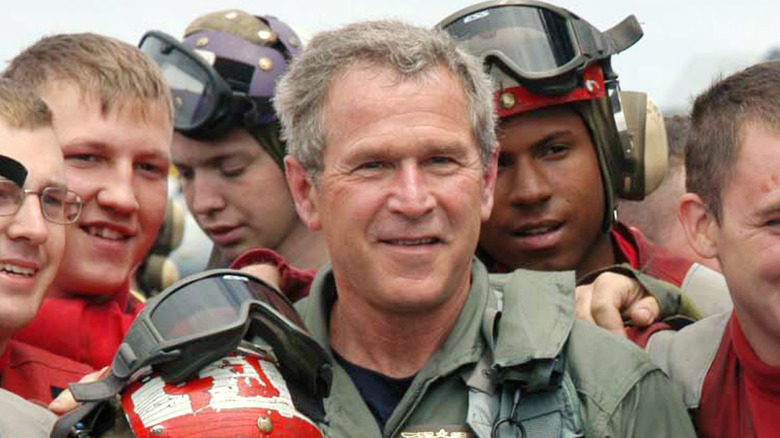

George W. Bush went to Iraq looking for weapons of mass destruction

In August 2001, President George W. Bush was given a classified briefing called "Bin Laden Determined to Strike in U.S." It detailed how al-Qaeda terrorist leader Osama bin Laden was planning stateside revenge for late '90s American attacks on Afghanistan. On Sept. 11, 2001, planes hijacked by bin Laden's forces were flown into the Pentagon, a Pennsylvania field, and both towers of the World Trade Center in New York. As part of the political and military response, the U.S. deployed troops to Afghanistan to locate and punish bin Laden.

While that occupation and war raged, the Bush administration turned its focus to Iraq and Saddam Hussein, suggesting a connection for responsibility for the events of 9/11. No such link was ever firmly established, but the Bush administration insisted that Hussein was building a stockpile of what it called weapons of mass destruction, and military intervention was required. After an impassioned speech from Secretary of State Colin Powell to the United Nations' Security Council, the U.S.-led coalition invaded Iraq in March 2003.

With tremendous military firepower unleashed, President Bush participated in an address from the USS Abraham Lincoln aircraft carrier on May 1, and while dressed in a flight suit, stood in front of a banner marked "Mission Accomplished," implying that the war was over and had been successful. No weapons of mass destruction have ever been found, while Hussein was captured, tried, and executed.