The Biggest Lies American Presidents Ever Told

Politicians often make campaign promises (or even just regular promises) that they cannot possibly keep. In fact, the 11th president of the United States, James K. Polk, is generally known for accomplishing every major policy decision he set out to finish, says the Miller Center, and then skedaddling off to Tennessee, where he died some 100 days after the last day of his first and only term. (And now you can tell your friends you actually know something about Polk)

On the other hand, other than Polk, that leaves 45 other U.S. presidents who didn't complete all their goals. And on top of that, sometimes they lied while in office. U.S. presidents lied for multiple reasons — covering up something illegal, averting major disaster, some reason only they could understand, protecting America's secrets, and the list goes on. Unfortunately, some presidents got into situations that they didn't see a rational way to get out of, which led to the lies.

Even if they were presidents, these men were still human, and humans make mistakes. However, not every lie was a mistake. A couple were actually for the good of the country. Therefore, let's take a look at some of the biggest lies ever told by American presidents.

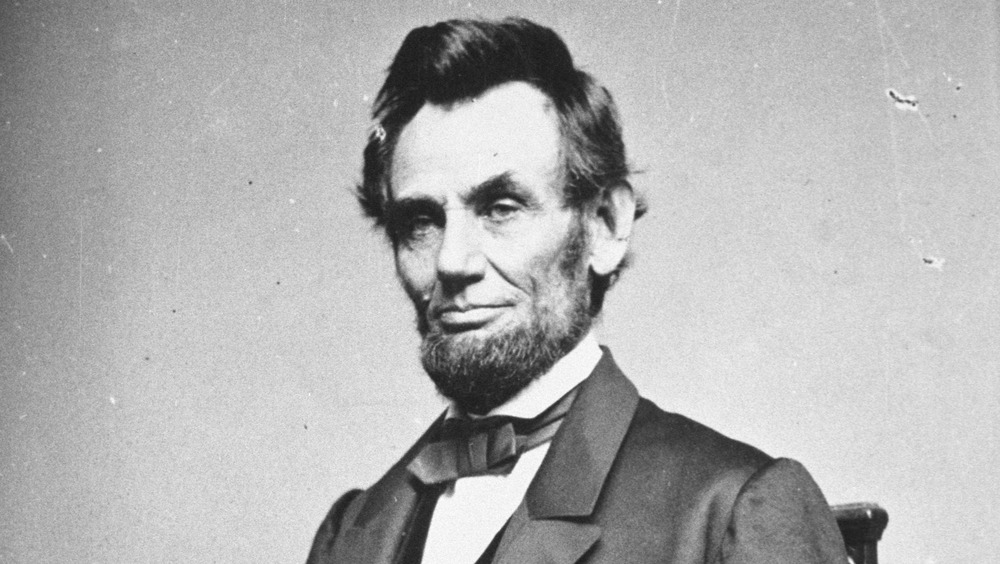

Abraham Lincoln

In 1865, Democrats were wavering over whether to support President Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation due to rumors of peace talks between the president and the Confederates, writes William C. Harris in a piece for the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. Radical Republicans worried that the issue of emancipation would be abandoned if Lincoln compromised with the Confederate president Jefferson Davis in the interest of ending the war. The Civil War had been raging for nearly four years, and hundreds of thousands were dead, according to History.

Before the 13th Amendment vote on January 31, Lincoln received a note from Republican congressman James Ashley informing him of Republican fears regarding peace negotiations, and Lincoln wrote a note to the Republicans explaining that there were no "peace commissioners" in the city. In reality, 73-year-old politician Francis Preston Blair, the most important organizer of the peace talks, had been working since the previous December to find a way for the two parties to meet.

Though the Hampton Roads Peace Conference (which convened at the beginning of February) ultimately failed, the 13th Amendment passed largely due to the president's message, Ashley wrote later. It was one of Lincoln's great achievements during his presidency. The American Civil War effectively ended that April with the Battle of Appomattox Court House. Unfortunately, Lincoln was assassinated just a few days after Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered.

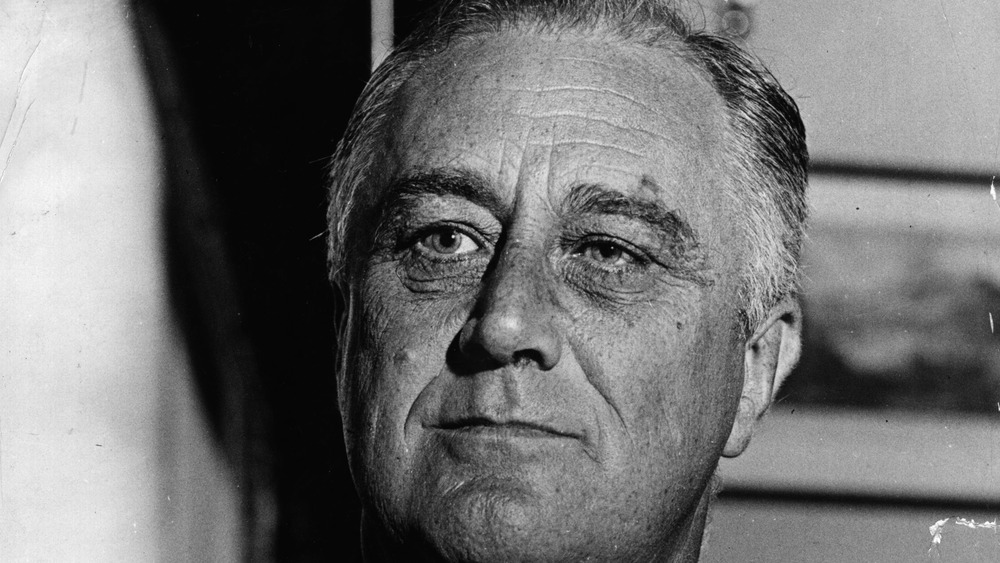

Franklin D. Roosevelt

In 1940, America was impartial to the war brewing in Europe, while President Franklin D. Roosevelt was running for a third term. Though Adolf Hitler had invaded Poland in 1939, America's involvement in the war didn't start until the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941 (via History).

According to Warfare History Network, though Roosevelt assured the country in his fireside chats that America wouldn't send its young men to war, he was actually corresponding with Prime Minister Winston Churchill, setting up America to fight against Germany alongside Britain. Roosevelt committed outdated naval destroyers to the British, referring to Churchill as "Former Naval Person." Churchill had chosen the code name when the two began their amiable communication, riffing off the fact that both Churchill and FDR had backgrounds in their respective navies, says the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

In the late 1930s, America was fairly isolationist, and it took Roosevelt repeatedly telling his administration that they would assist Britain and even the Soviet Union if it was attacked by Germany to get Congress on his side. After being reelected, FDR spent the next year laying the groundwork for America's participation in the war. For example, Congress passed a peacetime draft in September. He may not have wanted to tell the people, but Roosevelt felt that World War II would hit American shores sooner rather than later.

Dwight Eisenhower

On May 1, 1960, U-2 pilot Francis Gary Powers was shot down while spying in the Soviet Union, according to Office of the Historian. In 1955, President Dwight Eisenhower suggested a plan allowing the U.S. and the Soviet Union to fly over each other's airspace to keep tabs on their nuclear weapons situation, but USSR leader Nikita Khrushchev refused. Therefore, the U-2 program was developed in order for the U.S. to keep tabs on the Soviet nuclear program without the Soviets being aware.

Eisenhower approved U.S. officials claiming that the U-2 had been on a routine flight and had malfunctioned, when in fact Eisenhower was interested in the program and knew about the Powers flight. The U-2 planes flew at around 70,000-feet high, which was thought to be a height at which they couldn't be detected by ground radar. They were mistaken.

The Soviets took the alive Powers into custody, but Khrushchev stuck to the course of peace. Eisenhower refused to apologize, revealed his knowledge of the flight, and said he intended to continue spying. As a result, the Soviets left the Paris Summit, which had been arranged in order to discuss this very situation between the U.S. and the USSR. Khrushchev gave up on negotiating with Eisenhower, waiting for the election of the next president — John F. Kennedy.

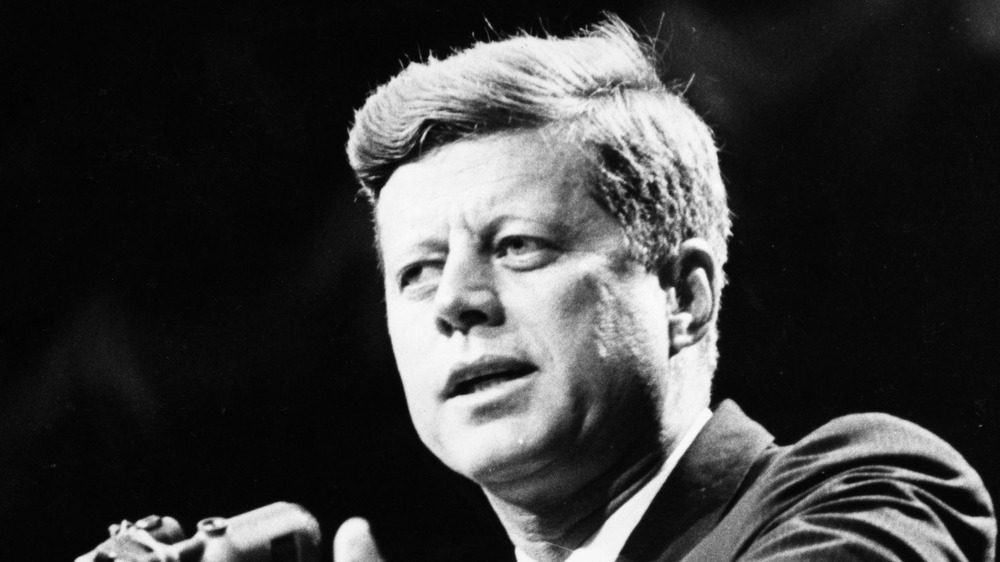

John F. Kennedy

In October 1962, President John F. Kennedy was campaigning in Chicago for the midterm elections on behalf of the Democrats, writes the Smithsonian. The National Security Council's Executive Committee had been informed earlier that week that a Soviet missile base was being built in Cuba. The Committee saw two roads they could go down — invade by way of an air strike or set up a blockade with the threat of something worse down the line.

Since the public needed to be kept in the dark, when the Executive Committee finally decided what to do, Kennedy's staff informed the Chicago press that he would return to Washington, as he was supposedly feverish. The Associated Press ran a story the next day, citing a respiratory infection, though in actuality, Kennedy went for a swim before diving into a five-hour meeting with the Executive Committee. A naval blockade was the route they went with.

Over the next few days, negotiations worked out with the Soviet Union's Nikita Khrushchev for the missiles to be taken away. Though the story about Kennedy's illness did get out, general consensus was that the naval blockade would have been weakened if the public guessed why it was necessary.

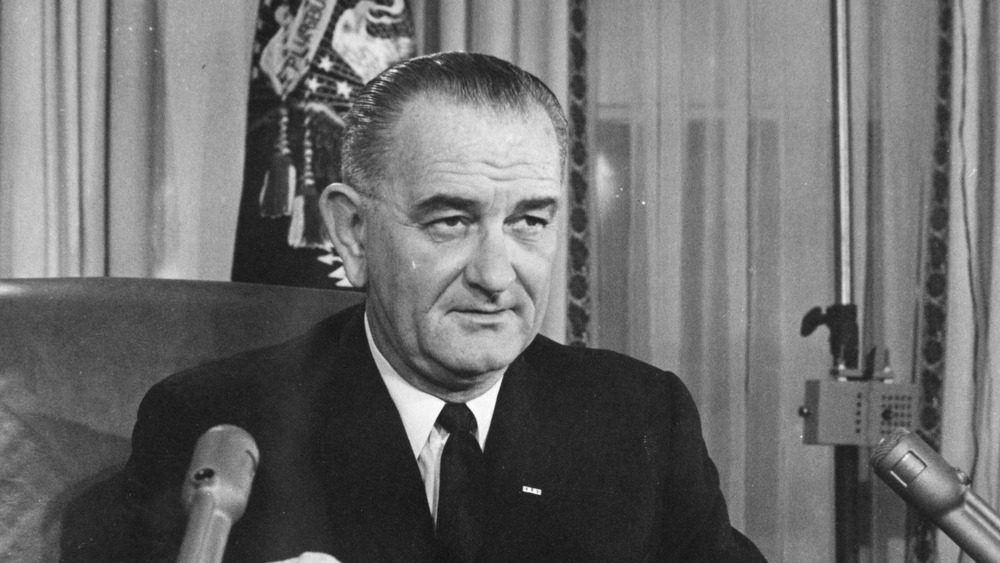

Lyndon B. Johnson

During the beginning of the Vietnam War, the Lyndon B. Johnson administration deemphasized the cost of the war in Vietnam. Johnson figured the war would be easily won, and his administration did not announce he had placed troops in Southeast Asia, according to The Washington Post. His administration also wanted to keep the nation's focus on domestic issues. In hindsight, it's easy to tell that this might not have been the best strategy, since it's difficult to tell just how long a war will really take. Also, shoving one issue into the public eye to distract everyone from something else rarely goes well.

Once on a course, however, Johnson committed to it, appalling Congress six months later when they were forced to allocate money to cover the cost of the war, which had been moved to the Pentagon budget. Though Congress could have battled the money issues by raising taxes, this was impossible simply because Johnson didn't give them the exact cost of the war.

On the domestic front, Johnson was very committed to what he called his Great Society, meaning Medicare, Medicaid, Head Start, and other programs for education and families. As a result, it was difficult to come up with wartime spending. The war also created inflation that threatened many of the programs Johnson wanted to focus on.

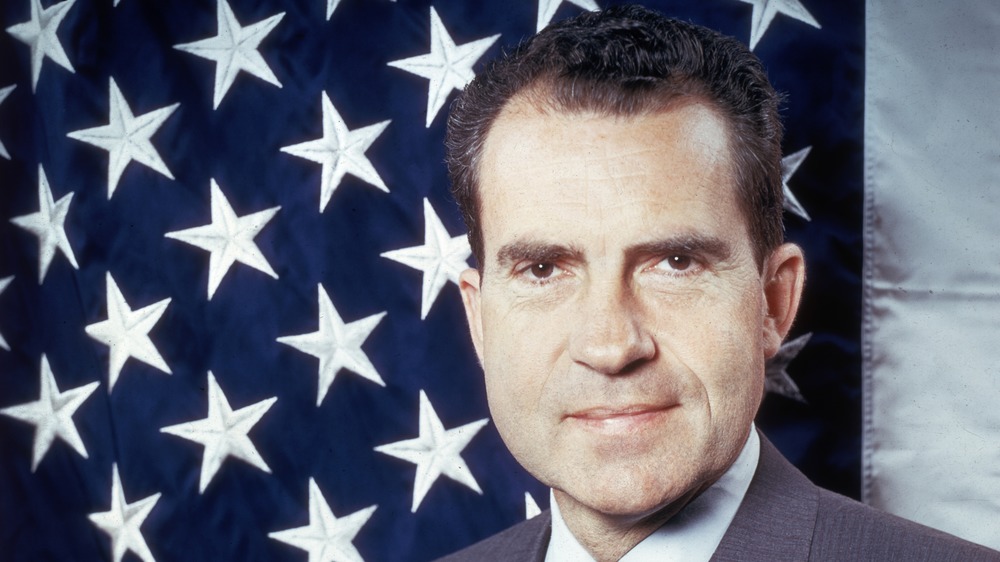

Richard Nixon and the Vietnam War

During the Vietnam War, Cambodia didn't take a side, though the country was used by the Vietnamese to transport supplies and arms. The Ho Chi Minh Trail, which connected Vietnam to Laos and Cambodia, ran throughout the northern part of the country and therefore proved useful to the Vietnamese, according to History.

Bombings of suspected communist camps in Cambodia occurred in early 1969, which President Richard Nixon consented to. The New York Times eventually broke the story of the operation, called Menu, in May of the same year. Though Cambodia wasn't the first neutral country the U.S. bombed (that would be Laos, starting in 1964), international outrage followed. Considering President Lyndon B. Johnson's track record with covering up action in Vietnam, it wasn't the best idea for Nixon to simply follow his lead.

Nixon's unprecedented and unapproved invasion of Cambodia, in late April 1970, ultimately led to the passing of the War Powers Act in 1973, which checked the president's powers to declare war without Congress's agreement. The publication of the Pentagon Papers in 1971 was a further hit to Nixon's war plans, as it revealed the U.S.'s extensive presence in Vietnam.

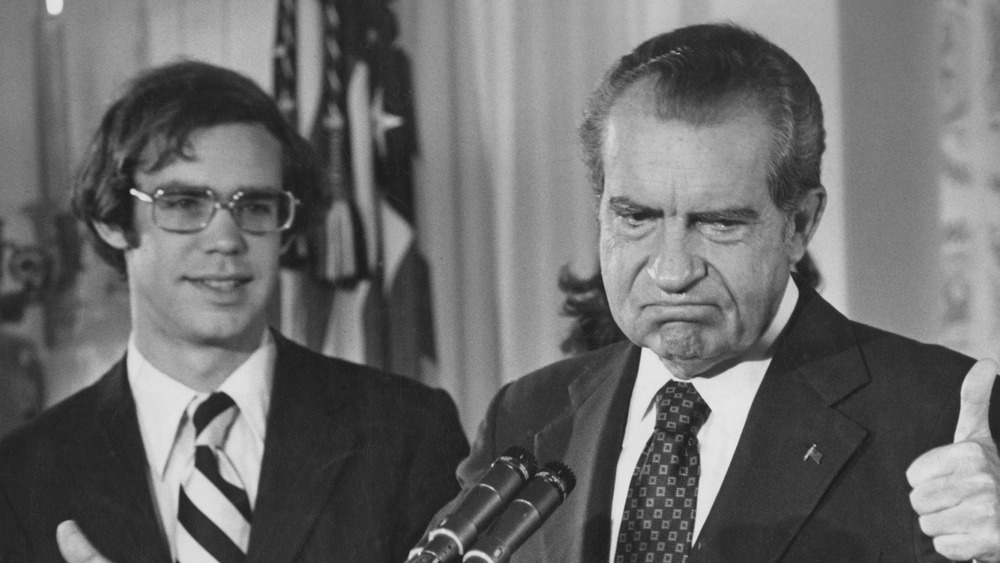

Richard Nixon and Watergate

In April 1973, nearly a year after the break-in to Democratic National Committee headquarters, President Richard Nixon tried to hold the rapidly collapsing situation together by addressing the people to profess his innocence, deflect blame, and incriminate various aides, writes the Miller Center. The Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein had been reporting on the Watergate break-in and cover-up since it had happened in June 1972, according to the Harry Ransom Center, despite initial consensus that it was simply a "caper," with the White House calling it a "third-rate burglary." The U.S. Senate began their own investigation and hearings on May 18, after a series of investigations revealed "a massive campaign of political spying and sabotage conducted on behalf of the Nixon reelection effort" (via The Washington Post).

With the U.S. Senate and The Washington Post collectively breathing down his neck through their investigations, Nixon explained he held his aides (namely, White House counsel John Dean, Chief of Staff Bob Haldeman, and aide John Ehrlichman) responsible. He said that several had resigned.

Too much time had elapsed for Nixon, and his men knew more than they should have. Democrat Sam Ervin chaired the U.S. Senate Watergate Committee, and Nixon's aides began to testify over the next few months. Knowledge of the Watergate tapes (taped conversations between Nixon and his staff) also came out at the Senate hearings. Ultimately, the impeachment process against Nixon began in October 1973 due to the information uncovered in the hearings. Nixon resigned during his second term in office, in August 1974. President Gerald Ford was sworn in a short time after Nixon left the White House via helicopter. Ford later pardoned Nixon (via History).

Jimmy Carter

While campaigning for president in 1976, Jimmy Carter promised the American public that he would never lie to them. That image of forthrightness has endured through the decades. Admirers of the Carter administration look to those years as a time when the White House was free of scandal. Even critics of Carter have accepted his basic honesty. Sometimes, that trait has been cited as a weakness of Carter's; the chief executive of a powerful nation, it's argued, must be prepared to work from the Machiavellian playbook at times.

But Carter's record isn't quite as pure as his words and the collective memory of America would suggest. Like almost every politician, he exaggerated his accomplishments and credentials while on the campaign trail. He inflated Georgia's budget surplus at the end of his time as governor, embellished his knowledge of nuclear physics, and didn't personally read and respond to correspondence he claimed he had. But when Carter published his memoir, "Keeping Faith," in 1982, some critics took more note of his lies of omission.

Editor Robert Kaiser of The Washington Post noted that Carter's book absolved the president of any responsibility for the failings of his administration, while awarding himself all the credit for its successes. It omitted the efforts of staff and skipped embarrassing episodes. Carter was also accused of rewriting the history of Bert Lance, a financial aide whose shady business practices led to Congressional inquiries and Lance's resignation.

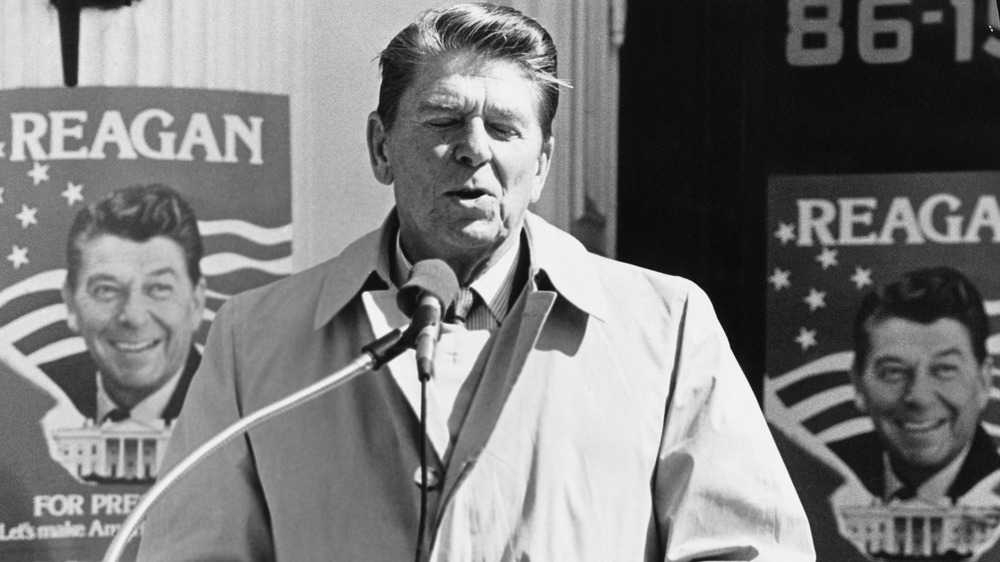

Ronald Reagan

Despite the fact that the U.S. had a trade embargo with Iran in 1986 due to another hostage crisis, in order to release seven American hostages, President Ronald Reagan set up a deal wherein the U.S. sold weapons to Iran in exchange for those hostages, according to History. Three hostages were released, along with $30 million to the U.S, in exchange for 1,500 American missiles. Three other Americans were eventually taken as hostages, however.

Reagan admitted that he had worked with terrorists, after first denying it. The incident would hound the rest of his second term in office. Other than President John F. Kennedy's reportedly necessary lie during the Cuban Missile Crisis, it seems like covering up international deals or invasions never goes well for U.S. presidents.

Attorney General Edwin Meese immediately began an investigation and quickly discovered that $18 million from the $30 million was gone. National Security Council Lt. Col. Oliver North admitted he had funneled it to the Nicaraguan Contras, an anti-communist group fighting the communist Sandinistas, also revealing he believed Reagan was aware of the transaction. After several investigations, three men — National Security Advisor Robert McFarlane, North, and National Security Advisor Adm. John Poindexter, were charged, but Reagan never was.

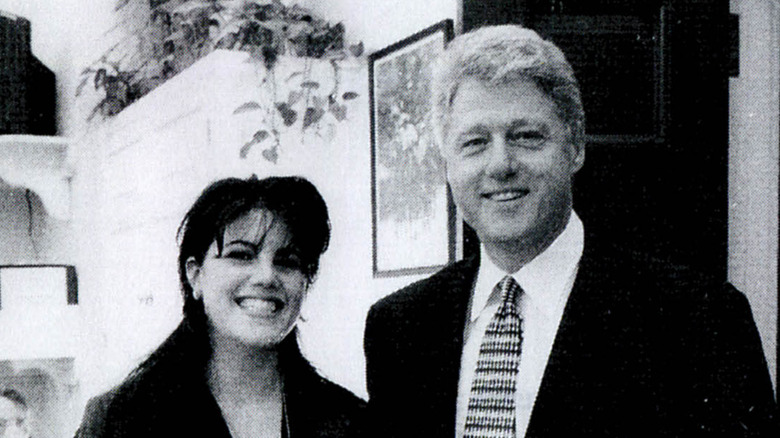

Bill Clinton

In 1995, 21-year-old Monica Lewinsky moved to Washington, D.C. Like most recent college grads, she had an unpaid internship. Unlike most, her internship was in the Clinton White House, for Chief of Staff Leon Panetta. Unfortunately, this internship — and the relationship with President Bill Clinton that came out of it — would change her life forever (via Time).

In January 1998, Clinton denied having a sexual relationship with Lewinsky several times, including on television. Lewinsky denied the allegations as well. However, independent counsel Kenneth Starr received over 20 hours of phone conversations that seemed to say the opposite.

In reality, Lewinsky's and Clinton's relationship had gone on for two years and was eventually uncovered through Starr's grand jury, when Clinton voluntarily testified. Starr's report, released in September of that year, was 445 pages long and contained 11 impeachable offenses. The House of Representatives began an impeachment inquiry, though Clinton was ultimately acquitted in February 1999.

Barack Obama

President Barack Obama's lighthearted statement throughout 2013 that the American public could keep their healthcare plans despite his major legislative changes — aka Obamacare — was proven false when cancellation plans started rolling out, according to PolitiFact. According to the legislation, old plans could be grandfathered in, but if they didn't meet the strict standards, they were canceled. Around 4 million people received notices that their plans were being abruptly canceled. This led to several anecdotes in the news about real people who were being affected by the new law.

What's frustrating is that several people and publications (including the Associated Press, via wbur) noted how impossible this promise would be to keep. Obama's repeated assurances about healthcare didn't fit the complex legislative beast it was actually becoming, so his comments didn't work anymore even though he continued to say them.

Obama's statements were simplistic and didn't even give people an understandable version of the new law, which would have helped. Ultimately, Obama did apologize to the American people for his statements. He also offered a fix by allowing state insurance commissioners to lengthen plans. Even so, his credibility and popularity dropped while all this was in the news.

Donald Trump and COVID-19

President Donald Trump repeatedly lied about and undermined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, including disparaging medical guidance for wearing masks. Trump told journalist Bob Woodward that he always wanted to play down the virus so as to avoid a panic, according to KHN.

Sadly, this only caused other conservatives to further spread misinformation about COVID-19 on social media — for example, several Facebook posts that stated wearing masks does more harm than good (via PolitiFact). COVID-19 had become a global pandemic, and many thousands of people died. On the other hand, this response isn't without precedent, as during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, there were people who disregarded health guidelines. For example, the Anti-Mask League of San Francisco really existed (via History). Yes, really.

Trump also cast doubt on Dr. Anthony Fauci, one of the world's leading experts on infectious diseases. Fauci had advised every president since Ronald Reagan and earned the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his work on the AIDS relief program PEPFAR, according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Trump also overemphasized the supposed benefits of hydroxychloroquine, which caused Poison Control to feel they needed to warn the public about its side effects. For example, COVID-19 patients taking hydroxychloroquine needed to be removed from the drug after developing heart rhythms. Nevertheless, people bought it, leaving patients who needed it for chronic lifelong conditions such as lupus only able to take some of what they needed.

Donald Trump and the 2020 presidential election

During the 2020 election season, and especially after the November 2020 presidential election, President Donald Trump promoted the existence of election fraud, claiming several times that he won the election in a landslide despite the numbers not adding up. His voter base wholeheartedly went along with this, as did several members of Congress, including avid supporter Sen. Josh Hawley (via Huffpost).

Over the following months, Trump sued various states and asked state officials to "find" the votes he needed. In early January, Trump requested Georgia Republican Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to do just that, claiming election fraud, according to Associated Press. He was refused. Trump also seemed to threaten Raffensperger and his lawyer, Ryan Germany, by claiming there would be charges for the illegal destruction of votes in Fulton County, for which no evidence was found.

Ultimately, the endless misinformation led to the attack on the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, by Trump supporters who sought to change the electoral college's decision, where a U.S. Capitol police officer, Brian Sicknick, was killed along with four others (via The New York Times).