The German WWII Superweapon That Launched America's Space Program

It's an exaggeration to say that Nazi technology allowed the United States to pull off the moon landing — but not very much of one. Wars drive innovation, as participating armies strive to figure out how to kill their enemies more efficiently, effectively, or dramatically, and these inventions sometimes find better uses later. So it was with rockets. As part of Germany's plan to extract a blood price for every inch of occupied Europe it lost to the Allied invasion, its scientists invented modern rocket technology and deployed it in the V-2 bomb. While the first exemplars of this new flight mechanism were pointed at London and Paris, after the war, scientists aimed for the stars instead.

In a morally dubious move, the United States also snagged one of the Nazis' best rocket scientists from the ruins of Germany. Wernher von Braun had joined the Nazi party and designed weapons that killed Allied servicemen and civilians alike, but he got one of the best second acts an ethically compromised genius could hope for: an office at NASA and, eventually, U.S. citizenship.

The United Kingdom successfully defended itself against manned German bombers

France's military collapse in June 1940 meant that the United Kingdom stood effectively alone on the Western Front. The Soviet and American juggernauts had not yet entered the war, and every other state in Western Europe was either already occupied or trying to remain neutral. Britain was the nut Germany had to crack to secure its conquests. Two factors saved the United Kingdom: the failure of German imagination and the power of the Royal Air Force. Hitler had assumed that France's defeat would lead Britain to come to terms with Germany, and thus no serious plans for the invasion of Britain were made until weeks after the fall of France.

The plan that Germany did come up with involved pounding British cities into rubble from captured bases on the northern French coast to soften the country up for a planned amphibious invasion. During the Blitz, German attacks hammered London as well as other British cities, famously savaging beautiful Coventry, but the Luftwaffe consistently lost more men and planes than the Royal Air Force — and the United Kingdom was able to retaliate against Berlin and Munich. By mid-September, it was clear that British airspace belonged to the British and that any attempted invasion of the United Kingdom would be blasted out of the water. Bombings continued, but the United Kingdom survived to keep fighting, and Germany made the fatal mistake of turning its unwanted attention to its Soviet neighbor.

By autumn 1944, German control of Europe was clearly in jeopardy

By mid-1944, German control of the European continent was being rolled back along multiple fronts. Most famously, the Allied invasion of Normandy on D-Day had established an effective beachhead in northern France from which troops could open up another front. Paris was liberated on August 25, and on September 4, Antwerp in Belgium was freed of Nazi control. This was especially good news for the Allies, as Antwerp controlled an excellent port facing Britain that could receive men and munitions to further support the drive into Germany.

D-Day was not the only existential threat facing Germany in the summer of 1944. The Soviet counterattacks in the east had hardened into the famous Russian steamroller, with Soviet forces crossing the Romanian border, rolling through Ukraine, and reaching Poland. And Germany's friends were in no position to offer any meaningful assistance, with Italy and Japan facing their own climactic battles. On June 4, two days before the D-Day landing, American forces arrived in Rome, making the Eternal City the first Axis capital to fall to Allied forces. Japan was faltering in the Pacific, abandoning outposts and losing battles in the Mariana Islands. It was all over but the shouting — but Germany was planning a couple of final war cries.

Germany had been developing the technology for the V-1 and V-2 since 1936

In November 1939, a German physicist named Hans Mayer took a big risk. Dismayed by his country's invasion of Poland and the future it indicated, he anonymously contacted a British naval officer in Oslo, Norway, to arrange a transfer of information: If a coded phrase was incorporated into a certain BBC broadcast, the officer, Hector Boyes, would receive documents outlining some planned German weapons. Boyes arranged for the code to be transmitted, received the materials, and had them translated and sent to London.

It was almost too much. The wide range of information in the documents, covering targeting systems, torpedo design, and the long-range rocket concepts that would birth the V-1 and V-2, as well as the anonymous source, led some in the British intelligence establishment to consider the "Oslo Report" to be a likely German plant intended to deceive or confuse the British. But as the war continued, British forces found themselves facing weapons very, very similar to those described in the Oslo Report, and the information the dossier contained helped design countermeasures.

Mayer was sent to a concentration camp in 1943 but survived. He died in 1980, having privately confirmed his identity to one of the British researchers who used the Oslo Report after the war, and his name and role in undermining the German war machine remained secret until 1989.

The V-1 and V-2 were developed by whiz kid Wernher von Braun

Under the terms of the World War I-ending Treaty of Versailles, which limited Germany's armed forces in hopes of preventing another continent-smashing war (oops), Germany could not possess or develop long-range artillery. While the Nazi state would of course shred the treaty, this stipulation did inspire a new line of thinking in German weapons development: Rockets were not explicitly forbidden!

The German scientist most critical for weaponizing this loophole and developing the rockets that would bombard Paris and Antwerp was Wernher von Braun. Born an aristocrat (you can tell by the "von") in a part of Germany that's now Poland, von Braun was an indifferent student in his youth but fascinated by space. This fascination led him to finally apply himself to his studies, and he worked until he excelled. In 1930, while still a student, he joined the German Society for Space Travel.

By 1934, private and academic rocket research was forbidden — but not military research, so von Braun found himself directing a military research center in his mid-20s. At best, von Braun went along to get along, joining the Nazi party in 1937, signing up for the SS paramilitary squad in 1940, and being elevated to the rank of major in the SS in 1943. While surviving records don't indicate any particular enthusiasm for the Nazi project on von Braun's part, he was certainly willing to cooperate with genocidal expansionist warmongers so he could keep playing with rockets.

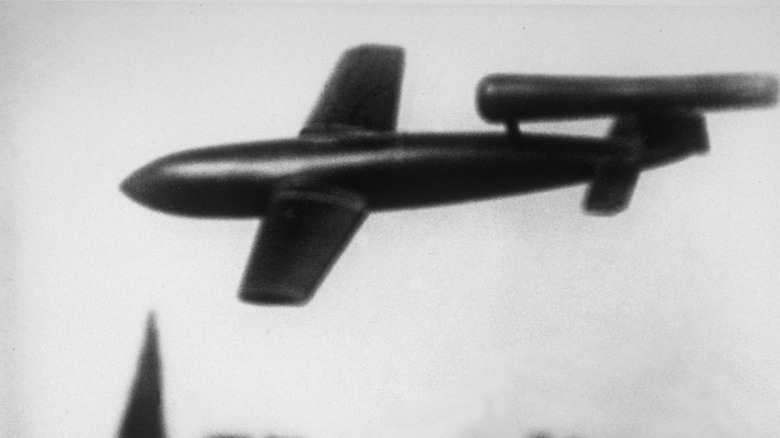

The V-1 was an unmanned bomb on wings

Two of the weapons Wernher von Braun and his team worked on at the Peenemünde rocket development center on Germany's Baltic coast came to be designated "revenge weapons." With German control over the continent crumbling, Hitler and his government wanted to keep the Allied military and civilian death tolls high, hoping they could still blunt the multi-pronged advance into the Nazi heartland. The German term for "revenge weapon" is "Vergeltungswaffen," and so these weapons became known as the V-1 and the V-2 so people could avoid saying "Vergeltungswaffen."

The V-1 was the first to be deployed and, though frightening, was not an enormously effective weapon. The basic idea of the V-1 was a small airplane, complete with wings and jet engines, but instead of carrying people or cargo, the body of the craft was packed with explosives. Because they were unmanned, V-1s were difficult to aim and followed low, straight glide paths after they were launched from ramps or retrofitted bombers. These right-across-the-plate flight patterns meant they were relatively easy for anti-aircraft guns to take out, with thousands neutralized: More than 8,000 were launched at London, but only about 2,400 struck the target area.

While 2,400 bombs is a lot to hit a city, the "doodlebugs" turned out to be a much less fearsome weapon than Nazi war planners had hoped. Their kid brother, the V-2, would be far more destructive.

The V-2 was more innovative

The V-2 was first test-launched in October 1942 but first used offensively in 1944, when they were fired at liberated Paris on September 6. The V-2 was enormous, as tall as a four-story building, and weighed over 28,000 pounds, burning as a propellant a mixture of alcohol, water, and liquid oxygen. The 1,600 pounds of explosives each V-2 carried could reach over 200 horizontal miles; from London to Calais on the French coast is a little under 100 miles, so V-2 launch sites in France could easily reach much of southern England, and sites in Belgium and the Netherlands could still reach London. The V-2's arcing trajectory and supersonic descent meant it was far harder to intercept than the comparatively slow and trackable V-1.

The usual height a V-2 could expect to reach was about 50 miles, but a test missile fired in June 1944 reached 109 miles of altitude. This was the first manmade projectile to reach the edge of space, a grim feat considering the circumstances but an important milestone for those hoping to explore beyond the Earth.

V-2s were launched against France, Belgium, and the United Kingdom

They might not have been the war-winning wonder weapon the Germans had hoped for, but the V-2 rockets were much more effective than the V-1s. Not only were they more likely to breach enemy defenses, but they were also very frightening, as their faster-than-sound descent meant that you only heard them coming toward you after impact — if you survived. Germany fired V-2s at London and Paris to try to sap the enemy's will to fight, as well as at Antwerp in an attempt to frustrate Allied efforts to use its port for resupplying missions. The bombs caused enormous civilian casualties, with about 30,000 killed and injured in England alone and hundreds of thousands made homeless.

Too fast to track and too unpredictable to plan for, the V-2s could only really be taken off the board by having their launch sites destroyed or captured, which the Allies eventually did. The autumn and winter of 1944 was a scary time to be in the Nazi crosshairs, but the people of bombarded London and recently occupied France and the Low Countries had lived through worse earlier in the war. Allied morale was not broken by this 11th-hour weapon. On March 27, 1945, the last V-2 hit London, and a few weeks later, Germany lay broken and dismembered before the victorious Allies.

V-2s were made with slave labor at the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp

True to Nazi form, the V-2 rockets were constructed with slave labor. Allied air attacks were walloping German arms production, so weapons had to be built underground to keep them out of reach of enemy attacks. These underground production facilities were, of course, also made with slave labor. The V-2 was built at a concentration camp and arms depot called Dora-Mittelbau, which had been spun off from the even more notorious Buchenwald in 1944. Deep in central Germany and with factories hidden under the Harz Mountains, Dora-Mittelbau was as safe as anywhere from Allied attacks.

Conditions at the camp were horrific. Prisoners stayed underground most of the time, where they had no access to light and fresh air, and were transferred to other camps to be murdered if they became unable to continue working. More than 200 captives were publicly hanged for alleged sabotage, and the general death toll here was higher than at many other forced labor camps throughout the Nazi sphere. All told, 10,000 enslaved workers probably died in the V-2's construction — more than were killed by the rockets when they detonated.

And for the record: Wernher von Braun knew about all this. He claimed after the war not to have been involved in sabotage reports that led to executions (unknowable) and not to have participated in the decision to build the camp (possibly true), but he is known to have requested the transfer of prisoners with relevant skills to the facility at Dora-Mittelbau.

V-2 rockets had serious limitations

As high as German hopes were, the V-2 did not really change the progress of the war. Psychologically, it's difficult to imagine any of the Allied participants giving up in 1944, after five bloody years of the war in Europe. And tactically, while the V-2 was damaging and frightening, it simply wasn't powerful or plentiful enough for Germany to pull out a last-minute win.

The V-2 was very expensive and labor-intensive to build, and even with an enslaved labor force, it simply was not a very good use of Germany's dwindling resources. They were also not very accurate: You could point them at, say, "London" and be fairly confident of a hit, but you couldn't aim at "Buckingham Palace" with any confidence of success. The targeted strikes on military and industrial sites that might have significantly helped Germany were not yet possible, and the Nazis were running short on, along with everything else, research and development time.

Perhaps most to the point, the V-2's capacity to damage Allied-held cities was far less than the Allies' ability to absolutely pulverize German cities. About 5,000 people in total were killed in V-2 attacks. During the bombing of Dresden, 24,000 people were killed in a mere two days. The comparative rate of destruction was very much in the Allies' favor, and there would never be enough V-2s to change that now.

After the war, all the Allies wanted a piece of the program

In the waning days of the war in Europe and after its end, all the Allies were interested in profiting from the German rocket program — after all, the best enemy weapon is the one you can confiscate and point at someone else. With the war in Japan not quite over and postwar tensions between the Soviet Union and the West appearing inevitable, German rocketry was a potential boost everyone wanted to make use of.

Captured weapons and facilities gave Allied researchers plenty to start working on, but the real prize was the scientists who had developed it. Both the United States and the Soviet Union made deals with Nazi scientists, offering them the do-over of all do-overs. The Soviets even kidnapped a handful of scientists who were reluctant to take their deals, and in this situation it's hard to feel all that sorry for the newly Soviet researchers.

The United States snagged the biggest fish, though. Wernher von Braun was one of the scientists gobbled up under Operation Paperclip, an American plan to turn 1,500 useful German and Austrian scientists and technicians, along with their families, into Americans. For people with valuable scientific or industrial knowledge, a Nazi past could be hidden under a fresh coat of paint, swapping strudel and genocide for apple pie and baseball.

Von Braun lands at NASA; the U.S. lands on the moon

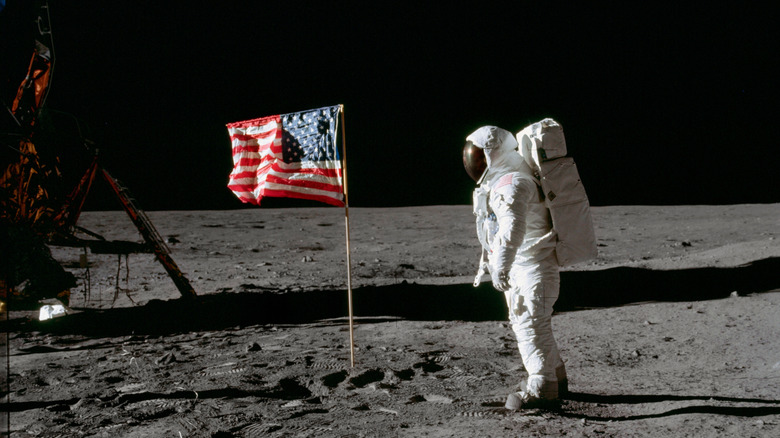

Wernher Von Braun spent his first few years in the United States on military research, though his interest in space continued — he even narrated some Disney-produced television programs on outer space. In 1960, von Braun's rocket development unit was transferred to the newly minted NASA with instructions to produce large rockets. The result was the Saturn V, the vehicle used in all the Apollo space launches. One of these, Apollo 11, brought the first human beings to the surface of the moon in 1969.

Von Braun had, indirectly, made it to the moon. He had to answer some uncomfortable questions for a West German court in 1969, but for most of his postwar life, von Braun avoided heavy public criticism for his wartime role. (Satirist Tom Lehrer did skewer him in a song that included the lyric "'Once the rockets are up, who cares where they come down? That's not my department!' says Wernher von Braun.") Serious questions about the Nazi links of some immigrant scientists of the Paperclip cohort arose in the 1980s and 1990s, but von Braun had made another well-timed escape: He died in 1977.