These WWII Weapons Were Total Disasters

Given the sheer scope of World War II, it naturally follows that a lot of weapons got involved. Getting a handle on the exact numbers is difficult, given the number of nations, manufacturers, and soldiers involved. But it's estimated that 27 million rifles and carbines alone were produced from 1939 to 1945, with the U.S. and Soviet Union each manufacturing over 12 million per nation in that period. And then consider all the extra firepower that can be added to that number when you factor in tanks, explosives, aircraft, seafaring vessels, and more. Like so much about the Second World War, trying to understand the full scope of things can get dizzying.

What makes things even more incomprehensible are some of the failed weapons of the war. While some manufacturers were reliably churning out rifles, others were developing, testing, and even sometimes deploying far stranger weapons. Things could get especially weird in the more desperate times of war, whether that was when Nazis threatened Britain from just across the English Channel or Germany itself was feeling the increasing pressure of Allied advances into Europe (so much for Hitler's plans for the U.S. on the increasingly distant chance he won the war). The Pacific theatre saw some odd tests and attempts, too, while even seemingly far away ground in the U.S. was witness to one overly successful and decidedly strange weapons test. These are the ones that proved to be serious disasters.

The Krummlauf only sort of worked

The idea of a bent-barrel gun sounds so cartoonish that it might as well have been wielded by Elmer Fudd, but sometimes the details of WWII are truly bizarre. Case in point: the Krummlauf. No, the images aren't doctored — that really is a bent-barrel gun meant to shoot around corners. As the war progressed, Nazi Germany was up for seemingly anything in the weapons development department that would give them some sort of edge against the Allies. Frankly, the Krummlauf was one of the less ridiculous ideas bandied about, at least when compared to quasi-mythical things like the orbital "sun gun" (never mind that human spaceflight hadn't been figured out just yet). It was a relatively simple attachment that went onto a German soldier's rifle and came in two versions: One with a 30-degree angle and another that tried to wing a bullet around 90 degrees.

Mirrors helped soldiers actually aim the thing, but when it came to the whole hitting-a-target business, the Krummlauf was a dud. The angled barrel did a number on bullets and often broke them into bits or at least dramatically reduced accuracy. What's more, the pressure of gasses inside the barrel put serious stress on the bend. Designers attempted to address this by placing vent holes in the first part of the barrel, but even so, the Krummlauf only lasted a few hundred rounds before it bit the dust.

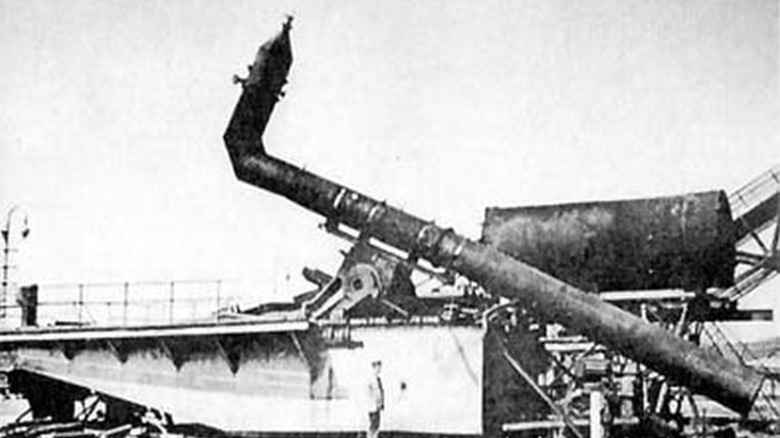

A railway gun was more boom than substance

In the depths of war, it may be tempting for forces to develop weapons that are meant as much to instill fear as any actual damage. That must have been at least part of the motivation behind the Schwerer Gustav railway gun, which was used by Germany in 1942. Actually, its development goes a bit further back, as Hitler was inquiring about making a really, really ridiculously big gun by the mid-1930s. His plan was to break through the Maginot Line intended to protect France, though the gun wasn't put together in time.

Still, the Krupp armament company went ahead and produced what was, essentially, a standard gun scaled up to ridiculous proportions. So large, in fact, that Krupp had to custom-manufacture not just the gun's parts but also the equipment and facilities needed to make it happen. Naturally, it took forever to make the thing, with Krupp only producing a working model that was test-fired in August and September 1941. The gun, also known as the "Gustav-Gerät," didn't actually go into action until the next year, when it was assigned to a unit that gave it the incongruously cute nickname of "Dora."

The gun came in at about 1,350 metric tons and was capable of firing a 7-ton shell 29 miles. It must have been terrifying for the people of Sevastopol, the Soviet city bombarded by the Schwerer Gustav ... until the 106-foot-long barrel wore out. A second version of the gun never even made it to the front.

The Maus tank was too big to succeed

Taken completely out of context, a tank named Maus sounds almost cute. But when you learn this vehicle of war was built for the Nazis and Wehrmacht to use, things get considerably less warm and fuzzy. Oh, and then the thing was huge, meant to be a nigh-indestructible machine that would bring death and destruction wherever it went. Thankfully for everyone else, the Maus was a mess.

Designed by automotive engineer Ferdinand Porsche (who also designed the Volkswagen car), the Panzerkampfwagen "Maus" was one of quite a few war vehicles thought up by Porsche and his son, Ferdinand Jr. But while some of them, like the oversized Tiger tank, earned a reputation in combat, the Maus was a different story. It was huge and armored, yes, but the prototypes were plagued by mechanical issues and only ever reached the screaming speed of 12 miles per hour.

Perhaps the 188-ton weight of the beast had something to do with it. Then, there's also the matter of the timeline, as the Maus went into production relatively late in the war in 1943. Allied bombing campaigns destroyed the facilities where its drawings and life-size wooden model were kept, further hampering the program. Though two prototype versions were completed, they only came into existence in late 1944. By 1945, Soviet forces had blown them up and taken the debris for examination, bringing the long, fruitless tale of the Maus to its conclusion.

The bat bomb backfired on its testers

A bomb delivered by bat sounds too ridiculous, but the U.S. Army was interested enough that it very nearly became a real, if weird, WWII mission. But, unlike some other disastrous weapons of the Second World War, this one was a bit too successful. It was the brainchild of Lytle S. Adams, a dental surgeon who also happened to know first lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Perhaps that's why his 1942 letter to the White House passed through, even though it described his idea of strapping incendiary bombs to bats and dropping them over an enemy city.

The notion, inspired by a trip to Carlsbad Caverns, was that the bats would naturally roost around buildings and start massive fires when their bombs detonated. Adams was not a fan of the creatures, writing in his missive that bats were the "lowest form of animal life" and that God had created the icky things "to await this hour to play their part in the scheme of free human existence" (via Air Force Test Center). Roosevelt concluded that the idea sounded odd but held potential. And so, 1943 saw Army soldiers collecting bats from Carlsbad Caverns and strapping incendiary bombs to the animals.

When they were dropped from a plane, the bats really did roost in nearby structures. Only, those were the buildings of the Carlsbad air base, including barracks, offices, and airplane hangars. These, along with the base's control tower, were soon aflame. Despite this striking proof-of-concept test, the project was abandoned when the military concluded bats couldn't take direction as well as human operators.

A trench digger had little place in WWII

Trenches are one of the most enduring symbols of the First World War. But, by the time WWII came around, war had changed. Technology like more advanced aerial bombardment meant that soldiers hunkering down in trenches was somewhat less common. So, why did Winston Churchill get so involved with a dud of a trench-digger weapon?

Part of it may have had to do with optics, as Churchill took office as prime minister in May 1940, when things in Britain were feeling pretty gloomy. The trench digger — given the codename of "White Rabbit No. 6," then "NLE Tractor," and eventually "Nellie" — was more akin to a humongous tank that would have slowly but powerfully cut a trench for soldiers following behind. The British government was at first on board and approved production of both narrow- and wide-format models.

But then Nellie ran into trouble. Originally, the digger was meant to be run by airplane engines, but that plan was scrapped in favor of diesel models to free up engines for fighter planes. Then, the fronts where it would have operated began shifting, further complicating matters after Britain had already done soil testing in France and Belgium. Then, there was the pervasive problem of manufacturing delays, supply line issues, and the fact that aerial assaults could skip over front lines anyway. Ultimately, out of the 200 or so machines commissioned, only 10 were made, and none appear to have been used in combat.

Kaiten were terrifying and often ineffective

Even today, the notion of kamikaze aircraft can be pretty terrifying. Sure, they were something of a last-ditch attempt to gain an advantage in the war by an increasingly stressed and hard-struck Japanese military. But the psychological impact of seeing an explosive-laden plane intentionally piloted into Allied craft was striking, to say the least. What may be less known is Japan's kamikaze efforts were not confined solely to aircraft squadrons. They also included kamikaze divers known as fukuryu, explosive-laden boats called shinyo, and, perhaps most chilling of all, human-powered torpedoes known as kaiten. The motivation to add doomed sailors inside the torpedoes was to improve their guidance with human pilots. After testing claimed the lives of at least 15 kaiten test pilots, the torpedoes were first deployed in battle in late 1944.

Yet, for all the shock and awe involved, the overall kamikaze effort wasn't all that successful. Planes could be difficult to control, especially at high speeds, and reportedly often crashed into the ocean rather than the vessels they were targeting. Allies had also keyed into the kamikaze effort and used their own guns, radar technology, and aircraft to launch specific counteroffensives. Meanwhile, kaiten appear to have done more damage to Japanese sailors than enemy ships. They have been credited with sinking the USS Mississinewa and USS Underhill, but little else. And while 187 Allied personnel were killed by kaiten crews, it's estimated that many more on the Japanese side died in the kaiten program, either transporting the torpedoes or in the torpedoes themselves.

The Panjandrum would have been hilarious if it weren't so terrifying

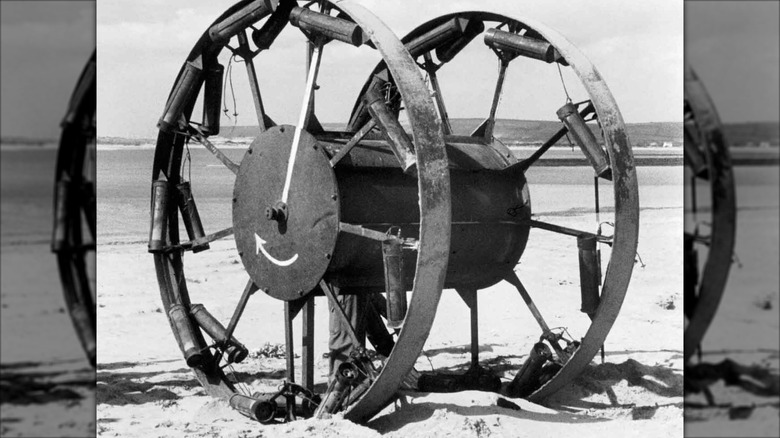

What if, instead of sending soldiers into a battlefield to struggle over obstacles and launch or plant a dangerous explosive against the enemy, you just ... sort of send the bombs on their own? That's the general idea behind the Pajandrum, a gigantic wheel powered by rocket technology that British developers hoped would deliver a bomb to German forces hiding behind a defensive line. That almost sounds reasonable, except rocket technology was very definitely in its infancy during the 1940s.

Engineer Nevil Shute Norway designed the weapon to help Allied forces breach the concrete sea walls Germany was building along the Atlantic coast. It would carry a 1-ton bomb meant to blast through a wall, incapacitate nearby forces, and allow Allies to come in and seize key ports. The Panjandrum, as Norway's team would call it, looked like a massive drum with wheels. Those wheels were spotted with carefully spaced rockets to provide propulsion, while the center axle contained the explosive charge.

The device made it as far as the test phase, which was unusually carried out in public (needing to run it on a beach made secrecy all but impossible). Yet the rockets kept popping off and pushing the Panajandrum off its course, so alarmingly that observers — including military officials — dove for cover. Ultimately, the lack of any real piloting system or ability to course-correct doomed the ridiculous spectacle of the Panjandrum.

The Windkanone had an embarrassing single deployment

Today, a wind cannon is more likely thought of as a silly children's toy and not a weapon of war, but things were pretty different in WWII Germany. As the Allies were increasingly successful, Germany was faced with shortages that hampered its ability to fight in conventional ways. If munitions factories have been bombed and supply line disruptions mean no one can get the parts to repair tanks and aircraft, what is one to do? Get weird ... or desperate. Enter the rise of Wunderwaffen, or "wonder weapons," that were meant to skirt these problems and scare the pants off the enemy. Some Wunderwaffen still loom large in the imagination, like the (only quasi-successful) supersonic V-2 rockets, while many other Wunderwaffen proved to be expensive, time-wasting failures. The Nazi wind cannon very definitely falls into the latter category.

Called simply the Windkanone, the weapon shot a blast of heated nitrogen and oxygen, lobbing a vortex of these gases at a target. Oh, and it was huge — the barrel was about 32 feet long — and therefore expensive and time-consuming to build. Still, its inventor, Austrian scientist Mario Zippermayr, had been able to build other vortex cannons and clearly thought this one was ready for a bigger test than breaking wooden boards at a distance. But when it was set up on a bridge over the Elbe River, it proved a dud that was incapable of reaching the heights of Allied planes.

The Maginot line offered practically no defense at all

The Maginot Line makes sense in theory. It was built in the 1930s by French forces attempting to keep the land-hungry Nazis out and consisted of a bristling array of munitions, steel-reinforced concrete, minefields, and more that stretched over 280 miles. It was immensely expensive (adjusted for inflation, it would be billions today) and was widely considered to be one of the most up-to-date fortifications of its time. Then, the Nazis basically strolled around it and into France.

What made the Maginot Line perhaps one of the worst ideas in history? For one, the designers didn't always account for advances in technology and tactics. Though perhaps that's not entirely fair, given the technological advances that were present in some parts of the Maginot Line, with some locations including underground fortresses with hospitals, train lines, and barracks. But the line essentially stopped at wooded areas of Belgium they considered to be impassable, namely the Ardennes Forest. Ultimately, Nazi tanks and over 1 million soldiers supported by German aircraft traversed it in short order.

Meanwhile, resource-strapped French forces couldn't do much to combat the invading force. This meant that one of the proposed uses of the Maginot Line — stalling the Germans long enough for France to get an army moving — was quickly pointless. Though the fortifications saw some wartime action and Cold War-era usage, many of these structures have fallen into disrepair or been repurposed.

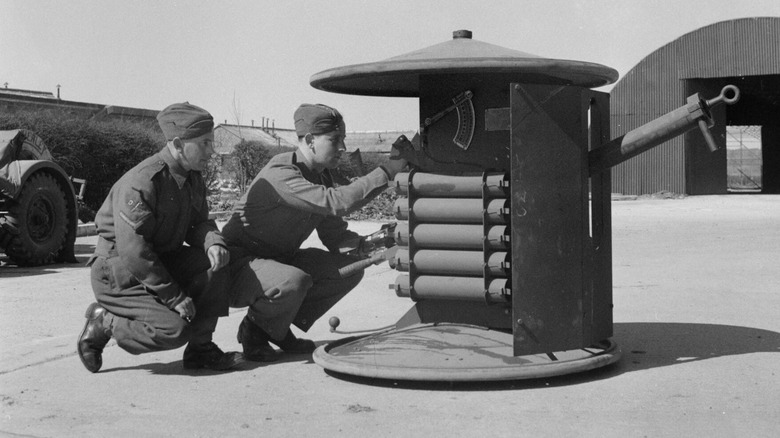

Using the Smith gun was a clunky process

On paper, the Smith gun sounded almost reasonable. Meant for the British Home Guard, it was developed in response to the Dunkirk evacuation of 1940, which left weapons and other supplies abandoned on mainland European beaches. William Smith, the chief engineer of manufacturing company Trianco Limited (which also produced toys), came up with the idea while trying to brainstorm short-order weapon designs to fill the post-Dunkirk gap and lent his name to the result that actually made it off the design table.

The Smith gun was essentially a large tube with two wheels on either side that could be handily pulled behind a civilian vehicle. When called into action, it was meant to be tipped onto one of those wheels, while the center section would unveil a gun. The operator would get some shielding from the wheel above them, though the weapon itself wasn't especially powerful, with a 500-yard range that went down to a mere 200 yards when firing anti-tank rounds.

That is, if the rounds found their target. The Smith gun was notoriously inaccurate, and because some of the shells that came with it had poorly made fuses, Home Guard commanders worried it would be more dangerous to British defenders than anyone else. Admittedly, the Smith Gun was intended as something that could be designed and put into service quickly as Nazi forces loomed. And while some dismissed the Smith Gun, about 10,500 were made, and some Home Guard personnel appear to have grown fond of the clunky thing.