Inside The Biggest FBI Sting In History

While the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is more or less a public-facing operation, the high-level law enforcement agency gets up to a lot of secretive stuff. It has to work in a low-key, hush-hush manner if it's going to do what it needs to do, which is to catch the worst, most prolific, and dangerous offenders who conduct their business across state lines and even internationally. Sometimes, its methods can be questionable in retrospect. Music has triggered FBI investigations, and the bureau has maintained files on plenty of celebrities, but it's also sought out and caught criminals on its famous "Most Wanted" list. Basically, the FBI is a very complicated agency with a complicated way of thwarting, catching, and stopping illegal activities, like murder, trafficking, and drug distribution.

With access to all kinds of technological tools, the FBI can keep tabs on virtually anyone that it believes it needs to watch, such as international criminal syndicates. From the late 2010s until the early 2020s, the FBI was the instigator and lead office on a massive global mission it called "Operation Trojan Shield." One day in June 2021, it all came to a head, with hundreds of suspected law disobeyers of the highest and most egregious order all arrested virtually at once. Here's the behind-the-scenes story of the biggest FBI sting in history.

First, the FBI took down an encrypted phone service

In 2018, the San Diego branch office of the Federal Bureau of Investigation helped shut down Phantom Secure. The company distributed encrypted communication tools, like phones, to known criminal organizations. These affiliated parties used the devices to freely exchange secure and private messages related to the national and international trafficking of illegal materials. The U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of California prosecuted Phantom Secure CEO Vincent Ramos and other executives on charges of facilitating the transnational importation and distribution of narcotics. But then it realized that as soon as one secure communications network went down, another would certainly rise to fill the void. Surveillance indicated that criminal entities jumped from the shuttered Phantom Secure to similar services, Sky Global and EncroChat.

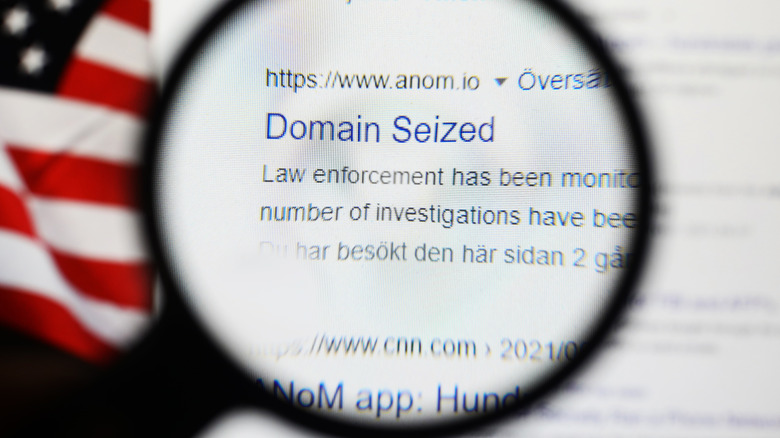

Just before Phantom Secure went defunct, a higher-up with the company known only as Afgoo had just created another similar phone service. Knowing that they would likely face steep punishment for their involvement in the old company, Afgoo went to the FBI with a deal: For less prison time, they'd hand over his sophisticated encrypted communications system, ANOM. As that individual also had a way of accessing the subscriber base of what was once Phantom Secure, they allowed the FBI to take over development — and eventually, the operation — of that nascent service.

The bureau distributed bugged phones around the world

After Afgoo created a backdoor into the encryption software, the FBI and the Australian Federal Police tested it out. He gave ANOM-enabled phones to underworld figures in Australia, and they used the devices to arrange crimes. The FBI saw everything, while the Australians were so pleased with ANOM that they spread the word across their vast criminal networks. They referred interested parties to Afgoo, who placed large orders of phones that had been stripped of all features and functions except the encrypted communications software.

By setting up an international trade for phones that were used to help people commit high crimes, the FBI ironically avoided being accused of entrapment by those that it caught. Afgoo helped individuals and organizations get their hands on phones through gossip, the underworld grapevine, and person-to-person viral marketing. This means the FBI didn't actively push or force anyone to buy the phones and software it used for espionage and surveillance purposes.

The FBI and Afgoo initially outsourced the installation of ANOM to a low-key electronics firm located in Hong Kong. But after the service experienced a rise in popularity after the end of EncroChat, it hired a Dutch technology expert known only as Wijzijn, who set up an ad hoc network of small computer towers and cables that could make 15 ANOM phones per minute. Over 18 months, over 12,000 ANOM devices were sent around the world, used by 300 criminal syndicates in more than 100 countries.

A drug kingpin tried to take over the app

After Phantom Secure got busted and EncroChat was infiltrated by the French government, in came Sky. It charged as much as $2,000 for six months of service, but ANOM asked for as little as $600 for half a year of unlimited message exchange. That pricing scheme is part of what made ANOM so attractive to criminal organizations and their leaders. Particularly Sweden-based crime boss Maximilian Rivkin, who went by the code name of Microsoft, which reflected his vociferous use of technology to run his empire.

In 2020, Rivkin traveled to Istanbul, Turkey, to meet with Hakan Ayik, head of a dangerous cartel that trafficked many of the most deadly drugs into Australia. An early adopter of ANOM, he was looking to expand the operation into Europe, and he recruited Rivkin because he was so well-connected. Together, they spread the word about ANOM while trashing Sky, warning others that it was likely to get compromised because it was based in Canada (one of the "Five Eyes" countries that share law enforcement information with one another). Ironically, Rivkin advocated for ANOM. In fact, he was so taken with both its supposed privacy measures and fortune-making potential that he conspired to take over the entire company, stealing the ANOM phone-making machinery from FBI-affiliated Dutch operative Wijzijn. All of that was, of course, watched and logged by the the bureau.

ANOM stopped a lot of serious crimes before they could happen

By the time ANOM was up and running on phones distributed throughout criminal networks (on what was basically a word-of-mouth referral basis), the messaging service was transmitting countless details of crimes in action back to the FBI. By 2020, the American agency was overwhelmed with texts and the raw, blunt, and clearly stated data and details about illegal things that had happened or were about to happen. So much so that it had no choice but to start outsourcing.

The FBI could tell where the phones loaded with ANOM were located, so it knew exactly where to tip off regional and local law enforcement. The messaging service had become the communications app of choice for criminals throughout Europe, where organizations believed it to be so thoroughly encrypted as to be totally private. As bad actors exchanged information about drug shipments and other activities, the FBI allowed European law enforcement access to the existing ANOM files as they came in.

Agencies didn't wait until the sting was over to take down certain enterprises, however. The criminals were blindsided as cops would break up crime rings and illegal operations seemingly out of nowhere. In Sweden alone, the FBI says that 12 murders were prevented while authorities used ANOM data to shut down various criminal enterprises, including a methamphetamine production ring known as the Firm.

Why the biggest sting in history went down when it did

By the sheer volume of people involved and arrests made, June 8, 2021 may go down as the biggest single-day bust of all time. Every single person arrested had unwittingly exposed illegal actions by telegraphing and self-reporting via their use of ANOM. But why did Operation Trojan Shield, as it was known, have to come to an end in June 2021? Time was running out, both in terms of on-the-level legal arrangements and because the project had been compromised — it was beginning to raise suspicions among the very people it was tracking.

ANOM was such a popular app that it required multiple large servers in various parts of the world to function correctly, so the FBI had to contract with other countries to strategically locate those devices. In some places, that requires a warrant or legal permission from local governments, and those are only valid for a certain period of time. One of the warrants expired on June 7, 2021, making any data collected from the server it covered inadmissible and invalid after that point. This drove the Operation Trojan Shield reckoning on June 8, 2021.

Inklings that ANOM wasn't really secure started to surface before the sting

That logical, legal, and natural expiration date of Operation Trojan Shield also happened to arrive a few months after the true nature of ANOM was first publicly questioned. In March 2021, an individual purporting to be an online privacy and security advocate with the handle of "canyouguess67" exposed ANOM on a blog called ANOM Exposed. "In my findings and questioning of many individuals out there I ascertained aside from ANOM being a total SCAM and a complete setup that not everyone who uses a secure handset is actually a so called 'Criminal,' many are simply just privacy conscious individuals with no understanding of technology," they wrote.

The most telling piece of evidence that suggested ANOM was a data-gathering government op: The locations of the computers used. The blogger pointed out that a high number of IP addresses related to the site corresponded with that of government offices known to readily share information with one another. Namely the U.S., U.K., Australia, Canada, and New Zealand — the "Five Eyes" countries, as we mentioned earlier.

The FBI pulled off the most massive criminal takedown ever

Operation Trojan Shield intended to help disarm the world's biggest threats that few people know about and combat large-scale drug production and trafficking and money laundering. In the end, though, it became the most successful law enforcement sting in terms of sheer numbers. Over about one day in June 2021, more than 500 individuals were arrested for crimes talked about on ANOM. The arrests began in Australia and wound through Europe and beyond after a federal grand jury indictment was unsealed in San Diego, site of the FBI branch office that spearheaded the scheme.

If we include the arrests made for ANOM-revealed acts of criminality before the final sting and closure of Operation Trojan Shield, more than 800 people were detained by local police agencies around the world. Watching and collecting info from ANOM was crucial, as 27 million messages were captured. Around 12,000 enabled phones had been distributed over the length of the project, and 9,000 were still in use at the time of the sting. Through its phone company, the FBI managed to reach and spy on more than 300 criminal groups, including gangs, drug smugglers, and Italian organized crime units. More than 9,000 law enforcement personnel obtained in excess of eight tons of cocaine (of which half a ton came from just Finland), two tons of amphetamines, six tons of materials used to make those drugs, and $48 million in assorted cash.

Constitutional interpretation prevented many U.S. arrests

While Operation Trojan Shield was initiated and executed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, an American law enforcement energy, no United States citizens were arrested, let alone prosecuted and convicted, of any illegal acts discovered to have been committed solely through self-incrimination by the perpetrators discussing them on the FBI-controlled ANOM application. Nor were employees of the agency permitted to access or read any messages generated by the service within the U.S. due to strict laws regarding privacy and government surveillance. Citizens of the United States are protected by the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution, which prevents "unreasonable searches and seizures" by the government, requiring that any warrant be supported by probable cause and specifically describe the place to be searched and the items to be seized. That extends to online privacy, rendering the FBI's attempts to infiltrate and break up crime networks domestically moot and illegal.

But courts ruled that some non-American nationals who committed illegal acts discussed on ANOM could be tried in the U.S.. Operation Trojan Shield yielded eight extraditions and 17 indictments in a San Diego court, including Osemah Elhassen, an Australian who also had Lebanese citizenship. He was arrested in Colombia in 2021, extradited to California in 2023, and entered a guilty plea in 2024. Convicted of distributing encrypted devices to known criminals in order to assist in drug trafficking, Elhassen was sentenced to a 63-month prison sentence.

The bust seriously interrupted the drug trade in the Netherlands

Operation Trojan Shield was particularly and notably impactful in the Netherlands. Surveillance on groups and criminals began in October 2019, and 20 months later, it resulted in the arrests of 49 Dutch people when the program ended with a simultaneous sting in more than a dozen countries. In addition to those arrests, 25 facilities used to make and store drugs — whose locations were identified through ANOM communications that Europol and local law enforcement were made privy — were raided and shut down. Eight guns in all were seized as well as an indeterminate but high volume of drugs and ill-gotten currency in the form of 2.3 million euros.

The Dutch wing of Operation Trojan Shield was so efficient because of the involvement of the National Police Unit. Well versed in analyzing encrypted messaging for evidence of criminal activity specifically and cybercrime issues in general, the national agency created purpose-built software for the bust in order to quickly and effectively analyze the millions of messages sent and received over ANOM. The National Police Unit of the Dutch Police then handed over all that information to other European law enforcement agencies and members of Europol.

Australia and New Zealand arrested hundreds of self-implicated criminals

The largest section of suspected criminals arrested with the conclusion of Operation Trojan Shield came from Australia. From the June 2021 bust and all the way until June 2024, the use of the ANOM messaging service on a criminally distributed device led to the capture of 392 people accused of crimes. They were charged for a grand total of 2,355 individual offenses. The main crimes committed were money laundering and drug trafficking, and convictions led to sentencing equal to 307 years of prison time.

On the day of the coordinated international bust, authorities in Australia, where this wing of the project was code-named Operation Ironside, caught 224 suspects and confiscated more than 100 guns and $45 million in cash believed to be involved in illegal transactions. Intercepted messages helped agencies in other countries identify and locate criminals, because ANOM users in Australia had seemingly secretly made business arrangements with organized crime units in Italy and throughout Asia, as well as with motorcycle gangs and global drug trafficking rings. In Australia alone, police were able to prevent 21 potential murders from taking place.

In the nearby nation of New Zealand, 57 ANOM-equipped phones had been distributed over 18 months for the purposes of facilitating crimes. When the sting went into effect, 35 arrests and $3.7 million worth of crime-related assets — vehicles, drugs, guns, and cash — were seized.

A German crime ring was undone by ANOM

With the aid of the FBI as well as Europol, the conglomeration of European law enforcement agencies, police in Germany made upward of 70 arrests in June 2021 as part of the international crackdown on crimes tracked through the ANOM messaging service. Operation Trojan Shield involved searching over 150 separate locations in Germany, with efforts focused almost entirely in the state of Hesse and around its capital city of Wiesbaden. About 1,500 members of various German agencies participated in the dozens of raids of warehouses, offices, and private residences, the locations of which were determined by tracking the data generated by prepaid phones loaded with the ANOM messaging service.

Altogether, on just one day in 2021, German officials confiscated 20 weapons, 30 vehicles, computer equipment, 250,000 euros' worth of cash, and several hundred pounds of illegal narcotics, all of it evidence of crimes committed. Of the 50 drug labs broken up by Operation Trojan Shield operatives, the one in Germany was one of the largest on record in that country's history.