Inside Russia's Doomsday Machine

In the long, tense years of the Cold War, which ran roughly from the end of World War II until 1991, nations across the globe were building up their arsenals, testing nuclear weapons, and spending plenty of time worrying about what the other side was planning against them. The two major nations involved in the simmering conflict, which never technically broke into outright war, were the United States and the Soviet Union. Both engaged in plenty of propaganda and posturing, as well as espionage and economic strikes, but everyone also knew about the terrible power of nuclear weapons.

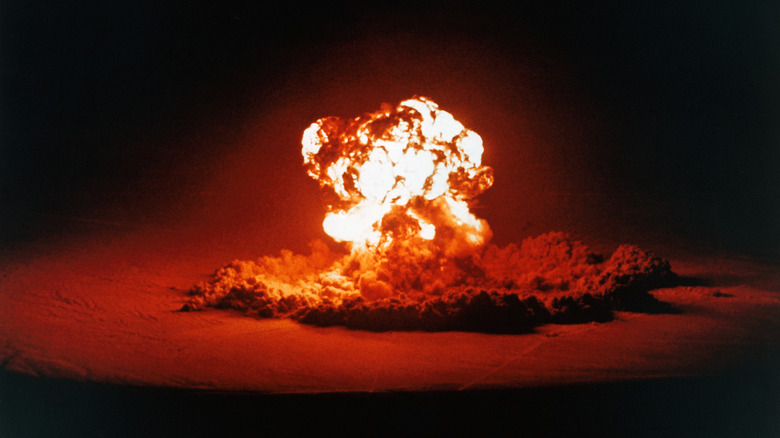

They'd witnessed the effects of nuclear detonations on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which were struck by the Americans in August 1945 and resulted in massive destruction, the immediate deaths of tens of thousands (estimated because of the devastating effects the atomic blasts had on human bodies), and lingering issues like radiation poisoning and increased cancer risks that took ever more lives later.

In short, no one wanted to be hit like that ever again, but neither did they want to be caught without a means to defend themselves. Some Soviet developers began to investigate the possibility of automated or semi-automated systems that would ensure an attack could still move forward, even if a devastating first blow had been dealt by the U.S. Thus was born the Perimeter system, known more ominously as Dead Hand. It's widely known as a "doomsday machine," but many of its capabilities — including its current state of operations — remain shrouded in mystery.

Its roots lie in the Cold War

Naturally enough, the concept of a reactionary, semi-automated nuclear launch system ties back into the Cold War. With the power of nuclear weapons having been demonstrated in devastating fashion on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it was clear to all that a new age of war had dawned. Nuclear weapons even more powerful than those used at the close of WWII were in development and threatened to wipe out major population centers. Of course, everyone was terrified on both sides.

As retired Soviet General Varfolomei Korobushin, the former Deputy Chief of Staff of Strategic Rocket Forces, told an interviewer in 1992, "We were very afraid of the Americans." He noted that, by the 1980s, U.S. actions had become especially alarming to the Soviets, who weren't happy to see increased numbers of Minuteman missiles, mobile airborne command centers, and more missile launch platforms.

That fear led to the development of all sorts of weapons systems, including Dead Hand. Sources indicate that it was first ordered in 1974, though it didn't go online until 1985. By then, U.S. President Ronald Reagan had been doing a fair amount of saber-rattling, though Reagan would have argued that he was only shoring up U.S. defenses and not its offensive capabilities. Still, Reagan's questionable talk of things like a "Star Wars" orbital missile system didn't do much to allay Soviet fears in an increasingly tense technological environment. To those in the know, Dead Hand may have seemed like an increasingly necessary step.

It relies on a basic fail-deadly concept of deterrence

You've likely heard of a fail-safe, in which the breakdown of a system or piece of machinery automatically reverts it to a relatively safe state. Dead Hand, however, was predicated on the much more ominous "fail-deadly" concept. As the name implies, a breakdown in such a system would still allow for deadly retaliation.

In the case of Dead Hand, its activation meant that any lapse in that communication, along with other factors like detected nuclear strikes, would transfer control of the nation's nuclear launch system to that bunker's personnel. Those people could choose not to launch the missiles, but certainly the intent is to allow for deadly retaliation even if part of the Soviet system "failed" after being hit by an enemy strike.

The fail-deadly scenario is effectively a component of mutual assured destruction. This infamous facet of Cold War strategy is a kind of deterrence in which both sides in a conflict have a considerable array of nuclear weapons; so considerable, in fact, that both sides have the capability of completely obliterating the other. If one power were to attack, the other could potentially launch a just-as-deadly counterattack that would leave both sides in irradiated cinders. The Dead Hand twist on this scenario is that the U.S.S.R. would have been able to engage in mutually assured destruction even if the U.S. had been able to hit it with a decisive, devastating strike first.

Despite the terrifying name, Dead Hand is theoretically designed to prevent mistakes

The whole concept of Dead Hand, in which a Soviet Union brought to its knees by a deadly strike could still wreak nuclear vengeance, is obviously terrifying. But there is a silver lining built right into the system's design. It could theoretically give decision-making officials mental space to think. In a time of looming crisis, they could turn on Dead Hand but not immediately launch anything, psychologically buying more time for top-level discussion and identifying false alarms, and keeping the Soviet government from jumping the gun in horrifying fashion.

Those sorts of mistakes can happen, as in the 1983 incident where a Soviet early warning system claimed to detect evidence of incoming nuclear missiles. Lt. Cl. Stanislav Petrov, an officer in the Air Defense Forces, was on watch duty when the warning came in, but intentionally failed to alert higher-ups to narrowly avoid the end of the world. His informed guess that it was a false alarm paid off — the system had misidentified the sun's reflection off clouds as missile exhaust. Petrov would later explain to reporters that the whole thing was kept quiet because such a system failure was considered shameful.

Though Dead Hand was in development at this time and not active, it's easy to understand why its system was considered an improvement. A possible mistake, such as the 1983 false alarm, would be able to pass so long as no signs of nuclear explosions were detected.

Dead Hand would sense signs of a nuclear strike before engaging its program

One of the key components of the Dead Hand system is its ability to detect the signs of a nuclear strike before following through on the rest of its programming. That would be cold comfort to anyone living in a potentially vulnerable area, such as Moscow, but it would at least potentially avert a global nuclear war that could take many, many more lives.

After being turned on by command during what had been deemed a crisis period, the system would then wait for signs of an actual attack. As for what it was specifically meant to be looking for, retired Soviet General Varfolomei Korobushin said in his 1992 interview, Dead Hand "would have been triggered by a combination of light, radioactivity, and overpressure." If these were all detected together and at presumably high-enough levels, the system would assume some sort of strike had happened.

Such signs of a nuclear detonation are hardly going to be promising, but Dead Hand was meant to then wait for some amount of time for contact from command in Moscow. Too long without hearing from them, and the system would assume that the signs of a nuclear attack it had just sensed were the real thing, and not a false alarm triggered by atmospheric conditions, flocks of birds, a confused bear (a real problem for one American base in 1962 Minnesota), or any number of other unforeseen factors (aside from other worrisome related events like the time the U.S. lost its own nuclear weapon).

The system is actually semi-automatic

A quick scan of the Dead Hand system may lead you to believe that it's largely free from human influence, like the deadly computer with its digital hand on a very real switch in "WarGames." Yet, as far as Dead Hand is concerned, there's definitely a human element involved that may make you grateful.

Yes, quite a lot of the system appears to be automated, with computers taking care of major steps like detecting the signs of a nuclear strike, communicating (or not) with officials, and transferring power. But there are at least two known points where living, breathing humans must ferry that process along. At the very beginning, someone's got to activate the system, as sources indicate that Dead Hand is normally left in the "off" position. At that point, it automatically runs through four major "if/then" propositions. If it's been activated, then Dead Hand is looking for signs of a nuclear strike. If those signs are detected, then it checks communication links with command. If communications are clear and no further signs are detected, then Dead Hand assumes someone's still alive to make the relevant launch decisions and stands down.

If nuclear weapons really have gone off and Moscow or some other predetermined center of power has gone eerily silent, then Dead Hand automatically transfers command to humans somewhere else. The final decision to launch is then in the hands of either a group of people or, perhaps in an especially dire situation, just one individual.

Dead Hand was not always switched on

The idea of Dead Hand just sitting there and waiting for an excuse to fling nuclear missiles at the U.S. may beg all sorts of unnerving questions, but it's not always "awake." As retired Soviet General Varfolomei Korobushin made clear in his 1992 interview, "The system is not on. It is to be activated only during a crisis."

But what's a crisis? It's not immediately obvious what situation the Sockets or their Russian Federation successors have deemed to be worthy of activating Dead Hand. Is there a checklist somewhere, or is it meant to be a decision made on a case-by-case basis? And while we know that Dead Hand never followed through to its grim endpoint during the Cold War, neither is it clear how many times it was activated. Perhaps most concerning is that few people know who would have been in that mysterious command bunker. Was or is there always a high-level commander with some in-depth knowledge of the situation and its geopolitical implications? Or would it have ever possibly been a scared young officer who, with very little input or background information, had to make one of the most monumental decisions in human history in mere minutes?

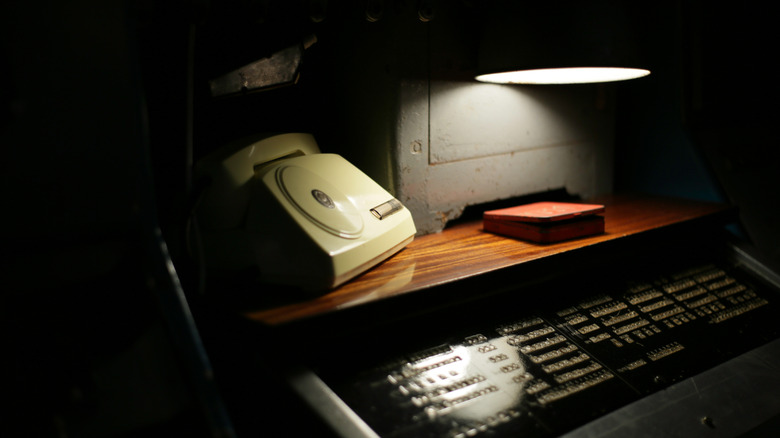

It's not entirely clear where the command post is

While the Soviet Union and now Russia has been pretty tight-lipped about the exact parameters of Dead Hand, we have the general idea that it can transfer control of the nuclear armament to staff in a bunker. But where is that bunker, exactly? Even the most talkative people who have disclosed their insider information to journalists and other observers haven't really said.

Still, there are hints. Given the scenario in which such a bunker would become very, very important, it's all but certain that this location is very heavily shielded. A 1993 report by The New York Times wondered if it was somewhere south of Moscow, but U.S. intelligence instead concentrated on mountains in the Ural range to the east of Moscow. Both the Yamantau and Kosvinsky peaks hosted mysterious large-scale construction projects in the 1970s, when increased U.S. weapons capability allegedly pushed the Soviets into action. Reportedly, satellite imagery showed work continuing on both sites into the late 1990s, well after the fall of the Soviet Union.

The Kosvinsky facility may be the most obvious candidate, as it's said to have the ability to communicate over far distances with very-low-frequency radio that could work even in an atmospherically chaotic post-detonation environment. Bruce G. Blair, a former U.S. military officer with launch control experience and nuclear security expert, told Slate that, based on his contacts with Soviet officers, he believes "The facility is the critical link to Russia's 'dead hand' communications network."

Dead Hand can't be a first strike option

If it hasn't been made clear already, the Dead Hand system simply cannot function as a viable preemptive strike option. In fact, it appears that for much of the Cold War, the Soviet Union didn't really consider this to be a good strategy, perhaps because they weren't always confident that their arsenal and launch systems were up to the task. A declassified CIA report from 1973 bluntly states that "There is good evidence that the Soviets do not consider a sudden first strike to be a workable strategy." However, that didn't necessarily stop U.S. analysts from worrying that all the talk of avoiding a first strike was just propaganda.

With Dead Hand, it seems that the Soviet military strategy really was built largely on avoiding first strikes and only activating the system as a retaliatory measure. Retired Soviet General Varfolomei Korobushin told an interviewer in 1992 that they had even planned to destroy their arsenal in other situations. "In case of a conventional attack against us, we always planned to destroy all our missiles and silos, rather than use them to launch missiles," he said. "We had on hand mines and destruction devices which we would have emplaced in our silos if they were ever in danger of being overrun."

He further stated that, from a military perspective, "all of our calculations for force building were based on the scenario of the retaliatory-meeting strike, not on the idea of deterrence."

Dead Hand could still be prepped under the Russian Federation

While much of the information outsiders have about the Dead Hand system comes from the Soviet Era, the U.S.S.R. had collapsed by the end of 1991. But it stands to reason that Dead Hand lives on in some form or another. Certainly, when he wasn't busy trying to hide other secrets, Russian President Vladimir Putin repeatedly reminded world leaders of his nation's nuclear capability, and has officially taken on the strategy of "de-escalation," in which a major attack could be met with a limited use of nuclear weapons in an attempt to get everything back to its previous geopolitical state.

However, no one's been able to get any definitive word out of officials regarding Dead Hand's current status. In August 2025, after American President Donald Trump spoke of the "dead economies" of India and Russia, former Russian President Dmitry Medvedev responded in a chilling (but mildly confusing) fashion. As he stated on social media app Telegram, Medvedev wrote that "As for the talk about the 'dead economies' of India and Russia, and 'entering dangerous territory' – maybe he should recall his favorite movies about 'the walking dead,' and also remember how dangerous the so-called 'Dead Hand,' which doesn't even exist, could be" (via NDTV).

On the surface, that statement makes it sound like Dead Hand is no more, but it didn't exactly reassure anyone. Certainly not Trump, who responded by ordering two nuclear submarines to move closer to Russian territory.

The oddest thing about Dead Hand may be the secrecy

While hardly anyone expects Vladimir Putin to just stroll out of the Kremlin and give the nearest bystander Dead Hand blueprints, it is a bit odd that there's been quite so much secrecy about the system. Though it was ordered in the 1970s and put online in the mid-1980s, system developer Valery Yarynich writes in "C3: Nuclear Command, Control, Cooperation" that it wasn't officially acknowledged until 1999. Even then, despite consistent writing about Dead Hand since the early 1990s, it never quite made it into the larger public consciousness. Even a former CIA director interviewed by WIRED in 2009 was shocked at the prospect, telling reporter Nicholas Thompson that "I hope to God the Soviets were more sensible than that."

It is perhaps even odder when considering the Cold War stalwart of nuclear deterrence. The whole concept relies on one's enemy knowing what you're capable of. While the Soviet Union obviously wouldn't want to give the whole thing away, a bit more publicity could have helped tamp down American aggression and those nuclear fears. Perhaps it was deemed too much of a risk, whether that was in terms of security concerns or worries about inflaming an already-tense relationship between the two heavily armed superpowers.

The US and the UK have had similar systems

Other nations have considered fail-deadly scenarios, like the U.K.'s postwar take on the concept in its C3I system. C3I is a military abbreviation (sometimes simply C3) that refers to command, control, and communications – all vital to someone making decisions before, during, and after a nuclear attack. In the case of Britain, its C3I was designed to "fail deadly" in case of a Soviet strike, even though its comparatively small military resources made some worry that the system might not work and could lead to further escalation. Ultimately, the British worked in cooperation with American forces under the NATO umbrella, coordinating nuclear strategies but allowing room for the U.K. to retaliate if push came to irradiated shove.

Some have argued that President Eisenhower's orders to ramp up U.S. nuclear armament and engage in nuclear deterrence meant his government was engaging in some form of "fail-deadly" preparation, in case the Soviets or other foreign powers weren't sufficiently scared of American capabilities. But the U.S. also took on projects more obviously like Dead Hand, including the implementation of sensors that could detect nuclear detonations and a network of linked missiles tipped off by command rockets, known as the Emergency Rocket Communications System.

However, the U.S. relied on service members in Strategic Air Command airborne command posts to give a theoretical launch order. This project, in the air from 1961 until 1990, was called Looking Glass and was more out in the open, in the spirit of nuclear deterrence.