How Bootleggers Fueled NASCAR

In the 21st century, spectator sports are big businesses that are popular around the world. They're such elaborate enterprises involving so many venues and people that it's hard to imagine their humble beginnings. And all of them — football, baseball, basketball, and even stock car racing — started out with a bunch of guys messing around. The team-oriented ball sports began in a field or gym as low-key athletic games, but stock car racing, the American-made sport of pitting fortified and specially engineered cars against one another on an oval track in events that last the equivalent of hundreds of miles, started in a much more roguish and extraordinarily illegal manner.

Long before the historically important Daytona 500 became an annual happening, NASCAR was officially launched in 1949 by Bill France Sr. and many associates. Since then, it's served as the playing field and employer for dozens of legendary athletes, like Richard Petty, Jeff Gordon, both Dale Earnhardts, and a bunch of race car drivers who are really weird people. It all seems very pure, racing cars and seeing which driver can go the fastest. But the history of NASCAR goes back directly to bootlegging — the production and transport of alcohol when it was against the law during Prohibition. Here's the story of the criminal and booze-aided origins of NASCAR.

Drivers earned their chops running from the cops

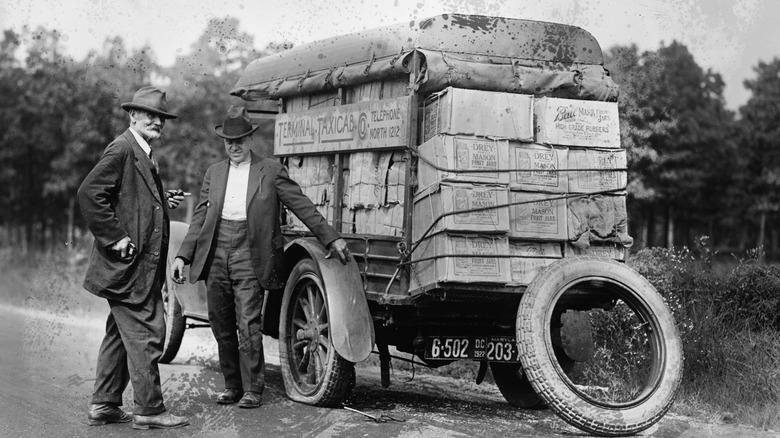

It's a big part of the truth of Prohibition that when the U.S. federal government ratified the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which went into effect in 1920, it led to the rapid growth of organized crime. The production, sale, and distribution of alcohol was suddenly illegal, and in major Northern cities like New York and Chicago, Italian-American Mafia-associated crime rings stepped in to keep the booze trade going in a clandestine manner. In the Southeastern U.S., the approach to uniting citizens with the liquor they wanted, despite the blanket ban, meant the rise of bootlegging networks. Making homemade liquor, like extraordinarily strong and potentially dangerous spirits distilled from corn, was a very old process, and Prohibition encouraged humble distillers to scale up their efforts to make and distribute their product across their state or region. Moonshine had to be transported across distances via automobile by drivers known as whiskey trippers.

The American South is characterized by large expanses and hilly, mountainous areas where the roads are curvy, treacherous, and demand care and attention from drivers going the speed limit, let alone those trying to avoid detection or lose police or federal agents in hot pursuit because they were carrying illegal product. In the 1920s and 1930s, making their cars go as fast as possible because they were loaded up with contraband created the driving culture that would one day coalesce into professional stock car racing.

Modified NASCAR cars are an outgrowth of bootlegging times

To move the moonshine, whiskey trippers had to be assured that their vehicles could make a clean getaway. Crafty drivers altered their cars, primarily stock models made by major American automobile manufacturers. They needed more speed and power from their vehicles than did the average commuter, and bootleggers conspired with mechanics to get their cars to go a little bit faster, or to offer just a little more power or better handling on challenging country roads.

Those modified automobiles are the predecessors to the expertly engineered, super-fast NASCAR vehicles of the late 20th century and beyond. It was bootleggers who popularized the idea of dramatically modifying cars. To avoid having the car weighed down so much by a load of moonshine that it experienced a reduced top speed, mechanics would add heavy-duty suspension parts to their car's machinery. They also might remove the vehicle's interior components to reduce weight and make more room for moonshine. Steel plates drilled into radiators protected the engine from pursuant police gunfire, while exterior compartments to dump oil or nails on the road to slow down authorities' cars were also fairly common. Today's NASCAR machines are as aerodynamic as possible, with no unnecessary parts or sources of drag. That's not too different from the bootlegging-era practice of taking off windshield wipers and covering the spaces around headlights.

Before NASCAR, bootleggers raced their transport cars

By the early 1930s, moonshiners' cars had so become the stuff of legend — built with essentially homemade ingenuity that outsmarted and outgunned local and federal authorities — that the vehicles came out of the shadows. Fairgrounds and racetracks, which had previously been used for all sorts of competitive events, motorized and otherwise, became the site of moonshine car contests. When they weren't on whiskey runs, drivers in places like Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia would gather to see which one of their cars that had been modified to be tough and speedy was the toughest and speediest of all.

As it turns out, that was something the general public really wanted to see. Early amateur stock car races drew big crowds of spectators eager to check out the customized cars and their daring operators. When Prohibition ended in 1933, that gave stock car racing an air of legitimacy. No longer did bootleggers have to keep their souped-up cars secret if they didn't want or need to. Those vehicles, modded out of necessity for the job at hand, could now exist solely for racing.

Bootlegging continued after Prohibition

Deeply unpopular with the nation and responsible for a rise in crime, Prohibition was repealed by the federal government by way of the 21st Amendment. As of December 1933, booze was legal again. But that didn't spell the end of moonshine production, nor drivers distributing it around the backroads of the Southeastern U.S. in their jacked-up automobiles. The alcohol industry had been legitimized on the federal level, but its products would be subject to stiff taxes and excises. For the bootleggers who got into selling their homemade booze as a significant income source when they were economically struggling, things only got worse when the Great Depression hit in the 1930s. Under Prohibition, there was no taxation on illegal goods; without it, there was, and that threatened their livelihoods. "Moonshiners didn't want to share the tax revenue or any of this enterprise they had built from scratch," NASCAR historian Neal Thompson told History.

And while the 21st Amendment legalized alcohol on the national level, local governments could still decide whether or not to allow the sale or production of booze in their jurisdictions. Seeking to curtail the perceived crime or moral turpitude associated with the consumption of alcohol, many counties in the South remained "dry" after Prohibition. For whiskey trippers making moonshine or traversing those places in the 1930s and 1940s, it was business as usual, and they kept using their very fast, very powerful cars to race on through.

The automotive breakthrough that helped bootleggers and auto racing

One automobile manufacturer's innovation in particular made running alcohol a lot easier for bootleggers and their drivers. That, in turn, made organized and codified auto racing through groups like NASCAR happen much sooner than it otherwise may have.

In 1932, Ford introduced the V-8 engine. One such engine was used in the car that made possible Bonnie and Clyde's crime rampage around the same time, and the machinery was favored by plenty of law-breakers who needed to make quick getaways from law enforcement — such as drivers hauling carloads of illegal or untaxed liquor.

What made the V-8 so special was that it provided power and strength as well as speed. The installation of such an engine turned a regular automobile into one of the fastest commercially available vehicles, capable of speeds exceeding those of standard-issue police cars. It could also handle a lot of wear and tear without sacrificing performance, meaning it handle booze runners' demanding courses of twisty, rocky mountain roads. Additionally, the first Ford cars that came with V-8 engines were larger models that promised roomy trunks and backseats where drivers could haul even more moonshine than before. Those V-8 engine-outfitted Ford cars were some of the fastest and most rugged ones in the South in the 1930s, making them a natural choice for drivers to race on the amateur circuits that preceded NASCAR.

When runners became racers

As more races took place and bootlegging continued, the cars involved grew more sophisticated, which attracted more drivers — and an audience. As the 1930s wore on, stock car racing had divorced itself from bootlegging to the point that events could be staged that were open to the public in high-profile, high-capacity venues. In 1936, the Daytona Beach Road Course in Florida hosted the first official stock car race for paying customers. Two years later, a whopping 20,000 people showed up at the Lakewood Speedway in Atlanta to watch what's considered the first major stock car race.

Development in the sport slowed considerably during World War II, but stock car racing picked up again in 1945. That year, after a near-riot broke out at Lakewood Speedway when local police prevented five drivers from competing, those individuals were allowed to race. The reason for the almost-expulsion: They'd all been previously convicted on charges related to bootlegging and liquor running.

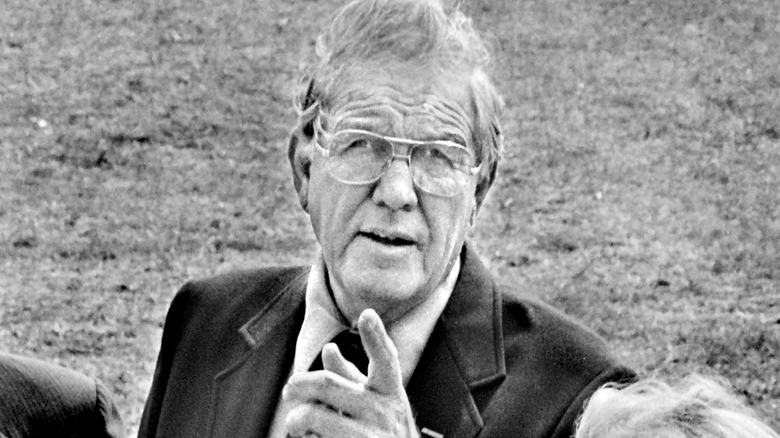

While Atlanta had been a major area for bootlegging and thus early stock car racing, the 1945 incident at Lakewood made the circuit unwelcome in the city, prompting a move to the Carolinas and Virginia. That's where driver Bill France Sr. (pictured) compiled a a group of drivers, mechanics, and private funders to race their vehicles, many of whom had been employed for the purposes of bootlegging. In 1947, France lead a group that wrote up the rules that would govern the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing, or NASCAR, which got underway in 1948.

A major bootlegger became a NASCAR champion

Born in Georgia in 1914, Raymond Parks (pictured) was arrested as a youth and served three months behind bars for the crime of attempting to purchase corn whiskey for his father. Then he doubled down on the Prohibition-era illegal alcohol industry, striking out on his own at 14 to work for a bootlegger outside of Atlanta before starting his own liquor-running business, ferrying contraband from his hometown of Dawsonville to businesses in Atlanta, about 60 miles away. Business boomed, and before long, Parks oversaw numerous drivers of cars that had been modified to go faster so as to outrun police if they were ever caught for speeding or transporting alcohol. So many counties in the South continued to keep alcohol illegal after Prohibition ended, that Parks' business remained intact. Eventually, he was busted and spent nine months in federal prison in the mid-1930s.

Parks invested his liquor money in some legal ventures, like vending machines, jukeboxes, and sponsoring drivers who built up their cars to compete in amateur races around the South. He footed the bill to form NASCAR in the form of loans to the organization's official founder, Bill France Sr., and Parks was present at the Daytona Beach, Florida, meetings that established the league in 1947. Credited as the first NASCAR team owner, Parks funded and encouraged two early champions: 1948 modified division winner Fonty Flock and 1949 stock winner Red Byron.

A bootleggers' mechanic became an instrumental NASCAR figure

Louis Vogt, better known as Red Vogt, began working on cars professionally in 1915. The 11-year-old got a job as a mechanic at a Cadillac dealership in Washington, D.C. In his free time, he and close friend (and future NASCAR head) Bill France raced cars and motorcycles. While Vogt would win motorcycle racing titles in four straight years by the 1920s, he was seriously hurt in two crashes, knocking out most of his teeth in one and getting shards of racetrack wood stuck under his skin in another.

After Prohibition was underway, Vogt moved to Atlanta, where illegal alcohol manufacturing and distribution operations had been thoroughly established. There he got back into working the other side of the wheel, building and maintaining high-end cars. Being a bootlegger during Prohibition required a fleet of automobiles for transporting alcohol long distances, and an Atlanta booze magnate named "Peachtree" Williams hired Vogt to build, repair, maintain, and fortify his delivery vehicles. Such were his talents and innovations that other bootleggers soon sought him out. Vogt's cars were durable and fast, and two of his first clients were moonshiners "Lightning" Lloyd Seay and "Rapid" Roy Hall. When they moved into stock car racing, they brought along Vogt as their trusted mechanic. Vogt's skills were so heralded that he was present for the first NASCAR championship in 1948, and he's credited with coming up with the name, the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing.

Numerous drivers previously hauled liquor

NASCAR's ranks were at first populated with drivers with extensive experience in bootlegging all over the South, because they were the guys who had the fastest cars and knew how to properly operate them. Curtis Turner (pictured) started making hooch at the age of 9, and he claimed he'd made a million bucks by the time he hit 20. In the inaugural NASCAR Strictly Stock Series races in 1949, Turner finished in sixth place, and he'd win 17 events over a 20-season career.

After serving in World War II, Wendell Scott became a mechanic and moonshine runner, operating out of the hooch hotbed of Franklin County, Virginia, in the Blue Ridge Mountains. He began racing stock cars in 1952, winning 120 races before he moved up to NASCAR, becoming the organization's first Black driver.

Future Motorsports Hall of Fame of America inductee Tim Flock followed his brothers into bootlegging. They were employed as alcohol distributors in rural Georgia, and Flock loaded their cars with crates of moonshine. Tim Flock specialized in long distance runs, making deliveries between Atlanta and Alabama. In 1939, Bob and Fonty Flock took the very same Ford Coupes they'd used to run moonshine and entered them in a 100-mile race at the Lakewood Speedway in Atlanta; they lost to bootlegger Roy Hall. By the late 1940s, all three "Flying Flocks" were among auto racing's earliest stars, and flagship members of NASCAR.

A NASCAR founder was a bootlegger

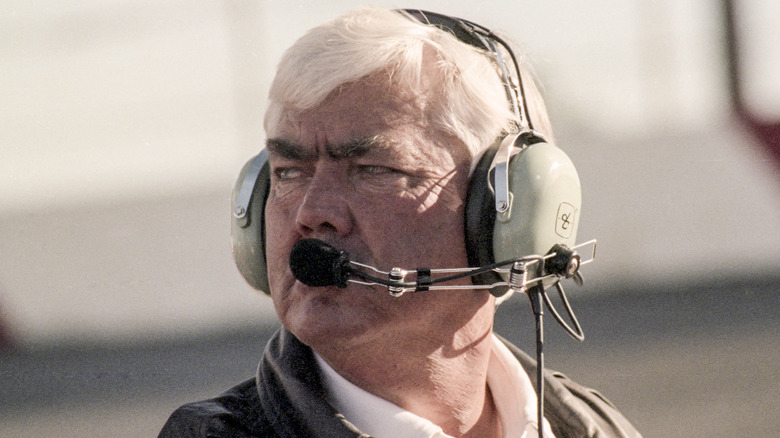

Junior Johnson's family had been making moonshine since the late 1800s. In 1935, authorities seized 7,000 gallons of illegally made whiskey from the Johnson farm in North Carolina, the largest bust of that nature ever at that time. When he came of age, Johnson's driving skills came in handy — he could make booze runs for his father. "Moonshining was part of my growing up, but it was also part of my training in auto racing," Johnson explained to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1990. "You had to have fast cars to haul your whiskey to the people and to get away from the revenue and the ABC and the federal officers," he told the BBC, referring to the post-Prohibition environment in which he ran booze while eluding tax agents and the Alcoholic Beverage Control. "If it hadn't been for whiskey, NASCAR wouldn't have been formed. That's a fact."

Johnson (pictured) was reportedly such a speedy and evasive driver that he was never captured by police on any of his moonshine deliveries. That translated to a tremendous aptitude for formal auto racing, and he made his NASCAR debut in 1953. In 1956, after he was already a star in his sport, Johnson was arrested and convicted on charges relating to running an illegal alcohol-producing still. A similar device sits on the NASCAR Hall of Fame's Heritage Speedway, constructed and donated by Johnson, one of the first people inducted into the facility in 2010.