What It Was Really Like Being A Bootlegger During Prohibition

For every good idea a man or woman has ever had, it seems like there were at least a hundred really dumb ones. Some of those ideas didn't just languish in a corner until they faded into the shadows, as they should have — some became dumb mistakes that impacted the course of history.

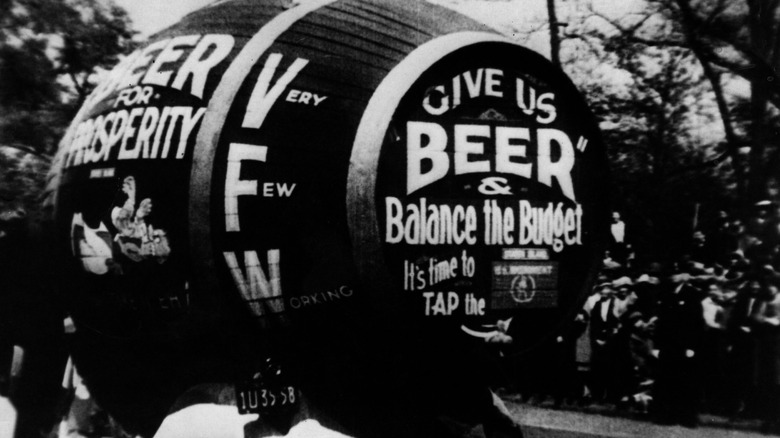

Prohibition was definitely one of those dumb ideas. It was driven by the temperance movement, which preached about the evils of alcohol and tried to convince people that the occasional drink would lead to things like spontaneous combustion and genetic defects that would be passed on through generations. They were a fun crowd.

Regardless, Prohibition got passed — for a bunch of reasons — but there were a whole lot of people who decided they weren't going to stand for any of that. They were, of course, the bootleggers.

The term bootlegger can be used for anyone who produced, transported, or sold liquor while it was illegal under the incredibly unpopular 18th Amendment of the United States Constitution. What was it like to break the law for the sake of a drink? Let's find out!

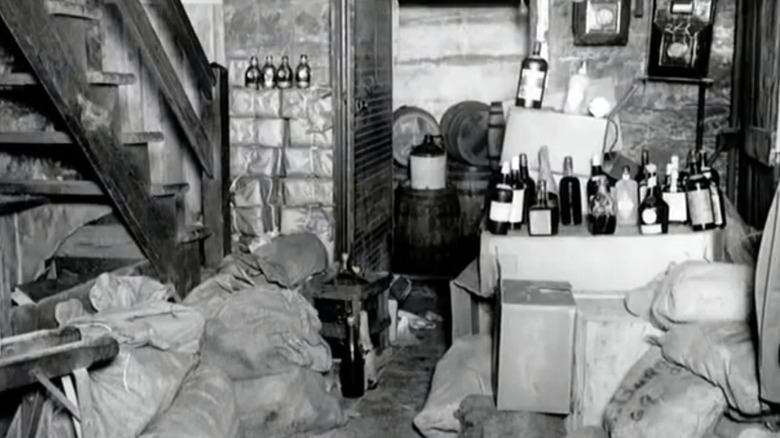

There were little operations, and big ones

When it comes to bootlegging operations during Prohibition, there was no one-size-fits-all job description. The Mob Museum says that some bootleggers were tiny family businesses with a few industrious people making liquor by the gallon in personal-size stills. This is where the idea of bathtub gin came from — it wasn't gin made in a bathtub but gin made using the bathtub faucet.

Some families worked together with small-time mobsters supplying their kit. The Genna gang in Chicago, for example, supplied the stills and raw materials — along with a daily stipend — to families who made the liquor they collected and sold.

Then, there were the giant operations. Legendary bootlegger Al Capone alone ran a massive, multi-million dollar booze and gambling empire with countless people on his payroll, and History says he pulled in between $60 and $100 million a year just in the alcohol trade. This wasn't a small-time, low-key distillery set up in a few basements — it's been described as a paramilitary organization, with everything from bribery and threats to outright violence used to make a lot of booze and a ton of cash.

There was a massive number of bootlegging trade routes

There were many different kinds of bootleggers. After all, wherever there are people, there are people who want a drink. During Prohibition, bootleggers were found all across the Good Ol' US of A, with hot spots in cities including Chicago and New York.

Not all illegal liquor was made in the country, and there were a number of illicit trade routes bringing in booze by land and by sea. Whiskey was a major import and often came to the east coast and Gulf Coast from Great Britain via — appropriately — the olde-timey pirate capital of Nassau. Canada was another great source, with illegal shipping routes from British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Ontario, and through Nova Scotia and St. Pierre.

It was secret, sure, but it wasn't top secret. The biggest, baddest, non-secret was Rum Row, a line of big boats anchored in international waters along the east coast. They transferred their goods to lighter, more mobile crafts called contact boats. According to The Mob Museum, bootleggers also used souped-up cars, sailboats, schooners, and even school buses. Vehicles of all kinds often had hidden compartments and, sometimes, came with a child or two to help throw law enforcement off the scent.

Sometimes, you just fall into being a bootlegger

So, how exactly did someone get into the business? There was no application process or even a guild. People got into bootlegging in ways as varied as the practice itself.

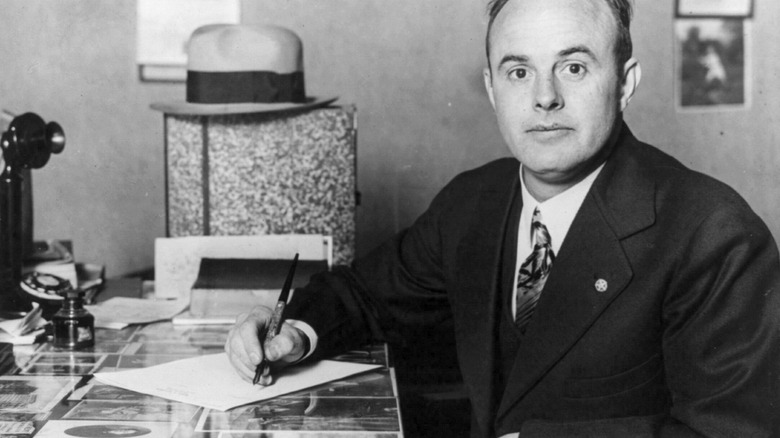

Let's take a couple examples, starting with George Cassiday. Known as The Man in the Green Hat, the U.S. Senate says Cassiday became a bootlegger servicing a very select market: the U.S. Capitol, including Senate and House members who had voted in favor of Prohibition. He kind of fell into the gig. Upon returning home from World War I, a friend asked him for a few bottles of liquor for a pair of House representatives. It snowballed from there, and pretty soon he was making 25 deliveries each day, all in his trademark green hat.

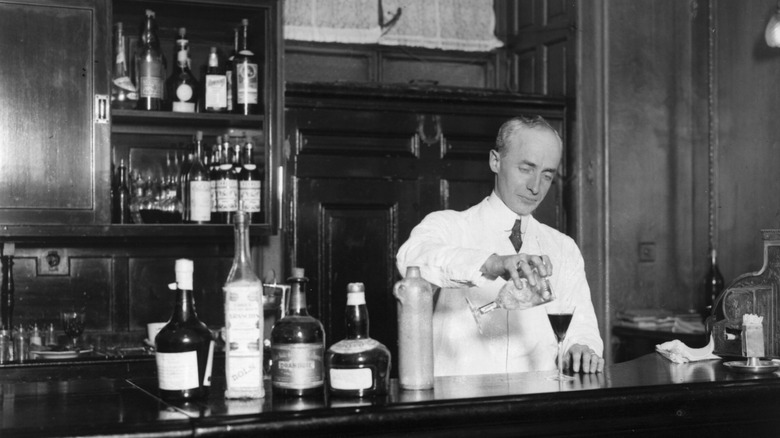

Others seemed to fall into the business too. In 1926, an anonymous bootlegger penned an article for the New Yorker, explaining that he had been working as a waiter for years before Prohibition suddenly made times very tough. Until, that is, the doorbell rang. The man on his step "just laughed and said one of my very good friends had sent him to see me," the future bootlegger revealed. The man said he knew a guy who had the goods, the one-time successful waiter had the contacts, and guess who was working for who now?

You needed to be able to pull off a good swindle

Being a successful bootlegger wasn't just about the making and selling of alcohol — the really successful ones needed to be part con man, too.

An anonymous bootlegger wrote an expose for the New Yorker, saying that real Scotch would be watered down and that even when quality of liquor deteriorated, he wouldn't lower the price for fear of customers realizing they were not getting the best goods. He wrote, "As long as they were paying higher prices for their liquors than their friends, I knew they would think they were getting better stuff." One of his higher-ups in the distribution chain explained it this way: "Of course, we are not delivering genuine Scotch liquor or genuine anything else. We cannot get that stuff any longer. ... But, of course, the customer ... likes to think that he is getting the real stuff. And ... it helps business to make him think so."

It was all in the experience — some bootleggers discovered that using the same bottles as big brands with reproduction labels would allow them to charge top dollar for "the real thing," even if the contents had been made unprofessionally. The anonymous source explained, "People seem to have lost their taste, as far as liquor is concerned. They can't tell the genuine article from a good imitation any time."

You'd better be ready to name-drop

Getting busted kind of went along with the territory when it came to being a bootlegger. But there was often a benefit in being part of a larger crew — the higher-ups tended to take care of the guys doing the dirty work. Take Al Capone, for example. History says he spent a whopping half a million a month just paying bribes to everyone from law enforcement to politicians, and that went a long way in keeping the booze flowing.

In a 1926 piece written for the New Yorker, an anonymous bootlegger revealed that he was often given a name to drop as a sort of get-out-of-jail-free card. He was told the name of a "big politician [who was] very much respected by every cop I ever met" — but only needed to use it twice. Once was for one of his employees, who was stopped while making a delivery, and the second was for himself. In the latter incident, he was heading to Montauk Point with a car full of whiskey when he was stopped by uniformed police. After openly admitting that the car was full of liquor, he dropped the name. The two officers called back to New York, confirmed that the bootlegger was associated with this influential man, and waved him on his way. At the next town, he was pulled over again but just told not to drive too fast or he'd likely be picked up by a cop who wouldn't understand.

You could buy supplies from the local grocery store

Some bootleggers went the independent route and made their own booze from scratch, and it wasn't as difficult as it might sound. Why? A lot of the equipment and ingredients could be bought at the neighborhood grocery store.

According to The Mob Museum, law enforcement confiscated around 697,000 stills between 1921 and 1925, and a lot of those had been purchased from local hardware stores or assembled from widely available parts.

Buying the raw materials was easy too. Corn, hops, and corn sugar were widely available in bulk. So was malt syrup, a popular ingredient in homebrewed beers. Anyone could walk into a grocery store — including A&P and Kroger — and buy cans of it. The higher the demand, the more the supply chain ramped up. It's estimated that by 1927, enough malt syrup had been made to allow enterprising homebrewers to make about 6 billion pints of beer, give or take.

Wine wasn't any more difficult. According to Smithsonian, many vineyards and wineries started manufacturing wine bricks during Prohibition. These were grape juice concentrate that came with written "warnings" about how consumers should absolutely not dissolve the concentrate in water then keep it in a cool, dark place for 21 days. That would make wine, which certainly wouldn't be the intention, would it?

Bootleggers literally went underground

Anyone hoping to make it as a bootlegger in a big city would have to have no problems with claustrophobia. Many big-city bootleggers relied on the secrecy afforded by tunnels to get around, so they had to be comfortable in cramped, dark spaces.

Take Chicago. Northwestern University professor Bill Savage says (via Mental Floss) that many of the buildings were built with interconnected basements — not tunnels per se, but underground passages that were useful for moving liquor and as escape routes during police raids. The Uptown tunnels are one example. This network of passageways connects the Green Mill Cocktail Lounge, and possibly several theaters including the Uptown Theater and the Aragon Ballroom, as well as other businesses in the city's North Side.

KCET says there are similar tunnels under Los Angeles. They were originally built for underground trolley cars, but by the time Prohibition rolled around, the cars weren't running as much, and bootleggers made good use of the tunnels.

Interestingly, when Prohibition went nationwide in 1920, North Dakota had already been a dry state for 31 years. With this history, it's not surprising that Minot had a jump on the nation, with underground tunnels and secret rooms scattered across the city. Traveling Midwestern says many were only revealed during a 2011 flood, alongside some jars of moonshine that had been hidden for a very long time.

Bootlegging took some serious driving skills

The Mob Museum says that the early 1920s were the golden years of rumrunning, because after that, law enforcement started to catch up and made bootleggers' lives much more difficult. Consequently, bootleggers couldn't just be okay drivers — they had to be really, really good no matter what they were driving.

Smithsonian reports that vehicles were often outfitted with heavy-duty shocks and springs to prevent the booze from breaking on bumpy mountain roads. The seats in the back were often removed to make room for more alcohol, and engines were modified to make it easier for bootleggers to outrun cops. Negotiating narrow dirt roads at night with no lights is bad enough, but add in the extra weight of the liquor and the need to handle punctured tires and any other mechanical problems that might happen without drawing attention, and it's definitely not a job just anyone could handle. It's no wonder that NASCAR was born from bootlegging.

According to Defense Media Network, the fledgling Coast Guard added hundreds of boats to its fleet during Prohibition, and bootleggers needed to take extra precautions. It wasn't long before cargo wasn't carried on boats but dragged behind in case it needed to be dumped quickly. Add in the fact that these boats were often moving through shallow waters and rocky shoals at night with no lights, and the need for evasive maneuvers like setting fuel on fire in the boat's wake at any second, and it's easy to see how boat pilots needs to be really good at what they did.

You couldn't stay little

There's something romantic about the notion of the little guy making his backyard hooch and selling it on down the road to make a living for himself and his family, but as Prohibition rolled on, that was less often the case.

Take Rum Row, the line of ships that floated just off the coast and provided a supply of booze via contact boats. Defense Media Network says that when Prohibition was implemented, the recently created Coast Guard was sorely out-gunned by dozens of big ships and even more contact boats. (In an instance of "We should have seen that coming," many of the contact boats had motors that had been sold by the government as surplus after the war.) But later, the Coast Guard got an upgrade and by the later years of Prohibition included over 10,000 officers and 25 re-assigned naval ships.

About the same time, many small-scale bootleggers found themselves fighting a losing battle. The rise of organized crime meant that many of the independent brewers and distillers were being either welcomed into the fold, run out of business, or worse. Not all bootleggers saw being connected to a larger organization as a bad thing. When the anonymous author of a 1926 piece for the New Yorker talked about the big boss who brought him into a larger organization, he said, "He would guarantee me protection. ... he would show me how to expand my business. ... It was my first step toward really big business in the bootlegging industry."

It wasn't a case of us vs. them

There are huge sections of bootlegging history that are, of course, undocumented, but "Smugglers, Bootleggers and Scofflaws" recounts enough recorded incidents to make it clear not all bootleggers banded together on the same side against Johnny Law.

Piracy was not uncommon, and sometimes it turned bloody. Incidents include a boat captain who was robbed of tens of thousands of dollars' worth of whiskey off the coast of New York and a boat crew who ended up washing up on Martha's Vineyard after (authorities believe) their boat had been rammed and their cargo stolen.

Stakes were incredibly high. In another well-documented example, American bootleggers took the agent of a French ship to Manhattan for a night on the town while their associates headed into the waters, took the French crew hostage, and spent the next 10 days stealing a whopping $800,000 worth of liquor from the ship using 10 small boats.

New Yorkers were also behind an incident in which a British ship from the Chelsea Trading Company had about $700,000 of merchandise (i.e., liquor) plundered. Bottom line? Anyone who wanted to be a bootlegger needed to be very good at watching their back.

What happened to bootleggers after the repeal of Prohibition?

Franklin D. Roosevelt ratified the repeal of Prohibition on December 5, 1933, and there was much rejoicing. But what happened to all of the people who had been arrested for bootlegging?

Indiana University professor Ruth Engs says (via VinePair) that few individuals were released after Prohibition was repealed. She explains that since they had committed their activities while they were crimes, they were still held responsible for breaking the law. Engs also says that while bootleggers could petition their state governors for their freedom based on the repeal, it's unknown how many were successful.

There's another consideration, too: many bootleggers were jailed on multiple offenses that often had nothing to do with the actual liquor, like gun crimes, cross-border smuggling, or tax evasion. As a result, many bootleggers who were cooling their heels behind bars weren't nearly as excited for the end of Prohibition as much of the rest of the country.

Bootleggers had to live with hundreds of thousands of deaths

You could argue that bootleggers just wanted to make it possible for people to relax with a whiskey after a long day at work, but there was a very dark side to bootlegging — anyone who manufactured or traded homebrewed liquor needed to be okay knowing that they were killing people.

Iowa PBS explains that there were many health risks associated with drinking bootlegged alcohol, and that there were a ton of terms for the symptoms, including terrifying-sounding ailments like "swell head," "limber neck," and "Jake paralysis." The Mob Museum says that a Boston brew called Ginger Jake was found to be responsible for crippling up to 100,000 people, hence the name "Jake paralysis." How did that happen? The manufacturers added a plasticizer used to make celluloid film and explosives, known as Lindol, to their drink to hide the alcohol. But Lindol was toxic to nerve cells and caused paralysis below the waist, which was usually permanent and included impotence in men.

The U.S. government also caused thousands of deaths. Knowing that bootleggers were using industrial alcohol to make booze, federal officials ordered the poisoning of industrial alcohols manufactured in the United States. The aim was to scare people into giving up bootlegging and covert drinking, but, Slate points out, by the time Prohibition ended in 1933, the federal poisoning program had killed at least an estimated least 10,000 people and permanently damaged the health and lives of countless more.