The Most Audacious Air Raid Of WWII

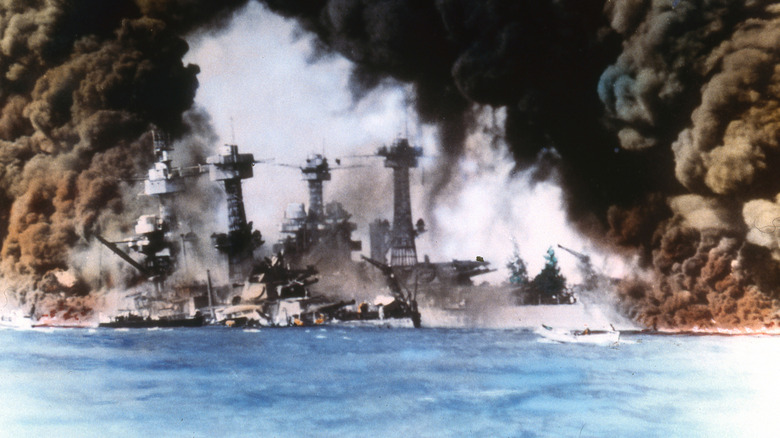

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor pulled the reluctant United States into World War II, Americans wanted to strike back. Most people realized that crushing the sprawling and well-armed Japanese Empire wouldn't be a quick project, but giving Japan a bloody nose and avenging Pearl Harbor, at least in part, was psychologically important to the budding American war effort.

An air raid on Tokyo was just the ticket, and it was doable — barely. The result of pushing aircraft (and their pilots) to their limits and taking a big risk on landing in parts of China still controlled by friendly forces, the Doolittle Raid was the first of many, many American sorties to darken Japanese skies during the remainder of the Pacific war. While the damage on the ground was limited, it proved to the governments and people of Japan and the United States that American forces could and would strike the Japanese homeland with any weapons at their disposal.

When the US entered WWII, the Japanese homeland was well insulated by its conquests

By late 1941, when Japan tried to knock American forces out of the war with the suckerpunch at Pearl Harbor, the Japanese Empire had spread far beyond the Japanese Home Islands. Japan had held Taiwan since 1895, Korea since 1910, and Manchuria since 1931. Japanese forces had expanded into large chunks of China after the renewal of open war between the two countries in 1937. And Pearl Harbor had only been part of a larger plan, with Japan attacking other American possessions as well those of France, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands at about the same time. As a bonus, they forced the previously neutral Kingdom of Thailand into an alliance. Further out into the Pacific, they nabbed Guam and Wake Island from the United States.

All this meant that the Japanese Home Islands — the part of the Japanese Empire that was actually "Japan" — was insulated from potential attack by a huge buffer zone of occupied territory. Hitting Japan and not merely a territory it controlled would require going over or through miles and miles of land or water crawling with Japanese fighters, riding high on a series of colossal successes.

But an attack on Japan was desirable to raise American morale and shake Japanese confidence

Not only was Japan doing well in late 1941 and early 1942, so were the European Axis members: The Nazi navy was savaging Allied shipping in the Atlantic with submarine warfare, and the German army was waiting out the winter in positions close to Moscow, even as other forces continued the strangling Siege of Leningrad. The London Blitz was over, but German aircraft were still harrying the cities of the United Kingdom. Hitler was doing so well in Europe he had invaded North Africa.

The Allies needed a pick-me-up, something to make victory seem at least possible, so U.S. president Franklin Roosevelt ordered his men to figure out how to bring the war to Japan, just to prove it could be done. Bombing Tokyo would cheer Allied hearts across the globe, and if successful would have the equally desired effect of denting Japan's ability to build and outfit war materiel. Bombing well-insulated Japan from such a distance would require clever planning and a fair bit of ingenuity, but the Allies were desperate for a win. FDR would give it to them.

Army Air Forces officer James Doolittle was tapped to plan and lead the raid

The man for the job was James H. Doolittle. Doolittle had been a U.S. airman in World War I, later going for a doctorate in engineering from MIT; lest this sound stuffy, he also raced aircraft and set a speed record in 1932. He'd returned to the Army Air Forces after Pearl Harbor. If anyone could figure out how to get an American plane over Japan and an American bomb onto Tokyo, it was Doolittle.

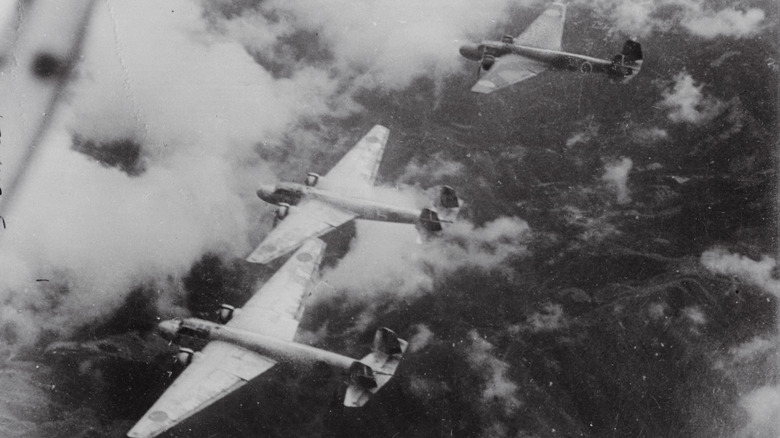

Doolittle and colleagues chose the newly operational B-25 bombers, recently successful in thwarting Japanese advances in Burma, for the job. This model would monopolize American bombing of Japan until 1944, when the capture of the Marianas Islands allowed heavier Superfortresses to participate. The particular planes that would be used were outfitted with extra fuel capacity and lightened to make them as lean and efficient as possible. Radios and guns were even removed, as every pound counted, but fake guns were added in hopes of spooking Japanese pilots.

As for the huge distances involved, Doolittle had two ideas for how to shorten them. The first was to launch the bombers from the deck of an aircraft carrier, which could approach Japan as part of an armed flotilla. The second was that the pilots ... wouldn't return. After an initial request to let them land in the Soviet port of Vladivostok was rebuffed, as the Soviets really couldn't afford to fight Japan at the moment, the pilots were instructed to overfly Japanese-controlled territory and land where they could in Free China.

Training was carried out in secrecy

Some 140 men were recruited from the 17th Bombardment Group for training and consideration for the developing Doolittle Raid. They would have a lot to learn, and not much time to do it. Keeping the raid secret was vital to its success, and few projects as big (and exciting) as the Doolittle Raid stay under wraps for long. Ultimately, they would have about three weeks at a secret site in Florida to prepare. The Doolittle pilots had to be able to fly at low altitudes with specially manufactured, inexpensive sights — the good ones were a closely guarded secret, and the brass wanted to prevent their being captured along with any planes that fell into Japanese hands. Pilots practiced on ranges painted to demarcate the tight takeoff distance available on the deck of an aircraft carrier.

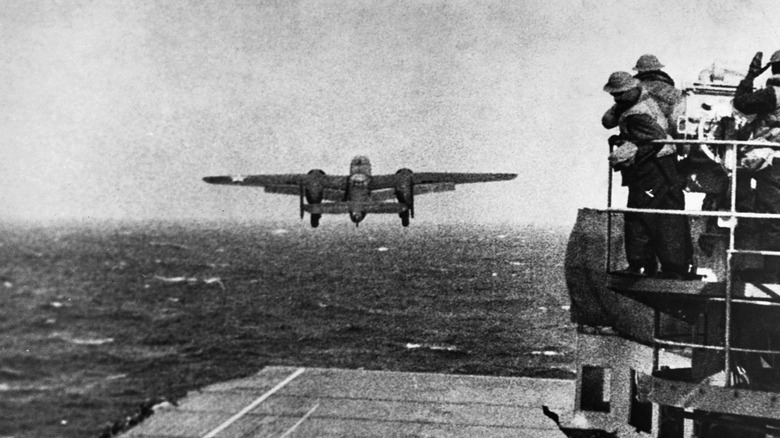

Gunners got some practice, but there wasn't time to set up an optimal firing range. Navigators had to practice flying without visual landmarks, as the Pacific Ocean is pretty same-y much of the way, and they wouldn't have access to friendly radio support. Training continued even after the aircraft carrier USS Hornet, laden with the stripped-down bombers and their crews, and its armed escorts charged out of the port at San Francisco on April 2, 1942. Gunners shot at kites, with their motion in the wind hopefully preparing them for Japanese aircraft carrying out evasive maneuvers.

Doolittle and his crew feared a Japanese patrol had rumbled them, so they had to take off early

The Japanese were surveilling U.S. radio traffic, of course, and had picked up on the possibility of a U.S. raid launched from an aircraft carrier at some point in April. The Japanese navy had built a surveillance network of fishing trawlers outfitted with radio signals in order to scan the Pacific for an American attack group, and unfortunately, one of these spotters caught sight of the USS Hornet and its escort ships on April 18, when the flotilla was about 650 miles from the Japanese mainland.

The Americans were rumbled, but at least they knew it. They launched early, limiting their options in the air but also potentially moving before the Japanese could really respond. The Japanese forces assumed the raid flotilla would try to approach Japan much more closely, about 200 miles from land, and deployed their defenses accordingly — but they were planning to fight boats, not planes already aloft, and they were unprepared for the actual threat that materialized. Meanwhile, U.S. planes from the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (no relation) pelted the ships of the Japanese warning system that had sighted the flotilla, sinking a few boats and limiting the network's efficacy in that area. The Hornet and her support ships retreated from Japanese-held waters safely, without further incident. It was all up to the pilots.

The planes did limited damage to Tokyo and other cities

The Doolittle Raiders had been instructed to spread across a wide arc to make detection more difficult and, hopefully, to make their force appear larger. Five groups of three planes each set out for Japan, with three groups aimed at Tokyo and the others with assignments in Yokohama (which hosted a shipyard), Osaka, Kobe, and Nagoya. Doolittle's plane (for a total of 16 planes in the raid) would go first, with the intention of landing incendiary bombs in central Tokyo to scare the Japanese and provide a beacon of burning buildings to help the subsequent crews navigate. They were to avoid nonmilitary targets, especially the Imperial Palace.

The raid went off as well as could be hoped. The raiders spotted only occasional vessels as they approached Japan, and they were able to strike nearly every target they had intended, setting large fires and smashing factories and armories. Japanese anti-aircraft crews spotted them and fired but weren't especially accurate and tended to shoot wide. Eighty-seven people were killed on the ground, including at least one child at an elementary school mistaken for a factory. While the damage to Japan's cities and war industry would ultimately prove not to be severe, the point had been proven. The United States could bomb Japan, and boy, was it going to.

The Doolittle Raiders then landed (or ditched or crashed) in China

The Doolittle Raiders' luck as they continued past Japan toward their planned ditch point in China was more mixed. The plan was to rendezvous if possible at the city of Quzhou, free of Japanese troops, but the raiders ran into severe storms over the sea between Japan and the Asian mainland. Most of the crews ultimately had to bail out or ditch their craft, and three men died in accidents during these maneuvers: Leland Faktor, William Dieter, and Donald Fitzmaurice. Happily, though, 13 of the 16 crews found themselves somewhere in Free China and eventually gathered in Chongqing, then the capital of the Nationalist Chinese government.

Two crews landed in occupied China, and they were taken captive by Japanese forces. All eight captives were subjected to some degree of torture. In October 1942, Dean Hallmark, William Farrow, and Harold Spatz were executed by their captors, against the rules traditionally protecting prisoners of war. Robert Meder died of an illness in captivity in 1943, and the remaining four, Robert L. Hite, Chase J. Nielsen, Jacob D. DeShazer, and George Barr, would remain in Japanese custody until the end of the war.

The last crew had the odd experience of landing in the Soviet city of Vladivostok. The Soviets and the Japanese were not yet at war, so the Soviets arrested the crew and then transferred them to custody in a location near the border with Iran, then under joint Soviet-British occupation. From there, it was easy to "accidentally" let them "escape," permitting the Soviets to do the American crew a solid without openly provoking Japan.

A furious Japan punished China

Grateful Chinese civilians had helped some of the Doolittle Raiders after they crashed, and the Nationalist government had given them refuge. For this perceived sin, Japan was willing to unleash absolutely savage reprisals, largely against civilians. Unoccupied China remained a liability for Japan, and the imperial government intended to communicate that cooperation with the United States against Japan would carry an unacceptably high price.

Japan's first move was blasting airfields in the unoccupied coastal provinces of China, hoping to keep this long stretch of coast from turning into a massive airbase from which more bombs would rain on Tokyo. (The U.S. ultimately just used Okinawa instead.) Japanese forces savaged Chinese civilian targets in an orgy of indiscriminate murder and sexual violence, a pattern they had established at the sack of Nanking in 1938. They took the city of Nancheng, some of whose residents had helped the raiders, and occupied it for a month, picking out those accused of aiding the Americans for particular torture, before burning it and leaving.

Quzhou, where the raiders intended to land, and Yushan, which had treated them to a parade, were bombed to smithereens, with over 12,000 killed in just those two cities. Japanese forces also attacked livestock and burned crops, condemning survivors to a hungry grief. As a crowning grotesquerie, Japan's germ warfare unit laced the reprisal area with pathogens like typhoid and cholera, ensuring another wave of death.

Doolittle expected punishment but was rewarded

Poor James Doolittle thought the raid had, effectively, failed, since they'd been spotted and had to take off early and then had been scattered in China with some loss of life. He apparently expected to receive a court martial when he returned to the United States, but few people have misread their situation as completely as Doolittle. On his return, his military rank was bumped up two entire levels, making him a brigadier general. In addition, he was granted the Congressional Medal of Honor for "conspicuous leadership above the call of duty, involving personal valor and intrepidity at an extreme hazard to life." (The formal commendation calls it a "highly destructive" raid, which is pushing it, but he did hit Tokyo, and the U.S. did win the war.) Doolittle was also played by top-shelf star Spencer Tracy in the 1944 war film "Thirty Seconds over Tokyo."

Doolittle remained in active service during the war, serving again in the Pacific and in Europe, as well as leading the U.S. 12th Air Force in North Africa and the Mediterranean front. After his retirement, he was made a four-star general and was also granted the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He moved back into the civilian sector after the war and died in 1993, outliving, to his probable pleasure, Emperor Hirohito, whose palace Doolittle had spared in 1942.

The raid indirectly helped the Allied cause

The material damage from the Doolittle Raid wasn't much — it didn't even take Japan long to repair the hole in their early warning fleet the raiders' naval support had cut — but the psychological effects and the subsequent choices Japanese war planners made proved to be advantageous for the Americans. Jittery at just how close the Americans had gotten, the Japanese brass elected to keep four army fighter groups in the Home Islands just in case, and of course, men kept back to defend Japan against a what-if that never came weren't available to support operations on other fronts of the war.

Japan also decided that their defensive perimeter (which had failed) needed to be even bigger, despite the fact that they were stretched thin in the Pacific as it was. The Japanese navy was able to bully the army into agreeing to its plan to seize the miniscule but strategically located islands of Midway Atoll, an American possession, allowing them to menace Hawaii and maybe isolate Australia.

The resulting Battle of Midway was an absolute fiasco for Japan. Despite early successes, they lost four aircraft carriers, a battleship, and hundreds of planes, along with 3,000 men. Japanese survivors scooped up by American craft spilled important tactical information. Japan was unable to move against several island groups in the South Pacific and never really regained the upper hand in the war.

After the war, one raider returned to Japan as a missionary

One of the POWs held in harsh conditions by Japan would return after the war with a message for his former captors: the Gospel. Jacob DeShazer (front left) had been held from his capture until the end of the war, with nearly three full years in solitary confinement. He managed to get access to a Bible during his confinement, studying especially the Acts of the Apostles and the letters of St. Paul. DeShazer was liberated a few days after Japan's surrender in August 1945, and after a period of recovery in the hospital went on to train as a missionary.

Wife and son in tow, DeShazer arrived in Japan in 1949 and over the coming decades established a network of churches around the country. Among his most notable converts was Mitsuo Fuchida, the officer who had planned the Pearl Harbor raid, who was led by DeShazer's writings to the Bible and then, ultimately, Christianity. After a career evangelizing in Japan, DeShazer retired to his native Oregon and died there at the age of 95, survived by a bumper crop of children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren.