The Daring WWII POW Raid On Los Baños

In 1939, World War II broke out in Europe, and in the coming months and years, countries across the globe were drawn into the conflict. Before its end in 1945, the bloodshed produced some of the most jaw-dropping stories in human history that sound fake. From European politicians' attempts to appease Adolf Hitler, the expansionist leader of Nazi Germany, to the viciousness of the attack on Pearl Harbor, to the barbarity of the blitz and Dresden firebombing, to the horrors of the Holocaust, WWII showed us most of the worst of human nature.

But among the stories handed down to us from this period are many that show the great bravery and cunning of the Allied forces as they fought to ensure ongoing peace and freedom for the world. Future President John F. Kennedy became a war hero for his actions in the U.S. Navy, while pilots were lauded for their daring, such as the British Air Force during their famous "Dambusters" mission. And over in the Philippines, there was the raid on Los Baños, a Japanese prisoner of war camp that saw U.S. forces conduct one of the most precise and successful missions of the entire conflict. Today, the daring raid on Los Baños, which potentially saved thousands of lives, is held up as an example of supreme military competence. Here's the story.

Reports of brutality at Los Baños POW camp

Internment of Westerners in the Philippines, which was then part of the United States, began shortly after the Japanese invasion in 1941. The occupiers were looking to limit potential resistance among the population, and Los Baños was one of several prisoner of war camps operated by the Japanese in the Philippines in the final year of World War II. Opened in 1943 and located south of Manila, by February 1945, Los Baños housed over 2,147 Allied prisoners.

The POW camps in the Philippines were considered harsh to begin with. But as the years rolled on and the Japanese struggled to maintain control of the occupied territory, conditions in the camps became unbearable. Abuse of prisoners was commonplace, as was sickness and malnutrition. Hygiene standards disappeared, food rations began to be cut, and aid was withdrawn by their captors.

Sister Eleanor Francis Andrews, a Maryknoll Mission nun who had been interned in the camp since December 1941, wrote in her diary on February 21, 1945: "Apparently zero hour has approached. No more food in the camp. Tonight is our last meal unless something happens. At a Committee meeting the Japanese told them that there was starvation everywhere, U.S., Philippines, even in the U.S. Army. The Japanese around this camp are certainly well fed." Little did she know that, finally, help was imminent.

The Allies decided to intervene

The suffering of the POWs held by the Japanese in camps throughout the Philippines had increased after the Allies launched their counterattack in the territory. And as it looked increasingly likely that Japan was to cede control of the occupied territory, the Allied command received some incredibly disturbing intelligence about the potential fate of those kept in the camps. According to information received by Filipino guerillas working with the U.S. in December 1944, Japanese forces had ruthlessly executed 139 American prisoners after forcing them to endure a period of hard labor on the island of Palawan. Not only that, but there was reason to believe that the Japanese captors looked likely to massacre the remaining prisoners to prevent them from falling into the hands of the advancing liberators.

In response, U.S. General MacArthur instructed Lt. Gen. Robert Eichelberger to intervene, and Eichelberger then handed responsibility of liberating Allied POWs in the Philippines to the 11th Airborne Division, a crack team of paratroopers of the U.S. Army. In the first weeks of 1945, the Allies began successfully liberating POWs in the Philippines. Even when liberating camp populations of just a few hundred, they encountered resistance. But Los Baños, with more than 2,000 held, remained a large-scale and important operation that, were it to fail, could lead to a catastrophic loss of life.

The importance of guerilla intelligence

To characterize the mission to liberate Los Baños as solely the work of the U.S. Army is to overlook the huge importance of Filipinos on the ground. Particularly Filipino guerillas, who worked closely with the Army to mount an effective resistance against the Japanese invaders. Los Baños was located deep in territory controlled by Japanese forces, meaning it would have been a difficult task for U.S. troops to gain intelligence about the situation on the ground single-handedly.

But the Filipino guerillas — 300 of whom are reported to have assisted in liberating Los Baños either through intelligence or the raid itself — knew the landscape around the camp intimately. As well as giving the 11th Airborne Division details of the camp itself, they also served as scouts and guides for group troops and as combatants themselves. It was the guerrillas who first assisted in helping bring information as to the dire situation in Los Baños to the U.S. high command.

The Philippines had been part of the U.S. since December 1898, when Spain ceded the country to America as part of the Treaty of Paris. The handover was followed by a brutal three-year conflict as American occupiers fought to control the Indigenous population, and eventually, in 1935, it became an autonomous commonwealth. On July 4, 1946 (a day the Philippines still celebrates), just a year after the successful liberation of Philippine POW camps and defense of the territory against Japan, the Philippines was finally granted its independence, once again becoming a sovereign nation.

An elaborate raid structure

Raiding a heavily armed prisoner-of-war camp in the middle of the swampy Philippines jungle isn't something that can be done with just brute force. As the Allies knew, thanks to the intelligence received from Filipino guerillas and escapees of the camp, it would take a sophisticated and daring multi-part operation to liberate all the prisoners and take them to safety without the risk of loss of life. The 11th Airborne Division gave the task of liberating Los Baños to the 188th Glider Regiment, led by Colonel Robert Soule.

It was planned that a ground force raiding party would be the first force to seek out Los Baños and engage with the camp. Meanwhile, nine aircraft were to be used to provide air cover and drop paratroopers into the camp, while 50 amphibious tractors, aka amtracs, were to arrive on the scene when the prisoners were liberated and take them back to safety on U.S. territory. Suffice to say, the element of surprise was vital for minimizing the chance of resistance and the arrival of Japanese reinforcements. It was a bold plan.

The raiding party prepares to attack

The raiding party consisted of 32 American ground troops, who were to be deployed in the area along with 80 Filipino guerillas. The party was mobilized with the use of canoes, which they used to arrive on the island of Luzon, where Los Baños is located. From here, they would get into position to attack the Los Baños POW camp.

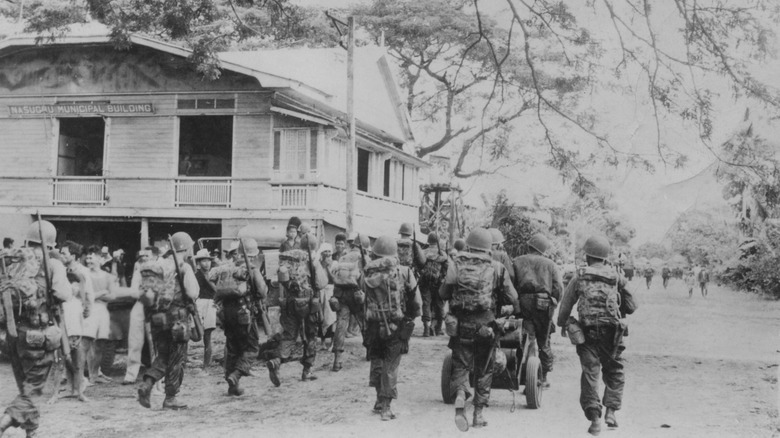

The camp was located 50 miles behind enemy lines, and getting into position took the raiding party several days of difficult travel after they arrived on the island. They moved mainly at night, hiding from Japanese troops who, if they discovered the Allies, would have understood that an incursion was in the works and signalled for reinforcements in the area, scuppering the vital raid. After reaching their agreed spot near the camp, the raiding party went into hiding until the time came to attack. In the early hours of the morning on February 23, 1945, the raiding party began its move on Los Baños prisoner-of-war camp, unleashing fire against the camp's armed guards.

The signal comes from the raiding party

The American and Filipino raiding party spent days marching toward the Los Baños prisoner-of-war camp through swamps, jungles, and paddy fields, evading detection by Japanese soldiers as it went. And it wasn't simply tasked with making the first strike against the guards protecting the camp — the group was also vital in helping the other parties involved. Particularly, the planes full of paratroopers that were due to appear above Los Baños after the raiding party's first engagement, as well as the 50 amtracs that would head to the camp to find Los Baños once the raid was underway.

The party threw smoke grenades to release huge plumes of visible smoke that the Allies in the air and on the water could use to navigate their way directly to Los Baños. Some of the grenades marked the camp itself, where paratroopers would land. Others were used to signal the landing beaches on which the amtracs were to climb onto the island.

Storming the camp

As the raiding party began its attack and the smoke signals billowed in the air, the paratroopers in the air and another group in the first amtracs to arrive on land began to mobilize. As prisoners at Los Baños recalled later, the people who had endured the hardships of the camp for several years thought the troops landing by parachutes were angels descending from the sky. At the beaches where the amtracs were arriving, 2.5 miles away, paratroopers set up a defensive perimeter to counter Japanese interference, turning two howitzer machine guns on a nearby militarized lookout spot.

The attack began just before 7 a.m., while many of the off-duty guards were exercising and prisoners were eating their breakfast. As the firing started, prisoners fled back to their barracks. "With bullets flying just over my head through the grass mat walls, I lay on the floor under my bunk, eating my breakfast," said Robert A. Wheeler, who was 12 years old at the time of the raid (via Warfare History Network).

The paratroopers dropping from the sky soon assembled just a few hundred yards from the perimeter of the camp, and from there their assault began. The fighting was concluded in roughly 20 minutes. Guards at the camp were either killed or forced to flee after being caught unaware by the Allied surprise attack.

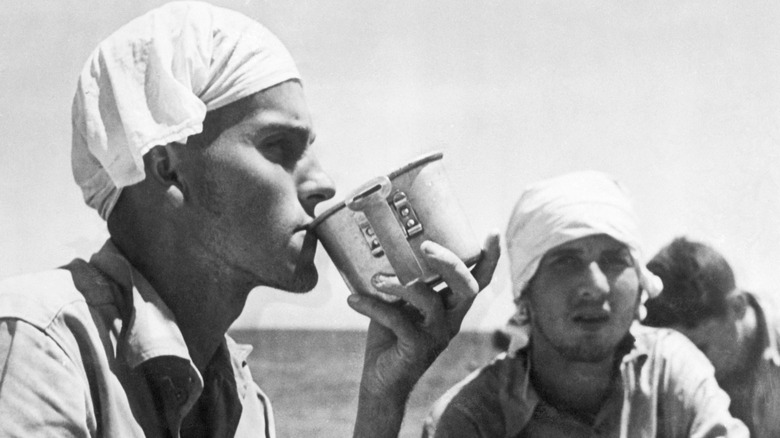

Many prisoners required immediate medical attention

Once the Los Baños POW camp was cleared of guards — Filipino guerillas were effectively positioned to hold off any chance of Japanese reinforcements reaching the camp while the raid was taking place — the attention of the Allies immediately turned to the plight of the now-liberated inmates. Those who had been held at Los Baños were in shocking condition when the Allies found them, especially as a result of malnutrition. In the final week of their captivity, prisoners were being forced to live on a ration of just 2.5 ounces of unhusked rice per day.

Many of those who were interned in the camp had in the early days bartered with their Japanese captors, giving watches and other expensive objects in exchange for food items. But for most prisoners who had lived there for multiple years, those days were long gone. Many had survived eating wild animals, including cats, dogs, and rats, as well as insects and weeds. They had been eaten alive by clouds of mosquitoes in the barracks night after night, with no modern forms of prevention or relief. In January, the Japanese guards abandoned the camp, believing a U.S. invasion was imminent, and prisoners enjoyed a short period of freedom when they were able to eat well with local Filipinos, but it lasted a matter of days.

As such, many of those who were liberated from the camp were too weak to walk and were assisted to the amtracs. Others who were stronger walked alongside the vehicles on the way to the beach, carrying what possessions they still had. Once the amtracs made it to the water — a journey that included another skirmish with Japanese soldiers — the remaining internees and the paratroopers entered the vehicles.

There were minimal Allied casualties

The amtracs carrying the returning paratroopers and the rescued former Los Baños inmates were tormented by Japanese artillery and mortars as they crossed the water, but there were no direct hits. Eventually, they made it safely to Mamatid, where ambulances and medical staff were on hand to treat the inmates. Despite the daring nature of the surprise Allied raid at Los Baños POW camp and the prevalence of Japanese soldiers in the area in the territory they controlled, the mission was completed with an astonishingly small number of casualties when compared to the lives that were undoubtedly saved that day. One added aspect of the attack was the inclusion of a diversionary attack that was intended to draw the attention of potential Japanese reinforcements, meaning that the camp was liberated with minimal resistance.

Two American troops were killed in action, and three were injured. Only a single injury actually occurred in the raid of the camp — the other casualties were the result of diversionary combat. Two Filipino guerrillas were also killed in the mission. On the other hand, the Japanese suffered 243 fatalities.

The aftermath for those rescued

After the liberation, many of the POWs faced a long spell of recuperation for the many ailments that developed in the camp. Just as with the raid itself, the support facilities required to ensure the detainees' eventual evacuation from Luzon were meticulously planned. Those freed were taken to New Bilibad, with its prison serving as a makeshift camp for them as they recovered their strength after weeks of near starvation. The prison hospital and other facilities on-site were especially cleaned and prepared for their arrival, and on the first night, food was served from 4:00 p.m. until after midnight.

The former prisoners were also treated to recreation, which included a record player and movie screenings. The prison's chapel came to serve as the mess hall, large enough to seat 750 diners, and 107 people were treated by medical staff for conditions like malnutrition and beriberi disease. This number included three women who were given medical support while pregnant. By March 8, the majority of those rescued had been transported from the island.

The legacy of Los Baños

The raid on Los Baños is considered one of the Allies' most successful WWII operations, with more than 2,000 Allied lives saved from massacre just as the war was winding down. It continues to be celebrated by military enthusiasts today, with the Warfare History Network's Gene Eric Salecker stating that it is "remembered as a textbook operation" that was "carried out in a virtually flawless manner." It is often held as a counterpoint to other U.S. attempts to liberate prisoners of war that have ended in disaster, such as the Son Tay raid, in which faulty intelligence led to a mission at a camp where the prisoners had already been removed. Similarly, the Mayaguez incident — the final battle of the Vietnam War that took place at sea — resulted in significant U.S. casualties due to faulty information and poor planning and execution.

Tragically, the success of the Los Baños raid and the assumed collaboration of Filipino locals in assisting the Allies to free those held in the camp saw horrifying repercussions for those living nearby. With the Japanese occupiers convinced that local people had assisted in the Los Bańos mission, around 1,500 people were executed. It was a horrifying consequence for a population that had already seen their lives torn apart by the Japanese invasion, which had already seen other atrocities like the Bataan Death March.