How The U.S. Lost 6 Nuclear Weapons And Other Broken Arrow Tales

If you really want to sum up a particular period in global history in a way that genuinely oversimplifies things, it's clear that the Cold War was really, really tense. From the late 1940s until the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991, two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, were constantly at odds and preparing for the other side to instigate war. And this wouldn't be a conventional war, either. Instead of ground-based offensives or airborne dogfights, if the Cold War turned hot, it would almost certainly involve the detonation of some of the world's increasingly large arsenal of nuclear weapons.

That left people seemingly everywhere on high alert, with militaries on both sides arming submarines, planes, rockets, and more with nuclear warheads. The accidental launch of one was a very real possibility — everyone thank Stanislav Petrov for saving us from nuclear armageddon — while the sort of whoopsies that would be easily dismissed in an office job sometimes led to the loss of nuclear bombs even when hostilities weren't ongoing.

These last circumstances have led to what are often known as "Broken Arrow" incidents. This bit of military jargon broadly refers to accidents involving nuclear weapons, which, as of yet, have not involved any actual thermonuclear detonations. However, they have resulted in the disappearance of six known bombs, as well as the fragmentation of others and the occasional blast of conventional explosives that has likely disturbed quite a few fish and basically leveled one house in South Carolina.

The first weapon was lost in the early years of the Cold War

In February 1950, a B-36 bomber was on a practice run that would have taken it from Alaska to Texas. As part of this training exercise, Strategic Air Command had borrowed a nuclear weapon from the Atomic Energy Commission to place on the plane, though the Mark IV bomb it secured had no plutonium trigger. Its uranium and conventional explosives (necessary to keep a core together and ensure it reached criticality) could still cause plenty of damage, though it would not be a city-leveling event.

As the B-36 flew through the chilly air, ice began to accumulate on the craft, increasing weight and putting serious strain on its engines, to the point where three of its six engines caught fire and were shut down. Then, the bomber began losing altitude. Not wanting the Mark IV bomb to get into the wrong hands, the crew jettisoned it above the Pacific. Crew who bailed out of the plane in the cold and dark later said they saw it detonate.

The plane's autopilot was set to send it into the ocean, but instead it turned and crashed into the mountains of British Columbia. Of the 17 crewmembers, 12 survived. Conspiracies claim that the weaponeer, Captain Theodore Schreier, stayed aboard and attempted to bring the plane back to Alaska, meaning that the bomb might have landed on Canadian soil. However, multiple investigations of the crash site on Mount Kologet have found no evidence of the weapon.

A jet carrying 2 potential weapons was lost without a trace

In March 1956, a B-47E Stratojet took off from MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa, Florida. The intent was for this plane to make a nonstop flight to the Ben Guerir Air Base in Morocco, though this long haul would be assisted by two mid-air refueling maneuvers. The first such refueling took place as expected and the B-47, with its crew of three, continued on. Yet, the second meetup with an airborne tanker plane didn't go nearly as well. The last anyone knew, the B-47 was preparing for its second refueling by descending through a thick cloud layer to 14,000 feet, at a point above the Mediterranean Sea. Visibility wasn't terribly good, but, with the base of the clouds at around 14,500 feet, the jet and its refueling tanker should have been able to see one another. Yet, the B-47 never appeared.

Even more worrisome: the fact that the B-47 was carrying two capsules of nuclear weapons material, though these were in carrying cases and not necessarily assembled into bombs. Despite a large search and reports that the craft may have gone down near an Algerian village on the coast, no trace of the plane or its three-person crew have ever been found. To the best of anyone's very limited knowledge, the two cases of nuclear material went down with the plane and sunk with the rest of the craft's debris.

A 1958 mid-air collision led to another Broken Arrow incident

In February 1958, a B-47 bomber was preparing to set out on a training mission that would prepare them for an attack on the Soviet Union — only, using a Virginia town as a stand-in for Moscow. But while geography demanded a substitute Soviet capital, the plane was carrying a real Mark 15 nuclear weapon, allowing the crew to see what it was like hauling a 7,600-pound bomb for hours upon hours of flying time. All seemed well until the last leg of the trip, when the two B-47s in the mission came across another training flight. In the confusion, the B-47 carrying the bomb was struck and, though still airborne, needed to make an emergency landing, and fast. That necessitated dropping its heavy cargo, and so the 3.8-ton bomb went plummeting 30,000 feet into the waters near Tybee Island, just east of Savannah, Georgia.

Thankfully, the bomb did not detonate, but its payload of 400 pounds of explosives in addition to an unknown amount of nuclear material (some allege that the training bomb actually contained its plutonium detonator, though that's unconfirmed) meant the military very much wanted to recover it. The search effort went on for over two months, but nothing was recovered. What remains of America's Tybee Island Bomb is, as far as anyone can tell, still buried somewhere in the sediment just off the Georgia coast.

Parts of a nuclear weapon are still embedded in North Carolina

In the first month of 1961, a B-52 bomber was in the skies above Goldsboro, North Carolina. It was on an airborne alert mission meant to keep a near-continuous slate of nuclear-armed planes in the skies, on the lookout for Soviet aggression. It would have been a precursor to or early participant in "Operation Chrome Dome," a U.S. Air Force initiative that was active from 1961 to 1968. Crews would expect to take on long 24-hour missions that included mid-air refueling stops.

However, wing trouble quickly led to catastrophic structural failure and the release of the plane's payload of two nuclear weapons. Both bombs had emergency parachutes, but only one deployed and carried its bomb safely down. The other slammed into the ground and broke apart, though it did not detonate.

The Air Force had a difficult time finding all its pieces and ultimately had to admit that parts of it — including portions containing uranium — would just have to stay in North Carolina. It purchased land rights for the area and disallowed any unauthorized digging. Official documents claim there is no radiation hazard in the area, though that hasn't always put people at ease. As Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara noted in a 1963 meeting, this and another Broken Arrow incident in Texas were occasions "where, by the slightest margin of chance, literally the failure of two wires to cross, a nuclear explosion was averted."

A nuclear weapon slipped off an aircraft carrier

In the last few weeks of 1965, an A-4E Skyhawk slipped into the ocean off the USS Ticonderoga, an aircraft carrier stationed near Japan in the Philippine Sea. Inside were both the pilot, Lt. (junior grade) Douglas Webster, and a B43 nuclear bomb with a one-megaton yield, then the maximum yield available for a weapon of that type. It was supposed to be part of a training exercise in which crewmembers loaded the bomb, moved the plane to the flight deck, and then staged it as if the jet were about to take off. According to an eyewitness account by Chief Petty Officer Delbert Mitchell in a 2019 volume of Naval History, he and other members of the crew were anxious to get it all over with.

Then, the plane began to roll. Webster apparently missed signals to apply the brakes and, despite the actions of crewmembers who attempted to stop the craft with wheel chocks, the plane tipped over the edge and went into the ocean. Though Mitchell and others ran to the edge of the deck, they could only watch helplessly as the Skyhawk sank. Recovery efforts only found Mitchell's helmet. With the airplane, pilot, and a thermonuclear weapon now presumably at the bottom of the ocean, the U.S. decided to keep largely quiet. It didn't actually disclose this incident to Japan until 1989, even though it happened roughly 200 miles northeast of its southern islands of Okinawa.

1 Broken Arrow incident remains mysterious

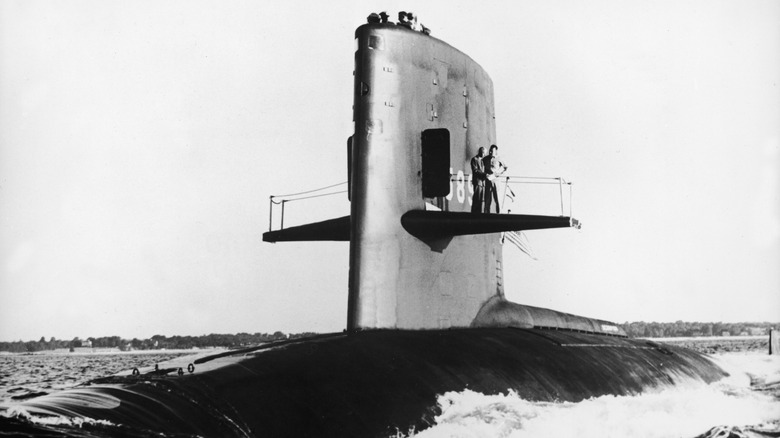

Going by Department of Defense records, we know only that something went missing "At Sea, Atlantic" in the spring of 1968. Otherwise, it said, "Details remain classified." We can reasonably conclude that a U.S. craft carrying nuclear weapons was lost somewhere in the Atlantic at the height of the Cold War. Many have also noticed that the place, time, and weapons capability line up with the disappearance of the U.S.S. Scorpion, a nuclear-powered submarine that went missing in May 1968. Ninety-nine crew and at least one nuclear weapon went down with the sub, according to inside sources (though official government info hasn't been quite so forthcoming).

However, the story didn't end in spring. In October of that year, as part of a larger search that also led to the discovery of the Titanic wreck, a U.S. Navy research vessel located parts of the lost submarine about 10,000 feet deep in the mid-Atlantic, some 400 miles southwest of the Azores. The site has been surveyed multiple times since, though it's unclear if any nuclear material has been recovered from the wreckage.

As for what sank the Scorpion, most sources agree that some sort of mechanical failure took it down, and not a Soviet attack as feared — though perhaps all the secrecy had to do with worries that some nosy Russian vessel would try to recover U.S. military secrets or even a thermonuclear weapon from the grave of the Scorpion.

A 1958 incident destroyed a house

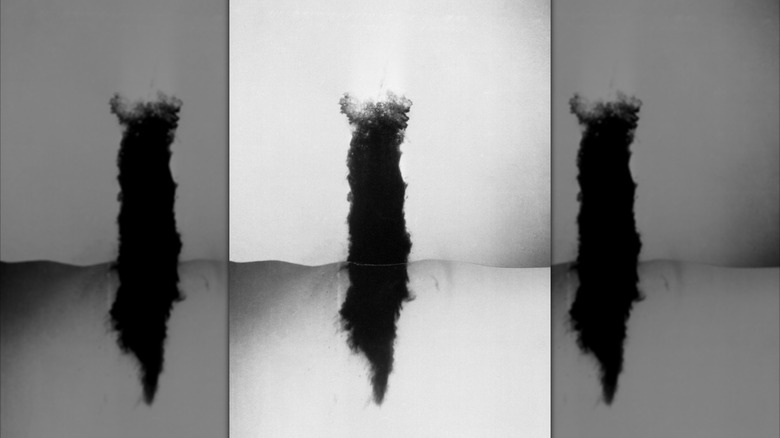

Even when a bomb didn't contain a button of pure plutonium as a trigger, conventional explosives inside a Broken Arrow could still do serious damage. That was dramatically demonstrated in March 1958, when a B-47E Stratojet flying over Florence, South Carolina accidentally dropped its nuclear weapon at 15,000 feet. It happened due to a combination of faulty mechanisms and crew error when navigator Bruce Kulka accidentally struck an emergency release pin when checking the bomb. The bomb was unarmed, but nevertheless represented serious danger as it plummeted down. Luckily, it landed in Mars Bluff, a rural area with few people; unluckily, it impacted alarmingly close to the house of Walter Gregg and his family.

Somehow, everyone survived, but many were knocked down by the tremendous force of the bomb's detonation. Some were injured, while the family home and other buildings nearby were ruined and the garden became a crater over 20 feet deep and 50-feet across. Ella Davis Hudson was just 9 and playing with her Gregg cousins; she doesn't recall the blast, but does vividly remember the cut she received just above her eye, as well as a frantic trip to the hospital and concerned medical staff waving a Geiger counter around her. Her cousin, Helen Gregg Holladay, remembered that military planes would routinely fly over afterward to measure radiation. When Walter Gregg sued the government, he was given a pittance of $36,000 — not enough to rebuild. "My daddy resented it all his life," Holladay told The Post and Courier.

A plane crash left parts of Greenland irradiated

Given that Greenland is plenty cold (though maybe not the absolute coldest place you can live), Thule Air Base was never going to be an easy place after the U.S. military took over the site in 1951. But it was an important location, allowing planes to stop over on long-haul missions and hosting a missile detection system. Even now, the operation — renamed Pituffik Space Base in 2023 — is still operated by the U.S. military. In January 1968, a B-52 on an airborne alert mission experienced a fire within the crew cabin that quickly grew out of control. When the craft began to approach Thule Air Base, the crew bailed out; six survived, but a seventh crewmember was fatally injured. The unmanned plane crashed into the ice sheet with four nuclear weapons aboard.

According to official accounts, the weapons' conventional explosives detonated and added to a massive debris field. However, the nuclear materials were not compromised and a 2001 report indicated that radiation exposure at the Thule Air Base was within reasonable standards. Yet some have since grown doubtful that the cleanup went perfectly. A BBC evaluation of government documents suggests that only three weapons were recovered, and that the fourth weapon — or at least parts of it — may have remained embedded in the ice. If this is true, however, officials may have concluded that the difficulty of retrieving any remaining bomb bits greatly lessened the security risk of leaving it in place.

One heroic pilot kept a 1961 incident from being much worse

One Broken Arrow incident could have been much worse if it weren't for the courageous actions of one pilot. It happened in 1961, when a B-52F Stratofortress carrying two nuclear weapons was flying another airborne alert mission. These two bombs were not quite like those involved in earlier Broken Arrow accidents, which often were missing the plutonium core necessary to enact full-scale destruction. Rather, each 6,600-pound bomb contained a composite core that was fully sealed.

That was considered acceptable ... until this particular B-52 began suffering from all sorts of problems early into its planned 24-hour flight, including a malfunctioning heating system and overheating of the electronics, forcing the crew to depressurize the cockpit. This ultimately led to failing instruments and crew symptoms linked to depressurization and dehydration. Yet it was directed to keep flying anyway.

Then, 22 hours in, waiting on a mid-air refueling tanker, the engines ran out of fuel and the B-52 finally began to fail. Most of the crew bailed out at 10,000 feet, but commander Major Raymond Clay stayed aboard to guide the plane away from populated areas, only parachuting out at a rather terrifying 4,000 feet. All crew survived, but the plane crashed into a remote California ranch and scattered debris — including parts of its thermonuclear bombs — across 20 acres. Thankfully, recovery teams found that the bombs, though damaged, had not detonated and all radioactive material was contained.

Spain was accidentally bombed in 1966

It's never good when one country bombs another, even if it's an accident. Thankfully, the Palomares incident didn't become an international blowup, though it did put a rural village in southern Spain in danger back in 1966. It began when a U.S. B-52 was on yet another airborne alert mission that took it over Europe. When the bomber began to approach a refueling plane, the pilot had difficulty controlling the craft's speed and collided into the other aircraft, killing the four crewmembers on board the tanker. On the B-52, four survived, though three others died. The plane, now on fire, broke up over the village of Palomares, leaving people below to deal with the charred debris ... and the four thermonuclear weapons that had been aboard.

Luckily, no one on the ground was injured. Indeed, Spanish villagers soon set to work retrieving human remains and rescuing survivors (fishermen picked up the three crew who landed in the nearby Mediterranean). U.S. Air Force personnel soon arrived and began collecting the debris and thousands of tons of contaminated topsoil, as well as marking off irradiated areas and trying to manage one of the worst toxic spills in history.

After a week, however, they had only found three bombs. At this point, the U.S. Navy joined the search, tipped off by fishermen who believed they had seen another crewmember sinking into the water. They surmised that this was actually the fourth bomb. After months of searching, a submersible finally located the weapon and it was winched up nearly 3,000 feet and disarmed.

Damascus, Arkansas had an alarmingly close call in 1980

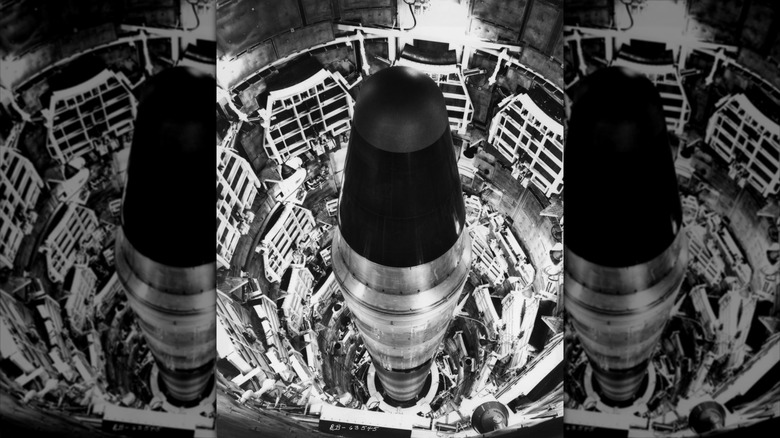

Even an innocent wrench can quickly become ominous when a thermonuclear warhead is involved. The warhead in question was in a missile sitting in the Titan II Launch Complex 374-7 near Damascus, Arkansas. The Titan II clocked in at just over 100 feet tall and about 330,000 pounds, with enough fuel to carry a nine-megaton weapon over 9,000 miles. Titan II missiles were in service for over 20 years, but their components could cause trouble, as when a 1978 chemical leak at the Damascus complex necessitated an evacuation.

The 1980 incident began when a maintenance technician working on the missile dropped an eight-pound wrench. It fell approximately 80 feet and struck one of the Titan II's fuel tanks. With fuel now leaking, the area was again evacuated. Official worried that a spark at the wrong time could ignite the fuel vapors and lead to the detonation of the missile's W-53 nuclear warhead. Teams were sent in to measure the fuel concentration in the silo.

A few hours after the initial accident, two airmen were doing just that when the missile suddenly exploded. One Sergeant Jeff K. Kennedy was thrown 150 feet away and suffered a broken leg. The other, Senior Airman David Livingston, was fatally injured — the only fatality that day. The warhead flew about 100 feet but remained largely intact and contained all its radioactive material. After a cleanup operation over a 400-acre radius, the Air Force filled in the silo with soil and rubble.