What It Was Like To Be Filthy Rich 100 Years Ago

In the 1920s, the Western world experienced an era of economic prosperity and socio-cultural shift. While the so-called "Roaring Twenties" were felt in many parts of the West, they were especially evident in — and most commonly associated with — the United States. The way the Roaring Twenties has been represented in popular culture, particularly in prominent literary works such as "The Great Gatsby," has created a nigh-indelible image of liveliness, materialism, and excess during this time of significant industrial and technological advancement. Being bookended by the First World War and the Great Depression only served to highlight the optimism in this era. The U.S.'s gross national product was on the rise, unemployment was at an all-time low, and entertainment and media experienced massive transformations.

Still, despite the fact that we've come to associate the decade with grandeur and splendor, life wasn't exactly a cakewalk for everyone. For instance, there were a lot of creepy things that were considered normal 100 years ago — although one could argue that streets strewn with animal waste, pseudoscientific medical beliefs, and racial and religious prejudices are systemic ills that never really left our society. Nevertheless, for the wealthy and affluent — the "filthy rich" — this period of plenty was, well, quite plentiful, with life offering many decadent delights and costly conveniences. A century ago, this was what it was like to be part of the Western world's 1%: the good, the bad, and the ugly.

What did it mean to be filthy rich a century ago?

To better understand how the filthy rich lived in the 1920s, it's important to define exactly what being "filthy rich" meant back then. To be truly wealthy in the Roaring Twenties was to command exceptional income streams from various industries and niches. In the expanding economy of the time, the rich got richer, and elite fortunes were concentrated among business owners and financiers. All of this happened even as a large share of households remained at or below subsistence levels. Some of the most well-known figures from the era include leading industrialists like automobile pioneer Henry Ford and bankers like J.P. Morgan. (By the way, these were the most popular jobs 100 years ago.)

The gap between the filthy rich and the poor was evident: By 1928, the top 1% of U.S. families received nearly a quarter of all pretax income, while the bottom 90% received only a little over half. Around that time, over 40% of Americans lived on less than $1,500 a year (which would be a little over $27,000 in today's money).

It's true that more American families owned cars and radios by the end of the 1920s. Yet an honest look at the decade reveals something contrary to what contemporary ideas about the Roaring Twenties might suggest. Notably, the true hallmark of this period was the disproportionate share of national income accruing to the very top, not a general rise in living standards for lower-income groups.

The concept of the 'billionaire' was new in the 1920s

As of 2025, just over 57 million people across the world can be considered millionaires, which is less than 2% of the global population. Among them, nearly 26 million are in the United States. And while it's hard to pinpoint exactly how many people were part of the global millionaire club in the Roaring Twenties (experts estimate that there were at least 319 millionaires in Britain in 1928 or 1929), we do know who the earliest recognized American billionaires were — a designation that was novel at the time.

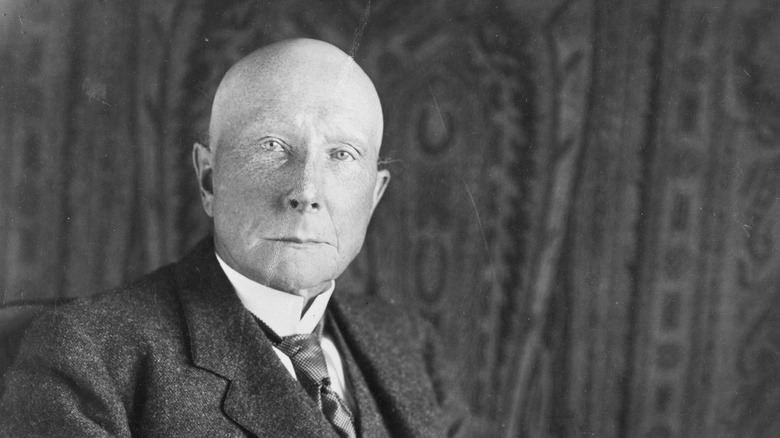

Many people point to John D. Rockefeller as the U.S.'s first billionaire. His Standard Oil Company-derived stock prices were reported to have crossed $1 billion on September 29, 1916. Adjusted for inflation, that equates to roughly $30.6 billion today. By the end of Rockefeller's life in 1937, his net worth reportedly reached around $1.4 billion, a figure equal to about 1.5% of the U.S. GDP that year. Some historians have contested this, though, with Rockefeller biographer Ron Chernow saying that the oil tycoon's fortune had actually reached its apex — about $100 million short of a billion — three years earlier.

Other experts have pointed to Henry Ford as the first true holder of the title of "Richest Man in America" during the Roaring Twenties. In 1927, the New York Times even called Ford "the first billionaire in history." Regardless, there's no doubt that both Rockefeller and Ford were among the richest men in the world during the 1920s.

Where the filthy rich lived in the Roaring Twenties

In the 1920s, many high-income families lived in large urban townhouses or purpose-built mansions in affluent corridors and resort districts, often maintaining multiple residences to avoid the scorching summer heat. Outside Manhattan, Long Island's North Shore — aka the "Gold Coast" — concentrated country houses for financiers and industrialists. OHEKA Castle, the estate of German-American investment banker Otto Hermann Kahn, was built across 109,000 square feet of land, with 127 rooms. It reportedly required extensive staff, typical of the scale of country properties used as seasonal residences near New York City.

Meanwhile, on New York's Park Avenue, railroad and mining magnate Arthur Curtiss James and his wife lived in a mansion that, in 1914, reportedly cost about $1,000,000 (about $31,500,000 in 2025 money) to build. James also maintained a Newport, Rhode Island estate called Beacon Hill, which features the Blue Gardens, a 10-acre garden that remains a present-day tourist attraction. Also on Rhode Island is Miramar, a luxurious property featuring a neoclassical French aesthetic that was commissioned as a vacation home and has been owned by a number of wealthy people throughout the decades.

In oil-producing states, elite neighborhoods also formed around industry fortunes. One example is Westover Hills in Fort Worth, Texas, which developed as a high-income enclave when the oil executives of the 1920s had their estates built there. To this day, it is considered one of the state's wealthiest suburbs.

What the filthy rich ate and drank in the 1920s

It should come as no surprise that during the 1920s, the wealthy enjoyed fine dining from expensive establishments. In New York, the prestigious Waldorf-Astoria hotel functioned as a flagship site for elite dining, with top-caliber culinary experts preparing luxurious meals for its clientele. For the filthy rich, traveling in style also meant dining in style. On the White Star Line's RMS Olympic, the Restaurant was a first-class à la carte affair that catered exclusively to top-fare passengers. The menus featured haute cuisine such as suprême de turbot, ris de veau aux truffes (sweetbreads with truffles), Waldorf salad, and Pêche Melba. Per anecdotal claims, among the restaurant's famously wealthy patrons was Charlie Chaplin, said to be among the world's highest-paid actors around that time. According to archaeologist Michael Shanks, the actor regarded it as his "favorite restaurant, on land or sea."

Despite the Prohibition's alcohol ban, wealthy Americans continued to drink in private clubs and speakeasies. Enterprising criminals established widespread illicit drinking venues — New York City alone was estimated to have anywhere between 20,000 and 100,000 — and served liquor to patrons who were able to pay premium prices. (Here's what really happened if you were caught drinking alcohol during Prohibition.)

Curiously, it seemed that eating healthy was a concern for both the rich and the not-so-rich. Dieting culture expanded during the era, shaping food choices toward "reducing" regimens (e.g., high-protein, low-carb, or no-sugar plans) and calorie-counting, even as celebratory meals remained indulgent.

What the filthy rich did for entertainment a century ago

With the swift and steady march of technology in the Roaring Twenties, the American public fell in love with novel forms of art and entertainment. During that decade, the average American could entertain themself by listening to contemporary music on the radio, dancing the Charleston or the Shimmy, or watching their favorite stars on the silent silver screen. (The first-ever 3D movie, a silent film released in the 1920s, is considered lost for good.)

But for the filthy rich, entertainment was on a different level and came in the form of restricted-membership leisure in exclusive settings. The social calendars of the 1920s elites included large private dances, charity balls, and country-club sports. The Jekyll Island Club in Georgia, which was popularly called a "millionaires' club," limited its membership to under 100 at a time and, by its own account, hosted families representing about one-sixth of the world's wealth. Member activities included hunting, golf, tennis, and related pastimes, with on-site facilities supporting those pursuits.

For the moneyed, not even the law could get in the way of a good time. In New York, the Cotton Club, opened in 1923 by gangster Owen "Owney" Madden, became a prominent, segregated cabaret for a wealthy clientele. Black performers headlined, while a white-only audience purchased drinks despite the federal ban. Interestingly, the Prohibition era shifted the affluent's alcohol consumption away from beer (which was perceived as low-class due to its pre-Prohibition associations with working-class saloons and German-American brewers) and toward distilled spirits and mixed drinks.

What the filthy rich wore in the Roaring Twenties

High-income Americans in the 1920s signaled status through couture and tailored apparel that aligned with leading trends of the decade. Womenswear favored simplified, tubular silhouettes with dropped waists alongside alternate robe de style forms. Evening garments commonly used silk with beadwork and sequins, while daywear increasingly incorporated sportswear elements, reflecting the influence of designers such as Coco Chanel and Jean Patou. The cloche hat, bobbed hairstyles, and rising hemlines peaked during this period, along with the acceptance of the little black dress (crepe de chine by day, chiffon by night). At the forefront of cutting-edge 1920s female fashion were the flappers, trendsetting young women whose fashion choices reflected their carefree attitudes (here's what it was really like being a 1920s flapper). For affluent women, premium fabrication (fine silks and high-grade wools), clothing expected to withstand regular wear, and seasonally appropriate sportswear were necessities to maintain their social status.

Meanwhile, menswear emphasized English tailoring and high-quality textiles — British wools, tweeds, and flannels — with casual suits, soft collars, and style innovations such as Oxford bags and plus-fours (trousers with an extra 4 inches of fabric) used for golf and daywear. Moreover, expensive outerwear quickly became a clear marker of wealth for young men, particularly at universities. Fur coats became conspicuous garments in high society and on elite campuses. Princeton newspapers said raccoon coats were all the rage, and Ivy League students spent hundreds of dollars to keep up with appearances.

The people who tended to the homes of the filthy rich

Domestic service for wealthy U.S. households in the 1920s was organized around live-in and live-out staff performing defined roles: maids, cooks, butlers, housekeepers, gardeners, chauffeurs, nursemaids, etc. These were supplemented by day workers for cleaning and laundry. During this decade, there was a marked shift toward day work with limited hours and hourly wages, as workers took advantage of the ginormous demand for laborers after the First World War. Some workers secured an eight-hour day and wages comparable to industrial employment, while live-in staff typically faced longer, less-defined hours. Moreover, this line of work was stratified by race and gender: At the beginning of the Roaring Twenties, four out of every 10 domestic workers in American households were African-American, the majority of whom were either laundresses or servants.

The family of wealthy shoe manufacturer Thomas Gustave Plant resided in Lucknow (aka Castle in the Clouds) in New Hampshire. While living there, they had in their employ "three servants in the house, a combination gardener and houseman, a combination chauffeur and stable man, and a man to care for what cows are necessary." The mansion itself contained four bedrooms for live-in servants, plus additional quarters on the grounds. Sadly, pay and protections left much to be desired: Allegedly, there was "no fixed rate or minimum wage" for domestic servants in the 1920s, with some even receiving only room and board as their compensation.

What the filthy rich drove in the 1920s

The urban, high-spending of the 1920s made luxury automobiles prominent status goods. These vehicles contrasted with mass-market cars as the U.S. auto industry expanded: Overall ownership and road mileage grew rapidly, yet the richest households concentrated spending on large, high-output luxury automobiles and gravitated to multi-cylinder engines that signaled expense and refinement. Formal "town car" coachwork was designed for city use, with an enclosed rear compartment and an exposed chauffeur's seat, highlighting the disparity between drivers and the elites they drove for. Inadvertently, this format also raised the total cost of automobiles beyond their base price.

Makers associated with upper-tier buyers included Rolls Royce, Packard, Pierce-Arrow, Cadillac, Mercedes, Maybach, and Duesenberg. Affluent buyers selected these brands for their combinations of bespoke bodies, improved performance, and service models accommodating a professional driver who often functioned as a mechanic. A popular example was Rolls Royce's "New Phantom" (later known as Phantom I), which was introduced in the mid-1920s and owned by the legendary dancer Fred Astaire.

Near the tail end of the 1920s, the Duesenberg Model J defined top-tier quality and exclusivity among American ultra-luxury cars. Aside from having state-of-the-art specifications that put it above its contemporary cars in terms of performance, there were fewer than 500 units manufactured between 1928 and 1935. Impressively, each Model J was a unique vehicle, as all of them were tailor-made according to the buyers' individual preferences.

How the filthy rich behaved in public during the Roaring Twenties

High-income Americans in the 1920s signaled their status in public through organized social rituals. Among the most iconic (and inescapable) of these were debutante balls. Much like how they were in England, debutante balls in the United States were significant affairs. Enjoying a resurgence in popularity following World War I, these formalized introductions of upper-class young women at balls and receptions were widely reported and photographed. Indeed, newspapers and magazines covered these events continuously; in a short satirical piece from December 1929, The New Yorker noted the repetitive visibility of debutantes in society pages: "Every day we see a picture of a débutante in the society pages, and although we used to imagine that the portrait changed from day to day, we now realize that it doesn't: it is the same girl."

The affluent's public displays of wealth and importance also extended to charity and arts patronage. A series of playful caricatures published by Vanity Fair in the early 20th century documented high-society social events, fund-raisers, and club life, showing the routinized settings in which these activities were performed while making sharp observations about the ultra-rich and their behavioral cliches. And while presented as being geared towards altruistic ends, philanthropy essentially cemented the status quo of the wealthy, mainly through foundations and named grants. In 1928, the Rockefeller Foundation committed to establishing the 40-ton, 200-inch Hale Telescope for Mount Palomar, an undertaking that reportedly cost $6,000,000 (over $109,000,000 in today's money) and took two decades to finish.

What the people of the 1920s thought of the filthy rich

Public reactions to the very wealthy in the Roaring Twenties were extensively documented in print, and they ranged from fascination with consumption to open criticism of their ostentatious behaviors. At the beginning of the decade, journalist Edwin Lefèvre published "The Annoyances of Being Rich Today" in The Saturday Evening Post, describing the wide variety of complaints — ranging from absurdly asinine to considerably classist — from the uber-wealthy Americans that he had opportunities to converse with. Barely hiding his disdain for these "wretchedly rich people," Lefèvre labeled such attitudes a form of "gold poisoning," producing "gold deafness" and "gold blindness."

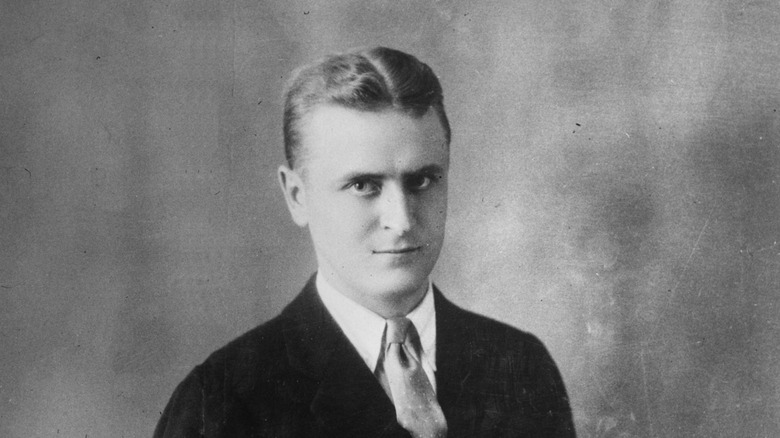

Most people today probably imagine the 1920s the way it was depicted in "The Great Gatsby." It has been said that in writing the novel, F. Scott Fitzgerald drew inspiration from his failed real-life relationship with socialite Ginevra King, which may explain his apparent love-hate relationship with the exorbitantly wealthy. Notably, he described the decade as "the most expensive orgy in history," a characterization that has mostly stuck with people who have read his work. His general opinion about the rich is best summed up in his 1926 short story, "The Rich Boy": "[The very rich] think, deep in their hearts, that they are better than we are because we had to discover the compensations and refuges of life for ourselves. Even when they enter deep into our world or sink below us, they still think that they are better than we are."

Not even the filthy rich were spared from the Great Depression

Eventually, the Roaring Twenties — and the outrageously lavish lifestyles of the filthy rich — came to a screeching halt with the 1929 crash of the stock market. This, combined with other financial and legal factors, marked the beginning of an economic collapse that affected even the highest-income households. Within the next four years, the U.S. real GDP fell by about 29%, thousands of banks found themselves in trouble, and the unemployment rate sharply rose. By March 1933, approximately 12.8 million Americans — about 25% of the civilian labor force — found themselves jobless.

Even multimillionaires felt the sting of the Great Depression. A notable example is steel executive Charles Michael Schwab, who had presided over major expansions at Bethlehem Steel. Schwab died in 1939, with his liabilities exceeding his assets. Two years later, Time Magazine ran an article that revealed how the late steelman had incurred over $2.2 million in debts in New York proceedings and additional debt in Pennsylvania filings. "Schwab had left no more to his heirs than if he had kept working at the $1-a-day job in which he entered the steel business in 1881," the report read.

With that said, while many fortunes contracted, some enterprises were founded or even expanded during this period of economic downturn. Such was the case of J.R. Simplot, who started growing potatoes on an Idaho farm in 1929. Eighty years later, approximately 33% of french fries in the United States came from the Simplots' potato empire.