Popular Things From The 1960s That Are Totally Banned Today

When today's older adults talk about "the good old days," it's more likely than not that they're talking about the 1960s, at least in part. That was when they were young and without a worry in the world, living in a decade that seemed ideal and idyllic. To be fair, there was a lot of objectively wonderful and solid stuff happening in the 1960s, especially with music, movies, and delicious hamburgers. As the decades wore on, the Baby Boomers who came of age during the '60s have endlessly looked back at that era with fondness, pushing their nostalgia onto later generations. Their fuzzy collective memories became firmly entrenched as fact, while all the negative, dangerous, and mind-boggling things from the 1960s were mostly forgotten. Fortunately for all, the wildest pastimes, procedures, and habits of the 1960s have been toned down or completely eradicated.

The 1960s were the tumultuous decade that housed the way worse than we thought Vietnam War and the brutally and nobly fought Civil Rights Movement; yet for many, the '60s were mainly about carefree living. It was a time when there was little regulation or seemingly little thought paid to the universal hazards in daily life. Here are some of the activities and behaviors that were extremely normal and commonplace, well-liked even, that just don't happen anymore, because it's basically illegal to engage in them in the 21st century.

Smoking on planes

Few parts of the 20th-century experience have been romanticized and waxed nostalgic over more than passenger flights of the 1960s. Fifty years ago, airline travel was objectively better in many ways than it is today, with full-service in-flight meals, flowing booze, and jumbo jets that could whisk a family from the East Coast of the U.S. to Europe in a handful of hours. This so-called golden age of air travel was also the golden age of smoking, and dark clouds set forth by a fully-loaded smoking section of the plane — yes, they were divided but not with any physical restriction — wafted throughout the cabin. Everyone breathed in all that second-hand smoke, and their clothes would reek by the time the plane landed. Flying was also a lot less safe and a lot louder than it is today, and plenty of passengers coped with the stress and fear by lighting up cigarette after cigarette.

The number of Americans who smoked declined in the 1970s and 1980s, with quitters urged to do so somewhat by the undeniable link between cigarettes and health problems like lung cancer. In 1990, in-flight smoking was banned on all domestic flights within the U.S., with supporters citing the need to protect the health of flight attendants and non-tobacco-using passengers.

Enjoying cigarette ads on TV

After the health risks associated with tobacco use, particularly by way of smoking cigarettes, became more conclusively proven and widely known, companies' legal ability to advertise tobacco products in the U.S. became increasingly difficult. Now, cigarette ads are primarily limited to magazines geared toward an adult readership. In the 1960s, cigarettes were advertised wherever advertising was accepted, and that included billboards and TV commercials that could air at any time of day, even or especially when children might be watching.

Television advertising of cigarettes ended on January 2, 1971, at the behest of a Congressional act in 1970. The tobacco industry and broadcasters were extremely opposed to the prohibition because, in the 1960s, cigarette advertising injected $200 million into TV. At the time, 11% of all commercials were for cigarettes. Fully produced ads, as well as in-character, studio-shot sponsor spots, littered TV throughout the decade. Winston even enlisted the services of beloved '60s cartoon characters Fred Flintstone and Barney Rubble to endorse their product in one minute-long televised ad.

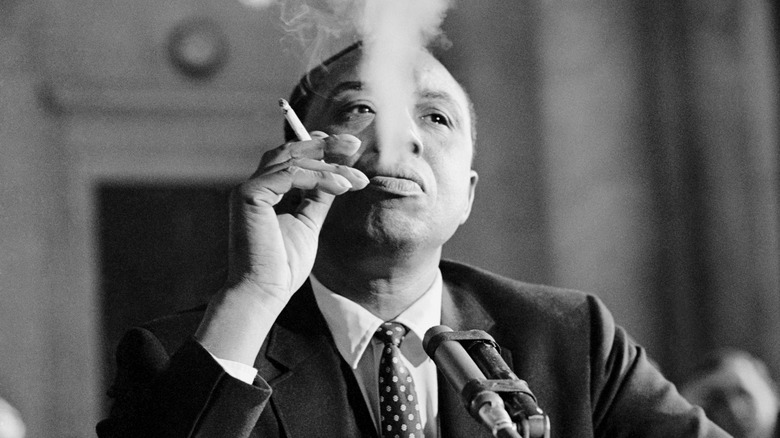

Smoking anywhere and everywhere

Working outside the home and driving a giant car that ran on toxic gasoline were normal, expected behaviors of American adults in the 1960s. Another practice that was so common as to be mundane among grown-ups of the era was smoking. In 1965, 42% of American adults identified as smokers, according to the American Lung Association. Of that demographic, the most likely smokers were men (52%) and adults between the ages of 25 and 44 (51%). That's the highest percentage of smokers in the United States since the American Lung Association began keeping records, with the figure falling consistently ever since. In the 2020s, only 11.6% of American adults regularly smoke cigarettes.

In the 1960s, cigarettes were the most popular nicotine delivery method, and since so many millions of people smoked them throughout the day and every day, concessions were made to that segment. It was common practice for restaurants and bars to have a smoking section and a non-smoking section (before many such establishments started to ban tobacco use on the premises entirely in the late '90s and early 2000s). Gift shops in hospitals, where people might be being treated for advanced lung diseases caused by smoking, sold cigarettes. Medical complexes even had dedicated rooms for smokers if they didn't also allow patients to smoke from their beds and nurses to smoke while on duty. Smoking lounges in public places, including schools, stuck around through the latter half of the 20th century.

Eating dangerous foods

Many processed meals and snacks that hit the scene in the '60s were colored with artificial dyes that made them more vibrant than foods existing in nature could ever be. One of the most widely used was Red Dye No. 2, synthesized from petroleum and cheaper than plant-derived dyes.

In the 1960s, Red Dye No. 2 was an ingredient in $4 million worth of food sold in the U.S. each year, primarily soft drinks, artificial juices, candy, cereals, maraschino cherries, alcoholic drinks, ice cream, and various shelf-stable powdered foods. Used since the late 19th century, the public took notice of the potentially dangerous food dye in 1960, when Congress revised the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 to ban edible chemicals with a demonstrated connection to cancer. After a 1969 study by the Moscow Institute of Nutrition resulted in lab rats that ate Red Dye No. 2 developing tumors, the drive to ban the substance began in earnest. It was outlawed in 1976.

Another possibly dangerous food that was eaten a lot more in the 1960s than it is today is haggis. The traditional Scottish dish is made from ground-up organ meat and spices stuffed into a sheep's stomach and then boiled and served. Scottish-American communities in the U.S. suffered a culinary loss when the federal government banned the eating of the lungs of livestock in 1971 for safety reasons. The decision effectively prohibited the manufacture and sale of authentic haggis nationwide.

Using leaded gas

Back in the 1920s, leaded gasoline went on sale at the many automobile service stations across the United States. General Motors engineers discovered that the chemical additive TEL, or tetraethyl lead, increased the quality or octane of gasoline because it prevented a massively engine-damaging reaction called knocking. The vast majority of gasoline used throughout the U.S. into the 1960s and a little bit beyond was leaded. It remained the standard, despite the well-known and severe effects of exposure to the substance, such as damage to the immune, cardiovascular, and nervous systems, and causing psychological and neurological problems in children. Yet Americans loved driving, and as car culture thrived in the 1950s and 1960s, vehicle owners and operators continued filling their tanks with leaded gas because it kept their domestically-built, powerful, gas-guzzling muscle cars humming.

While less popular alternatives, like ethanol, were available, the leaded gas phase-out from consumer-level automobiles didn't happen until 1975. Congress passed the Clean Air Act of 1970, which required cars to meet stricter emissions standards. Leaded gas polluted the air with lead and other particles, and unleaded gas didn't, particularly when it was used in cars with catalytic converters. It wasn't outlawed in road vehicles until 1996, and later studies showed just how horrific an effect it imposed. A 2022 research report estimated that Americans who grew up in the leaded gas era collectively lost 824 million IQ points.

Riding in cars unsecured

Seatbelts in cars existed well before the 1960s; they were just extremely unpopular. In the U.S., the first prototype was patented in 1885, and in 1953, the Colorado State Medical Society advocated for pushing American automobile manufacturers to make lap belts a standard feature. California mandated them from 1955 on, but across the country, the seat belts that had actually made it into cars were seldom used — about 1% of drivers and passengers buckled up before a federal law made installation required. It wasn't until 1974 that the government started to force car makers to utilize three-point seatbelts, far safer than the previous, simple lap belt design, which could contribute to spinal injuries when worn during serious accidents.

Between 1977 and 1985, laws designed to keep children and babies secure in vehicles through the use of an automotive restraint device went into effect in every state. However, throughout the 1960s, kids and adults alike rode in cars like they were sitting on chairs or couches at home. Back then, being able to move about the vehicle or hang out in the back of pick-up trucks or the far-rear area of station wagons wasn't out of the ordinary.

Corporal punishment for children

Let's call corporal punishment what it is: legally and socially sanctioned violence doled out as discipline for intolerable behavior. It was prevalent and acceptable in the 1960s for parents to strike their children, often on the rear end and with varying levels of force, as a punishment for any number of offenses. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, less than 35% of present-day parents say they've spanked a child. Parents of the Millennial and Generation X persuasion are far less likely to spank their children than parents from older generations. "As we've woken up to the issues of domestic violence and intimate partner violence, there's been a growing rejection of any sort of violence within the home, including spanking," Dr. Robert Sege of the American Academy of Pediatrics said in a statement (via CNN).

At home, misbehaving '60s kids faced the wrath of mom or dad. At school, teachers and administrators could use violence to punish, too, most famously with a large wooden paddle used in the act of spanking. In 1977, the Supreme Court ruled paddling in schools to be alright on the grounds that it wasn't excessively mean. Changing attitudes, and the idea that it wasn't the most effective consequence or deterrent, led to 30 states banning paddling in school between 1974 and the mid-'90s.

Playing with Clackers

Clackers were never among the biggest Christmas toy crazes in history, but they sold well and consistently throughout the late 1960s. Despite being one of the most dangerous toys ever sold to the public, Clackers, also known as knockers, click-clacks, and other onomatopoeia-employing names, were a decidedly low-tech plaything. The toy consists of two small, very hard balls suspended on a string with a plastic or metal loop in the middle. The object was to swing the clacker around until the balls crashed into each other with a loud, cracking noise. Clackers were sort of the mid-20th-century version of the 21st-century phenomenon, fidget spinners.

It sure was fun to move those balls around, as fun as it was hazardous. These spheres, which were essentially projectiles, flew around with such unpredictability that kids maimed themselves and others, either accidentally or on purpose. Clacker balls also had a tendency to break up upon impact, sending shards of sharp plastic every which way. The FDA warned the public about using clackers in 1971, after receiving reports of four injuries. They were ultimately banned in many jurisdictions, although the short-lived nature of fads probably also played a hand in ending the great clacker menace.

Drinking water and not thinking about it

In 2024, purified bottled water is a $112 billion industry. It took a while for water companies to convince Americans to pay money for something that cost almost nothing out of the kitchen faucet. The commercialization process began when France debuted bottles of mineral water in the late 1960s. Before then, if someone wanted a glass of water (or rather needed one; it's vital for sustaining life), they'd go to a faucet, consult a well, or take a deep gulp from a garden hose if they were outside and it was especially hot.

Americans of the 1960s lived in blissful ignorance about the state of their water. Both the tap and bottled versions in contemporary times are significantly cleaner than the water of the 1960s. Inexpensive and accessible filtration units mean that 77% of homes today filter their drinking water, even though the Environmental Protection Agency monitors and restricts 90 contaminating substances in the supply. Water standards passed in 1962 looked for only 28 contaminants. Before the Clean Water Act was passed in 1972, it was a lot easier (and a lot more legal) for industrial operations to dispense massive amounts of sewage and waste directly into freshwater sources.

Driving really fast

In the wake of a 1970s Middle Eastern oil embargo imposed by Arab countries as retaliation for the United States' support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War, Americans faced gas shortages. Based on the theory that driving faster uses up more gas, President Richard Nixon signed into law the Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act in January 1974. It established a national speed limit of 55 miles per hour and marked the end of an era — one in which Americans could drive really fast in a lot of places.

Back in the 1960s, it was up to states to determine the speed limit on their highways and surface roads. That number could run as high as 80 mph in some places — a big difference from the 55 mph that would be legally imposed a few years later. On country roads and in rural areas, where traffic congestion wasn't a problem and police seldom monitored, drivers weren't given any posted limit. They were trusted to travel at a speed that seemed reasonable to them at the time. This antiquated practice laid the groundwork for what became known as the 85% rule.

Freely using pesticides

Flying insects can carry and rapidly spread horrific diseases like typhus and malaria, as well as destroy valuable crops. DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane ) could efficiently kill such dangerous pests. Widespread use of this chemical insecticide in the U.S. began in the late 1940s, and it was hailed as a transformative marvel of science. DDT usage reached its height in 1959, when 80 million pounds of it were dispensed in a single year. It continued to be heavily utilized in American agriculture throughout the 1960s. Over its lifespan of availability, 675,000 tons of DDT were applied to plants across the U.S.

The decline of DDT began in 1962, with the publication of Rachel Carson's "Silent Spring," an exposé detailing the little-known and covered-up long-term side effects of DDT on the environment, humans, and animals. After the Environmental Protection Agency was established in 1970, it took two more years to ban DDT in the U.S.

Making use of mercury

Mercury is a heavy metal and chemical element known as quicksilver. It takes the form of a liquid when at room temperature, and has many industrial and household uses. Mercury is one of the most accurate temperature-gauging tools, and well into the 1960s, it was the key ingredient in home thermometers. Liquid mercury embedded in a thin tube of glass would rise and fall when placed under the tongue of a sick kid with a fever. One of the big problems with those thermometers, however, was that they broke easily, and the liquid metal leaked out. Exposure to mercury can cause mercury poisoning, which carries symptoms like difficulty breathing, coughing, and vomiting.

Another potential source of mercury poisoning to mid-century kids: toys. Fisher-Price used the stuff in the manufacture of many of its toys, including its Little People figures and play sets. Mercury was slowly phased out of common products, including thermometers and toys, but it took a long time. It wasn't until the early 2000s that states started outright banning its use.